As record fire years continue, USFS “forestry technicians” push for better working conditions.

Among those problems is their classification as forestry technicians, instead of being fully recognized for their firefighting work.

“What the federal government is doing is asking 20-year-olds to risk their lives for $13 to $15 and say, ‘Sayonara,’ with no retirement benefits, nothing,”

United States Forest Service “forestry technicians” are pushing for fairer wages and better working conditions. Cornelia Li / for NBC News

Oct. 31, 2020,

By Cyrus Farivar and Alicia Victoria Lozano

What started as a single tree fire in the mountains of Idaho in 2012 quickly escalated into a smoke-filled inferno that surrounded United States Forest Service helicopter rappeller Jonathon Golden and his small team.

Capable of accessing land that is too rugged or steep to reach by foot, rappel crews are the first to respond to wildfires buried deep within forests. Their goal is simple: stop small fires before they balloon out of control.

Golden, who retired from the agency in 2019, was the first of his four-person team to rappel into the smoldering ridge. He remembers the smoke being so thick that not even the whirl of the helicopter improved visibility on the ground.

“One tree turned into five, five trees turned into 20. It was this cascade of fire erupting,” Golden said. “You could hear the unmistakable sound of a freight train of fire roaring up at you.”

Oct. 31, 2020,

By Cyrus Farivar and Alicia Victoria Lozano

What started as a single tree fire in the mountains of Idaho in 2012 quickly escalated into a smoke-filled inferno that surrounded United States Forest Service helicopter rappeller Jonathon Golden and his small team.

Capable of accessing land that is too rugged or steep to reach by foot, rappel crews are the first to respond to wildfires buried deep within forests. Their goal is simple: stop small fires before they balloon out of control.

Golden, who retired from the agency in 2019, was the first of his four-person team to rappel into the smoldering ridge. He remembers the smoke being so thick that not even the whirl of the helicopter improved visibility on the ground.

“One tree turned into five, five trees turned into 20. It was this cascade of fire erupting,” Golden said. “You could hear the unmistakable sound of a freight train of fire roaring up at you.”

A forest service helicopter returns to the south fork of the Payette River on Aug. 6, 2012, after dropping water on the Springs Fire, east of Banks, Idaho.

Joe Jaszewski / The Idaho Statesman via AP

Golden, who was 30 years old at the time, had heard about previous firefighter fatalities in the region and didn’t want to take any chances. He was working to establish an escape route when one of his crew members went “rogue,” compromising the team’s ability to stay together.

Using his radio, Golden asked for additional air support but other crews were tied up with their own attack plans. His team was forced to find its own way out.

“I thought we were done, frankly,” Golden said. “I thought we were going to die.”

Eight years later, Golden still cannot shake the experience. He was forced to leave behind his equipment and pack, including his wallet and many of his belongings. They were all destroyed in what was later named the Mustang Fire, which incinerated more than 300,000 acres in the Salmon-Challis National Forest.

Golden was a temporary seasonal forestry technician at the time and never received treatment for what he thinks could be post-traumatic stress. He took just one day off to order a new bank card and was back at work the next day. When he tried to talk to his supervisor about the experience, he was told to move on: “You might as well forget about it.”

Golden, who was 30 years old at the time, had heard about previous firefighter fatalities in the region and didn’t want to take any chances. He was working to establish an escape route when one of his crew members went “rogue,” compromising the team’s ability to stay together.

Using his radio, Golden asked for additional air support but other crews were tied up with their own attack plans. His team was forced to find its own way out.

“I thought we were done, frankly,” Golden said. “I thought we were going to die.”

Eight years later, Golden still cannot shake the experience. He was forced to leave behind his equipment and pack, including his wallet and many of his belongings. They were all destroyed in what was later named the Mustang Fire, which incinerated more than 300,000 acres in the Salmon-Challis National Forest.

Golden was a temporary seasonal forestry technician at the time and never received treatment for what he thinks could be post-traumatic stress. He took just one day off to order a new bank card and was back at work the next day. When he tried to talk to his supervisor about the experience, he was told to move on: “You might as well forget about it.”

Missing birthdays and other special events is one of the many drawbacks wildland firefighters like Jonathon Golden face.

Courtesy of Jonathon Golden

Golden is just one of thousands of federal wildland firefighters who work six months out of the year and whose part-time status doesn’t come with the typical benefits or job security given to state and city firefighters.

NBC News spoke with 27 current and former USFS firefighters with similar stories. Nearly all of them said they are grossly underpaid to perform life-threatening work. Many don’t have access to health care and other benefits, particularly during the off-season. They are not even considered to be firefighters, instead falling into a bureaucratic quagmire that designates them as forestry technicians. Some grimly joke that only in death does the agency recognize them as bona fide firefighters.

“It takes us dying to get their attention,” said Riva Duncan, a forest management officer.

Despite the low pay and benefits, many wildland firefighters said they can’t imagine a life outside fire. For some, the adrenaline rush becomes a kind of compulsion. For others, sleeping under the stars and protecting federal land is a higher calling.

“For those of us who stick it out, our love for what we do outweighs everything,” said Duncan, who has been with the USFS for 37 years. “The sacrifices we have made — it’s because we believe in the mission.”

Amid escalating fire threats fueled by climate change and forest mismanagement, these workers are now organizing and lobbying Congress in new ways. They are finding bipartisan support among some Western lawmakers, but many worry the federal agency that employs them is ill-equipped to provide adequate pay and benefits despite the dangerous nature of their jobs.

Golden is just one of thousands of federal wildland firefighters who work six months out of the year and whose part-time status doesn’t come with the typical benefits or job security given to state and city firefighters.

NBC News spoke with 27 current and former USFS firefighters with similar stories. Nearly all of them said they are grossly underpaid to perform life-threatening work. Many don’t have access to health care and other benefits, particularly during the off-season. They are not even considered to be firefighters, instead falling into a bureaucratic quagmire that designates them as forestry technicians. Some grimly joke that only in death does the agency recognize them as bona fide firefighters.

“It takes us dying to get their attention,” said Riva Duncan, a forest management officer.

Despite the low pay and benefits, many wildland firefighters said they can’t imagine a life outside fire. For some, the adrenaline rush becomes a kind of compulsion. For others, sleeping under the stars and protecting federal land is a higher calling.

“For those of us who stick it out, our love for what we do outweighs everything,” said Duncan, who has been with the USFS for 37 years. “The sacrifices we have made — it’s because we believe in the mission.”

Amid escalating fire threats fueled by climate change and forest mismanagement, these workers are now organizing and lobbying Congress in new ways. They are finding bipartisan support among some Western lawmakers, but many worry the federal agency that employs them is ill-equipped to provide adequate pay and benefits despite the dangerous nature of their jobs.

A plane drops repellant on a forest fire Jonathon Golden was fighting.

Jonathon Golden

According to the Congressional Research Service, as of Oct. 1, over 44,000 wildfires have burned nearly 7.7 million wildland acres this year alone. That’s more than 12,000 square miles, or an area about 1 1/2 times the size of New Jersey.

Over the last decade, fire seasons have gradually turned into fire years. This year, more than 4 million acres have already burned in California alone, forcing thousands of evacuations and power outages across the state. Longer-burning fires have also resulted in more dangerous work. In September, a Hotshot squad leader was killed battling the El Dorado Fire in San Bernardino County, California.

The USFS declined to make anyone in leadership available for an interview and did not directly address many of NBC News’ detailed questions.

Babete Anderson, a spokeswoman for the USFS, said in a statement that the agency is “working to identify solutions by listening to our firefighters to ensure their needs are met.”

“We need to treat the landscape at a much larger scale, 2-3 times what we do now, together with our partners,” she wrote. “Only then will we significantly reduce the threat of wildfire to communities, ensure our forests endure into the future and provide firefighters the safe spaces they need to respond.”

According to the Congressional Research Service, as of Oct. 1, over 44,000 wildfires have burned nearly 7.7 million wildland acres this year alone. That’s more than 12,000 square miles, or an area about 1 1/2 times the size of New Jersey.

Over the last decade, fire seasons have gradually turned into fire years. This year, more than 4 million acres have already burned in California alone, forcing thousands of evacuations and power outages across the state. Longer-burning fires have also resulted in more dangerous work. In September, a Hotshot squad leader was killed battling the El Dorado Fire in San Bernardino County, California.

The USFS declined to make anyone in leadership available for an interview and did not directly address many of NBC News’ detailed questions.

Babete Anderson, a spokeswoman for the USFS, said in a statement that the agency is “working to identify solutions by listening to our firefighters to ensure their needs are met.”

“We need to treat the landscape at a much larger scale, 2-3 times what we do now, together with our partners,” she wrote. “Only then will we significantly reduce the threat of wildfire to communities, ensure our forests endure into the future and provide firefighters the safe spaces they need to respond.”

Low pay, few benefits

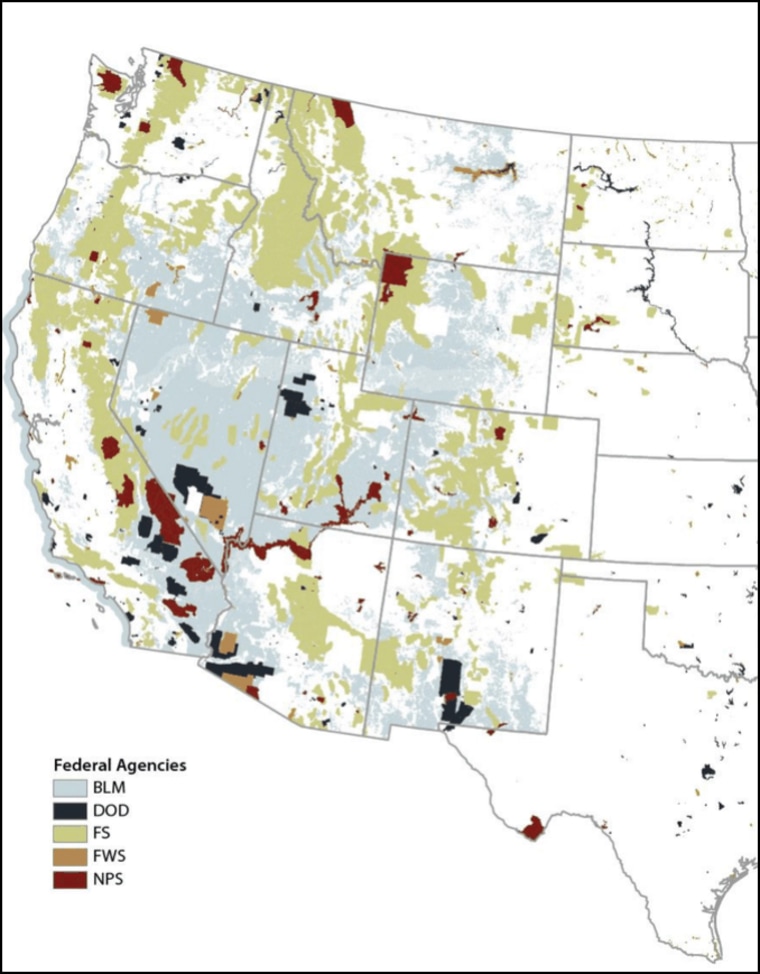

It’s difficult to fully appreciate how large the American West is, and most don’t realize how much of it is federally owned and managed. Most states west of Kansas have substantial portions of their territory controlled by the federal government.

The U.S. Forest Service, which operates under the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is responsible for roughly 30 percent of all federal land: 193 million acres, or over 301,000 square miles, the overwhelming majority of it in the West. The total area of USFS-managed land is larger than the entire state of Texas by approximately 30,000 square miles.

Western federal lands managed by five agencies.

Congressional Research Service

To oversee all of that land, and the 28,000 employees that work on it, the agency has an annual budget of $5.3 billion. Nearly half ($2.4 billion) of that budget is currently spent on “wildland fire management.” A 2015 USFS report estimated this cost will rise to over two-thirds of the agency’s annual budget by 2025, to the detriment of nearly all other agency priorities, including vegetation and watershed management, facilities maintenance and more.

Every fire season, in the spring, USFS ramps up and hires an additional 12,000 seasonal employees, hired primarily for firefighting, most of whom have to reapply for their job each season.

This seasonal employment model is one that many younger firefighters who spoke with NBC News lament: In the off-season, they seek work in fields as diverse as construction to farming to photography, and some even receive unemployment benefits.

In the parlance of the agency, the bulk of the USFS firefighters are “1039s,” referring to the number of work hours they are capped at in a given season. That is just a single hour shy of six months of paid work, which means the federal government can classify those workers as temporary. They are not able to receive automatic health care, retirement or other benefits afforded to permanent employees.

In practice, firefighters battling an active fire often end up working well beyond the 1,039 base hours with overtime, sometimes accruing up to additional 1,000 hours.

One current forest service employee, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, said his low pay means he sometimes can’t afford basic necessities for his kids.

“I struggle to put new shoes on my children as a temporary firefighter,” he said. “I had to look at my 6-year-old and tell her I couldn’t afford brand-new shoes for her while we were shopping at a thrift store after a complete season of firefighting.”USFS firefighter pay is dictated by the federal pay scale, where most start at the GS-3 level and where pay tops out at around $31,000 annually for full-time employees. By comparison, a first-year firefighter with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, better known as Cal Fire, makes nearly double that amount.

Most rank-and-file temporary seasonal workers are starting at an hourly base salary of approximately $13 per hour plus overtime and hazard pay. One current USFS firefighter posted to Reddit recently showing that after eight years of service his gross pay topped out at around $30,000 annually.

“What the federal government is doing is asking 20-year-olds to risk their lives for $13 to $15 and say, ‘Sayonara,’ with no retirement benefits, nothing,” said Brandon Dunham, a former USFS and Bureau of Land Management firefighter. “That is a human tragedy right there.”

To oversee all of that land, and the 28,000 employees that work on it, the agency has an annual budget of $5.3 billion. Nearly half ($2.4 billion) of that budget is currently spent on “wildland fire management.” A 2015 USFS report estimated this cost will rise to over two-thirds of the agency’s annual budget by 2025, to the detriment of nearly all other agency priorities, including vegetation and watershed management, facilities maintenance and more.

Every fire season, in the spring, USFS ramps up and hires an additional 12,000 seasonal employees, hired primarily for firefighting, most of whom have to reapply for their job each season.

This seasonal employment model is one that many younger firefighters who spoke with NBC News lament: In the off-season, they seek work in fields as diverse as construction to farming to photography, and some even receive unemployment benefits.

In the parlance of the agency, the bulk of the USFS firefighters are “1039s,” referring to the number of work hours they are capped at in a given season. That is just a single hour shy of six months of paid work, which means the federal government can classify those workers as temporary. They are not able to receive automatic health care, retirement or other benefits afforded to permanent employees.

In practice, firefighters battling an active fire often end up working well beyond the 1,039 base hours with overtime, sometimes accruing up to additional 1,000 hours.

One current forest service employee, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, said his low pay means he sometimes can’t afford basic necessities for his kids.

“I struggle to put new shoes on my children as a temporary firefighter,” he said. “I had to look at my 6-year-old and tell her I couldn’t afford brand-new shoes for her while we were shopping at a thrift store after a complete season of firefighting.”USFS firefighter pay is dictated by the federal pay scale, where most start at the GS-3 level and where pay tops out at around $31,000 annually for full-time employees. By comparison, a first-year firefighter with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, better known as Cal Fire, makes nearly double that amount.

Most rank-and-file temporary seasonal workers are starting at an hourly base salary of approximately $13 per hour plus overtime and hazard pay. One current USFS firefighter posted to Reddit recently showing that after eight years of service his gross pay topped out at around $30,000 annually.

“What the federal government is doing is asking 20-year-olds to risk their lives for $13 to $15 and say, ‘Sayonara,’ with no retirement benefits, nothing,” said Brandon Dunham, a former USFS and Bureau of Land Management firefighter. “That is a human tragedy right there.”

U.S. Forest Service firefighters monitor a back fire while battling to save homes at the Camp Fire in Paradise, Calif., on Nov. 8, 2018.Stephen Lam / Reuters file

Dunham and others recently sent a letter to top senators seeking to “advocate for fair pay and wage equality,” among other requests for their ilk.

The former “helitack” crew member — a type of wildland firefighter specializing in helicopter operations — has given up firefighting after 11 years, in favor of working construction, spending more time at home with his wife and hosting a podcast by and for wildland firefighters called “The Anchor Point Podcast.” He decided to leave the field as he felt there was no future for him there.

When asked if he would like to return to wildland firefighting, with an agency like Cal Fire, Dunham did not hesitate.

“I would go jump on a Cal Fire engine in a heartbeat,” he said.

Larger fires, increasing demand

The Reno, Nevada, resident left the USFS at a time when, according to a recent report from the Congressional Research Service, an average of nearly 7 million acres of federal land has burned every year since 2000, more than double the average annual acreage burned during the 1990s.

Beginning in the USFS 2019 Budget Justification document, even the USFS itself began remarking on the fact that there is now “year-round fire activity” rather than a traditional fire season. “

Dunham and others recently sent a letter to top senators seeking to “advocate for fair pay and wage equality,” among other requests for their ilk.

The former “helitack” crew member — a type of wildland firefighter specializing in helicopter operations — has given up firefighting after 11 years, in favor of working construction, spending more time at home with his wife and hosting a podcast by and for wildland firefighters called “The Anchor Point Podcast.” He decided to leave the field as he felt there was no future for him there.

When asked if he would like to return to wildland firefighting, with an agency like Cal Fire, Dunham did not hesitate.

“I would go jump on a Cal Fire engine in a heartbeat,” he said.

Larger fires, increasing demand

The Reno, Nevada, resident left the USFS at a time when, according to a recent report from the Congressional Research Service, an average of nearly 7 million acres of federal land has burned every year since 2000, more than double the average annual acreage burned during the 1990s.

Beginning in the USFS 2019 Budget Justification document, even the USFS itself began remarking on the fact that there is now “year-round fire activity” rather than a traditional fire season. “

The Nation is experiencing more extreme fire behavior and high risk, high cost wildfire suppression operations in the wildland-urban interface have progressively become the new normal over the last two decades,” the fiscal year 2021 document stated.

“It is estimated that 63 million acres of National Forest System lands and 70,000 communities are at risk from uncharacteristically severe wildfires. Annually, there are typically more than 5,000 fires on National Forest System lands.”

There is a rapidly increasing disconnect between the fiscal realities of firefighting (they are paid relatively little) and the ground truth: Fires are burning larger areas than ever before and these firefighters are in higher demand.

“The bureaucracy of the federal government does not match the speed with which fire is changing,” said one USFS firefighter based in Oregon who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal.

As fires have increased in frequency and intensity in recent years, fatalities among wildland firefighters have also increased. A 2014 Quadrennial Fire Review commissioned by the USFS and the Department of the Interior Office of Wildland Fire found that the 10-year moving average of wildland firefighter fatalities had nearly doubled in 40 years.

There is a rapidly increasing disconnect between the fiscal realities of firefighting (they are paid relatively little) and the ground truth: Fires are burning larger areas than ever before and these firefighters are in higher demand.

“The bureaucracy of the federal government does not match the speed with which fire is changing,” said one USFS firefighter based in Oregon who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal.

As fires have increased in frequency and intensity in recent years, fatalities among wildland firefighters have also increased. A 2014 Quadrennial Fire Review commissioned by the USFS and the Department of the Interior Office of Wildland Fire found that the 10-year moving average of wildland firefighter fatalities had nearly doubled in 40 years.

Juggling family and firefighting

Despite the increased fire threat, many wildland firefighters say they are not given the resources or protections necessary to continue working with the U.S. Forest Service year after year.

It took Mike West a decade to become a full-time employee with the agency and even then finding treatment for his PTSD was difficult.

“I had too many close calls,” he said. “I didn’t really want to be out in the field anymore.”

Mike West at the Gasquet Fire on the Six Rivers National Forest in 2015.

Courtesy of Mike West

In 2013, a childhood friend who worked as a smokejumper was killed by a limb from a burning tree. The loss devastated West and triggered an onslaught of symptoms — including anxiety, nightmares and depression — he later learned were caused by PTSD.

“I just sort of covered it up,” he said. “At the time I thought it would be weak if I said anything, so I didn’t tell anybody.”

Three years later the symptoms were worse. He developed short-term memory loss and decided to seek treatment through the USFS. The first counselor assigned to him did not have the necessary background to treat PTSD, West said. He found another doctor that could address his trauma but that therapist was located 90 miles away in Reno, Nevada.

For six months West made the commute, which only exacerbated problems at home. He had two small children that he rarely saw and a wife who grew increasingly tired of juggling child care and her own full-time job.

One night, after working an 18-hour shift as a dispatcher, West had enough.

“It got to the point where I had to choose: Do I want to be a good family man and a bad firefighter or do I want to be a really good firefighter and bad with my family? I couldn’t find a balance,” he said.

“More often than not, people leave because of the strain,” he added. “I don't know too many people who are married and still do the work.”

West finally resigned from the Forest Service in July after 17 years with the agency and became a teacher. His final pay scale as a dispatcher came out to $21.50 an hour plus overtime. In his resignation letter, West pointed to “systemic problems” within the service that made it impossible to continue working for the agency.

Among those problems is their classification as forestry technicians, instead of being fully recognized for their firefighting work.

“You’re a firefighter if you’re thinking about applying, a forestry technician while you’re fighting fires, and if you die you’re a firefighter again?” West wrote in the letter. "I didn’t want to risk my children growing up without a dad because I died fighting fire for an agency that didn’t even consider me a firefighter."

In 2013, a childhood friend who worked as a smokejumper was killed by a limb from a burning tree. The loss devastated West and triggered an onslaught of symptoms — including anxiety, nightmares and depression — he later learned were caused by PTSD.

“I just sort of covered it up,” he said. “At the time I thought it would be weak if I said anything, so I didn’t tell anybody.”

Three years later the symptoms were worse. He developed short-term memory loss and decided to seek treatment through the USFS. The first counselor assigned to him did not have the necessary background to treat PTSD, West said. He found another doctor that could address his trauma but that therapist was located 90 miles away in Reno, Nevada.

For six months West made the commute, which only exacerbated problems at home. He had two small children that he rarely saw and a wife who grew increasingly tired of juggling child care and her own full-time job.

One night, after working an 18-hour shift as a dispatcher, West had enough.

“It got to the point where I had to choose: Do I want to be a good family man and a bad firefighter or do I want to be a really good firefighter and bad with my family? I couldn’t find a balance,” he said.

“More often than not, people leave because of the strain,” he added. “I don't know too many people who are married and still do the work.”

West finally resigned from the Forest Service in July after 17 years with the agency and became a teacher. His final pay scale as a dispatcher came out to $21.50 an hour plus overtime. In his resignation letter, West pointed to “systemic problems” within the service that made it impossible to continue working for the agency.

Among those problems is their classification as forestry technicians, instead of being fully recognized for their firefighting work.

“You’re a firefighter if you’re thinking about applying, a forestry technician while you’re fighting fires, and if you die you’re a firefighter again?” West wrote in the letter. "I didn’t want to risk my children growing up without a dad because I died fighting fire for an agency that didn’t even consider me a firefighter."

‘A tipping point’

Communication breakdowns and department mismanagement have persisted for over a generation — and it’s frustrating the dwindling ranks of seasonal firefighters, as retirements are outpacing hiring. This is especially problematic at a time when wildland fires continue to burn larger, faster and stronger than ever before.

In April, 11 U.S. senators sent a letter to U.S. Forest Service Chief Vicki Christiansen warning that the confluence of Covid-19 and high levels of drought in many Western states could make for volatile firefighting conditions, including a 6 percent "'cumulative mortality rate' at large fire camps."

The warning was not passed down to those on the front lines. Instead, it was circulated among crews after someone found it on Reddit.

“I am more than happy to put my life in danger for the work that I do but it felt like a stab in the back,” a current wildland firefighter, who asked to remain anonymous, said.

Jonathon Golden and crew responding to a wildfire.

Courtesy Jonathon Golden

When asked about the breakdown in communication between USFS and its employees, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., who signed the letter, said, “I’m not just angry about that. I’m furious.”

“We’re going to get through this fire season, but we’re not going through another fire season where there is this kind of fragmented, poorly coordinated policy that our very own firefighters aren’t even getting adequate information from Washington, D.C.,” he said. “It’s unacceptable.”

The seasonality of the work, coupled with the low wages and risk, has made recruitment more difficult over the last two decades — and the government has done little to fix the problem.

In 1999, the Government Accountability Office told a House subcommittee it had found that the “firefighting workforces” of both the USFS and the Bureau of Land Management “are shrinking” as a result of retirement.

Over a decade later, the USDA’s Office of Inspector General, the department’s internal watchdog, reached a similar conclusion, warning of a wave of retirement without a corresponding increase in new hires.

In addition to the firefighter recruitment concerns, there’s also a budgetary shortfall for the agency to perform adequate year-round forest management work aimed at reducing wildfire risk.

In 2015, in a USFS paper, the agency warned that absent new large-scale funding, it had been forced to reallocate its budget toward firefighting and away from other priorities, concluding that the agency was now “at a tipping point.”

“As more and more of the agency’s resources are spent each year to provide the firefighters, aircraft, and other assets necessary to protect lives, property, and natural resources from catastrophic wildfires, fewer and fewer funds and resources are available to support other agency work—including the very programs and restoration projects that reduce the fire threat,” the paper stated.

Mike Rogers, a former Angeles National Forest supervisor and board member of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees, said forest management was originally the cornerstone of the agency’s work.

“Our workforce was never a fire department,” he said, underscoring that he began at the agency in 1957. “In the old days, everyone put out the fire when we had a fire but then we went back to our jobs and that was managing the forest. We didn’t have specialized firefighters.”

Despite these stark warnings, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, there has been little has been little substantial progress on increasing the Forest Service’s budget, nor has there been substantive movement on reclassification of forestry technicians as firefighters, expanding fuel reduction and other preventative efforts.

However, in a rare moment of bipartisanship, Sen. Steve Daines, R-Mont., collaborated with Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., on the Emergency Wildfire and Public Safety Act of 2020, which aims to reduce fire risk in their respective states.

In a recent letter to Senate leadership, the two senators had a dire warning.

“If we don’t take strong action now, we worry that what’s happening to California and Montana will soon become the new normal in every state in the West,” they wrote.

Cyrus Farivar is a reporter on the tech investigations unit of NBC News in San Francisco.

Alicia Victoria Lozano is a Los Angeles-based digital reporter for NBC News.

When asked about the breakdown in communication between USFS and its employees, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., who signed the letter, said, “I’m not just angry about that. I’m furious.”

“We’re going to get through this fire season, but we’re not going through another fire season where there is this kind of fragmented, poorly coordinated policy that our very own firefighters aren’t even getting adequate information from Washington, D.C.,” he said. “It’s unacceptable.”

The seasonality of the work, coupled with the low wages and risk, has made recruitment more difficult over the last two decades — and the government has done little to fix the problem.

In 1999, the Government Accountability Office told a House subcommittee it had found that the “firefighting workforces” of both the USFS and the Bureau of Land Management “are shrinking” as a result of retirement.

Over a decade later, the USDA’s Office of Inspector General, the department’s internal watchdog, reached a similar conclusion, warning of a wave of retirement without a corresponding increase in new hires.

In addition to the firefighter recruitment concerns, there’s also a budgetary shortfall for the agency to perform adequate year-round forest management work aimed at reducing wildfire risk.

In 2015, in a USFS paper, the agency warned that absent new large-scale funding, it had been forced to reallocate its budget toward firefighting and away from other priorities, concluding that the agency was now “at a tipping point.”

“As more and more of the agency’s resources are spent each year to provide the firefighters, aircraft, and other assets necessary to protect lives, property, and natural resources from catastrophic wildfires, fewer and fewer funds and resources are available to support other agency work—including the very programs and restoration projects that reduce the fire threat,” the paper stated.

Mike Rogers, a former Angeles National Forest supervisor and board member of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees, said forest management was originally the cornerstone of the agency’s work.

“Our workforce was never a fire department,” he said, underscoring that he began at the agency in 1957. “In the old days, everyone put out the fire when we had a fire but then we went back to our jobs and that was managing the forest. We didn’t have specialized firefighters.”

Despite these stark warnings, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, there has been little has been little substantial progress on increasing the Forest Service’s budget, nor has there been substantive movement on reclassification of forestry technicians as firefighters, expanding fuel reduction and other preventative efforts.

However, in a rare moment of bipartisanship, Sen. Steve Daines, R-Mont., collaborated with Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., on the Emergency Wildfire and Public Safety Act of 2020, which aims to reduce fire risk in their respective states.

In a recent letter to Senate leadership, the two senators had a dire warning.

“If we don’t take strong action now, we worry that what’s happening to California and Montana will soon become the new normal in every state in the West,” they wrote.

Cyrus Farivar is a reporter on the tech investigations unit of NBC News in San Francisco.

Alicia Victoria Lozano is a Los Angeles-based digital reporter for NBC News.

No comments:

Post a Comment