Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: Defensive response or imperialist aggression?

In his article, “What’s really at stake in Ukraine”, Dave Holmes portrays Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a defensive response to NATO expansion. Explaining Putin’s motivation, Holmes writes:

The simple answer is that Russia invaded because it was seriously worried about NATO’s intentions; it had warned for years and years that NATO activity in Ukraine was an existential red line for Moscow.

Even if it were true that Russian President Vladimir Putin was “worried about NATO’s intentions”, that still would not justify the invasion. Pre-emptive war was not the only option. Moreover, it was counterproductive as it stoked fear of Russian aggression in other European countries, leading to Finland and Sweden joining NATO, as well as rising military expenditure in other countries. The invasion was a gift to NATO.

Holmes quotes Martin Luther King who said the US government is “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today”, and says this remains true today. I agree the US is the main purveyor of violence — but it is not the only one. Putin’s Russia is also a major source of violence.

Russia’s economic and military power

Holmes writes:

According to World Beyond War, the US has 877 foreign military bases, absolutely dwarfing all other countries put together. The bases are there to defend Washington’s world empire.

Russia has fewer bases outside its own borders than the US, but Russia’s military intervention in other countries is significant.

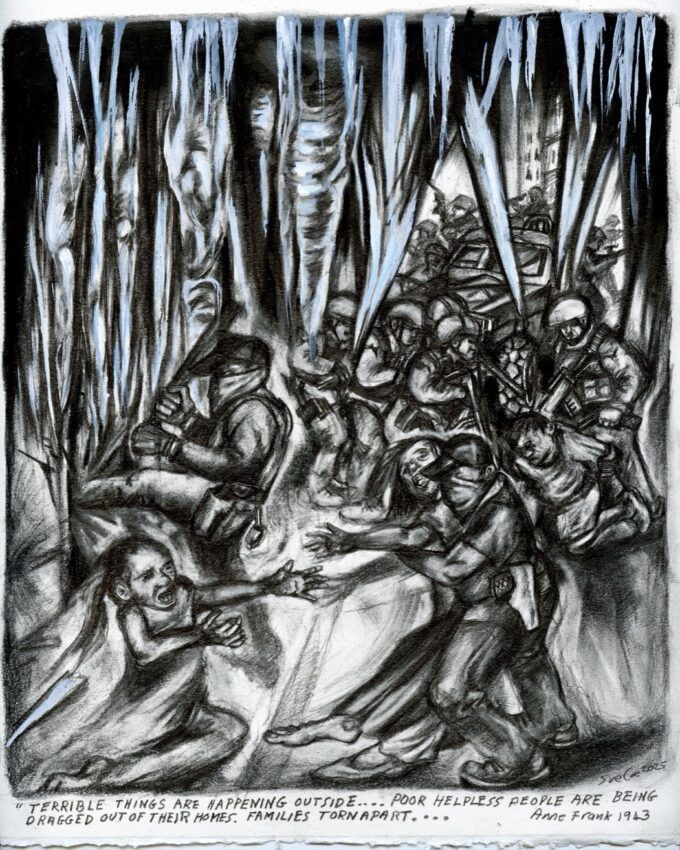

In addition to Ukraine, Russia has intervened in other neighbouring countries, such as Georgia. It has also sent military forces to countries much further away. For example, Russian aircrafts bombed rebel-held areas in Syria, causing widespread death and destruction in a failed attempt to prop up the Bashar al-Assad regime.

With the approval of the Russian government, Russian mercenaries employed by the Wagner Private Military Company have been involved in wars in a number of African countries. In Sudan they worked with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group allied to the military dictatorship. The RSF repressed ethnic minorities and democracy activists while Wagner profited from gold mining in Sudan and elsewhere.1 [1]

The RSF later came into conflict with the Sudanese regular army, resulting in a civil war that continues today. Putin disbanded the Wagner private army in 2023 after its leader Yevgeny Prigozhin launched a rebellion against the Russian government, but some Wagner troops were then incorporated into the Russian army. Today Russia still has military personnel in several African countries.

Holmes writes:

We can trace US hostility to Russia back to the 1917 Bolshevik-led revolution… Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the hostility continued.

This is a one-sided analysis. The US supported the Boris Yeltsin regime in Russia in the 1990s. At the time, the US trusted Russia more than Ukraine. Hence the US insisted that nuclear weapons on Ukrainian soil be transferred to Russia. This was completed by 1996, with assistance from the US-funded Cooperative Threat Reduction Program.2

However, the US did not want Russia to become strong enough to be an imperialist rival. Putin, on the other hand, wants Russia to once again become a great power. This has led to a rise in conflict between the US and Russia.

Holmes writes:

In one sense Russia is a big capitalist country: It is the world’s largest country by area and measured by PPP [purchasing power parity] its GDP is fourth in the world. But its per capita GDP is way down on the list making it definitely part of the Global South, and in no way a part of the imperialist club.

In reality, Russia holds an intermediate position in terms of GDP. It is not at the top of the list, but nor is it near the bottom. Russia was 47th out of 191 countries in GDP (PPP) per capita in 2023.3 This means its GDP (PPP) per capita was higher than more than 70% of countries.

Economically, Russia is intermediate between the richest imperialist countries, such as the US, and the poorest semi-colonial countries, such as Sudan. In 2023, Russia’s GDP (PPP) per capita was 16 times higher than Sudan’s, which was 170th on the list.

Furthermore, Russia’s military strength means it more closely resembles the US than Sudan.

In 1916, Vladimir Lenin viewed Russia and Japan as imperialist powers, despite the limited development of finance capital in those countries. He said:

The last third of the nineteenth century saw the transition to the new, imperialist era. Finance capital not of one, but of several, though very few, Great Powers enjoys a monopoly. (In Japan and Russia the monopoly of military power, vast territories, or special facilities for robbing minority nationalities, China, etc, partly supplements, partly takes the place of, the monopoly of modern, up-to-date finance capital.)4

Tsarist Russia was a relatively poor and backward state, but Lenin still considered it imperialist because of its military power, its robbery of national minorities, and other factors. Today, Russia’s military strength is evidence of its status as an imperialist power.

Relations among imperialist powers are often hostile. Lenin believed that conflict among great powers is an inevitable feature of imperialism. As such, there is no “imperialist club”.

Maidan and Donbas

Holmes writes:

The February 2014 Maidan upheaval in Ukraine was a watershed moment in the country’s history. Its meaning is completely clear. An elected government (actually not at all opposed to the West) was overthrown and a more nakedly pro-US regime was installed, based on the far right.

This is a one-sided account. It neglects the role that popular discontent and anger at a corrupt regime played in causing the Maidan rebellion.

In today’s world, it often happens that oppression gives rise to protest, but that the weakness of the left means right-wing forces dominate the movement. The Maidan rebellion is an example of this.

Holmes quotes Andriy Manchuk, who said:

The right-wing ideology is a kind of synthesis of neoliberal illusions about the nature of “decent European capitalism” and clerical bigotry of Ukrainian nationalism. It dominated in the Euromaidan protests from the very beginning and almost everything there was under control of right-wing politicians. They managed to exploit the anger of many impoverished and marginalised Ukrainians dissatisfied with the corrupt bourgeois regime of Yanukovich — the regime that we also have been fighting against for many years.

After 20 years of mass anti-communist propaganda, the left in Ukraine was pushed into the margins of politics while the right wing used social populism combined with pro-capitalist and nationalist slogans to make political gains.

That is true. But the “anti-Maidan” revolt in Donbas in 2014 suffered a similar fate. A popular revolt occurred, yet reactionary forces gained control of that movement. There was also intervention by Russian ethnonationalists, and then by the Russian army.

Holmes quotes Renfrey Clarke, who writes:

In reality, and as this article will demonstrate, the Donbass revolt was a local initiative that had very robust popular origins, particularly in the region’s coal-mining communities. A key immediate source was a spontaneous, defensive response to the threat of armed attacks by ultra-right Ukrainian nationalist bands allied with the new Kyiv government of Prime Minister Arsenyi Yatseniuk. At a more elemental level, the uprising rested on working-class resistance to a program of neoliberal austerity being readied for implementation by the new Kyiv authorities.

This popular upsurge was one aspect of the Donbas revolt. But Russian ethnonationalists played a key role in the armed conflict, just as Ukrainian ethnonationalists did on the other side. For example, Igor Girkin (aka Strelkov), a former officer in the Russian FSB (Federal Security Service), led an armed group that took over the city of Sloviansk. The Russian Imperial Movement was also active in eastern Ukraine.

Clarke writes:

With its pronounced component of working-class struggle, the Donbass revolt was at odds in fundamental respects with the Russian administration — conservative, despite its populism — of President Vladimir Putin. The formidable sympathy for the rebellion among the population in Russia nevertheless constrained Putin from joining with the new Ukrainian authorities to suppress an essentially unwelcome development. Obliged to support the revolt to the point needed to allow its survival, the Russian government exerted strong pressure on the rebels to limit their radicalism.

I would add that Russian authorities violently suppressed the progressive aspects of the Donbas rebellion. Russian socialist Boris Kagarlitsky, who supported the rebellion in its early period, says it was quickly undermined and repressed.5

According to Kagarlitsky, there were “three sides” in the conflict: the Ukrainian government, the Russian government and the local people. The 2014 Donbas rebellion was a response by local people to the overthrow of the Yanukovych government, which most people in eastern Ukraine had voted for. For them the new government in Kyiv had “no legitimacy”. They saw it as the product of a coup.

Kagarlitsky says the Donbas uprising was a “popular rebellion”. But Russia’s intervention changed the situation. The Russian government “did everything to undermine the popular democratic movement”. Many of the uprising’s leaders were murdered by pro-Russian forces. Today, the Donbas “people's republics” are run by “totally corrupt puppets installed by Moscow.”

Holmes writes:

Under the post-Maidan regimes Ukraine has become completely subordinated to the West. Western advisers are everywhere, not only in the military and security services but also in other state institutions.

That is true, but it is also true that eastern Ukraine is totally subordinated to Russia. Thus, the war in Donbas became a conflict between a Ukrainian government subservient to Western imperialism and reactionary puppet regimes in eastern Ukraine subservient to Russia. The conflict increasingly resembled an inter-imperialist proxy war.

But Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 changed the situation, converting it into a war of aggression by an imperialist power (Russia) against a semi-colonial country (Ukraine).

Chauvinism in Ukraine and Russia

Holmes writes:

There may well be Nazi-minded groups in Russia but they are small, isolated and reviled and don’t remotely control or set government policy. The Putin regime’s ideological stance is not Nazi but stresses conservative and Russian nationalist themes (restrictions on LGBTIQ rights, lauding the Russian Orthodox church, and so on).

But in Ukraine today, Ukrainian Nazis (harking back to wartime Nazi-collaborator Stepan Bandera) have grown markedly stronger during the war and are now a significant force.

Yet Putin has promoted an ideology of Great Russian chauvinism. This is reflected in his denial that Ukraine is a nation. It is also reflected in his glorification of some of the tsars, especially Peter the Great, who greatly expanded the Russian empire.6

Ceasefire and concessions

Holmes writes:

Peace is the key need for ordinary Ukrainians: A stop to the war and the killing, reconstruction and a return to some sort of normality.

An August 7 Gallup poll found that 69% of Ukrainians want peace as soon as possible even if it means territorial concessions; only 24% want to keep on fighting. This is a sharp reversal of the sentiment several years earlier.

Facing a militarily stronger enemy, Ukraine may have to make territorial concessions. There are precedents for this.

Under the Brest-Litovsk treaty, signed in 1918, the Bolsheviks allowed German imperialism to keep territory it had seized during World War I. Less than a year later, a rebellion by German workers, soldiers and sailors ended the war and ended German occupation of this territory.

The Irish War of Independence (1919-21) ended in a peace treaty that allowed Britain to keep six counties in the north of the island. Some independence fighters opposed the treaty as a sell-out, leading to a civil war among republicans. Pro-treaty forces won the war, but the outcome was a divided Ireland, with reactionary political regimes in control of both parts.

So, a peace agreement involving territorial concessions can create new problems. Nevertheless, Ukraine may have to accept it. If so, they will have to hope that, as in Germany in 1918, rebellion in Russia leads to the end of the occupation.

Spheres of influence

Holmes quotes Ray McGovern, who says:

14 years ago, then U.S. Ambassador to Russia (current CIA Director) William Burns was warned by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov that Russia might have to intervene in Ukraine, if it were made a member of NATO. The subject line of Burns’s Feb. 1, 2008 Embassy Moscow cable (#182) to Washington makes it clear that Amb. Burns did not mince Lavrov’s words; the subject line stated: “Nyet means nyet: Russia’s NATO enlargement redlines.” Thus, Washington policymakers were given forewarning, in very specific terms, of Russia’s redline regarding membership for Ukraine in NATO.

Lavrov’s claim that Russia has the right to intervene in Ukraine if it joins NATO is reminiscent of the Monroe Doctrine, whereby the US claimed the right to intervene in Latin American countries to stop rival powers from doing so.

The implication of Lavrov’s comment is that Russia claims a sphere of influence covering neighbouring countries, such as Ukraine. We should not accept this.

If Mexico were to form a military alliance with China and Russia, this would no doubt be a “red line” for the US government, which might feel entitled to invade Mexico to prevent it. We would oppose such an invasion. Similarly, we should oppose Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The military situation

Holmes writes:

Has the Russian military intervention been a failure? Has it simply been “counterproductive”? I don’t think so.

Firstly, there is the military balance sheet. After three and half years of fighting, Moscow is clearly inflicting a serious defeat on the US-NATO-Ukraine forces. There is a way to go but it is hard to see Russia’s battlefield dominance being reversed. There is a real danger of World War III, given Ukraine’s repeated deep strikes into Russia (all of which necessitate Western approval, planning and technical involvement).

It does appear that Russian troops are advancing in eastern Ukraine. This is not surprising. Russia is militarily stronger than Ukraine. It has a much larger population, so it has more potential soldiers. It has a larger military industry. It has nuclear weapons. Hence Russia may well win a military victory.

This does not mean we should therefore support Russia’s actions.

Our policy

Instead, socialists should continue to condemn Russia’s invasion. But we should recognise that there is little prospect of a Ukrainian military victory and call for a ceasefire.

If Russia does not agree to a ceasefire, then we should call for Ukraine to receive the military aid it needs to prevent Russia conquering even more Ukrainian territory.

If a ceasefire is implemented, we should call for a United Nations-supervised referendum in the Donbas.

We should also continue to campaign in solidarity with anti-war forces in Russia, and for the freedom of political prisoners such as Boris Kagarlitsky.

- 1

Adam Tooze, Chartbook #209 The Sudan crisis and the Sahel gold rush

- 2

Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, Nuclear Disarmament Ukraine

- 3

Russia GDP, GDP per Capita - Worldometer

- 4

Lenin Collected Works, vol. 23, p. 115-116

- 5

Boris Kagarlitsky, Putin’s war is driven by domestic politics: Interview with Boris Kagarlitsky | Links

- 6

Putin and the tsars, The Guardian