The revolutionary ambitions of Iran’s Generation Z

Narges, a young Iranian protester, walks confidently through ranks of riot police on her way to work with long, black, wavy hair clearly on show.

In another country her appearance would be unremarkable, but in the Islamic republic which has strict rules about what women can wear in public, it is unthinkable. More unusual still is the response: nothing.

This flagrant defiance of wearing a compulsory hijab in public is becoming a new normal — something women like Narges could not have imagined before the tragic death of Mahsa Amini a month ago.

The 22-year-old Kurdish woman died in the custody of morality police on September 16 after allegedly violating the Islamic dress code. Her death has outraged Iranians and sparked nationwide protests that have, in turn, provoked a heavy-handed, lethal response from the state.

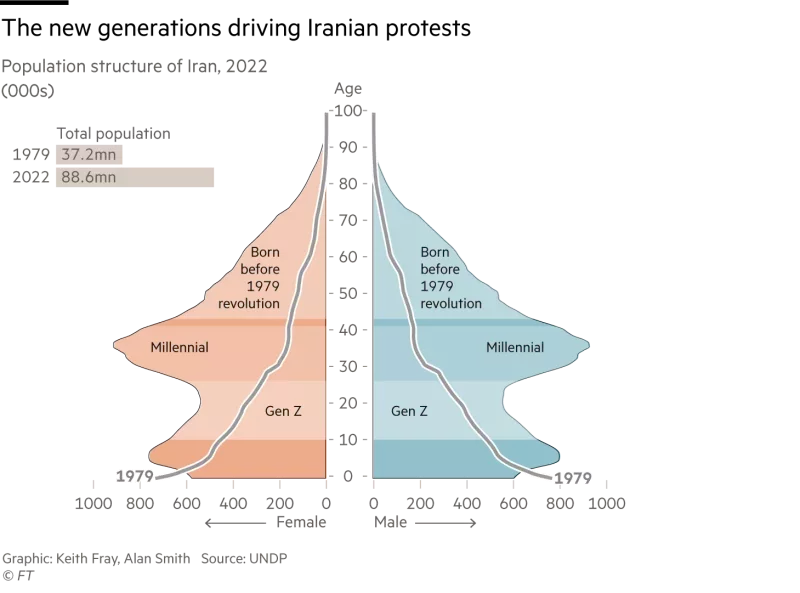

Generation Z has surprised the country — and the world — by refusing to back down during one of the most widespread and long-lasting anti-regime demonstrations in the Islamic republic’s history.

“Woman, life, freedom” has become the battle cry of young men and women in the streets, on university campuses and in schools. Their ultimate goal, protesters say, is to overthrow the Islamic republic in favour of a secular, democratic system, even if the cost is their lives.

They are facing down a regime supported by formidable institutions such as the elite Revolutionary Guards and a multi-layered network of loyalists and businessmen whose interests depend on a continuation of the status quo.

Nonetheless, the protests are a serious warning to Iran’s rulers that they are grappling with a different generation, many of whom do not relate to the regime’s ideology and are furious about being deprived of the everyday freedoms and opportunities afforded to their international peers.

Their movement has the potential to inspire more demonstrations and strikes as a cost of living crisis deepens, posing one of the most significant threats to the Islamic republic’s 43-year dominance.

Top leaders — at least publicly — dismiss the idea that the anti-regime protests are a historic turning point and are showing no signs of making any structural or constitutional concessions. Analysts do not expect the regime to rethink a supreme leader as ultimate authority, its hostility towards the US, flexing muscles in the Middle East, or expansion of the nuclear programme.

Protesters, who have radical ambitions for their country’s future, say that the time for knee-jerk political gestures has run out. The impasse has many Iranians worried about difficult days ahead.

The stand-off has repercussions for the country’s long-term stability. In a joint statement, five prominent economists have likened the growing chorus for change to “a flood which has been roaring but has suddenly faced a deadlock”. They say the choice facing political leaders is either to clear the way or let the floodgates burst and unleash a torrent of disruption.

Extensive poverty, corruption of those linked to the regime and declining political participation in recent years have all weakened social capital and fostered a sense of hopelessness, the economists say. In addition, Iranian families’ welfare has, on average, declined by 37 per cent over the past decade, causing the middle class to shrink.

Narges, 27, says it is this gloomy picture that makes her generation’s fight inevitable: the prosperous future she dreams of, one full of fun and pleasure, cannot be achieved living under theocracy.

“I do value going out without a hijab and the regime’s forces completely ignore me while passers-by say ‘bravo’ to women like me”, she says. “But this system has inflicted irreparable damage to us from our childhood. Only its collapse can help us end inequalities between men and women and have freedom for the most basic, normal things”.

Generation Unrest

Iran has long had a robust protest culture; a symptom of the country’s internal struggle to transition from a traditional society to a modern one.

Its contemporary history has been shaped by regular pockets of social unrest and several uprisings including two revolutions — a constitutional one more than a century ago and the 1979 Islamic revolution.

A slow shift towards greater modernity and more progress for women has become more urgent as a new generation grows impatient. The last national census six years ago showed those aged between 10 to 24 years old make up about 22 per cent of the population of 80mn. Their values contrast sharply with those of Iran’s ageing yet determined leaders, some of whom are in their nineties.

An increasingly educated population, including women who occupy about 60 per cent of university places, fast-paced urban development and wider access to the internet and smartphones, have raised public expectations.

Young people want fair and transparent government, better welfare, decent jobs as well as the ability to travel abroad and enjoy a healthy sex life — not necessarily within marriage.

Iran’s Generation Z, who have grown up with the internet and satellite television, say the things they are fighting for are incompatible with a system that demands an Islamic lifestyle; early marriage, more children and defending one’s religion against threats. Protecting these values, however, is essential for the regime to satisfy millions of zealous loyalists in Iran and the Middle East who represent one of its main pillars of power.

Major General Mohammad Bagheri, Iran’s chief of staff for the armed forces, has warned his military commanders that “traditional approaches will not work anymore” if it wants to foil threats to power such as those fuelled by social media. He positioned the protest movement as part of a wider battle against foreign influence.

“Today, we are facing multiple military, cultural, newly emerged and sometimes unknown threats from the enemy targeting us either simultaneously or in thoughtful combinations”, he said. “We have to be ready for . . . a hybrid warfare which is extraordinarily heavy and complicated work for us and armed forces’ commanders”.

Ahmad Zeidabadi, a reformist political analyst and a former political prisoner, said in an interview with the semi-official ILNA news agency that “part of the system thinks power, dignity and wealth belongs to insiders and its loyalists . . . while the rest of the people have no rights such as establishing political parties, running for elections and taking part in decision making and hence they have no right to protest”.

It is this political order that protesters are pushing back against, many of whom come from the urban middle class who, until recently, were widely regarded across society as spoiled and pampered by their privileged, educated families.

Now they stand in front of riot police showing no fear of being killed. Over the past month, more than 40 protesters have died, according to state television. Amnesty International says 144 men, women and children have lost their lives, including 20 teenage boys and 3 girls.

Bijan Abdolkarimi, a professor of philosophy at Islamic Azad University, says the failure to understand this country’s youth is a mis-step. “This generation is rebellious and accepts no one else’s authority be it a father’s at home, or teachers’ at school or university”, he told the reformist Etemad daily newspaper. “It doesn’t accept men’s authority over women and . . . fights with tradition and questions all its principles . . . The worst way to deal with them is police, military and security approaches”.

Anger piles up

Dissent, however, is not limited to the younger generation. There have been at least three other major protests since 2009 led by the middle and working classes in which hundreds were killed. Protests involving farmers, teachers, pensioners and workers have been frequent.

The latest crisis follows decades of disappointment in successive political leaders to deliver change. Political reforms initiated in 1997 by Mohammad Khatami, then president, were met with resistance from hardliners. Later, centrist president Hassan Rouhani promised a more functioning economy under a nuclear deal that his government signed with world powers in 2015. The deal collapsed in 2018 when the US, under the Trump administration, pulled out.

The election of hardliner Ebrahim Raisi as president last year marked a new low. Turnout was 48.8 per cent — one of the poorest on record after main rivals were not allowed to run. This was the moment pro-democracy groups say the road to any reforms hit a dead end.

Mehdi Behabadi, head of semi-official ISPA opinion poll centre, says “a considerable majority” of Iranians harbour “anger” towards the Islamic republic “a factor which is at a dangerous level”. The average age of protesters is also getting younger, he adds, and includes those under 20 years old, while the number of women protesters is “very close” to men.

“Every time there has been widespread protests, they subside only superficially while the anger piles up increasing the level of violence [next time]”, he says.

Behabadi also believes the number of demonstrators in recent years is only “a tiny percentage of all those who are angry” because many believe that history has shown the risk of participation outweighs the reward.

Aila, a 19-year-old computer engineering student, is sympathetic but has chosen not to join protests at her university. “I’d like to see the Islamic republic gone as I see no future for myself in my homeland with all the injustice, gender discrimination, gloomy economic perspective and waste of talents”, she says. “But I don’t see an option for a successor and surely don’t want to see insecurity that the absence of an established government can bring”.

Iran’s leaders are encouraged that the protests have not yet snowballed into mass demonstrations. Labourers have held some sporadic strikes, but teachers, farmers, businessmen and the pious masses, including mid-ranking clergy, are largely in a wait-and-see mood.

Meanwhile, Iranians overseas are urging silent supporters to rise up, organising demonstrations in western capitals and lobbying for international backing. But this disparate opposition is not seen as a viable alternative to the regime, partly because they are far from unified themselves.

It is for this reason that a regime insider close to hardline forces says the protests are not seen as an immediate threat to the Islamic republic.

“Protesters are not from a political party, they don’t have a leader. They are not ideologically motivated to die for their causes. As soon as they get arrested, they express regret”, he says. “Iran’s opposition overseas is no threat. Can they all get together and have one charismatic leader like Imam [Ruhollah] Khomeini to take out millions of supporters on to the streets [as happened in the 1979 revolution]? No”.

The insider adds there will be no significant concessions beyond measures such as an unspoken and relaxed approach to wearing hijabs in public.

But with the unrest and brutal crackdowns playing out on platforms like Instagram and WhatsApp thanks to tech-savvy protesters who use VPNs to circumvent bans on social media, analysts say the republic is losing the media war and is being discredited at home and abroad.

The overseas opposition also uses foreign-based and foreign-funded satellite television to convince Iranians that a revolution is in the making and that a united front can finally bring down 43 years of the Islamic republic.

Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the target of slogans such as “death to the dictator”, denies the dissent is homegrown and instead has blamed external players including the US, Israel and Saudi Arabia. “The only solution is to resist”, he says.

For many Iranians, his response underlines how out of touch the regime is. Shahla, a housewife and mother of two teenage boys, says the main reason she protests is because the political system shows too little leniency towards ordinary people.

“What I hate the most is that the Islamic republic protects the most junior members of its loyalists but is so tough on us”, she says. “Why is it a problem to say one individual made a mistake in the case of Amini and apologise?”

A regime under pressure

Although analysts say those at the top of Iran’s political system remain united in how to deal with the discontent, another regime insider says those at the mid-level are unhappy at seeing young protesters being killed and think the response has gone too far.

They believe, he says, that the regime should listen to protesters and take actions while the 83-year-old Ayatollah Khamenei is alive.

His death — and the rumoured succession of his second son, Mojtaba — could make any reforms far more complicated or near impossible, he adds, because protesters have made clear they will not accept him.

Protesters meanwhile see no benefit in talking with the authorities. Moein, a 23-year-old history student, says the Islamic republic has no intention to change its structures of power. “People from a motorcycle delivery man to a doctor have reached a stage where they don’t want to give up on their demands which are equal rights for men and women and freedom”, he says.

Even if protests are suppressed, he adds, “we shall see bigger protests in the future as these demands will not disappear”.

Analysts agree. “The pent-up political demands . . . are now manifested in non-controversial, inclusive slogans such as ‘woman, life, freedom’”, says Saeed Hajjarian, a strategist for reformists. “This shows the centre of gravity of the society’s demands has shifted from politics to citizens’ rights . . . for all social classes rather than only the urban middle class”.

Iran’s hardliners warn that the continuation of protests is putting Iran’s territorial integrity at risk and could embolden separatists to fight the central government in a country which includes ethnicities such as Arabs, Kurds, Baluchis, Turks and Sunni Muslims.

While protests in Iranian Kurdistan have intensified since Amini’s death, people in the city of Zahedan, home to ethnic Baluchis and Sunnis, have separately clashed with the authorities after a 15-year-old girl was allegedly raped by a senior police official. Amnesty estimates at least 82 were killed, but officials put deaths at 19.

Pushback against the regime protests also coincides with renewed calls from politicians to sign a nuclear deal with the Biden administration and put an end to US sanctions on Iran’s oil and banking sectors. A lack of movement on the deal is fuelling public frustration as inflation reaches 42.1 per cent and the youth unemployment rate climbs to 23 per cent.

Nuclear talks remain deadlocked after Washington and Tehran failed to agree on the most recent draft proposed by the EU, the mediator in those negotiations. Diplomats and analysts do not expect any progress until after the US midterms in November.

Some politicians say securing a deal is vital to help quell discontent. Ali Larijani, a former conservative Speaker of parliament, says: “The sooner this problem is resolved the more it is to the benefit of the Islamic republic. People should not be under this much pressure”.

Narges, a trained IT engineer, is working as an accountant and earns a monthly salary of about $250 which barely covers her daily expenses. She envies the lives of the young people and teenagers in other countries that she obsessively follows on YouTube.

“I feel that not only have I never experienced the pleasures of teenagers in the US, Britain, Australia, I cannot use my own creativity and talent to have a decent salary and be hopeful about my future”, she says.

The only option, she says, is to continue protesting “until we defeat the Islamic republic even though I’m aware the system is frightening and vengeful”.

By Najmeh Bozorgmehr.

Voices: ‘Iranian women aren’t sleeping’:

This is what it’s like being a woman in

Iran right now

I am an Iranian writer who was born after the 1979 revolution. I live in Tehran. Like Mahsa Amini and other women, I have been arrested many times on the street for not wearing a hijab and have suffered the brutal behavior of police.

Since I was six years old, I have been ordered to remain silent and not question the wearing of the hijab in girls’ schools. When I was a child, my mother and aunt were detained in front of my eyes on the street for hijab “offences” and kept in jail for a night.

The murder of Mahsa Amini has shocked us all. And it has made me think about how we got here – and what we need to do now to get out.

After the 1979 revolution in Iran, a radical Shia government came to power, which claims to be able to run society based on the laws of Islam 1,400 years ago. It relies on reactionary Shari’a rulings, some of which involve mandatory restrictions on women. According to the Islamic laws, the woman is considered the man’s land; part of his property. A man can give her commands and prohibitions, just like a pet.

A large number of women who protested in 1979 were killed or imprisoned or fled from Iran. This new regime, with its restrictions on women’s clothing and situation, established from that point that a woman’s body was in fact the property of the “authorities”.

With laws such as stoning and flogging women in public, and other medieval performances, the new regime managed to make it clear that women are to be used to keep the rest of society silent. In other words, by conquering and encroaching on women as property – by punishing her – the regime can show off its power.

Iranian women are protesting against the violation of our rights, but it’s not just restricted to our clothing. Here is what else is at stake:

A woman’s testimony in court is counted as half of a man’s. If a witness is needed to prove a crime, two women have to testify so that they have testified as much as one man.

Women do not have the right to enter stadiums to watch sports (Sahar Khodayari died in protest at a jail sentence for going to watch a football match).

Women do not have the right to dance and sing; or the right to abortion. The punishment for abortion is equal to killing a living human being.

A woman cannot be a court judge. A woman cannot divorce her husband – this right belongs to the man only. He can divorce his wife whenever he wants.

A woman does not have the right to custody of a child after divorce. The child belongs to the father.

A woman does not have the right to leave the country. This right belongs to the father until the age of 18, and after marriage, it belongs to the husband.

A woman is forced to wear a full hijab during sport competitions. Many female athletes have been fired from the national team and some of them play for the national team of other countries.

Our fathers and brothers have the right to kill us, and because (according to the Islamic Penal Code), fathers and husband are considered guardians, they will not be punished for doing so.

And recently, the ban on women eating ice-cream in public spaces was proposed, but not enforced.

In the best of circumstances, a woman’s legal rights are half of a man’s. But the important question remains: how is it fair that a being who is considered half a man when it comes to her everyday rights, can still be seen as a complete person in front of the ballot boxes? A woman is only considered a full person when we are being used to confirm the pillars of power. This is the ultimate hypocrisy. Maybe now the world will understand why women are standing on the frontline of these protests.

Perhaps you’re also wondering why men are protesting with us – I think I can tell you. The fact is that the domination over the female body (as a perfect example of a “subordinate citizen”) has also seen the state’s domination over other parts of Iranian society; including men.

After the 1979 revolution, men saw that while they may have rights towards their wives, daughters and sisters, they did not have many rights for themselves against the power of the government. They are, even now, considered “nothing” against the mighty will of those in charge.

Many men came to the conclusion that every time they took a right from a woman, they legitimised the law of domination over all of those the government views as subordinate. For regardless of gender, we are all inferior in front of the authority of the law. And anyone who questions those in power is considered an “infidel”. The punishment for being an infidel in the eyes of the law is death, whipping or prison.

In this way, fighting against the laws that prohibit women is the first step to fighting for freedom for all people in Iran.

You may also have wondered why some Iranian women continue to wear the hijab in the streets; even if we don’t believe in Islam. Well, that is easy – it is because anyone who declares that they don’t believe in Islam will either be killed or deprived of education and employment. Many who feel this way are forced to emigrate, even if we love our country.

This is what is truly at stake when you see our protests and when you watch footage of us removing the hijab. And it’s important to remember that when you see Iranian women on social media without headscarves – or at a party, while drinking and dancing – it still does not indicate our freedom or liberty. No:,every single Iranian woman who does this, does so in civil protest. We do it at tremendous risk. We do it to fight for freedom.

It is from the heart of living under such suffocation that the slogan “woman, life, freedom” was born. Maybe, after reading this text, you can imagine what a great achievement such a slogan is.

Iranian women have not been sleeping since Mahsa Amini was killed. We have seen that it is the time to announce our awakening. Many people are being killed in the streets of Iran these days. Many women who removed the hijab are in prisons. If you see Iranians in the streets of your city today, please know that we are not without a country – but we have had to flee.

This fragmented diaspora that shouts the name of its homeland in your homeland no longer wants to be treated as a half-being. Our goal is to have the right to our own bodies. This movement is the biggest feminist revolution in the world – and the world stands with us, because it knows that the outcome will be our biggest achievement, together.

Guest column: Iran’s current uprising places regime change well within reach

Ben Janloo

Sun, October 16, 2022

Whenever unrest sparks in Iran, I suffer for my friends and family still living under the mullahs, yet I am also hopeful that the Iranian people will finally achieve victory over their oppressors. This has perhaps never been truer than in these last few weeks, as protests over the death of Mahsa Amini at the hands of the “morality police” keep escalating.

The protests began after her funeral in Kurdistan but have since spread to over 150 cities. As with previous uprisings, the spread has been fueled in part by a broad political message showing the vast demand for a regime change.

Because of the violence that Mahsa endured due to her resistance, the initial focus was women’s rights, but the relevant issues proved to be inseparable from the general ideological divide between the mullahs and the Iranian people. Women have been chanting slogans such as “Down with Khamenei (the regime’s Supreme Leader)” and “Death to the Dictator.”

The use of these slogans across the protests shows the organized nature of the uprising, more than its predecessors in the last five years. In early 2018, even Supreme Leader Khamenei admitted that the leading opposition group, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (MEK/PMOI), played a role in promoting unrest.

The MEK has continuously pushed the Iranian people toward uprisings, with regime change as its ultimate goal. Its resistance units inside Iran keep information about the domestic situation flowing out, even when the regime has tightened its control over the internet in efforts to crackdown on anti-government sentiment.

I am thankful for the MEK as they provide information far more complete than what reaches mainstream media. Of course, this adds to anxious thoughts, as they provide accurate numbers on death tolls and arrests, which are far more than the regime claims.

However, the MEK underscores the sheer intensity of the ongoing uprisings. My acquaintances in Iran also underscore the same, sharing my hope that this uprising is the one that leads to the overthrow of the mullahs.

On Sept. 28, Sens. James Lankford (R-OK) and Chris Coons (D-DE) introduced a bipartisan resolution condemning Mahsa Amini’s death and calling for an end to the systemic persecution of women in Iran. I hope that this view is widely shared by Western politicians and their constituents, who should recognize that the overthrow of the mullahs benefits global security.

Unfortunately, the international community does not seem to fully recognize the potential of the uprisings. Moreso, this creates a space for the regime to step up its crackdowns before the movement can achieve its aims.

Public statements by Western governments must become louder and more frequent if they are truly committed to preventing further oppression. It must be made absolutely clear that the Iranian people have an inherent right to defend themselves by any available means, and that regime change from within is a well-justified and appropriate aim for their movement.

The goal is achievable, but the international community has a role in determining the price Iranians will pay for it.

Ben Janloo is a business owner living in Oklahoma City and president of the Iranian-American Community of Oklahoma.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Iran’s current uprising places regime change well within reach

Oklahoma professor: Iran's struggle for democracy has a long history

Afshin Marashi

Sun, October 16, 2022

The death of the 22-year-old Iranian-Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini at the hands of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s morality police has sparked ongoing protests. In courageous acts of protest, Iranian women are marching in the streets, burning their state-mandated Islamic headscarves, and chanting: “Women, Life, Freedom.” These are unprecedented acts of defiance in the history of the Islamic Republic.

A protester holds a placard during a demonstration in support of Kurdish Iranian woman Mahsa Amini during a protest on Oct. 3, 2022, in Nantes, western France, following her death in Iran. - Amini, 22, died in custody on Sept. 16, 2022, three days after her arrest by the notorious morality police in Tehran for allegedly breaching the Islamic republic's strict dress code for women. in Nantes, western France on Sept. 29, 2022.

For those unfamiliar with Iranian history, it would be easy to see the current protests as narrowly contained to current circumstances. In fact, these protests are part of a longer history of struggle for democracy in modern Iran.

As early as 1905, Iran was the first place in the Middle East to experience a revolutionary movement seeking a democratic form of government. In the short term, the “Constitutional Revolution” was defeated by both internal divisions and external interventions.

However, Iran’s democratic aspirations were not extinguished. After three decades of royalist absolutism and foreign occupation, the 1940s witnessed the new growth of political parties, a vibrant Iranian press, and new educational opportunities that empowered citizens from all walks of life, especially women.

This era culminated with the rise of Mohammad Mossadegh, the prime minister who rallied the democratic will of the Iranian people to nationalize the British-controlled Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. The fear that communism was lurking within Mossadegh’s broad-based democratic coalition, led the American CIA and the British MI6 to foment internal unrest leading to the coup d’état of August 1953 that overthrew Mossadegh.

The next 25 years of Iranian history are a contradiction. The newly restored shah ruled with an iron fist and limited political freedoms. At the same time, however, Iranians made remarkable social progress during this era. Iranian women gained the right to vote in 1963 — by royal decree — over the objection of the clerics. Reforms to family law were also initiated in 1967 and 1975, granting women rights in marriage, divorce and the custody of children, also over the objections of religious authorities.

These social reforms so empowered Iranian women that by the time of the revolution of 1979 Iranian women joined the struggle against the shah’s autocracy.

It is forgotten today, but the revolution that toppled the monarchy in January 1979 did not begin as an “Islamic Revolution.” The initial revolutionary spark began, not in 1979, but in 1977, and was led by democracy advocates. Their initial demands included the release of political prisoners and the guarantee of free elections.

These Iranian calls for democracy in 1977 were inspired by an already well-established democratic tradition within Iran. By 1978, however, the course of Iran’s revolutionary process took unpredictable turns, and advocates for democracy quickly found themselves outmaneuvered. In the emotional context of the revolutionary struggle, liberal calls for civil rights and free elections seemed insufficiently revolutionary.

After the fall of the shah, Iranian democracy was once again thwarted, this time by the emerging authoritarianism of the Islamic Republic. Women lost many of the social rights that they had gained in the previous decades, including the right to choose for themselves to wear the Islamic headscarf.

In the years since, calls for democratic reform have not disappeared inside Iran. The failure of successive waves of reform, such as the presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) and the Green Movement of 2009, revealed the deep structural obstacles to working within the Islamic Republic’s political system.

As we have seen during the past weeks in Iran, this newest generation of advocates for Iranian democracy are no longer satisfied with working within the system and are demanding fundamental changes to Iran’s form of government.

How this process will unfold in the weeks and months to come is unknown.

What is known is that this newest effort to build a democratic Iran is the product of more than a century of struggle. It is an enduring struggle that deserves our support and promises to rewrite the history of modern Iran and its relationship with the United States.

Afshin Marashi is a professor and the Farzaneh Family Chair in Modern Iranian History at the University of Oklahoma's College of International Studies.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Oklahoma professor: Iran's struggle for democracy has a long history