Staff Writer | November 30, 2022

Mine workers. (Reference image by Pranshu Goyal, Pixahive.)

A recent report led by researchers at Curtin University has found that Australian mining companies have a stronger focus on employees’ physical health and safety than on their mental health and well-being.

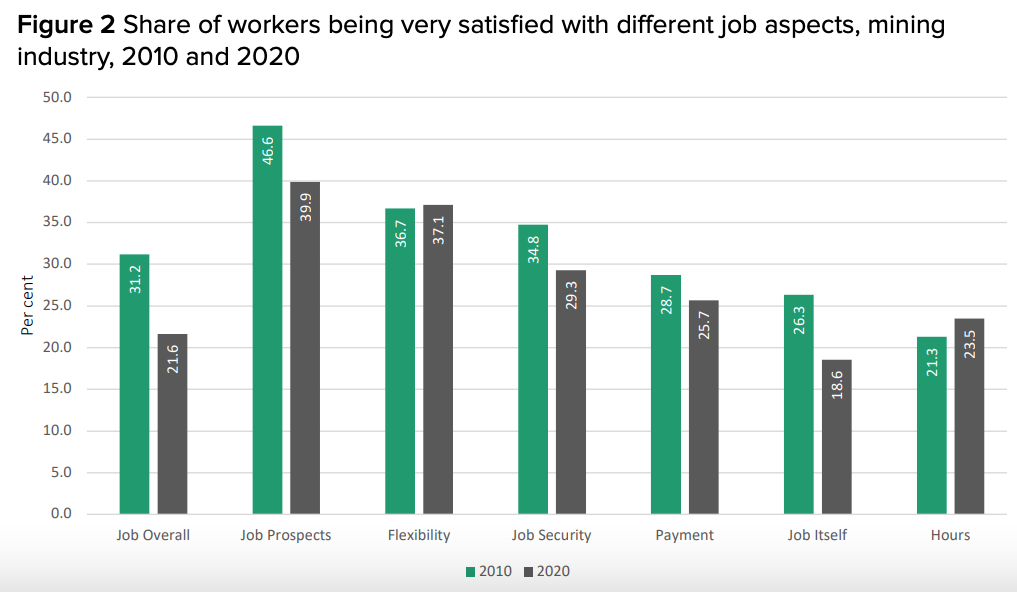

The study examined employee welfare in the mining sector and found that only 22% of workers were very satisfied with their overall job, with employees experiencing poor job satisfaction, job security and job prospects compared to other industries.

By reviewing secondary evidence from the Australian Human Rights Commission, the authors of the report also found the mining sector is one of the worst five industries in the country in relation to sexual harassment issues, with 40% of workers and 74% of female workers reporting sexual harassment in the last five years.

The dossier develops a unique index to capture the prioritization of employee health and well-being based on mining companies’ public reports and found that many of them, particularly those that are larger or have women at the helm, are prioritizing well-being. However, only 33% refer to loneliness, social connection, or isolation in their reports, and only 50% of mining companies refer to sexual harassment, assault, and sexism.

(Graph from the “Towards a healthy and safe workforce in the mining industry: A review and mapping of current practice” report).

According to Astghik Mavisakalyan, co-author of the study and a professor at the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, all of these factors contribute to the mining industry rating the lowest among all Australian industries for job satisfaction.

“We found that while mining sector workers experienced good physical health and were more satisfied with their jobs now compared to 15 years ago, the number of very satisfied workers was the lowest of all industries,” Mavisakalyan said. “The report also showed that the levels of high distress of mining sector workers had risen considerably in the past decade, from 9% in 2009 to 15% in 2019.”

For Mavisakalyan and her colleagues, it is important to identify and support employees that are experiencing poor mental health and proactively create a healthy work environment.

“This means developing work cultures in which women are welcome and accepted, as well as, for all workers, having meaningful jobs with decent rosters, acceptable levels of job demands, and supportive managers,” Sharon Parker, a researcher at Curtin’s Future of Work Institute, said.

“Having anti-harassment and mental health policies is necessary but not sufficient. These policies need to be backed up by on-the-ground support, such as effective systems for reporting harassment, and education and training of managers to effectively implement the policies.”

Parker and Mavisakalyan also mentioned this report is the first contribution to a major project that is intended to promote positive and effective change for those working in the mining industry who might be experiencing poor mental health and well-being, as well as those subjected to sexual harassment in the workplace.

According to Astghik Mavisakalyan, co-author of the study and a professor at the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, all of these factors contribute to the mining industry rating the lowest among all Australian industries for job satisfaction.

“We found that while mining sector workers experienced good physical health and were more satisfied with their jobs now compared to 15 years ago, the number of very satisfied workers was the lowest of all industries,” Mavisakalyan said. “The report also showed that the levels of high distress of mining sector workers had risen considerably in the past decade, from 9% in 2009 to 15% in 2019.”

For Mavisakalyan and her colleagues, it is important to identify and support employees that are experiencing poor mental health and proactively create a healthy work environment.

“This means developing work cultures in which women are welcome and accepted, as well as, for all workers, having meaningful jobs with decent rosters, acceptable levels of job demands, and supportive managers,” Sharon Parker, a researcher at Curtin’s Future of Work Institute, said.

“Having anti-harassment and mental health policies is necessary but not sufficient. These policies need to be backed up by on-the-ground support, such as effective systems for reporting harassment, and education and training of managers to effectively implement the policies.”

Parker and Mavisakalyan also mentioned this report is the first contribution to a major project that is intended to promote positive and effective change for those working in the mining industry who might be experiencing poor mental health and well-being, as well as those subjected to sexual harassment in the workplace.