SPACE/COSMOS

What happened before the Big Bang?

A computational method may provide answers to cosmic mysteries about the origin of the universe

image:

Complex computational methods could solve cosmic mysteries.

view moreCredit: Gabriel Fitzpatrick for FQxI, © FQxI (2025)

We’re often told it is “unscientific” or “meaningless” to ask what happened before the big bang. But a new paper by FQxI cosmologist Eugene Lim, of King's College London, UK, and astrophysicists Katy Clough, of Queen Mary University of London, UK, and Josu Aurrekoetxea, at Oxford University, UK, published in Living Reviews in Relativity, in June 2025, proposes a way forward: using complex computer simulations to numerically (rather than exactly) solve Einstein’s equations for gravity in extreme situations. The team argues that numerical relativity should be applied increasingly in cosmology to probe some of the universe’s biggest questions–including what happened before the big bang, whether we live in a multiverse, if our universe has collided with a neighboring cosmos, or whether our universe cycled through a series of bangs and crunches.

Einstein’s equations of general relativity describe gravity and the motion of cosmic objects. But wind the clock back far enough and you’ll typically encounter a singularity–a state of infinite density and temperature–where the laws of physics collapse. Cosmologists simply cannot solve Einstein’s equations in such extreme environments–their normal simplifying assumptions no longer hold. And the same impasse applies to objects involving singularities or extreme gravity, such as black holes.

One issue might be what cosmologists take for granted. They normally assume that the universe is ‘isotropic’ and ‘homogeneous’–looking the same in every direction to every observer. This is a very good approximation for the universe we see around us, and one that makes it possible to easily solve Einstein’s equations in most cosmic scenarios. But is this a good approximation for the universe during the big bang?

“You can search around the lamppost, but you can’t go far beyond the lamppost, where it’s dark–you just can’t solve those equations,” explains Lim. “Numerical relativity allows you to explore regions away from the lamppost.”

Beyond the Lamppost

Numerical relativity was first suggested in the 1960s and 1970s to try to work out what kinds of gravitational waves (ripples in the fabric of spacetime) would be emitted if black holes collided and merged. This is an extreme scenario for which it is impossible to solve Einstein’s equations with paper and pen alone–sophisticated computer code and numerical approximations are required. Its development received renewed focus when the LIGO experiment was proposed in the 80s, although the problem was only solved in this way in 2005, raising hopes that the method could also be successfully applied to other puzzles.

“You can search around the lamppost, but you can’t go far beyond the lamppost, where it’s dark–you just can’t solve those equations. Numerical relativity allows you to explore regions away from the lamppost,” says Eugene Lim.

One longstanding puzzle that Lim is particularly excited about is cosmic inflation, a period of extremely rapid expansion in the early universe. Inflation was initially proposed to explain why the universe looks the way it does today, stretching out an initially small patch, so that the universe looks similar across a vast expanse. “If you don't have inflation, a lot of things fall apart,” explains Lim. But while inflation helps explain the state of the universe today, nobody has been able to explain how or why the baby universe had this sudden short-lived growth spurt.

The trouble is, to probe this using Einstein’s equations, cosmologists have to assume that the universe was homogeneous and isotropic in the first place–something which inflation was meant to explain. If you instead assume it started out in another state, then “you don't have the symmetry to write down your equations easily,” explains Lim.

But numerical relativity could help us get around this problem–allowing radically different starting conditions. It isn’t a simple puzzle to solve, though, as there’s an infinite number of ways spacetime could have been before inflation. Lim is therefore hoping to use numerical relativity to test the predictions coming from more fundamental theories that generate inflation, such as string theory.

Cosmic Strings, Colliding Universes

There are other exciting prospects, too. Physicists could use numerical relativity to try to work out what kind of gravitational waves could be generated by hypothetical objects called cosmic strings–long, thin “scars” in spacetime–potentially helping to confirm their existence. They might also be able to predict signatures, or “bruises,” on the sky from our universe colliding with neighboring universes (if they even exist), which could help us verify the multiverse theory.

Excitingly, numerical relativity could also help reveal whether there was a universe before the big bang. Perhaps the cosmos is cyclic and goes though “bounces” from old universes into new ones–experiencing repeated rebirths, big bangs and big crunches. That’s a very hard problem to solve analytically. “Bouncing universes are an excellent example, because they reach strong gravity where you can’t rely on your symmetries,” says Lim. “Several groups are already working on them–it used to be that nobody was.”

Numerical relativity simulations are so complex that they require supercomputers to run. As the technology of these machines improves, we might expect significant improvement in our understanding of the universe. Lim is hoping the team’s new paper, which outlines the methods and benefits of numerical relativity, can ultimately help get researchers across different areas up to speed.

“We hope to actually develop that overlap between cosmology and numerical relativity so that numerical relativists who are interested in using their techniques to explore cosmological problems can go ahead and do it,” Lim says, adding, "and cosmologists who are interested in solving some of the questions they cannot solve, can use numerical relativity.”

Journal reference, Living Reviews in Relativity: Cosmology using numerical relativity

ABOUT FQxI

The Foundational Questions Institute, FQxI, catalyzes, supports, and disseminates research on questions at the foundations of science, particularly new frontiers in physics and innovative ideas integral to a deep understanding of reality but unlikely to be supported by conventional funding sources. Visit FQxI.org for more information.

Journal

Living Reviews in Relativity

Method of Research

Literature review

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Cosmology using numerical relativity

XRISM unveils hot gas and its dynamic activity around a black hole in the faintest state

Ehime University

image:

The strong gravity of the black hole (shown as a small black dot at the center of the disk on the right) pulls gas from the companion star (left). As the gas spirals inward, it forms a high-temperature accretion disk around the black hole.

view moreCredit: JAXA

An international research team led by Professor Jon M. Miller (University of Michigan), Dr. Misaki Mizumoto (University of Teacher Education Fukuoka), and Dr. Megumi Shidatsu (Ehime University) has reported remarkable findings from a XRISM observation of the black hole X-ray binary 4U 1630-472, located in our galaxy. XRISM is an X-ray astronomy satellite developed by Japan in collaboration with the United States and Europe and was launched from the Tanegashima Space Center on September 7, 2023. This observation, conducted during the fading end of an outburst, successfully captured the highly ionized iron absorption lines at the system’s faintest X-ray state. The results offer a rare glimpse into the structure and motion of hot gas around a black hole during its faintest X-ray phase, providing new insights into how these extreme systems evolve and interact with their surroundings.

Black holes range in size from a few to billions of solar masses. A black hole X-ray binary contains a stellar-mass black hole, typically less than a few ten times the solar mass, orbiting a normal star. Gas drawn from the companion star spirals toward the black hole, forming an extremely hot accretion disk. In its inner regions, temperatures can reach nearly 10 million Kelvin, generating intense X-ray emission.

About 100 confirmed or candidate black hole X-ray binaries are known, including the famous Cygnus X-1. These systems spend most of their time in a dim state, but occasionally undergo outbursts, during which their X-ray brightness can increase by factors of 10,000 in just about a week. During such episodes, some systems launch powerful winds from their accretion disks, yet the conditions that trigger such large outbursts and launch winds remain poorly understood.

Studying these stellar-mass black holes also offers valuable insights into the behavior of supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies, which can profoundly influence star formation and galactic evolution. By observing stellar-mass black holes up close, astronomers aim to reveal universal processes that shape cosmic environments.

XRISM carries Resolve, a cutting-edge soft X-ray spectrometer capable of measuring X-ray energies with unprecedented precision. Shortly after the start of the regular operations, the team observed 4U 1630-472, a black hole X-ray binary located in the constellation Norma. Over roughly 25 hours from February 16–17, 2024, XRISM caught the system just before it returned to quiescence at the tail end of an outburst, when its X-ray brightness had already dropped to about one-tenth of its peak.

Observing transient phenomena required rapid coordination. The team conducted daily monitoring of black hole X-ray binaries daily using wide-field X-ray instruments, then worked closely with XRISM’s operations team to adjust the schedule at short notice, making this observation possible.

The resulting spectra revealed clear absorption lines from highly ionized iron, even at this dim stage. Notably, in the latter half of the observation, the absorption strengthened despite little change in the X-ray brightness. Analysis showed that the absorbing gas resided in the outer accretion disk, moving at less than ~200 km/s—much slower than the ~1000 km/s winds observed in brighter phases. At such low speeds, the gas remains gravitationally bound to the black hole. The increase in absorption during the latter half of the observation likely came from a localized gas cloud at the disk’s outer edge, possibly formed where the infalling stream from the companion star collided with the disk.

These observations mark the first time that detailed absorption features have been resolved in a black hole X-ray binary at such low luminosity. Thanks to XRISM’s exceptional spectral capabilities, astronomers were able to map the motion and distribution of hot gas near the black hole in a regime that had previously been beyond reach.

The results show that even when the X-ray output is weak, highly ionized gas can be present—and maybe in motion—around the black hole. This provides valuable insights into the inflow and outflow of gas in the accretion disk and the physical conditions that could trigger wind formation.

These results indicate that, in the faint state observed here, the high-temperature gas is not escaping the system as a wind. However, in brighter states, 4U 1630-472 has been seen launching powerful, high-speed outflows, raising key questions:

- What exact conditions in luminosity and disk structure trigger the acceleration of gas into fast winds?

- How much mass and energy do such winds inject into their surroundings?

The team’s next goal is to catch future outbursts at different brightness levels with XRISM, enabling them to track how the gas properties change over time. They are now on standby, ready to respond swiftly when the next eruption from a black hole X-ray binary occurs.

The red spectrum has been shifted downward for ease of comparison (the X-ray intensity has been reduced to approximately 60% of the actual value). In reality, it is almost identical to the blue spectrum except for the absorption lines.

During the observation, ionized gas located approximately 10,000 km from the black hole is thought to be distributed above the accretion disk. In addition, where gas falling from the companion star impacts the accretion disk, ionized gas clumps form perpendicular to the disk plane due to the collision. In the latter half of the observation period, these clumps move into alignment with the binary’s orbital motion along our line of sight, increasing the X-ray absorption and resulting in deeper absorption lines.

CreditJAXA

Journal

The Astrophysical Journal Letters

First-of-its-kind supernova reveals innerworkings of a dying star

Newly discovered supernova is ‘stripped down to the bone’ to reveal heavier elements

image:

SN 2021yfj is a new kind of supernova, challenging our understanding of stellar evolution. Its progenitor lost its outer shells well before the supernova happened and only consisted of its oxygen/silicon core — unlike any known star in the Milky Way. The dying, stripped-to-the-bone star experienced extreme mass loss episodes that led to the ejecting of material rich in silicon (grey), sulfur (yellow) and argon (purple).

view moreCredit: W.M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko

An international team of scientists, led by Northwestern University astrophysicists, has detected a never-before-seen type of exploding star, or supernova, that is rich with silicon, sulfur and argon.

When massive stars explode, astrophysicists typically find strong signatures of light elements, such as hydrogen and helium. But the newly discovered supernova, dubbed SN2021yfj, displayed a startling different chemical signature.

Astronomers long have theorized that massive stars have a layered structure, similar to an onion. The outermost layers predominantly comprise the lightest elements. As the layers move inward, the elements become heavier and heavier until reaching the innermost iron core.

The observations of SN2021yfj suggest the massive star somehow lost its outer hydrogen, helium and carbon layers — exposing the inner silicon and sulfur-rich layers — before exploding. This finding offers direct evidence of the long-theorized inner layered structure of stellar giants and provides an unprecedented glimpse inside a massive star’s deep interior — moments before its explosive death.

The study will be published on Wednesday (Aug. 20) in the journal Nature.

“This is the first time we have seen a star that was essentially stripped to the bone,” said Northwestern’s Steve Schulze, who led the study. “It shows us how stars are structured and proves that stars can lose a lot of material before they explode. Not only can they lose their outermost layers, but they can be completely stripped all the way down and still produce a brilliant explosion that we can observe from very, very far distances.”

“This event quite literally looks like nothing anyone has ever seen before,” added Northwestern’s Adam Miller, a senior author on the study. “It was almost so weird that we thought maybe we didn’t observe the correct object. This star is telling us that our ideas and theories for how stars evolve are too narrow. It’s not that our textbooks are incorrect, but they clearly do not fully capture everything produced in nature. There must be more exotic pathways for a massive star to end its life that we hadn’t considered.”

An expert on astronomy’s most extreme transient objects, Schulze is a research associate at Northwestern’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA). Miller is an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and a leading member of CIERA and the NSF-Simons AI Institute for the Sky.

A hot, burning onion

Weighing in at 10 to 100 times heavier than our sun, massive stars are powered by nuclear fusion. In that process, intense pressure and extreme heat in the stellar core cause lighter elements to fuse together, generating heavier elements. When the temperature and density increase in the core, burning begins in the outer layers. As the star evolves over time, successively heavier elements are burned in the core, while lighter elements are burned in a series of shells surrounding the core. This process continues, eventually leading to a core of iron. When the iron core collapses, it triggers a supernova or forms a black hole.

Although massive stars typically shed layers before exploding, SN2021yfj ejected far more material than scientists had ever previously detected. Other observations of “stripped stars” have revealed layers of helium or carbon and oxygen — exposed after the outer hydrogen envelope was lost. But astrophysicists had never glimpsed anything deeper than that — hinting that something extremely violent and extraordinary must be at play.

Chasing down a cosmic oddity

Schulze and their team discovered SN2021yfj in September 2021, using Northwestern’s access to the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF). Located just east of San Diego, ZTF uses a wide-field camera to scan the entire visible night sky. Since its launch, ZTF has become the world’s primary discovery engine for astronomical transients — fleeting phenomena like supernovae that flare up suddenly and then quickly fade.

After looking through ZTF data, Schulze spotted an extremely luminous object in a star-forming region located 2.2 billion light-years from Earth.

To gain more information about the mysterious object, the team wanted to obtain its spectrum, which breaks down dispersed light into component colors. Each color represents a different element. So, by analyzing a supernova’s spectrum, scientists can uncover which elements are present in the explosion.

Although Schulze immediately leapt into action, their spectrum search hit multiple dead ends. Telescopes around the globe were either unavailable or could not see through the clouds to obtain a clear image. Luckily, the team received a surprise from an astronomy colleague, who gathered a spectrum using instruments at the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawai‘i.

“We thought we had fully lost our opportunity to obtain these observations,” said Miller. “So, we went to bed disappointed. But the next morning, a colleague at UC Berkeley unexpectedly provided a spectrum. Without that spectrum we may have never realized that this was a strange and unusual explosion.”

“We saw an interesting explosion, but we had no idea what it was,” Schulze said of SN2021yfj. “Almost instantly, we realized it was something we had never seen before, so we needed to study it with all available resources.”

‘Something very violent must have happened’

Instead of typical helium, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen — found in other stripped supernovae — the spectrum was dominated by strong signals of silicon, sulfur and argon. Nuclear fusion produces these heavier elements within a massive star’s deep interior during its final stages of life.

“This star lost most of the material that it produced throughout its lifetime,” Schulze said. “So, we could only see the material formed during the months right before its explosion. Something very violent must have happened to cause that.”

While the precise cause of this phenomenon remains an open question, Schulze and Miller propose a rare and powerful process was at play. They are exploring multiple scenarios, including interactions with a potential companion star, a massive pre-supernova eruption or even unusually strong stellar winds.

But, most likely, the team posits this mysterious supernova is the result of a massive star literally tearing itself apart. As the star’s core squeezes inward under its own gravity, it becomes even hotter and denser. The extreme heat and density then reignite nuclear fusion with such incredible intensity that it causes a powerful burst of energy that pushes away the star’s outer layers. Each time the star undergoes a new pair-instability episode, the corresponding pulse sheds more material.

“One of the most recent shell ejections collided with a pre-existing shell, which produced the brilliant emission that we saw as SN2021yfj,” Schulze said.

“While we have a theory for how nature created this particular explosion,” Miller said, “I wouldn’t bet my life that it’s correct, because we still only have one discovered example. This star really underscores the need to uncover more of these rare supernovae to better understand their nature and how they form.”

The study, “Extremely stripped supernova reveals a silicon and sulphur formation site,” was supported by the National Science Foundation. Support from CIERA provided access to ZTF telescope data.

Depiction of the most likely scenario of SN 2021yfj [VIDEO]

Near the end of its life, SN 2021yfj's stripped-to-the-bone progenitor underwent two rare and extremely violent pair-instability episodes, ejecting shells rich in silicon (grey), sulphur (yellow) and argon (purple). The collision of these massive shells is so violent that it created a brilliant supernova that could still be seen at a distance of 2.2 billion light years. SN 2021yfj is so unusual it defines a new class, Type Ien, and the star itself may have survived the event.

Credit

W.M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko

Journal

Nature

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Extremely stripped supernova reveals a silicon and sulfur formation site

Article Publication Date

20-Aug-2025

Feeding massive stars

Streams of gas might lead to the rapid formation of high-mass stars

image:

The dust emission of the high-mass star forming region G336.018-00.827 ALMA1 at radio wavelengths. The star symbol indicates the protostellar position. The gas is rotating and falling along the red and blue arrows. The gas flow (streamer) indicated by the blue arrow transports gas from the molecular cloud core to the high-density region in the vicinity of the protostar.

view moreCredit: KyotoU / Fernando Olguin

Kyoto, Japan -- The size of our universe and the bodies within it is incomprehensible for us lowly humans. The sun has a mass that is more than 330,000 that of our Earth, and yet there are stars in the universe that completely dwarf our sun.

Stars with masses more than eight times that of the sun are considered high mass stars. These form rapidly in a process that gives off stellar wind and radiation, which could not result in stars of such high mass without somehow overcoming this loss of mass, or feedback. Something is feeding these stars, but how exactly they can accumulate so much mass so quickly has remained a mystery.

Observations of enormous disk-like structures that form around a star -- accretion disks -- had been proposed as the chief way of rapidly feeding young stars. However, a team of researchers from several institutions including Kyoto University and the University of Tokyo, has discovered another possibility.

"Our work seems to show that these structures are being fed by streamers, which are flows of gas that bring matter from scales larger than a thousand astronomical units, essentially acting as massive gas highways," says corresponding author Fernando Olguin.

Following on previous research, the team required a higher angular resolution to observe this system in detail, since regions forming high-mass stars are more distant than those with lower mass. The researchers utilized the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, a powerful telescope in Chile composed of an array of antennae that can observe dust and molecular line emissions at millimeter wavelengths.

Their observations revealed a young star feeding from potentially two streamers. One such streamer was connected to the central region of the star, with a velocity gradient indicative of rotation and possibly infall. This suggests that the streamer carries enough matter at a high rate to quench feedback effects from the young star, eventually contributing to the overly dense region observed around the central massive star.

The research team expected to see a dust disk or torus of several hundreds astronomical units in size, but they did not expect the spiral arms to reach far closer to the central source.

"We found streamers feeding what at that time was thought to be a disk, but to our surprise, there is either no disk or it is extremely small," says Olguin.

These results suggest that, independent of the presence of a disk around the central star, streamers can transport large amounts of gas to feed star-forming regions, even in the presence of feedback from the central star.

Next, the team plans to expand their research by studying other regions to see if this is a common mode of accretion that results in the formation of massive stars. They also plan to explore the gas close to the star to determine whether they can confirm, or rule out, the presence of small disks.

###

The paper "Massive extended streamers feed high-mass young stars" appeared on 20 August 2025 in Science Advances, with doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adw4512

About Kyoto University

Kyoto University is one of Japan and Asia's premier research institutions, founded in 1897 and responsible for producing numerous Nobel laureates and winners of other prestigious international prizes. A broad curriculum across the arts and sciences at undergraduate and graduate levels complements several research centers, facilities, and offices around Japan and the world. For more information, please see: http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en

Journal

Science Advances

Method of Research

Imaging analysis

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Massive extended streamers feed high-mass young stars

Article Publication Date

20-Aug-2025

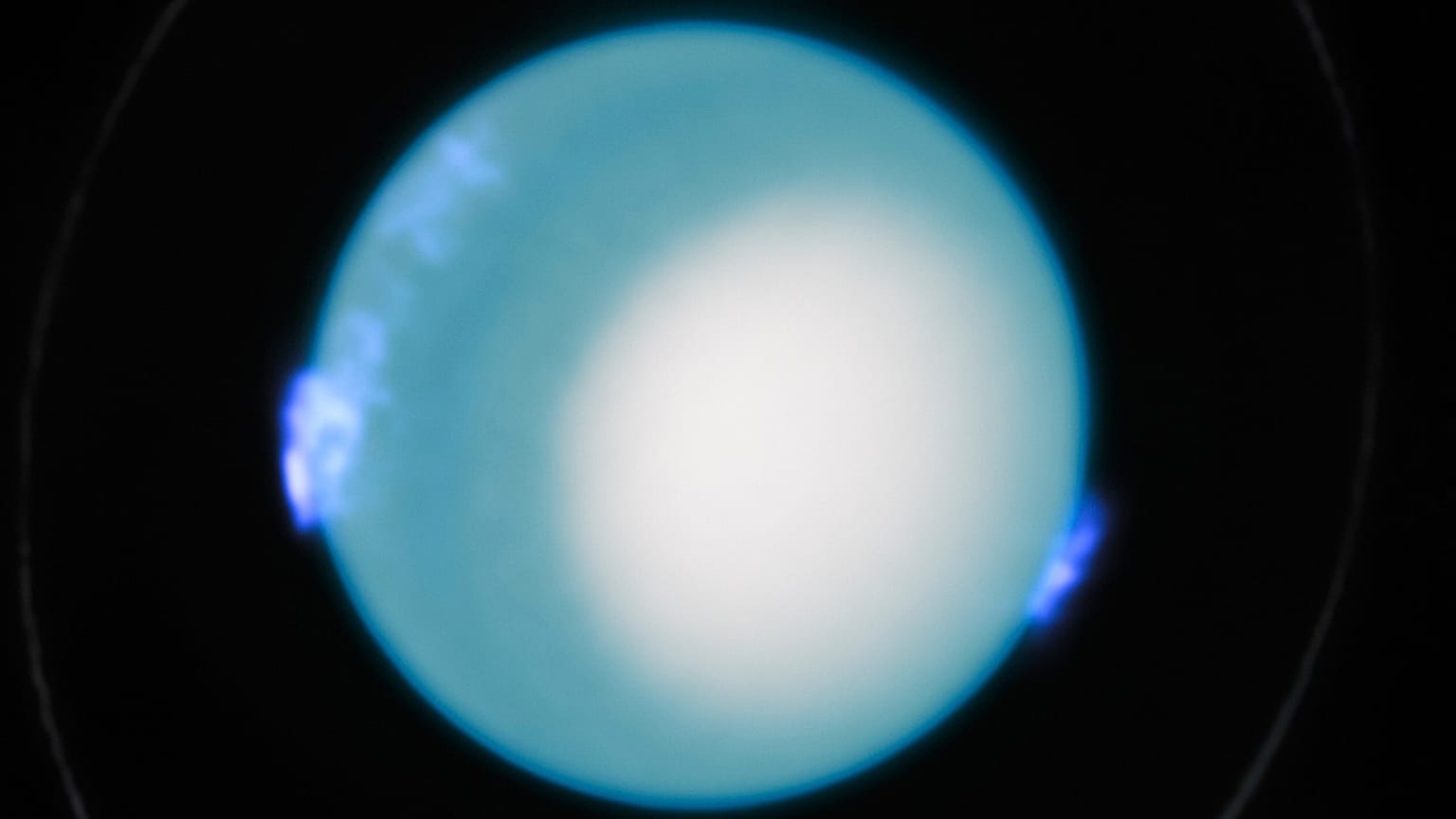

Tiny new moon spotted around Uranus by powerful space telescope

The new moon, still nameless, ups the planet's total moon count to 29.

The Webb Space Telescope has spotted a new tiny moon orbiting Uranus.

The new member of the lunar gang, announced Tuesday by American space agency NASA, appears to be just 10 kilometres wide. It was spotted by the telescope's near-infrared camera during observations in February.

Scientists think it hid for so long – even eluding the Voyager 2 spacecraft during its flyby about 40 years ago – because of its faintness and small size.

Uranus has 28 known moons that are named after characters from Shakespeare and Alexander Pope. About half are smaller and orbit the planet at closer range.

The new moon, still nameless, ups the planet's total count to 29.

The new addition could hint at more bite-sized moons waiting to be found around Uranus, said planetary scientist Matthew Tiscareno with the US-based SETI Institute, who was involved in the discovery.

“There's probably a lot more of them and we just need to keep looking,” said Tiscareno.

Other planets in the solar system have even more moons. Saturn has 274 known moons, while Jupiter has 95, Neptune has 16, Mars has two, the Earth has one, and Mercury and Venus have none, according to NASA.