Remains of comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) swooping past the Sun, May 2020. (NASA/NRL/STEREO/Karl Battams)

MICHELLE STARR

20 JULY 2021

A comet that broke apart before it was due to appear in Earth's night sky last year has now nevertheless given us a rare and wonderful gift.

As its disembodied tail continued its journey through the Solar System, a spacecraft orbiting the Sun was able to pass through its tail, quite by chance. The European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter has now given us a unique glimpse into the tail of a disintegrated comet.

The findings have been presented at the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting 2021.

Comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) was discovered in December of 2019, and immediately comet-watchers were excited. Its path around the Sun was expected to take it close enough to Earth to be visible with the naked eye. Before it could get to that point though – and long before its expected perihelion – the comet disintegrated.

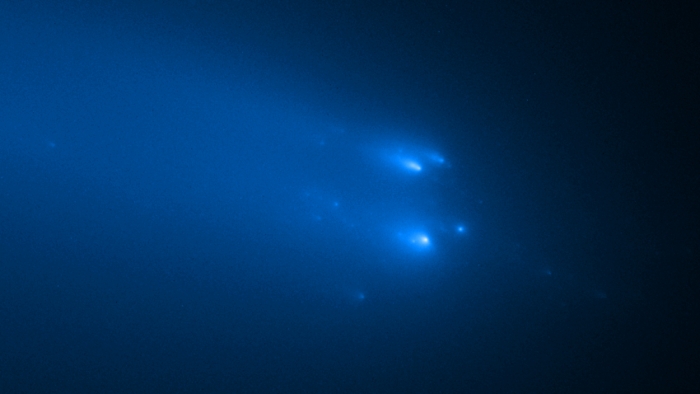

NASA/ESA/STScI/D. Jewitt, UCLA/CC BY 4.0

Above: Hubble Space Telescope image of comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) on April 20 2020, providing the sharpest view to date of the breakup of the solid nucleus of the comet.

In April of last year, images from the Hubble Space Telescope showed the fragments of the comet, shattered as its ices sublimated in the increasing warmth drawing nearer to the Sun. This is not actually an uncommon occurrence, but it did rather dash our hopes of comet-watching.

There were other hopes pinned on C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS), too. Not long after it launched, the Solar Orbiter team noticed that its path would bring it through the comet's tail. The spacecraft wasn't designed for this type of encounter, and nor were its instruments supposed to be switched on at this point, but the scientists figured why not try to see what they could?

When the comet disintegrated, the team figured that, since they had already prepared, they may as well follow through with their plans, even though there might be nothing to detect. However, when Solar Orbiter made its planned rendezvous with the cometary tail, it did indeed detect something.

Now scientists have reconstructed the encounter to learn exactly what the probe detected.

"We have identified a magnetic field structure observed at the beginning of June 4th 2020, associated with a full magnetic field reversal, a local deceleration of the flow and large plasma density, and enhanced dust and energetic ions events," write a team led by physicist Lorenzo Matteini of University College London.

"We interpret this structure as magnetic field draping around a low-field and high-density object, as expected for a cometary magnetotail. Inside and around this large-scale structure, several ion-scale fluctuations are detected that are consistent with small-scale waves and structures generated by cometary pick-up ion instabilities."

In other words, Solar Orbiter's instruments detected the magnetic field of the comet's tail, embedded in the ambient interplanetary magnetic field. This allowed them to learn more about C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS)'s ion tail.

Comets, you see, have two tails. There's the dust tail; that one is made up of dust ejected by the comet as icy material sublimates, generating a dusty atmosphere called a coma around the cometary nucleus. Radiation pressure from the Sun and the solar wind pushes dust away, forming a tail.

The ion tail, on the other hand, is produced when solar ultraviolet light ionizes molecules in the coma. The resulting plasma generates a magnetosphere; it is also pushed away by the solar wind, and that is the ion tail.

The team's results showed that the magnetic field of the ion tail remains for a time after the comet disintegrates. The magnetic field embedded in the solar wind then bends and drapes around the magnetic field of the ion tail.

The probe's measurements, they said, are consistent with an encounter with a cometary magnetic and plasma structure embedded in the solar wind, either associated with a fragment of the broken comet, or a portion of the tail that was previously disconnected.

"This is quite a unique event, and an exciting opportunity for us to study the makeup and structure of comet tails in unprecedented detail," Matteini said.

"Hopefully with the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter now orbiting the Sun closer than ever before, these events may become much more common in future!"

The findings have been presented at the National Astronomy Meeting 2021.

Above: Hubble Space Telescope image of comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) on April 20 2020, providing the sharpest view to date of the breakup of the solid nucleus of the comet.

In April of last year, images from the Hubble Space Telescope showed the fragments of the comet, shattered as its ices sublimated in the increasing warmth drawing nearer to the Sun. This is not actually an uncommon occurrence, but it did rather dash our hopes of comet-watching.

There were other hopes pinned on C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS), too. Not long after it launched, the Solar Orbiter team noticed that its path would bring it through the comet's tail. The spacecraft wasn't designed for this type of encounter, and nor were its instruments supposed to be switched on at this point, but the scientists figured why not try to see what they could?

When the comet disintegrated, the team figured that, since they had already prepared, they may as well follow through with their plans, even though there might be nothing to detect. However, when Solar Orbiter made its planned rendezvous with the cometary tail, it did indeed detect something.

Now scientists have reconstructed the encounter to learn exactly what the probe detected.

"We have identified a magnetic field structure observed at the beginning of June 4th 2020, associated with a full magnetic field reversal, a local deceleration of the flow and large plasma density, and enhanced dust and energetic ions events," write a team led by physicist Lorenzo Matteini of University College London.

"We interpret this structure as magnetic field draping around a low-field and high-density object, as expected for a cometary magnetotail. Inside and around this large-scale structure, several ion-scale fluctuations are detected that are consistent with small-scale waves and structures generated by cometary pick-up ion instabilities."

In other words, Solar Orbiter's instruments detected the magnetic field of the comet's tail, embedded in the ambient interplanetary magnetic field. This allowed them to learn more about C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS)'s ion tail.

Comets, you see, have two tails. There's the dust tail; that one is made up of dust ejected by the comet as icy material sublimates, generating a dusty atmosphere called a coma around the cometary nucleus. Radiation pressure from the Sun and the solar wind pushes dust away, forming a tail.

The ion tail, on the other hand, is produced when solar ultraviolet light ionizes molecules in the coma. The resulting plasma generates a magnetosphere; it is also pushed away by the solar wind, and that is the ion tail.

The team's results showed that the magnetic field of the ion tail remains for a time after the comet disintegrates. The magnetic field embedded in the solar wind then bends and drapes around the magnetic field of the ion tail.

The probe's measurements, they said, are consistent with an encounter with a cometary magnetic and plasma structure embedded in the solar wind, either associated with a fragment of the broken comet, or a portion of the tail that was previously disconnected.

"This is quite a unique event, and an exciting opportunity for us to study the makeup and structure of comet tails in unprecedented detail," Matteini said.

"Hopefully with the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter now orbiting the Sun closer than ever before, these events may become much more common in future!"

The findings have been presented at the National Astronomy Meeting 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment