Weird and Wonderful: The psychedelic jelly is one of the most colorful residents of the deep sea

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Thursday, January 06, 2022

Study reveals more hostile conditions on Earth as life evolved

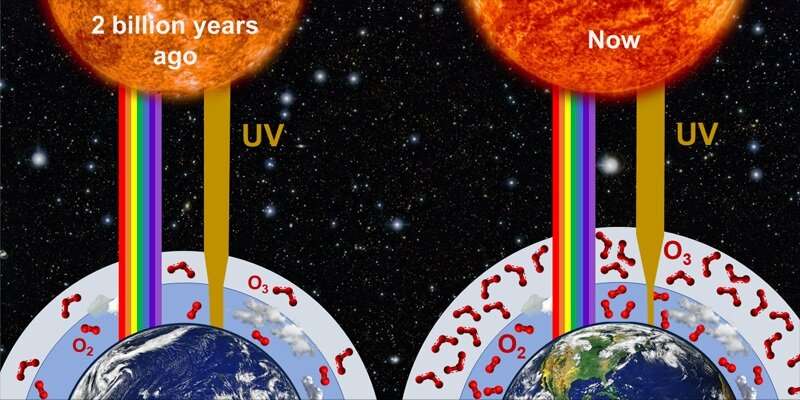

During long portions of the past 2.4 billion years, the Earth may have been more inhospitable to life than scientists previously thought, according to new computer simulations.

Using a state-of-the-art climate model, researchers now believe the level of ultraviolet (UV) radiation reaching the Earth's surface could have been underestimated, with UV levels being up to ten times higher.

UV radiation is emitted by the sun and can damage and destroy biologically important molecules such as proteins.

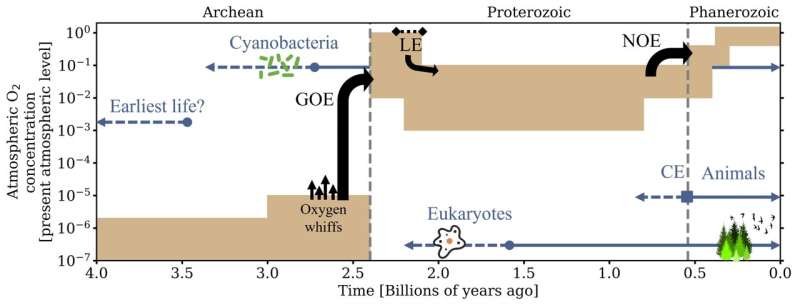

The last 2.4 billion years represents an important chapter in the development of the biosphere. Oxygen levels rose from almost zero to significant amounts in the atmosphere, with concentrations fluctuating but eventually reaching modern day concentrations approximately 400 million years ago.

During this time, more complex multicellular organisms and animals began to colonize land.

Gregory Cooke, a Ph.D. researcher at the University of Leeds who led the study, said the findings raise new questions about the evolutionary impact of UV radiation as many forms of life are known to be negatively affected by intense doses of UV radiation.

He said: "We know that UV radiation can have disastrous effects if life is exposed to too much. For example, it can cause skin cancer in humans. Some organisms have effective defense mechanisms, and many can repair some of the damage UV radiation causes.

"Whilst elevated amounts of UV radiation would not prevent life's emergence or evolution, it could have acted as a selection pressure, with organisms better able to cope with greater amounts of UV radiation receiving an advantage."

The research "A revised lower estimate of ozone columns during Earth's oxygenated history" is published today in the scientific journal Royal Society Open Science.

The amount of UV radiation reaching the Earth is limited by the ozone in the atmosphere, described by the researchers as "...one of the most important molecules for life" because of its role in absorbing UV radiation as it passes into the Earth's atmosphere.

Ozone forms as a result of sunlight and chemical reactions—and its concentration is dependent on the level of oxygen in the atmosphere.

For the last 40 years, scientists have believed that the ozone layer was able to shield life from harmful UV radiation when the level of oxygen in the atmosphere reached about one percent relative to the present atmospheric level.

The new modeling challenges that assumption. It suggests the level of oxygen needed may have been much higher, perhaps 5% to 10% of present atmospheric levels.

As a result, there were periods when UV radiation levels at the Earth's surface were much greater, and this could have been the case for most of the Earth's history.

Mr Cooke said: "If our modeling is indicative of atmospheric scenarios during Earth's oxygenated history, then for over a billion years the Earth could have been bathed in UV radiation that was much more intense than previously believed.

"This may have had fascinating consequences for life's evolution. It is not precisely known when animals emerged, or what conditions they encountered in the oceans or on land. However, depending on oxygen concentrations, animals and plants could have faced much harsher conditions than today's world. We hope that the full evolutionary impact of our results can be explored in the future."

The results will also lead to new predictions for exoplanet atmospheres. Exoplanets are planets that orbit other stars. The presence of certain gases, including oxygen and ozone, may indicate the possibility of extra-terrestrial life, and the results of this study will aid in the scientific understanding of surface conditions on other worldsOzone pollution has increased in Antarctica

More information: A revised lower estimate of ozone columns during Earth's oxygenated history, Royal Society Open Science (2022). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.211165. royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.211165

Journal information: Royal Society Open Science

Provided by University of Leeds

Will Hydrogen Finally Live Up To The Hype?

By Tsvetana Paraskova - Jan 04, 2022,- Hydrogen stocks retreated in 2021 after posting tremendous gains in 2020

- The number of green hydrogen projects soared in 2021

- Closer public-private collaboration is critical to increasing investments

Low-carbon hydrogen could play a crucial role in the decarbonization of energy-intensive industries and in helping nations to reduce emissions and move closer to their net-zero emission targets, analysts and forecasting agencies say. The number of announced green hydrogen projects—those looking to produce hydrogen from water electrolysis using renewable energy—has soared over the past year, doubling from the number of projects announced in 2020.

Renewable hydrogen, however, still faces a steep learning curve for significant cost reductions as well as roadblocks on the path to becoming a competitive large-scale alternative to grey hydrogen, made from fossil fuels, or blue hydrogen produced from natural gas using carbon capture.

Hydrogen Stocks Cool

Investors have seemed to realize that the bright future for green hydrogen still depends on achieving significant cost reductions and becoming a competitive energy source. Shares in electrolyzer hydrogen-producing companies retreated in 2021, following a blistering rally in the previous year, according to FactSet data compiled by The Wall Street Journal.

The market seems to have realized that green hydrogen still has a long way to go to become a competitive large-scale alternative to traditional fuels and storage solutions, and still depends on government incentives and initiatives for deployment, demand creation, and cost reductions, the Journal’s Rochelle Toplensky notes.

But Green Hydrogen Projects Gather Momentum

While the stock performance of low-cost hydrogen makers in 2021 has started to reflect the Street’s recalibrated view that it could take green hydrogen up to a decade to become cost-competitive, green hydrogen projects are being announced at the fastest pace ever seen.

More than 520 projects were announced in 2021, up by 100 percent compared to 2020, according to a November 2021 report by the Hydrogen Council, a global CEO-led initiative. As many as 221 of those projects are for large-scale industrial usage, 133 in the transport sector, 74 in the integrated hydrogen economy, 51 are infrastructure projects, and 43 are giga-scale production projects, the Council said in its ‘Hydrogen for Net-Zero’ report.

Related: OPEC+ Continues To Struggle To Produce As Much As Quotas Allow

According to the Hydrogen Council, the fuel is central to reaching net-zero emissions because it can abate 80 gigatons of CO2 by 2050 and is critical in enabling a decarbonized energy system.

Clean Hydrogen Needs More Investment, Policy Support

However, scaling will also be critical this decade, as will be investments because half a trillion U.S. dollars in additional investment is still needed in net-zero scenarios.

Closer public-private collaboration is critical to increasing investments because a fourfold increase is required by 2030 to put the world on the trajectory to Net Zero, the Council says.

“There is clear momentum in hydrogen investments, but a transformation of such magnitude requires unprecedented mobilisation of public and private resources through strong partnerships and policy support,” said Tom Linebarger, Chairman and CEO of Cummins and Co-Chair of the Hydrogen Council, commenting on the report.

Clean hydrogen needs more pledges and investments in order to see cost reductions and usage in various industries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its Global Hydrogen Review 2021 in October.

“Governments need to move faster and more decisively on a wide range of policy measures to enable low-carbon hydrogen to fulfill its potential to help the world reach net zero emissions while supporting energy security,” the IEA said.

“We have experienced false starts before with hydrogen, so we can’t take success for granted. But this time, we are seeing exciting progress in making hydrogen cleaner, more affordable and more available for use across different sectors of the economy,” said Fatih Birol, the IEA Executive Director.

Government and private investment in hydrogen are still way below the capital necessary to put the sector on track for net-zero by 2050, the agency says. Countries have committed at least $37 billion, and the private sector has announced $300 billion in investment. Yet, net-zero by 2050 requires $1.2 trillion of investment in low-carbon hydrogen supply and use through to 2030, the IEA notes.

When Will Green Hydrogen Become Cost Competitive?

According to the agency, low-carbon hydrogen can become competitive within the next decade.

Green hydrogen can be competitive in some major markets by 2030, with Brazil and Chile front-runners, Bridget van Dorsten, Hydrogen Research Analyst at Wood Mackenzie, said last month.

Currently, green hydrogen has a small share of the global energy market and is still largely uncompetitive against fossil-fuelled alternatives, van Dorsten says.

Electrolyzer capex is expected to significantly decline by 2025, due to a range of factors, including economies of scale, new entrants to the market, greater automation, and increased modularity, according to Wood Mackenzie.

The real game-changer for hydrogen will come when low-carbon green hydrogen costs become competitive in major markets, WoodMac reckons.

“However, the momentum behind net zero ambitions means that investors are betting on its long-term potential,” van Dorsten noted.

Renewable hydrogen has the chance to become an alternative game-changer fuel for the global energy market, but it has to overcome several barriers before that, including high input costs and dependence on government policies.

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com

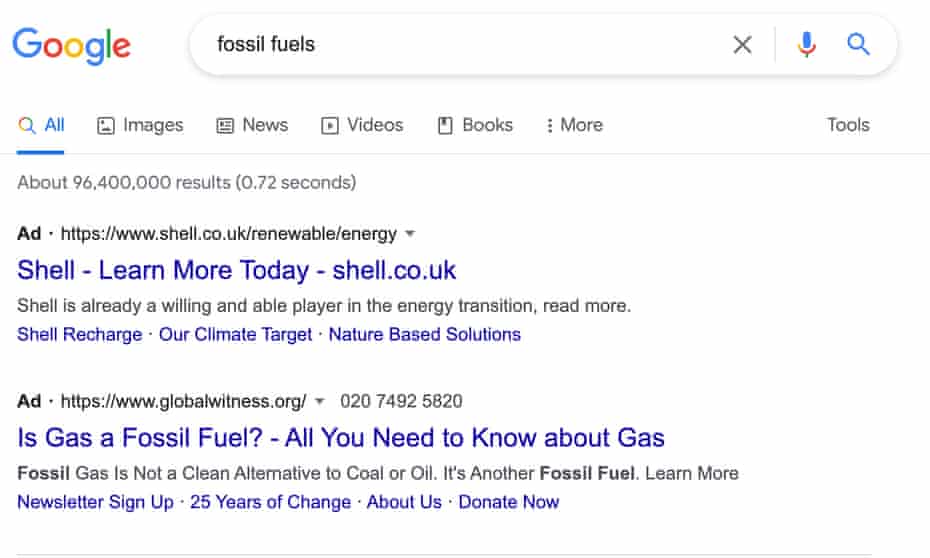

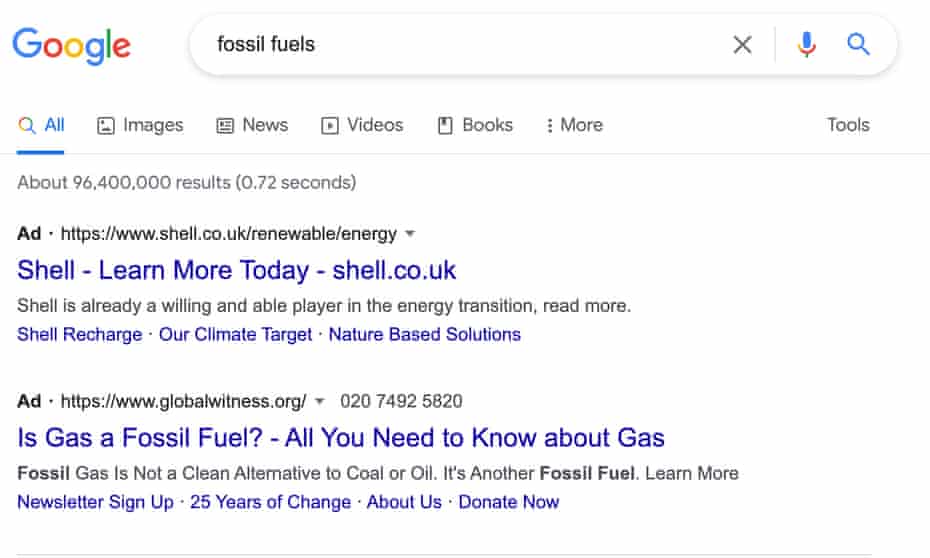

Fossil fuel firms among biggest spenders on Google ads that look like search results

One in five ads served on search results for 78 climate-related terms placed by firms with interests in fossil fuels, research finds

One in five ads served on search results for 78 climate-related terms placed by firms with interests in fossil fuels, research finds

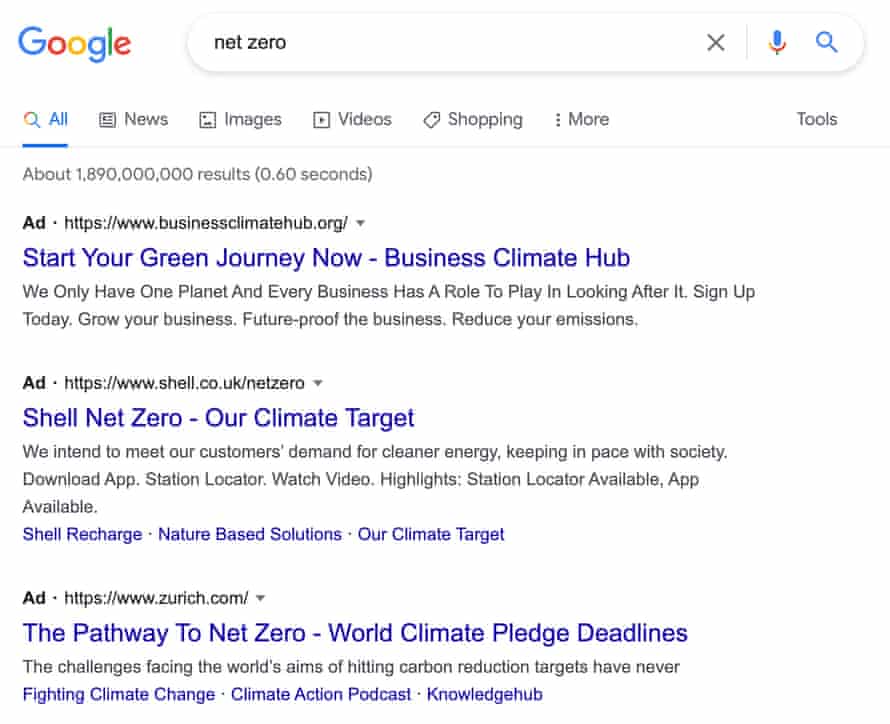

Google ads on the search term ‘fossil fuels’ Photograph: Google

Niamh McIntyre

@niamh_mcintyre

Wed 5 Jan 2022

Fossil fuel companies and firms that work closely with them are among the biggest spenders on ads designed to look like Google search results, in what campaigners say is an example of “endemic greenwashing”.

The Guardian analysed ads served on Google search results for 78 climate-related terms, in collaboration with InfluenceMap, a thinktank that tracks the lobbying efforts of polluting industries.

The results show that over one in five ads seen in the study – more than 1,600 in total – were placed by companies with significant interests in fossil fuels.

Advertisers pay for their ads to appear on the search engine when a user queries certain terms. The ads are appealing to businesses because they are very similar in appearance to search results: more than half of users in a 2020 survey reported they could not tell the difference between a paid-for listing and a normal Google result.

ExxonMobil, Shell, Aramco, McKinsey, and Goldman Sachs were among the top-20 advertisers on the search terms, while a number of other fossil fuel producers and their financiers also placed ads.

Jake Carbone, senior data analyst at InfluenceMap, said: “Google is letting groups with a vested interest in the continued use of fossil fuels pay to influence the resources people receive when they are trying to educate themselves.

“The oil and gas sector has moved away from contesting the science of climate change and now instead seeks to influence public discussions about decarbonisation in its favour.”

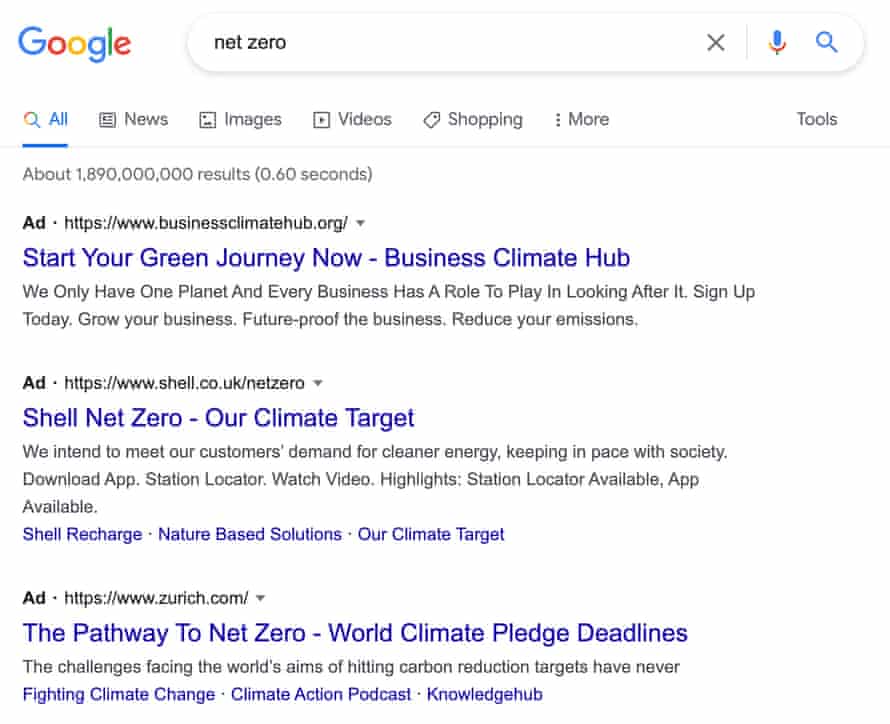

Oil major Shell’s ads – 153 were counted in total – appeared on 86% of searches for “net zero”. Many promoted its pledge to become a net zero company by 2050 and align itself with a 1.5C warming target.

Niamh McIntyre

@niamh_mcintyre

Wed 5 Jan 2022

Fossil fuel companies and firms that work closely with them are among the biggest spenders on ads designed to look like Google search results, in what campaigners say is an example of “endemic greenwashing”.

The Guardian analysed ads served on Google search results for 78 climate-related terms, in collaboration with InfluenceMap, a thinktank that tracks the lobbying efforts of polluting industries.

The results show that over one in five ads seen in the study – more than 1,600 in total – were placed by companies with significant interests in fossil fuels.

Advertisers pay for their ads to appear on the search engine when a user queries certain terms. The ads are appealing to businesses because they are very similar in appearance to search results: more than half of users in a 2020 survey reported they could not tell the difference between a paid-for listing and a normal Google result.

ExxonMobil, Shell, Aramco, McKinsey, and Goldman Sachs were among the top-20 advertisers on the search terms, while a number of other fossil fuel producers and their financiers also placed ads.

Jake Carbone, senior data analyst at InfluenceMap, said: “Google is letting groups with a vested interest in the continued use of fossil fuels pay to influence the resources people receive when they are trying to educate themselves.

“The oil and gas sector has moved away from contesting the science of climate change and now instead seeks to influence public discussions about decarbonisation in its favour.”

Oil major Shell’s ads – 153 were counted in total – appeared on 86% of searches for “net zero”. Many promoted its pledge to become a net zero company by 2050 and align itself with a 1.5C warming target.

Google ads on the search term ‘net zero’. Photograph: Google

However, Shell’s net-zero strategy relies heavily on carbon capture and offsetting, according to a Carbon Brief analysis, which says: “Despite its ‘highly ambitious’ framing … Shell’s vision of a continued role for oil, gas and coal until the end of the century remains essentially the same.”

A spokesperson for Shell said: “Shell’s target is to become a net zero emissions energy business by 2050, in step with society. Our short, medium and long-term intensity and absolute targets are consistent with the more ambitious 1.5C goal of the Paris agreement.”

Goldman Sachs, which facilitated nearly $19bn of lending to the fossil fuel industry in 2020, had the third highest number of ads. The bank’s ads appeared on almost six in 10 searches for “renewable energy”, with many emphasising its “continued commitment to sustainable finance”.

Consulting firm McKinsey’s ads appeared on more than eight in 10 searches for “energy transition” and four in 10 searches for “climate hazards”. Its ads stated: “McKinsey works with clients on innovation & growth that advances sustainability.”

Alongside its work on sustainable investing, the company receives significant income from fossil fuel clients. In recent years McKinsey has advised 43 out of the world’s 100 most polluting companies, according to the New York Times.

A spokesperson for McKinsey pointed to an op-ed written by a managing partner at the company, which states: “There is no way to deliver emissions reductions without working with these industries to rapidly transition.”

Aramco, the state-owned Saudi oil company, which is the world’s largest oil exporter, had 114 ads on the keywords “carbon storage”, “carbon capture” and “energy transition”. A number of their ads claimed the company “promoted biodiversity” and “protected the planet”.

However, Shell’s net-zero strategy relies heavily on carbon capture and offsetting, according to a Carbon Brief analysis, which says: “Despite its ‘highly ambitious’ framing … Shell’s vision of a continued role for oil, gas and coal until the end of the century remains essentially the same.”

A spokesperson for Shell said: “Shell’s target is to become a net zero emissions energy business by 2050, in step with society. Our short, medium and long-term intensity and absolute targets are consistent with the more ambitious 1.5C goal of the Paris agreement.”

Goldman Sachs, which facilitated nearly $19bn of lending to the fossil fuel industry in 2020, had the third highest number of ads. The bank’s ads appeared on almost six in 10 searches for “renewable energy”, with many emphasising its “continued commitment to sustainable finance”.

Consulting firm McKinsey’s ads appeared on more than eight in 10 searches for “energy transition” and four in 10 searches for “climate hazards”. Its ads stated: “McKinsey works with clients on innovation & growth that advances sustainability.”

Alongside its work on sustainable investing, the company receives significant income from fossil fuel clients. In recent years McKinsey has advised 43 out of the world’s 100 most polluting companies, according to the New York Times.

A spokesperson for McKinsey pointed to an op-ed written by a managing partner at the company, which states: “There is no way to deliver emissions reductions without working with these industries to rapidly transition.”

Aramco, the state-owned Saudi oil company, which is the world’s largest oil exporter, had 114 ads on the keywords “carbon storage”, “carbon capture” and “energy transition”. A number of their ads claimed the company “promoted biodiversity” and “protected the planet”.

Orion’s fireplace: ESO releases new image of the Flame Nebula

4 January 2022

Orion offers you a spectacular firework display to celebrate the holiday season and the new year in this new image from the European Southern Observatory (ESO). But no need to worry, this iconic constellation is neither exploding nor burning. The “fire” you see in this holiday postcard is Orion’s Flame Nebula and its surroundings captured in radio waves — an image that undoubtedly does justice to the nebula’s name! It was taken with the ESO-operated Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX), located on the cold Chajnantor Plateau in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

The newly processed image of the Flame Nebula, in which smaller nebulae like the Horsehead Nebula also make an appearance, is based on observations conducted by former ESO astronomer Thomas Stanke and his team a few years ago. Excited to try out the then recently installed SuperCam instrument at APEX, they pointed it towards the constellation Orion. “As astronomers like to say, whenever there is a new telescope or instrument around, observe Orion: there will always be something new and interesting to discover!” says Stanke. A few years and many observations later, Stanke and his team have now had their results accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

One of the most famous regions in the sky, Orion is home to the giant molecular clouds closest to the Sun — vast cosmic objects made up mainly of hydrogen, where new stars and planets form. These clouds are located between 1300 and 1600 light-years away and feature the most active stellar nursery in the Solar System’s neighbourhood, as well as the Flame Nebula depicted in this image. This “emission” nebula harbours a cluster of young stars at its centre that emit high-energy radiation, making the surrounding gases shine.

With such an exciting target, the team were unlikely to be disappointed. In addition to the Flame Nebula and its surroundings, Stanke and his collaborators were able to admire a wide range of other spectacular objects. Some examples include the reflection nebulae Messier 78 and NGC 2071 — clouds of interstellar gas and dust believed to reflect the light of nearby stars. The team even discovered one new nebula, a small object, remarkable in its almost perfectly circular appearance, which they named the Cow Nebula.

The observations were conducted as part of the APEX Large CO Heterodyne Orion Legacy Survey (ALCOHOLS), which looked at the radio waves emitted by carbon monoxide (CO) in the Orion clouds. Using this molecule to probe wide areas of the sky is the primary goal of SuperCam, as it allows astronomers to map large gas clouds that give birth to new stars. Unlike what the “fire” of this image might suggest, these clouds are actually cold, with temperatures typically just a few tens of degrees above absolute zero.

Given the many secrets it can tell, this region of the sky has been scanned many times in the past at different wavelengths, each wavelength range unveiling different, unique features of Orion’s molecular clouds. One example are the infrared observations performed with ESO’s Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile that make up the peaceful background of this image of the Flame Nebula and its surroundings. Unlike visible light, infrared waves pass through the thick clouds of interstellar dust, allowing astronomers to spot stars and other objects which would otherwise remain hidden.

So, this holiday season, bring in the new year with this spectacular multiwavelength firework show put on by the Orion’s Flame Nebula, presented by ESO!

More information

The observations mentioned in this press release are presented in a paper accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The team is composed of Th. Stanke (European Southern Observatory, Garching bei München, Germany [ESO]), H. G. Arce (Department of Astronomy, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA), J. Bally (CASA, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA), P. Bergman (Department of Space, Earth and Environment, Chalmers University of Technology, Onsala Space Observatory, Onsala, Sweden), J. Carpenter (Joint ALMA Observatory, Santiago, Chile [ALMA]), C. J. Davis (National Science Foundation, Alexandria, VA, USA), W. Dent (ALMA), J. Di Francesco (NRC Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics, Victoria, BC, Canada [HAA] and Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Victoria, BC, Canada [UVic]), J. Eislöffel (Thüringer Landessternwarte, Tautenburg, Germany), D. Froebrich (School of Physical Sciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK), A. Ginsburg (Department of Astronomy, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA), M. Heyer (Department of Astronomy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA), D. Johnstone (HAA and UVic), D. Mardones (Departamento de Astronomía, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile), M. J. McCaughrean (European Space Agency, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands), S. T. Megeath (Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Toledo, OH, USA), F. Nakamura (National Astronomical Observatory, Tokyo, Japan), M. D. Smith (Centre for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, School of Physical Sciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK), A. Stutz (Departmento de Astronomía, Facultad de Ciencias Físicas y Matemáticas, Universidad de Concepción, Chile), K. Tatematsu (Nobeyama Radio Observatory, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, National Institutes of Natural Sciences, Nagano, Japan), C. Walker (Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, US [SO]), J. P. Williams (Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, HI, USA), H. Zinnecker (Universidad Autonoma de Chile, Santiago, Chile), B. J. Swift (SO), C. Kulesa (SO), B. Peters (SO), B. Duffy (SO), J. Kloosterman (University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, IN, USA), U. A. Yıldız (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA [JPL]), J. L. Pineda (JPL), C. De Breuck (ESO), and Th. Klein (European Southern Observatory, Santiago, Chile).

APEX is a collaboration between the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR), the Onsala Space Observatory (OSO) and ESO. Operation of APEX at Chajnantor is entrusted to ESO.

SuperCAM is a project by the Steward Observatory Radio Astronomy Laboratory at the University of Arizona, US.

The European Southern Observatory (ESO) enables scientists worldwide to discover the secrets of the Universe for the benefit of all. We design, build and operate world-class observatories on the ground — which astronomers use to tackle exciting questions and spread the fascination of astronomy — and promote international collaboration in astronomy. Established as an intergovernmental organisation in 1962, today ESO is supported by 16 Member States (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), along with the host state of Chile and with Australia as a Strategic Partner. ESO’s headquarters and its visitor centre and planetarium, the ESO Supernova, are located close to Munich in Germany, while the Chilean Atacama Desert, a marvellous place with unique conditions to observe the sky, hosts our telescopes. ESO operates three observing sites: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope and its Very Large Telescope Interferometer, as well as two survey telescopes, VISTA working in the infrared and the visible-light VLT Survey Telescope. Also at Paranal ESO will host and operate the Cherenkov Telescope Array South, the world’s largest and most sensitive gamma-ray observatory. Together with international partners, ESO operates APEX and ALMA on Chajnantor, two facilities that observe the skies in the millimetre and submillimetre range. At Cerro Armazones, near Paranal, we are building “the world’s biggest eye on the sky” — ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope. From our offices in Santiago, Chile we support our operations in the country and engage with Chilean partners and society.

Links

bout the Release

Release No.: eso2201 Name: Flame Nebula Type: Milky Way : Nebula : Appearance : Emission Facility: Atacama Pathfinder Experiment Instruments: SuperCam

| Release No.: | eso2201 |

| Name: | Flame Nebula |

| Type: | Milky Way : Nebula : Appearance : Emission |

| Facility: | Atacama Pathfinder Experiment |

| Instruments: | SuperCam |

Images

Videos

Detailed Footage Finally Reveals What Triggers Lightning

Scientists have never been able to adequately explain where lightning comes from. Now the first detailed observations of its emergence inside a cloud have exposed how electric fields grow strong enough to let bolts fly.

In this animation of a lightning flash recorded by the LOFAR radio telescope network, each dot is the location of a radio source. The flash, which is 5 kilometers wide, grew out of a small region of the cloud measuring tens of meters across.

Brian Hare

Thomas Lewton

Contributing Writer

December 20, 2021

During a summer storm in 2018, a momentous lightning bolt flashed above a network of radio telescopes in the Netherlands. The telescopes’ detailed recordings, which were processed only recently, reveal something no one has seen before: lightning actually starting up inside a thundercloud.

In a new paper that will soon be published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers used the observations to settle a long-standing debate about what triggers lightning — the first step in the mysterious process by which bolts arise, grow and propagate to the ground. “It’s kind of embarrassing. It’s the most energetic process on the planet, we have religions centered around this thing, and we have no idea how it works,” said Brian Hare, a lightning researcher at the University of Groningen and a co-author of the new paper.

The schoolbook picture is that, inside a thundercloud, hail falls as lighter ice crystals rise. The hail rubs off the ice crystals’ negatively charged electrons, leading the top of the cloud to become positively charged while the bottom becomes negatively charged. This creates an electric field that grows until a gigantic spark jumps across the sky.

Yet the electric fields inside clouds are about 10 times too weak to create sparks. “People have been sending balloons, rockets and airplanes into thunderstorms for decades and never seen electric fields anywhere near large enough,” said Joseph Dwyer, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire and a co-author on the new paper who has puzzled over the origins of lightning for over two decades. “It’s been a real mystery how this gets going.”

A big impediment is that clouds are opaque; even the best cameras can’t peek inside to see the moment of initiation. Until recently, this left scientists little choice but to venture into the storm — something they’ve been trying since Benjamin Franklin’s famous kite experiment of 1752. (According to a contemporaneous account, Franklin attached a key to a kite and flew it beneath a thundercloud, observing that the kite became electrified.) More recently, weather balloons and rockets have offered snapshots of the interior, but their presence tends to interfere with the data by artificially creating sparks that wouldn’t naturally occur. “For a long time we really have not known what the conditions are inside a thunderstorm at the time and location that lightning initiates,” said Dwyer.

The opacity of storm clouds has until recently prevented scientists from seeing how lightning initiates.

The opacity of storm clouds has until recently prevented scientists from seeing how lightning initiates.

Corey Hochachka / Design Pics

So Dwyer and his team turned to the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), a network of thousands of small radio telescopes mostly in the Netherlands. LOFAR usually gazes at distant galaxies and exploding stars. But according to Dwyer, “it just so happens to work really well for measuring lightning, too.”

When thunderstorms roll overhead, there’s little useful astronomy that LOFAR can do. So instead, the telescope tunes its antennas to detect a barrage of a million or so radio pulses that emanate from each lightning flash. Unlike visible light, radio pulses can pass through thick clouds.

Using radio detectors to map lightning isn’t new; purpose-built radio antennas have long observed storms in New Mexico. But those images are low-resolution or only in two dimensions. LOFAR, a state-of-the-art astronomical telescope, can map lighting on a meter-by-meter scale in three dimensions, and with a frame rate 200 times faster than previous instruments could achieve. “The LOFAR measurements are giving us the first really clear picture of what’s happening inside the thunderstorm,” said Dwyer.

A materializing lightning bolt produces millions of radio pulses. To reconstruct a 3D lightning image from the jumble of data, the researchers employed an algorithm similar to one used in the Apollo moon landings. The algorithm continuously updates what’s known about an object’s position. Whereas a single radio antenna can only indicate the rough direction of the flash, adding data from a second antenna updates the position. By steadily looping in thousands of LOFAR’s antennas, the algorithm constructs a clear map.

When the researchers analyzed the data from the August 2018 lightning flash, they saw that the radio pulses all emanated from a 70-meter-wide region deep inside the storm cloud. They quickly inferred that the pattern of pulses supports one of the two leading theories about how the most common type of lightning gets started.

One idea holds that cosmic rays — particles from outer space — collide with electrons inside thunderstorms, triggering electron avalanches that strengthen the electric fields.

The new observations point to the rival theory. It starts with clusters of ice crystals inside the cloud. Turbulent collisions between the needle-shaped crystals brush off some of their electrons, leaving one end of each ice crystal positively charged and the other negatively charged. The positive end draws electrons from nearby air molecules. More electrons flow in from air molecules that are farther away, forming ribbons of ionized air that extend from each ice crystal tip. These are called streamers.

LOFAR, a large network of radio telescopes mostly in the Netherlands, records lightning when it isn’t doing astronomy.

LOFAR / ASTRON

Each crystal tip gives rise to hordes of streamers, with individual streamers branching off again and again. The streamers heat the surrounding air, ripping electrons from air molecules en masse so that a larger current flows onto the ice crystals. Eventually a streamer becomes hot and conductive enough to turn into a leader — a channel along which a fully fledged streak of lightning can suddenly travel.

“This is what we’re seeing,” said Christopher Sterpka, first author on the new paper. In a movie showing the initiation of the flash that the researchers made from the data, radio pulses grow exponentially, likely because of the deluge of streamers. “After the avalanche stops, we see a lightning leader nearby,” he said. In recent months, Sterpka has been compiling more lightning initiation movies that look similar to the first.

The key role of ice crystals dovetails with recent findings that lightning activity dropped by more than 10% during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers attribute this drop to lockdowns, which led to fewer pollutants in the air, and thus fewer nucleation sites for ice crystals.

“The steps set by LOFAR are certainly very significant,” said Ute Ebert, a physicist at the National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science and Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands who studies lightning initiation but was not involved in the new work. She said LOFAR’s initiation movies offer a framework from which to build accurate lightning models and simulations, which until now have been held back by a lack of high-resolution data.

Ebert notes, however, that despite its resolution, the initiation movie described in the new paper does not directly image ice particles ionizing the air — it only shows what happens immediately afterward. “Where is the first electron coming from? How does the discharge start near to an ice particle?” she asked. Few researchers still favor the rival theory that cosmic rays directly initiate lightning, but cosmic rays could still play a secondary role in creating electrons that trigger the first streamers that connect to ice crystals, said Ebert. Exactly how streamers turn into leaders is also a “matter of great debate,” said Hare.

Dwyer is hopeful that LOFAR will be capable of resolving these millimeter-scale processes. “We’re trying to see those first little sparks that come off [ice crystals] to capture the initiation action right at the very beginning,” he said.

Initiation is just the first of many intricate steps that lightning takes on its way to the ground. “We don’t know how it propagates and grows,” said Hare. “We don’t know how it connects to the ground.” Scientists hope to map the whole sequence with the LOFAR network. “It’s an entirely new capability, and I think it will increase our understanding of lightning in leaps and bounds,” said Julia Tilles, a lightning researcher at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico.

Correction: January 4, 2022

This article was amended to include Ute Ebert’s affiliation with the National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science.

Scientists have never been able to adequately explain where lightning comes from. Now the first detailed observations of its emergence inside a cloud have exposed how electric fields grow strong enough to let bolts fly.

In this animation of a lightning flash recorded by the LOFAR radio telescope network, each dot is the location of a radio source. The flash, which is 5 kilometers wide, grew out of a small region of the cloud measuring tens of meters across.

Brian Hare

Thomas Lewton

Contributing Writer

December 20, 2021

During a summer storm in 2018, a momentous lightning bolt flashed above a network of radio telescopes in the Netherlands. The telescopes’ detailed recordings, which were processed only recently, reveal something no one has seen before: lightning actually starting up inside a thundercloud.

In a new paper that will soon be published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers used the observations to settle a long-standing debate about what triggers lightning — the first step in the mysterious process by which bolts arise, grow and propagate to the ground. “It’s kind of embarrassing. It’s the most energetic process on the planet, we have religions centered around this thing, and we have no idea how it works,” said Brian Hare, a lightning researcher at the University of Groningen and a co-author of the new paper.

The schoolbook picture is that, inside a thundercloud, hail falls as lighter ice crystals rise. The hail rubs off the ice crystals’ negatively charged electrons, leading the top of the cloud to become positively charged while the bottom becomes negatively charged. This creates an electric field that grows until a gigantic spark jumps across the sky.

Yet the electric fields inside clouds are about 10 times too weak to create sparks. “People have been sending balloons, rockets and airplanes into thunderstorms for decades and never seen electric fields anywhere near large enough,” said Joseph Dwyer, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire and a co-author on the new paper who has puzzled over the origins of lightning for over two decades. “It’s been a real mystery how this gets going.”

A big impediment is that clouds are opaque; even the best cameras can’t peek inside to see the moment of initiation. Until recently, this left scientists little choice but to venture into the storm — something they’ve been trying since Benjamin Franklin’s famous kite experiment of 1752. (According to a contemporaneous account, Franklin attached a key to a kite and flew it beneath a thundercloud, observing that the kite became electrified.) More recently, weather balloons and rockets have offered snapshots of the interior, but their presence tends to interfere with the data by artificially creating sparks that wouldn’t naturally occur. “For a long time we really have not known what the conditions are inside a thunderstorm at the time and location that lightning initiates,” said Dwyer.

Corey Hochachka / Design Pics

So Dwyer and his team turned to the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), a network of thousands of small radio telescopes mostly in the Netherlands. LOFAR usually gazes at distant galaxies and exploding stars. But according to Dwyer, “it just so happens to work really well for measuring lightning, too.”

When thunderstorms roll overhead, there’s little useful astronomy that LOFAR can do. So instead, the telescope tunes its antennas to detect a barrage of a million or so radio pulses that emanate from each lightning flash. Unlike visible light, radio pulses can pass through thick clouds.

Using radio detectors to map lightning isn’t new; purpose-built radio antennas have long observed storms in New Mexico. But those images are low-resolution or only in two dimensions. LOFAR, a state-of-the-art astronomical telescope, can map lighting on a meter-by-meter scale in three dimensions, and with a frame rate 200 times faster than previous instruments could achieve. “The LOFAR measurements are giving us the first really clear picture of what’s happening inside the thunderstorm,” said Dwyer.

A materializing lightning bolt produces millions of radio pulses. To reconstruct a 3D lightning image from the jumble of data, the researchers employed an algorithm similar to one used in the Apollo moon landings. The algorithm continuously updates what’s known about an object’s position. Whereas a single radio antenna can only indicate the rough direction of the flash, adding data from a second antenna updates the position. By steadily looping in thousands of LOFAR’s antennas, the algorithm constructs a clear map.

When the researchers analyzed the data from the August 2018 lightning flash, they saw that the radio pulses all emanated from a 70-meter-wide region deep inside the storm cloud. They quickly inferred that the pattern of pulses supports one of the two leading theories about how the most common type of lightning gets started.

One idea holds that cosmic rays — particles from outer space — collide with electrons inside thunderstorms, triggering electron avalanches that strengthen the electric fields.

The new observations point to the rival theory. It starts with clusters of ice crystals inside the cloud. Turbulent collisions between the needle-shaped crystals brush off some of their electrons, leaving one end of each ice crystal positively charged and the other negatively charged. The positive end draws electrons from nearby air molecules. More electrons flow in from air molecules that are farther away, forming ribbons of ionized air that extend from each ice crystal tip. These are called streamers.

LOFAR, a large network of radio telescopes mostly in the Netherlands, records lightning when it isn’t doing astronomy.

LOFAR / ASTRON

Each crystal tip gives rise to hordes of streamers, with individual streamers branching off again and again. The streamers heat the surrounding air, ripping electrons from air molecules en masse so that a larger current flows onto the ice crystals. Eventually a streamer becomes hot and conductive enough to turn into a leader — a channel along which a fully fledged streak of lightning can suddenly travel.

“This is what we’re seeing,” said Christopher Sterpka, first author on the new paper. In a movie showing the initiation of the flash that the researchers made from the data, radio pulses grow exponentially, likely because of the deluge of streamers. “After the avalanche stops, we see a lightning leader nearby,” he said. In recent months, Sterpka has been compiling more lightning initiation movies that look similar to the first.

The key role of ice crystals dovetails with recent findings that lightning activity dropped by more than 10% during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers attribute this drop to lockdowns, which led to fewer pollutants in the air, and thus fewer nucleation sites for ice crystals.

“The steps set by LOFAR are certainly very significant,” said Ute Ebert, a physicist at the National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science and Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands who studies lightning initiation but was not involved in the new work. She said LOFAR’s initiation movies offer a framework from which to build accurate lightning models and simulations, which until now have been held back by a lack of high-resolution data.

Ebert notes, however, that despite its resolution, the initiation movie described in the new paper does not directly image ice particles ionizing the air — it only shows what happens immediately afterward. “Where is the first electron coming from? How does the discharge start near to an ice particle?” she asked. Few researchers still favor the rival theory that cosmic rays directly initiate lightning, but cosmic rays could still play a secondary role in creating electrons that trigger the first streamers that connect to ice crystals, said Ebert. Exactly how streamers turn into leaders is also a “matter of great debate,” said Hare.

Dwyer is hopeful that LOFAR will be capable of resolving these millimeter-scale processes. “We’re trying to see those first little sparks that come off [ice crystals] to capture the initiation action right at the very beginning,” he said.

Initiation is just the first of many intricate steps that lightning takes on its way to the ground. “We don’t know how it propagates and grows,” said Hare. “We don’t know how it connects to the ground.” Scientists hope to map the whole sequence with the LOFAR network. “It’s an entirely new capability, and I think it will increase our understanding of lightning in leaps and bounds,” said Julia Tilles, a lightning researcher at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico.

Correction: January 4, 2022

This article was amended to include Ute Ebert’s affiliation with the National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)