Hilary Whiteman, CNN

Mon, September 4, 2023 at 10:14 PM MDT·10 min read

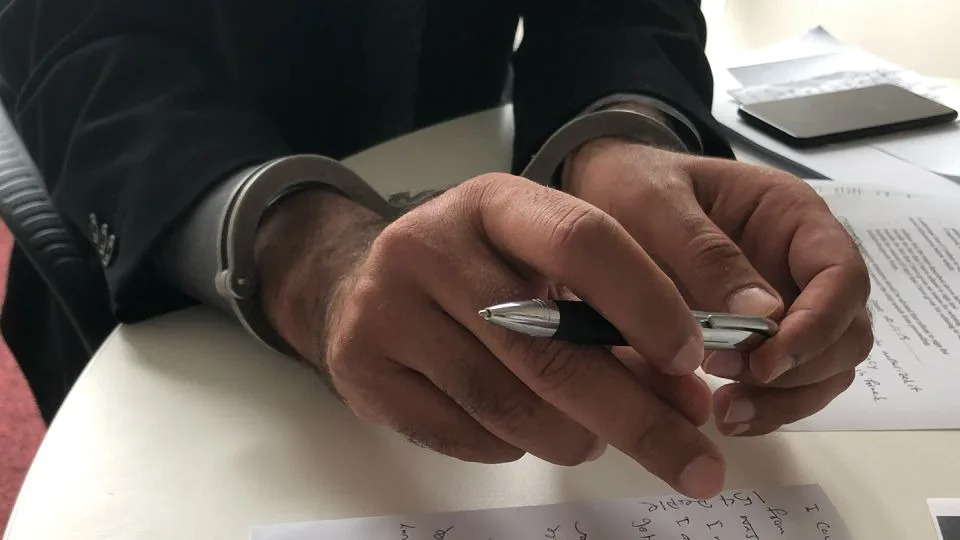

With his hands cuffed, Ned Kelly Emeralds scribbles awkwardly on a piece of paper inside a Brisbane courthouse as he hurriedly tries to tell his story after years of immigration detention.

It’s 2019, and Emeralds can’t speak, not because guards are waiting outside the meeting room door, but because he’s been mute since he woke after trying to take his own life in detention on Christmas Island soon after arriving in Australian waters on a refugee boat in 2013.

Emeralds was in court to seek a protection order against an immigration detention center supervisor who he accused of bullying. It was one of many court hearings initiated by Emeralds as he pushes back on a system that has kept him behind bars for 10 years.

On Wednesday the High Court of Australia will deliver a ruling related to one of his more significant cases, which could give new hope to at least 130 detainees facing indefinite detention and others held for long periods in immigration limbo.

The High Court will decide if the Federal Court has the power to order the government to hold detainees in places other than formal detention centers, including the private homes of their supporters.

“It will have vast implications for people who are subject to indefinite immigration detention and who the government has not bothered to remove from Australia or find some other solution within a reasonable period,” said Emeralds’ lawyer Sanmati Verma, from the Human Rights Law Centre.

However, Verma said Emeralds doesn’t stand to gain from any High Court win because of an extraordinary decision by the previous Home Affairs minister to change his status to circumvent a court order – a move that can only be altered by another ministerial intervention.

Emeralds’ situation has become so hopeless that last year he sought a friend’s help to apply for voluntary euthanasia, which is legal in Western Australia, where he is being held.

“Ned’s case is kind of like an exploration of all of the Kafkaesque aspects of Australia’s immigration detention and asylum regimes,” Verma said. “There’s no earthly reason why Ned should be detained.”

In a statement to CNN, a spokesperson for Australia’s Home Affairs department said it does not comment on individual cases.

Escape from Iran

The man who adopted the name Ned Kelly Emeralds, in homage to the famous Australian bushranger, fled Iran in July 2013.

At the time, the Australian government was fortifying its immigration policy to deal with an influx of asylum seeker boats, but hadn’t yet told new arrivals they would never settle in the country. That came days later, when Emeralds, then 27, was already detained in the northern city of Darwin.

He was soon flown to the small Australian territory of Christmas Island, where it would be two years before he’d be invited to apply for a visa. In that time, his personal information was among 10,000 records leaked online by a government error, exposing sensitive details about why he’d fled Iran, according to the government’s own admission. For him, the stress and the stakes were higher than ever.

By the time Emeralds was asked to explain at a formal interview why he was seeking asylum, a suicide attempt had robbed him of his voice. He scrawled answers to questions on paper, saying he was a metallurgical engineer who feared persecution because he had renounced his faith, an illegal act in Iran.

Iranian asylum seeker Ned Kelly Emeralds has been mute for almost a decade and writes or texts to communicate. - Hilary Whiteman/CNN

In May 2016, the Australian official made a preliminary finding that he was owed protection. But no visa was offered, and it was two years before he was told that a new official had taken up his case, who subsequently refused his claim.

Verma believes Emeralds’ mutism worked against him.

“How do you assess the credibility of somebody who is psychogenically mute, and who is providing responses to your questions as quickly as they can, but in writing that’s being read out to the decision maker? How do you form the kind of usual cornerstones of credibility that are spontaneity, detail. How do you do that?”

Emeralds challenged the negative ruling multiple times, and in 2021, the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA) found again that he wasn’t owed protection.

“The person who decided his protection visa application was negative never met Ned,” Verma said. “Certainly, none of the reviewers at the IAA ever bothered to meet Ned. They deal with him on the papers.”

In the statement, the Home Affairs department spokesperson said a “non-citizen’s status is resolved through either a substantive visa grant or departure from Australia.” The latter is not an option for Emeralds, because Iran doesn’t accept involuntary returnees, and without a visa he remains stuck in the system.

Facing a life of indefinite detention, Emeralds’ lawyers sought a ruling of habeas corpus – unlawful detention – but that again hit a roadblock in June 2021, when the High Court ruled in another case that indefinite detention in Australia is legal.

Verma said other asylum seekers who had hoped the ruling would see them freed, withdrew their applications for fear the likely outcome was a transfer offshore to Nauru, the scene of trauma recounted by other detainees, the last of whom was transported off the island in June 2023.

But not Emeralds.

“Ned was one of these unique people, where he was sort of like, well, you know, liberty’s liberty,” Verma said.

His lawyers pressed forward with a claim that Emeralds should have been sent offshore within days of this arrival in 2013, alleging the government had failed in its duty to remove him.

The argument worked.

A brush with freedom

On October 27, 2021, Emeralds came so close to being freed that he was sitting with his bags packed at a bus stop at Perth Immigration Detention Centre, waiting to be picked up.

Two weeks before, on October 13, 2021, Justice Darryl Rangiah had ruled that Emeralds should be transferred from the detention center to a private six-bedroom house, while the Australian government started the process of transferring him to Nauru.

Annette and Miguel Castillo had hurriedly cleared a room for their guest, whom Annette knew from her visits to the detention center.

But the day didn’t proceed as planned.

“He was waiting all day sitting there, and we were on the other side, sitting all day and waiting for him,” Annette Castillo told CNN at the time.

“We cleaned the whole room, we put furniture in, so it was a big undertaking. We’re very happy to do that, and we can help him, but at least they should have told us he wouldn’t come.”

That morning however, Nauru had informed Australia they wouldn’t accept him.

Karen Andrews, Home Affairs Minister at the time, then personally intervened to change his status so he didn’t require offshore processing, which negated the need to house him while those arrangements were made. A notice seen by CNN said the decision was made “in the public interest.”

CNN asked the Nauru government why he was rejected but didn’t receive a response. A spokesperson for Andrews declined to comment, saying the “management of individuals in immigration detention is a matter for the current government.”

Weeks later, in a move that seemed to rub salt into wounds, the government appealed the original ruling – and won.

The Full Court of the Federal Court of Appeal found in April 2022 that the Federal Court doesn’t have the power to order the government to hold detainees at a specific location.

The High Court’s final ruling on the matter this week will decide if it does.

Protests in Perth

Annette Castillo met Emeralds through a friend when she regularly visited people in detention centers. She doesn’t go now because of the stress of their stories.

“I have a heart condition and each time I come home, I have to go to hospital,” she said. “I get so upset.”

Dawn Barrington (third from left) has been holding weekly protests with others calling for Emeralds' freedom. - Courtesy Dawn Barrington

Others supporters have stepped in to text and visit Emeralds in detention, including musician and activist Dawn Barrington, who was the friend who agreed to help him pursue voluntary euthanasia.

“I didn’t try and talk him out of it,” she said.

“I basically said there’s a strict criteria, so it’s highly unlikely that they will let it go through … I think that going through that process was just another example of how hopeless the situation was because it’s like there’s no way out for him.”

Barrington told Fran Hamilton about Emeralds’ situation and she said she was so “horrified” that most Fridays she now gathers with protesters outside St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Perth, holding a sign saying “Free Ned.”

“Everyone I speak to, once they know, they’re really shocked that the Australian government is doing this,” Hamilton said.

Rev. Gemma Baseley, the church’s rector, said she has sat with Emeralds during his various hunger strikes, when he’s been “very, very low,” and now regularly visits him at Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Center, over an hour’s drive from Perth.

“You’d think it would be a really depressing visit, and it never is, like he’s so funny,” she said. “I wonder if part of his way of coping is to just let go of hope, which is horrific. That surely is the cruelest thing we can do to someone – to make them believe there is no hope.”

Emeralds told CNN by text that he prefers not to involve his supporters in all his “difficulties, at least not in details, they have a life to live outside.”

“For me (their support) is priceless, helping without expecting to have it back,” he added.

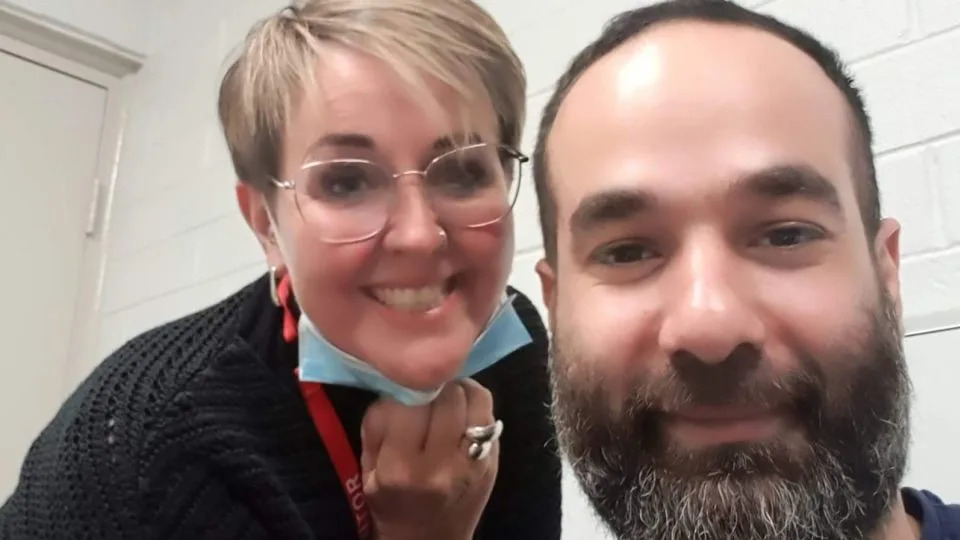

Rev. Gemma Baseley is among a group of supporters who regularly visit Ned Kelly Emeralds in detention. - Cortesy Rev. Gemma Baseley

Ten years behind bars

Emeralds may have supporters during his long period of detention, but he has angered some detention center staff by filming them, according to videos posted online to his various social media accounts.

He regularly shares videos of protests by other detainees, drawing attention to life on the inside and railing against the system and those who run it. The authorities consider him a troublemaker, according to multiple people who know him.

The years of detention have taken their toll on Emeralds’ mental health, according to clinical psychologist Guy Coffey, whose assessment was included in the High Court submission.

Coffey found “the largest contribution to his mental state has been his extended detention,” and he didn’t “anticipate any significant improvement in his mental health while he is detained in his current circumstances.”

Emeralds told CNN he stopped thinking about freedom the day the minister refused to honor a court order and left him waiting for hours at a bus stop before he was told be wouldn’t be leaving.

Asked this week how he was holding up, Emeralds texted: “Getting used to a cage, which cannot be done ever.”

Verma says the new Labor government should have moved to free him five weeks ago when ASIO – Australia’s intelligence agency – confirmed that he doesn’t pose a risk to national security.

“Five weeks in the context of somebody’s deprivation of liberty for a decade, there should be the highest degree of urgency,” she said. “Ned remains one of the longest serving detainees who’s still there. You would expect an almost daily watching brief.

“There are two ministers capable of exercising that power. It’s five weeks too long.”

The Home Affairs department spokesperson said in the statement that portfolio ministers only intervene in a “relatively small number of cases where they consider that it is in the public interest.”

“What is in the public interest is for the Minister to determine,” the statement added.