How Government-Run Health Care Actually Works

BY DAVID H. FREEDMAN ON 03/16/20

"Medicare For All" is probably the best-known plank in Senator Bernie Sanders' campaign platform. He wants the federal government to take over private health care insurance and replace it with a comprehensive, single-payer program. Under this plan, every U.S. resident would automatically be insured for nearly every contingency—hospital stays, dental care, mental health, ambulance services and long-term care, among other things—with nearly no copays or deductibles. Grandma needs a nursing home? That's covered. Your son needs counseling for a drug addiction? Covered. No surprise bills, no copays.

Critics slam the plan as too expensive; Sanders insists it would save money overall. Everyone agrees, however, that Medicare for All would amount to a massive transfer of spending from the private sector to the U.S. government. And there lies the rub. Can the U.S. government be trusted to manage a complex, fast-moving industry in which innovation and efficiency—qualities more often associated with the private sector than a government bureaucracy—are matters of life and death for so many Americans? The question makes many people nervous and puts Sanders' supporters on the defensive.

What goes largely unappreciated in this debate is that the U.S. government already owns and runs one of the most successful health care operations in the world. It's taken on the care of millions of some of America's most challenging patients, including residents of isolated rural communities and older patients who need long-term care. It does so while eliminating many of the racial disparities that haunt American health care. It trains most of America's doctors. It is a leader in telehealth, electronic health care records, precision medicine and many other important, forward-looking technologies. It earns quality-of-care ratings that most hospitals would envy. It keeps costs generally below average and charges most patients little or nothing.

The system is the Veterans Health Administration—commonly referred to as the VA, after the broader agency that runs it, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs—along with the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, operated by the Defense Department. Walter Reed serves about a million active-duty military personnel, military retirees and others. The VA serves about 9 million patients, the vast majority of whom are U.S. military veterans. It provides government health care on an enormous scale, entirely administered, delivered and paid for by the U.S. government. If that's not socialism, what is?

"Medicare For All" is probably the best-known plank in Senator Bernie Sanders' campaign platform. He wants the federal government to take over private health care insurance and replace it with a comprehensive, single-payer program. Under this plan, every U.S. resident would automatically be insured for nearly every contingency—hospital stays, dental care, mental health, ambulance services and long-term care, among other things—with nearly no copays or deductibles. Grandma needs a nursing home? That's covered. Your son needs counseling for a drug addiction? Covered. No surprise bills, no copays.

Critics slam the plan as too expensive; Sanders insists it would save money overall. Everyone agrees, however, that Medicare for All would amount to a massive transfer of spending from the private sector to the U.S. government. And there lies the rub. Can the U.S. government be trusted to manage a complex, fast-moving industry in which innovation and efficiency—qualities more often associated with the private sector than a government bureaucracy—are matters of life and death for so many Americans? The question makes many people nervous and puts Sanders' supporters on the defensive.

What goes largely unappreciated in this debate is that the U.S. government already owns and runs one of the most successful health care operations in the world. It's taken on the care of millions of some of America's most challenging patients, including residents of isolated rural communities and older patients who need long-term care. It does so while eliminating many of the racial disparities that haunt American health care. It trains most of America's doctors. It is a leader in telehealth, electronic health care records, precision medicine and many other important, forward-looking technologies. It earns quality-of-care ratings that most hospitals would envy. It keeps costs generally below average and charges most patients little or nothing.

The system is the Veterans Health Administration—commonly referred to as the VA, after the broader agency that runs it, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs—along with the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, operated by the Defense Department. Walter Reed serves about a million active-duty military personnel, military retirees and others. The VA serves about 9 million patients, the vast majority of whom are U.S. military veterans. It provides government health care on an enormous scale, entirely administered, delivered and paid for by the U.S. government. If that's not socialism, what is?

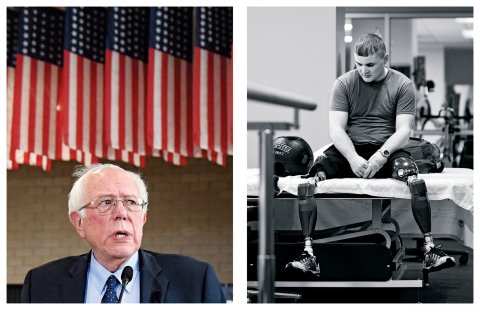

Senator Bernie Sanders (i-Vermont) speaks during a health care rally

at the 2017 Convention of the California Nurses Association/National

Nurses Organizing Committee on September 22, 2017 in San Francisco,

CaliforniaJUSTIN SULLIVAN/GETTY

The VA is, in fact, more of a socialist enterprise than anything Bernie Sanders has proposed. His Medicare for All would be an insurance program—patients would use private doctors, hospitals and clinics, who would then be reimbursed by Uncle Sam. (Much like Medicare, except Sanders' plan would pay the costs of health care received by nearly all Americans.) The VA, by contrast, directly employs 11,000 doctors and owns its 1,200 hospitals.

The VA has become something of a darling among the progressive wing of the Democratic party. Sanders' plan would not only preserve the VA intact, it would increase funding to fill vacancies left open by the Trump administration. Veterans "know they can get high-quality care at the VA," says his campaign website. "It's our job to make it easier—not harder—for them to get that high-quality care."

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the progressive representative from New York, has also vehemently defended the VA against calls for privatization. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," she admonished critics in a town hall in April 2019. "Who are they trying to fix it for is the question we've got to ask. They're trying to fix the VA for pharmaceutical companies, they're trying to fix the VA for insurance corporations, and ultimately, they're trying to fix the VA for a for-profit health care industry that does not put people or veterans first."

Opponents of national health care point to recent scandals that paint the VA as a troubled bureaucracy that fails to serve its constituents adequately. In recent years, there have been stories of fatally long waits for surgeries, filthy facilities, sexual assault and suspicious deaths. That creates an image of the VA as a cold, clueless, lumbering, third-rate bureaucracy—the kind that awaits Americans if plans to increase the government's role in health care are enacted. "Every one of these plans involves rationing care, restricting access, denying coverage, slashing quality and massively raising taxes," said President Donald Trump in October.

To be sure, the VA is neither perfect nor immune from the challenges of providing health care at a time of rising costs and aging populations. But by focusing on the problems, critics ignore the contrary evidence: by most measures, the VA and its DOD counterpart, Walter Reed, make up arguably the best-run health care operation in the United States.

Comparison Tests

Scrutiny can have an upside. As a public institution, the VA has been subject to many in-depth, independent studies that show how well it stacks up against both private and public health care systems in the U.S.

Quality of care, these studies show, is high in VA hospitals and clinics. In 2018, researchers at Dartmouth College's Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice concluded that VA hospitals "outperform private hospitals in most health care markets throughout the country" when it comes to quality of care. The study's lead author, Dartmouth Institute Professor and physician William Weeks, added at the time that "the VA generally provides truly excellent care."

The Rand Corporation, a respected think tank, came to the same conclusion in 2018. And in a second study, Rand analyzed previous studies of the VA and determined that the VA compares favorably with the private sector. "When you see consistent findings like these, it gives us confidence that they're real," says Rebecca Anhang Price, the senior policy researcher at Rand who led the studies.

Perhaps that's why Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell chose a government hospital—the Bethesda National Naval Medical Center, now known as Walter Reed—in which to have a triple-bypass operation in 2003. That hasn't stopped McConnell from referring to government-sponsored care as a "far-left social experiment" and vowing that legislation to enlarge government's role in health care would never pass while he was speaker.

Comparing VA health care directly against Medicare-Medicaid and private insurance is difficult because the systems are so different. Where comparisons can be made, the results usually suggest that the VA is as good or better than private care, private health insurance and Medicare-Medicaid. A 2015 Gallup poll found that 78 percent of those receiving VA care were satisfied with how the health care system worked, compared to 75 percent of those insured by Medicare, and 69 percent of those insured through their employers. Dartmouth's 2018 study concluded that VA hospitals on average performed better than other hospitals in their regions in key measures of care quality. VA hospital patients had lower rates of readmissions within 30 days and suffered fewer complications from infections, falls and blood clots when they were in the hospital, the study found.

The VA is, in fact, more of a socialist enterprise than anything Bernie Sanders has proposed. His Medicare for All would be an insurance program—patients would use private doctors, hospitals and clinics, who would then be reimbursed by Uncle Sam. (Much like Medicare, except Sanders' plan would pay the costs of health care received by nearly all Americans.) The VA, by contrast, directly employs 11,000 doctors and owns its 1,200 hospitals.

The VA has become something of a darling among the progressive wing of the Democratic party. Sanders' plan would not only preserve the VA intact, it would increase funding to fill vacancies left open by the Trump administration. Veterans "know they can get high-quality care at the VA," says his campaign website. "It's our job to make it easier—not harder—for them to get that high-quality care."

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the progressive representative from New York, has also vehemently defended the VA against calls for privatization. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," she admonished critics in a town hall in April 2019. "Who are they trying to fix it for is the question we've got to ask. They're trying to fix the VA for pharmaceutical companies, they're trying to fix the VA for insurance corporations, and ultimately, they're trying to fix the VA for a for-profit health care industry that does not put people or veterans first."

Opponents of national health care point to recent scandals that paint the VA as a troubled bureaucracy that fails to serve its constituents adequately. In recent years, there have been stories of fatally long waits for surgeries, filthy facilities, sexual assault and suspicious deaths. That creates an image of the VA as a cold, clueless, lumbering, third-rate bureaucracy—the kind that awaits Americans if plans to increase the government's role in health care are enacted. "Every one of these plans involves rationing care, restricting access, denying coverage, slashing quality and massively raising taxes," said President Donald Trump in October.

To be sure, the VA is neither perfect nor immune from the challenges of providing health care at a time of rising costs and aging populations. But by focusing on the problems, critics ignore the contrary evidence: by most measures, the VA and its DOD counterpart, Walter Reed, make up arguably the best-run health care operation in the United States.

Comparison Tests

Scrutiny can have an upside. As a public institution, the VA has been subject to many in-depth, independent studies that show how well it stacks up against both private and public health care systems in the U.S.

Quality of care, these studies show, is high in VA hospitals and clinics. In 2018, researchers at Dartmouth College's Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice concluded that VA hospitals "outperform private hospitals in most health care markets throughout the country" when it comes to quality of care. The study's lead author, Dartmouth Institute Professor and physician William Weeks, added at the time that "the VA generally provides truly excellent care."

The Rand Corporation, a respected think tank, came to the same conclusion in 2018. And in a second study, Rand analyzed previous studies of the VA and determined that the VA compares favorably with the private sector. "When you see consistent findings like these, it gives us confidence that they're real," says Rebecca Anhang Price, the senior policy researcher at Rand who led the studies.

Perhaps that's why Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell chose a government hospital—the Bethesda National Naval Medical Center, now known as Walter Reed—in which to have a triple-bypass operation in 2003. That hasn't stopped McConnell from referring to government-sponsored care as a "far-left social experiment" and vowing that legislation to enlarge government's role in health care would never pass while he was speaker.

Comparing VA health care directly against Medicare-Medicaid and private insurance is difficult because the systems are so different. Where comparisons can be made, the results usually suggest that the VA is as good or better than private care, private health insurance and Medicare-Medicaid. A 2015 Gallup poll found that 78 percent of those receiving VA care were satisfied with how the health care system worked, compared to 75 percent of those insured by Medicare, and 69 percent of those insured through their employers. Dartmouth's 2018 study concluded that VA hospitals on average performed better than other hospitals in their regions in key measures of care quality. VA hospital patients had lower rates of readmissions within 30 days and suffered fewer complications from infections, falls and blood clots when they were in the hospital, the study found.

IN THE MAGAZINE

PERISCOPECULTURE

Sanders Is Beating Biden In the Race for Donations From Hollywood's Elite

America already has government-run health care. Here's how it works.

FROM LEFT: ETHAN MILLER/GETTY; DANIEL C. BRITT/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY

Perhaps most important, vets themselves tend to speak highly of the system. A 2019 Veterans of Foreign Wars survey of thousands of vets found that 91 percent of respondents recommend VA care to other vets, and most chose the VA for their own health care even though 98 percent of them had other options. One of them is Christine Griffin, a Boston-area army veteran and a lawyer who is partially paralyzed, has top-notch private health care insurance. She also lives within shouting distance of some of America's most revered private hospitals. For her own care, however, she chooses the local VA, including the tests and treatments she needed after she was diagnosed with breast cancer. "Everything is accessible here, and the women's imaging center is almost like a spa," she says. "They're just so good at so many things."

A common criticism of government-run health care is that wait times can be oppressive. In Australia, for example, wait times are twice as high in public hospitals as in private facilities. In 2016 the GAO found that wait times for a third of the VA's primary-care visits were longer than a month, and last year the agency said some vets who were referred to health care providers outside the VA had to wait as long 70 days for treatment. By most accounts, wait times have improved since then. Studies have shown that the VA's wait times for care turn out to be shorter on average than those in the private sector for all types of treatments, with the one exception of elective orthopedic procedures such as knee surgery, where delays usually pose little risk to the patient. According to that 2019 VFW survey, 84 percent of vets said they were able to get care "in a timely manner."

"Government health care" conjures images of a cumbersome bureaucracy. Compared to the Byzantine rules and requirements of the private health care insurance industry, however, the VA has less bureaucratic overhead, says Neil Evans, a physician who runs the VA's Office of Connected Care. VA doctors don't have to get pre-authorization from insurance companies or anyone else. "I struggle to think of a single time when I felt an intervention was in the best interests of a patient and I couldn't get that done— even if it was expensive," he says. The need for patients in the private health care system to get insurance-company approval can wreak havoc on care.

The result, as too many in the U.S. know all too well, is private-sector care that tends to be fragmented and frequently inadequate. And it's almost always costly, which often translates to no care at all. Studies show that a third of Americans report they avoided getting care within the past year because of costs, more than any other industrialized nation.

Perhaps most important, vets themselves tend to speak highly of the system. A 2019 Veterans of Foreign Wars survey of thousands of vets found that 91 percent of respondents recommend VA care to other vets, and most chose the VA for their own health care even though 98 percent of them had other options. One of them is Christine Griffin, a Boston-area army veteran and a lawyer who is partially paralyzed, has top-notch private health care insurance. She also lives within shouting distance of some of America's most revered private hospitals. For her own care, however, she chooses the local VA, including the tests and treatments she needed after she was diagnosed with breast cancer. "Everything is accessible here, and the women's imaging center is almost like a spa," she says. "They're just so good at so many things."

A common criticism of government-run health care is that wait times can be oppressive. In Australia, for example, wait times are twice as high in public hospitals as in private facilities. In 2016 the GAO found that wait times for a third of the VA's primary-care visits were longer than a month, and last year the agency said some vets who were referred to health care providers outside the VA had to wait as long 70 days for treatment. By most accounts, wait times have improved since then. Studies have shown that the VA's wait times for care turn out to be shorter on average than those in the private sector for all types of treatments, with the one exception of elective orthopedic procedures such as knee surgery, where delays usually pose little risk to the patient. According to that 2019 VFW survey, 84 percent of vets said they were able to get care "in a timely manner."

"Government health care" conjures images of a cumbersome bureaucracy. Compared to the Byzantine rules and requirements of the private health care insurance industry, however, the VA has less bureaucratic overhead, says Neil Evans, a physician who runs the VA's Office of Connected Care. VA doctors don't have to get pre-authorization from insurance companies or anyone else. "I struggle to think of a single time when I felt an intervention was in the best interests of a patient and I couldn't get that done— even if it was expensive," he says. The need for patients in the private health care system to get insurance-company approval can wreak havoc on care.

The result, as too many in the U.S. know all too well, is private-sector care that tends to be fragmented and frequently inadequate. And it's almost always costly, which often translates to no care at all. Studies show that a third of Americans report they avoided getting care within the past year because of costs, more than any other industrialized nation.

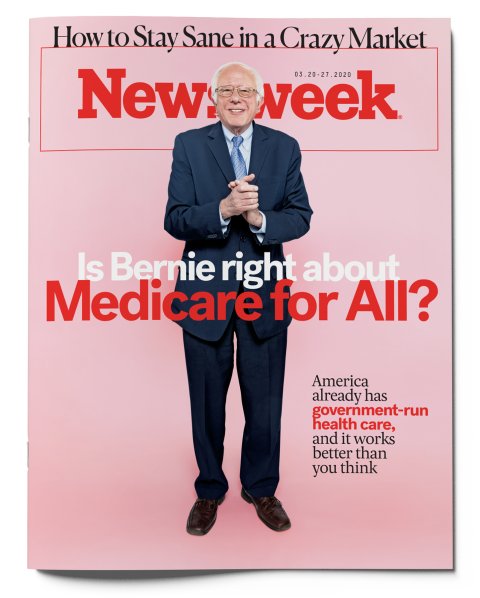

A sign marks the entrance to the Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital on

May 30, 2014 in Hines, Illinois. Hines. A doctor at a VA Florida

hospital has been shot by a double amputee in a wheelchair.

SCOTT OLSON/GETTY IMAGES

An Edge in Innovation

The VA has managed to be at the forefront of virtually every medical trend that experts say is crucial to improving care and reducing costs. For one, it offers an alternative to "fee-for-service" reimbursement, in which hospitals are paid more for providing more treatments, a perverse incentive that contributes to high costs and lack of preventative care. The VA, by contrast, practices value-based care, under which health care providers are financially incentivized to keep patients healthier. The private-health care industry, which has thrived on fee-for-service, is in no hurry to make the switch even while health care costs have soared to more than $11,500 per person, a 30 percent rise in inflation-adjusted dollars since 2003.

Under value-based care, the healthier patients stay, the less the VA has to dig into its budget to provide more treatment. Does this save on costs? It's nearly impossible to compare costs in such health care systems. The VA, for instance, doesn't even bill patients for the care it provides. Its patients tend to have more health challenges than other patients, which include ordinary back injuries as well as exposure to Agent Orange and traumatic brain injury from combat. And they tend to stay with the VA longer because it provides nursing-home and end-of-life care. Studies have shown that many of the VA's patients would be turned away by most private health care insurance companies. "About a third of Americans have chronic, non-cancer pain," says Carolyn Clancy, a physician and the deputy under secretary for discovery, education and affiliate networks at the VA. "For vets it's about 60 percent."

Still, studies suggest that where comparisons can be made, care in the VA costs about 10 percent less than Medicare, even though Medicare pays about half as much as private insurance does for similar treatments, according to another Rand study. That's because the VA is constantly hunting for ways to eliminate inefficiencies, including tests and treatments that don't offer much benefit for patients, says Ryan Vega, a physician who heads the VA's health care innovation efforts. "If we can do something for a vet that will make their lives better, we'll do it, even if it costs more," insists Vega. "But if it doesn't provide better care, we look to reduce it."

Vega says the VA regularly "de-prescribes" medicines that haven't ended up producing the hoped-for benefits, eliminates tests that aren't leading to better outcomes and constantly hunts down cheaper ways to get good results. For example, the VA has pioneered a drive to increase the rate of toothbrushing among patients at its hospitals, after discovering it reduced by 90 percent the number of cases of nonventilator, hospital-acquired pneumonia, an illness that costs the U.S. $35 billion a year. "It's reasonable to expect that an institution that isn't being paid more to do more will avoid unnecessary costs," says Rand's Anhang Price. "You might worry that they have an incentive to undertreat patients, but we can't find evidence of that in the VA."

An Edge in Innovation

The VA has managed to be at the forefront of virtually every medical trend that experts say is crucial to improving care and reducing costs. For one, it offers an alternative to "fee-for-service" reimbursement, in which hospitals are paid more for providing more treatments, a perverse incentive that contributes to high costs and lack of preventative care. The VA, by contrast, practices value-based care, under which health care providers are financially incentivized to keep patients healthier. The private-health care industry, which has thrived on fee-for-service, is in no hurry to make the switch even while health care costs have soared to more than $11,500 per person, a 30 percent rise in inflation-adjusted dollars since 2003.

Under value-based care, the healthier patients stay, the less the VA has to dig into its budget to provide more treatment. Does this save on costs? It's nearly impossible to compare costs in such health care systems. The VA, for instance, doesn't even bill patients for the care it provides. Its patients tend to have more health challenges than other patients, which include ordinary back injuries as well as exposure to Agent Orange and traumatic brain injury from combat. And they tend to stay with the VA longer because it provides nursing-home and end-of-life care. Studies have shown that many of the VA's patients would be turned away by most private health care insurance companies. "About a third of Americans have chronic, non-cancer pain," says Carolyn Clancy, a physician and the deputy under secretary for discovery, education and affiliate networks at the VA. "For vets it's about 60 percent."

Still, studies suggest that where comparisons can be made, care in the VA costs about 10 percent less than Medicare, even though Medicare pays about half as much as private insurance does for similar treatments, according to another Rand study. That's because the VA is constantly hunting for ways to eliminate inefficiencies, including tests and treatments that don't offer much benefit for patients, says Ryan Vega, a physician who heads the VA's health care innovation efforts. "If we can do something for a vet that will make their lives better, we'll do it, even if it costs more," insists Vega. "But if it doesn't provide better care, we look to reduce it."

Vega says the VA regularly "de-prescribes" medicines that haven't ended up producing the hoped-for benefits, eliminates tests that aren't leading to better outcomes and constantly hunts down cheaper ways to get good results. For example, the VA has pioneered a drive to increase the rate of toothbrushing among patients at its hospitals, after discovering it reduced by 90 percent the number of cases of nonventilator, hospital-acquired pneumonia, an illness that costs the U.S. $35 billion a year. "It's reasonable to expect that an institution that isn't being paid more to do more will avoid unnecessary costs," says Rand's Anhang Price. "You might worry that they have an incentive to undertreat patients, but we can't find evidence of that in the VA."

Is Bernie Sanders right about Medicare for All?

PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRISTOPHER LANE

Another critical area where the VA has leapt far out in front of most of the rest of health care is in addressing the "social determinants of health"—that is, life challenges such as inadequate housing, poverty and joblessness, as well as lifestyle and mental health issues such as poor diet, loneliness, stress and depression, that can have a big impact on health and well-being. Social determinants have about four times the impact on a patient's health as the medical care they receive. Other industrialized nations spend twice as much on such social problems as they do on health care; the U.S. spends half as much, and the U.S. health care system by and large ignores them.

Through the VA, vets have access to professionals who can help them cope with their life challenges, including social workers, counselors, behavioral coaches, acupuncturists and tai chi instructors. In many cases, after meeting with a patient, a VA doctor will simply walk the patient down the hall to meet a counselor or a coach. "We want to offer a big repertoire of tools for dealing with stress, chronic pain and other whole-health problems," says Ben Kliger, a physician who runs the VA's "integrative health" and "cultural transformation" initiatives. "Once a vet gets involved in these other services, their overall costs tend to go down."

"We've changed the conversation here so it's not just about disease," he says.

High-Tech Medicine

The VA frequently jumps ahead of the rest of health care in adopting new technology. Back in 2010, Eric Dusseux, CEO of medical-tech company Bionik, went looking for hospitals willing to experimentally deploy the company's groundbreaking robots, designed to exercise the arms of stroke victims. He soon found a willing partner in the VA. Ultimately, it deployed the robots in 12 of its hospitals, leading to the largest study ever of robotic patient rehabilitation—a study so successful that robots are now part of standard stroke-care guidelines due to the improved outcomes and lowered overall costs from the technology. "They were very receptive and forward-thinking," says Dusseux of the hospital system.

The VA is also pioneering the use of 3D printers to create highly accurate models of the internal organs of individual patients who are scheduled for complex surgeries, so that surgeons can better prepare for the operations by examining the models. In one of the most ambitious health-data projects in the world, it is analyzing the complete service histories and medical records, along with DNA samples, of nearly 800,000 veterans in order to find links between their genes; environments; habits such as diet, medications and diseases, with an eye to spotting new strategies for improving long-term health. And it has launched an institute entirely dedicated to applying artificial intelligence approaches to health care.

The VA has also established a system for automatically analyzing electronic health care records throughout the system in order to spot improvements in patient outcomes at any of its facilities, to see if there are any innovations underlying an improvement that can be quickly shared throughout all VA facilities. "We send teams to learn from those sites that are doing well with outcomes, and then deploy them to any sites that might be having trouble," says Joe Francis, a physician and chief improvement and analytics officer at the VA. "You can't do that sort of thing in the private sector, because there are too many competitive and time pressures." To dig out even more innovation, the VA sponsors a Shark-Tank-style competition for all its employees, the most recent of which inspired some 500 promising ideas aimed at improving care or lowering costs.

The VA's telehealth capabilities, too, are years ahead of most other health care organizations. Some 100,000 vets have logged more than a million videoconference visits with VA clinicians, all of which were entirely free. That's a critical service for the 30 percent of VA patients who live in rural areas. And many of those who can't or don't want to conduct the video visit from their homes, perhaps because of privacy concerns during an exam, will soon be able to do so from one of a network of telehealth exam "pods" the VA is setting up at Walmarts and at American Legion and VFW sites. The first such pod has already opened up in Eureka, Montana, serving some 300 vets.

Tele-visits return large benefits both in reduced costs and patient outcomes for chronic illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease, which afflict 60 percent of adult Americans. They require frequent monitoring and check-ins to avoid the sorts of sudden health crises that can send a patient to the emergency room and an in-patient stay, easily costing a health care system tens of thousands of dollars. "Patients who try it, like it," says Leonie Heyworth, the physician who heads the VA's telehealth efforts. "If they have to fight traffic to get here they can be a mess by the time they come into my office." That's why the VA's video patients have 28 percent fewer missed appointments than in-person patients.

The VA's telehealth practices go beyond convenience. Videoconferencing gives both patients and their doctors fast access to advanced specialty consults available in a handful of leading hospitals. "We use virtual care to match patients to the best specialist for their needs across the entire system, wherever they are," says the VA's Evans. "Just because you're at one of our smaller hospitals or clinics doesn't mean you can't benefit from the resources you'd have if you were at a top-notch medical center."

That tele-specialty capability is one way that the VA is moving to the forefront of so-called precision medicine, an effort to develop treatments that are custom-tailored to a patient's genes and other characteristics. Precision medicine is especially promising in cancer, where doctors use it to tell ahead of time whether a patient will respond to a specific treatment.

In the U.S., only a tenth of cancer patients get precision-medicine testing. At the VA, half of lung cancer patients now get it, as do a quarter of those with prostate cancer—the two most common types of cancer among vets. Unlike most rural patients, who don't have access to precision medicine, vets who live in rural areas are getting tested at the same rates as those near cities. The VA "telegenomics" hub in Salt Lake City services the entire VA system; any physician in the VA can access it on behalf of a patient. "Now we're working to provide rural vets with access to experimental cancer drugs, too," says Michael Kelley, a physician who directs the VA's national oncology program. He notes the VA has also been looking at bringing artificial intelligence software to bear on analyzing vets' tumors.

Answering the Critics

To be sure, the VA has had its share of well-publicized problems. In January, the VA demanded a co-pay on replacement prosthetic limbs from a vet when the prostheses were stolen from his room at a VA long-term-care home. VA officials allegedly tried to discredit a legislative aide who reported being groped by another patient at a VA facility. A Federal grand jury is currently looking into whether a former nursing assistant at a VA hospital in West Virginia may have killed 11 patients with insulin overdoses.

In one of the more sensational scandals, in 2014 some VA employees were reportedly falsifying records of how long patients had to wait for appointments and as many as 40 vets died while waiting. Further investigation suggested that the problem wasn't unusually long wait times, but rather that the VA had been given a target by government officials of limiting wait times to under 14 days—a system-wide goal that few private health care systems could meet. A report later that year from the VA inspector general found that six of the deaths might have been related to wait times, and that the other deaths were consistent with the condition of the patients in question, most of whom had complex health challenges.

The VA doesn't offer excuses for the falsifications. The VA's Clancy points out that as a large government agency the VA has to accept a greater level of scrutiny than its counterparts in the private sector. Its flaws are more readily decried in the national press and it is more directly answerable to the public. In the end, she argues, that closer, less-forgiving, more visible oversight ultimately leads to more accountability and improvement. The VA's overall record seems to bear that claim out.

The VA's foibles also become political weapons in the ongoing debate over the virtues of private versus government-run health care. One of the biggest VA-health-care-related complaints coming out of Washington recently doesn't concern the VA's poor performance but rather the push toward privatization. Veterans' advocates complain that the Trump administration seems to be pushing more vets toward private health care, in part by not filling some VA health care positions that are currently open. "The administration is setting us up to fail so they can dismantle veterans' preferred health care provider," Alma Lee, National Veterans Affairs council president for the American Federation of Government Employees, told the Military Times.

If the VA does in fact provide a better health care system than what most Americans have access to, then vets have surely earned that privilege. Nobody is proposing a similar health care system for all Americans. But Sanders' Medicare for All plan would establish universal coverage, and it would almost certainly be a tougher negotiator of prices than private insurers are. It would likely force private hospitals to focus on care that delivers the best health results at the lowest cost, as the VA does today.

In those respects, Medicare for All could remake the U.S. health care system in the VA's image. To hear most vets tell it, that would be an improvement.

Another critical area where the VA has leapt far out in front of most of the rest of health care is in addressing the "social determinants of health"—that is, life challenges such as inadequate housing, poverty and joblessness, as well as lifestyle and mental health issues such as poor diet, loneliness, stress and depression, that can have a big impact on health and well-being. Social determinants have about four times the impact on a patient's health as the medical care they receive. Other industrialized nations spend twice as much on such social problems as they do on health care; the U.S. spends half as much, and the U.S. health care system by and large ignores them.

Through the VA, vets have access to professionals who can help them cope with their life challenges, including social workers, counselors, behavioral coaches, acupuncturists and tai chi instructors. In many cases, after meeting with a patient, a VA doctor will simply walk the patient down the hall to meet a counselor or a coach. "We want to offer a big repertoire of tools for dealing with stress, chronic pain and other whole-health problems," says Ben Kliger, a physician who runs the VA's "integrative health" and "cultural transformation" initiatives. "Once a vet gets involved in these other services, their overall costs tend to go down."

"We've changed the conversation here so it's not just about disease," he says.

High-Tech Medicine

The VA frequently jumps ahead of the rest of health care in adopting new technology. Back in 2010, Eric Dusseux, CEO of medical-tech company Bionik, went looking for hospitals willing to experimentally deploy the company's groundbreaking robots, designed to exercise the arms of stroke victims. He soon found a willing partner in the VA. Ultimately, it deployed the robots in 12 of its hospitals, leading to the largest study ever of robotic patient rehabilitation—a study so successful that robots are now part of standard stroke-care guidelines due to the improved outcomes and lowered overall costs from the technology. "They were very receptive and forward-thinking," says Dusseux of the hospital system.

The VA is also pioneering the use of 3D printers to create highly accurate models of the internal organs of individual patients who are scheduled for complex surgeries, so that surgeons can better prepare for the operations by examining the models. In one of the most ambitious health-data projects in the world, it is analyzing the complete service histories and medical records, along with DNA samples, of nearly 800,000 veterans in order to find links between their genes; environments; habits such as diet, medications and diseases, with an eye to spotting new strategies for improving long-term health. And it has launched an institute entirely dedicated to applying artificial intelligence approaches to health care.

The VA has also established a system for automatically analyzing electronic health care records throughout the system in order to spot improvements in patient outcomes at any of its facilities, to see if there are any innovations underlying an improvement that can be quickly shared throughout all VA facilities. "We send teams to learn from those sites that are doing well with outcomes, and then deploy them to any sites that might be having trouble," says Joe Francis, a physician and chief improvement and analytics officer at the VA. "You can't do that sort of thing in the private sector, because there are too many competitive and time pressures." To dig out even more innovation, the VA sponsors a Shark-Tank-style competition for all its employees, the most recent of which inspired some 500 promising ideas aimed at improving care or lowering costs.

The VA's telehealth capabilities, too, are years ahead of most other health care organizations. Some 100,000 vets have logged more than a million videoconference visits with VA clinicians, all of which were entirely free. That's a critical service for the 30 percent of VA patients who live in rural areas. And many of those who can't or don't want to conduct the video visit from their homes, perhaps because of privacy concerns during an exam, will soon be able to do so from one of a network of telehealth exam "pods" the VA is setting up at Walmarts and at American Legion and VFW sites. The first such pod has already opened up in Eureka, Montana, serving some 300 vets.

Tele-visits return large benefits both in reduced costs and patient outcomes for chronic illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease, which afflict 60 percent of adult Americans. They require frequent monitoring and check-ins to avoid the sorts of sudden health crises that can send a patient to the emergency room and an in-patient stay, easily costing a health care system tens of thousands of dollars. "Patients who try it, like it," says Leonie Heyworth, the physician who heads the VA's telehealth efforts. "If they have to fight traffic to get here they can be a mess by the time they come into my office." That's why the VA's video patients have 28 percent fewer missed appointments than in-person patients.

The VA's telehealth practices go beyond convenience. Videoconferencing gives both patients and their doctors fast access to advanced specialty consults available in a handful of leading hospitals. "We use virtual care to match patients to the best specialist for their needs across the entire system, wherever they are," says the VA's Evans. "Just because you're at one of our smaller hospitals or clinics doesn't mean you can't benefit from the resources you'd have if you were at a top-notch medical center."

That tele-specialty capability is one way that the VA is moving to the forefront of so-called precision medicine, an effort to develop treatments that are custom-tailored to a patient's genes and other characteristics. Precision medicine is especially promising in cancer, where doctors use it to tell ahead of time whether a patient will respond to a specific treatment.

In the U.S., only a tenth of cancer patients get precision-medicine testing. At the VA, half of lung cancer patients now get it, as do a quarter of those with prostate cancer—the two most common types of cancer among vets. Unlike most rural patients, who don't have access to precision medicine, vets who live in rural areas are getting tested at the same rates as those near cities. The VA "telegenomics" hub in Salt Lake City services the entire VA system; any physician in the VA can access it on behalf of a patient. "Now we're working to provide rural vets with access to experimental cancer drugs, too," says Michael Kelley, a physician who directs the VA's national oncology program. He notes the VA has also been looking at bringing artificial intelligence software to bear on analyzing vets' tumors.

Answering the Critics

To be sure, the VA has had its share of well-publicized problems. In January, the VA demanded a co-pay on replacement prosthetic limbs from a vet when the prostheses were stolen from his room at a VA long-term-care home. VA officials allegedly tried to discredit a legislative aide who reported being groped by another patient at a VA facility. A Federal grand jury is currently looking into whether a former nursing assistant at a VA hospital in West Virginia may have killed 11 patients with insulin overdoses.

In one of the more sensational scandals, in 2014 some VA employees were reportedly falsifying records of how long patients had to wait for appointments and as many as 40 vets died while waiting. Further investigation suggested that the problem wasn't unusually long wait times, but rather that the VA had been given a target by government officials of limiting wait times to under 14 days—a system-wide goal that few private health care systems could meet. A report later that year from the VA inspector general found that six of the deaths might have been related to wait times, and that the other deaths were consistent with the condition of the patients in question, most of whom had complex health challenges.

The VA doesn't offer excuses for the falsifications. The VA's Clancy points out that as a large government agency the VA has to accept a greater level of scrutiny than its counterparts in the private sector. Its flaws are more readily decried in the national press and it is more directly answerable to the public. In the end, she argues, that closer, less-forgiving, more visible oversight ultimately leads to more accountability and improvement. The VA's overall record seems to bear that claim out.

The VA's foibles also become political weapons in the ongoing debate over the virtues of private versus government-run health care. One of the biggest VA-health-care-related complaints coming out of Washington recently doesn't concern the VA's poor performance but rather the push toward privatization. Veterans' advocates complain that the Trump administration seems to be pushing more vets toward private health care, in part by not filling some VA health care positions that are currently open. "The administration is setting us up to fail so they can dismantle veterans' preferred health care provider," Alma Lee, National Veterans Affairs council president for the American Federation of Government Employees, told the Military Times.

If the VA does in fact provide a better health care system than what most Americans have access to, then vets have surely earned that privilege. Nobody is proposing a similar health care system for all Americans. But Sanders' Medicare for All plan would establish universal coverage, and it would almost certainly be a tougher negotiator of prices than private insurers are. It would likely force private hospitals to focus on care that delivers the best health results at the lowest cost, as the VA does today.

In those respects, Medicare for All could remake the U.S. health care system in the VA's image. To hear most vets tell it, that would be an improvement.

No comments:

Post a Comment