New manzanita species discovered, already at risk

Famously twisted shrub mainly grows in California

Peer-Reviewed Publicationimage:

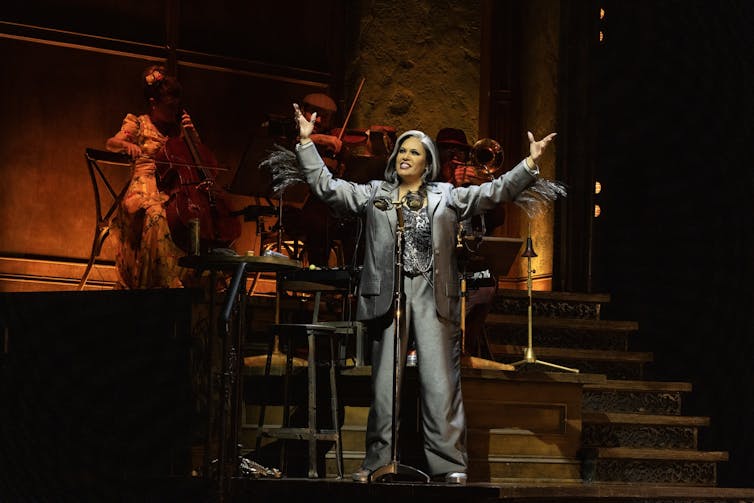

Young A. Nipumu flowers.

view moreCredit: Abbo et al., 2025/PhytoKeys

A new species of manzanita — a native California shrub famous for its twisted branches and wildfire resilience — has been discovered on the central coast, but its survival is already threatened by urban development that could destroy much of its fragile population.

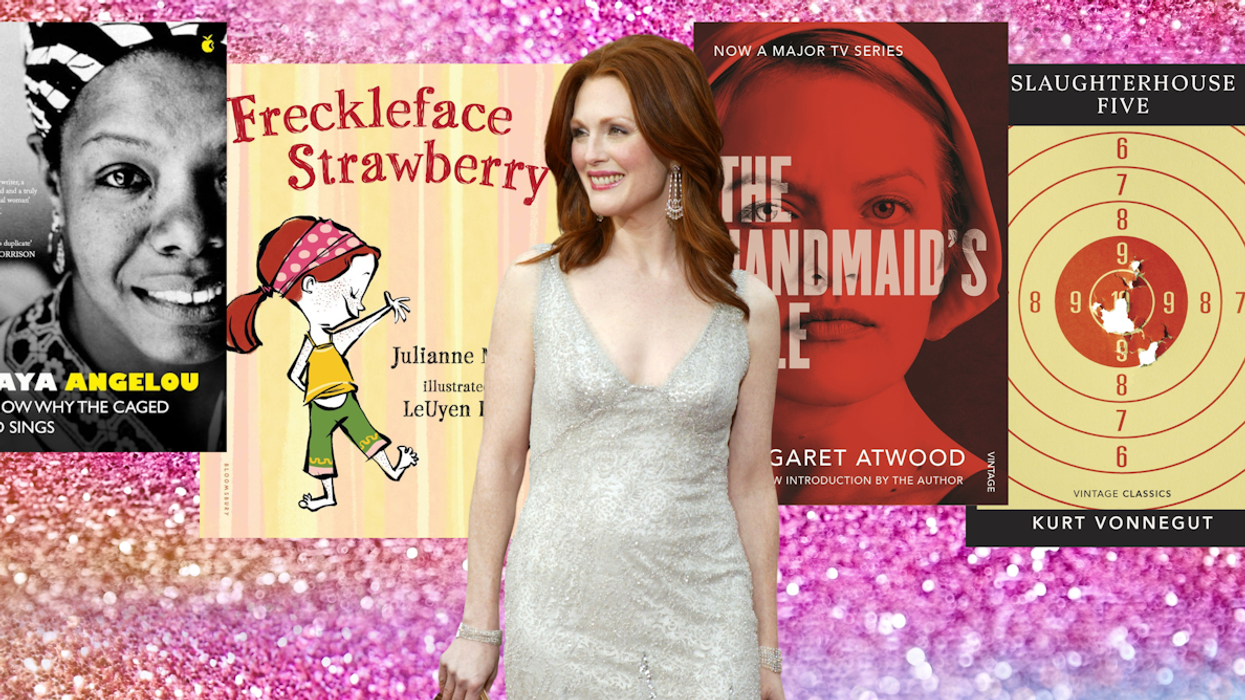

The discovery is detailed in a new study published in PhytoKeys, where researchers used genetic analysis to confirm the plant as a distinct species. Named Arctostaphylos nipumu to honor the Nipomo Mesa where it was discovered and its indigenous heritage, the species stands out for its shaggy gray bark — unlike the iconic red bark found on most California manzanitas.

Manzanitas are a signature part of California’s natural landscapes, celebrated for their twisting branches, smooth red bark, and remarkable adaptability to fire-prone environments. With more than 60 species native to the state, they play a crucial role in local ecosystems, providing food and shelter for wildlife. Historically, it has also been central to the lives of Indigenous tribes, who used its berries for food, its leaves for medicine, and its wood for tools and firewood.

Beyond California’s borders, only a few species exist, making the state a global center for manzanita diversity. The addition of A. nipumu deepens this rich botanical legacy.

“We weren’t expecting to find a new species in such a developed area,” said UC Riverside plant biologist and study coauthor Amy Litt. “But as we examined the plants, we realized the Nipomo Mesa plants were quite distinct. We were subsequently able to show that they not only look different but are genetically unique.”

Like many manzanitas, A. nipumu relies on fire to trigger seed germination, but it lacks a protective burl that allows some species to resprout after wildfires. The lack of burl also means it is not certain that the plants would survive attempts to move them to a new location.

With fewer than 700 individuals — possibly as few as 300 — remaining in the wild, A. nipumu is highly vulnerable. Its fragmented habitat now faces a major threat from the Dana Reserve Project, a recently approved housing development. According to maps included in the study, the project could impact up to half of the manzanita’s remaining population.

Researchers have shared their findings with local officials to highlight the potential ecological implications of the project. “Our goal is to inform ongoing conversations about conservation,” said plant geneticist and paper co-author Bill Waycott, with the California Native Plant Society.

Environmental groups, including the California Native Plant Society, say the discovery of A. nipumu has further underscored the ecological significance of the Nipomo Mesa.

This situation highlights broader challenges in habitat restoration. Replanting native species often relies on nursery stock that lacks the genetic diversity of wild populations, making them more vulnerable to disease and environmental stress. “When you propagate from just a few individuals, you have a limited pool of genetic diversity and potentially less variation in natural plant defenses,” said Tito Abbo, study coauthor and graduate student in the Litt laboratory.

As urban expansion continues, scientists warn that once habitats like the Nipomo Mesa are lost, they are difficult — if not impossible — to fully restore. “This manzanita isn’t just a plant,” Abbo said. “It’s part of what makes this ecosystem unique. Losing it would mean erasing a piece of California’s natural history and heritage.”

With legal battles ongoing and construction plans advancing, the future of A. nipumu remains uncertain. But its formal recognition offers a crucial first step toward its protection. “We need to learn how to live with this species and many others in urban environments that interface with nature,” Waycott said.

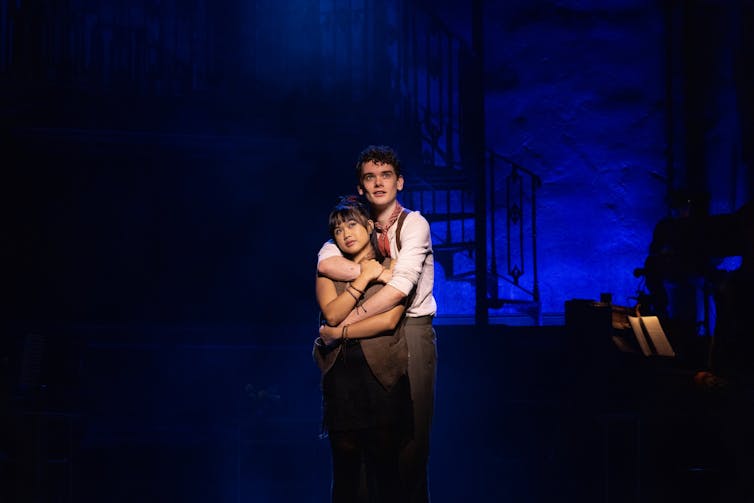

The research team surveying plants on California's central coast.

Unusual twisted gray bark of A. Nipumu.

Credit

Morgan Stickrod/UCR

Article Title

Investigating a hybrid mixed population leads to recognizing a new species of Arctostaphylos (Ericaceae)