NEW ZEALAND THE SEVENTIES

The dawn raids explained: What drove the Government to target Pasifika peopleKeith Lynch Aug 01 2021

Once a Panther is a Stuff podcast about the Polynesian Panther Party, a group of young New Zealand-born Pacific Islanders who stood up to institutionalised racism and helped change the course of history in Aotearoa.

In the 1970s, New Zealand governments (both Labour and National), migration officials and police targeted Pasifika overstayers. Homes were raided late at night and people were stopped in the street.

What happened has prompted a formal apology from Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s government, which will take place in Auckland today.

This is what led to the raids and how they came to an end.

The boom

In 1945, there were about 2000 Pasifika people living in New Zealand.

READ MORE:

* A Dawn Raids apology is worthless without an overstayer amnesty, says 'Tongan Robin Hood'

* Dawn raids on overstayers still happening, despite Government apology to Pasifika

After World War II, Aotearoa’s economy enjoyed an unprecedented boom, fuelled mostly by agricultural exports – the likes of meat, wool and dairy – primarily to Britain. Wool was particularly lucrative.

These industries needed workers, so the Government actively sought to attract people from a range of nearby Pacific countries. Most arrived from the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji.

At the time, those from the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau were automatically granted New Zealand citizenship which, of course, meant they could come and go as they pleased. (This changed in 2006).

Those from Tonga, Samoa and Fiji were not citizens. But they were still granted access to New Zealand through the likes of temporary short-term visas and other migration schemes.

According to this Te Ara piece: “Programmes brought young men over as agricultural and forestry workers, and young women as domestics.”

ROBERT KITCHIN/STUFF

Minister Aupito William Sio gets emotional during the press conference as he talked about his Dawn Raid experiences.

By 1976, there were almost 65,700 Pasifika people in the country, 2.1 per cent of the total population.

As New Zealand badly needed workers, it essentially turned a blind eye to Pasifika people coming into the country and staying on when a visa expired.

The bust

Life was pretty good in 1960s New Zealand. The country had a high standard of living. Nearly everyone had a job and there was almost no inflation.

Then came December 14, 1966, when the auction price for wool collapsed by 40 per cent overnight. It caused a 16 per cent drop off in our export revenue, according to this Radio New Zealand report.

On January 1, 1973, Britain joined the European Economic Community, which has since morphed into the European Union. This severely impacted a New Zealand economy reliant on exports. The terms of the game had changed.

Worse was to come. The price of oil soared, rising from about US$3 a barrel to nearly US$20 in the early 1970s. The hikes were prompted by Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposing an embargo on oil production, retaliating against western nations for supporting Israel in the 1973 war. Higher oil prices made it more expensive to do business.

These economic shocks rocked New Zealand to its core.The good times were over. Jobs were harder to come by. And some media and politicians began to demonise certain groups of people.

The blame

A 1968 amendment to the Immigration Act helped lay the groundwork of what was to come. The law change allowed the deportation of those who had overstayed their work permits. It also required people to produce a work permit or passport to prove their immigration status, if asked.

If you didn’t have a passport you were in trouble. The problem was, as Joris de Bres, a former Race Relations Commissioner, wrote: “Often, their passports were held by travel agents as a bond against repayment of their borrowed fares.”

Dr Melani Anae, an associate professor of Pacific studies at the University of Auckland, explained what this meant in her book: The Platform: The Radical Legacy of the Polynesian Panthers. (This excerpt was published on E-Tangata.)

“Those who did not comply on the spot could be arrested, kept in a holding cell without a warrant, and in some cases deported…”

The law allowed officials to target Samoan and Tongan people who stayed on after their permit expired. Police also created task forces targeting overstayers and dealing with violence in inner-city Auckland.

Massey University’s Professor Paul Spoonley says the Labour government of the time was unusual and somewhat divided on the issue. On one hand, they made conciliatory remarks about the Pacific. On the other hand, they ordered a crackdown on overstayers.

In 1974, the year before New Zealand's next general election, the raids began.

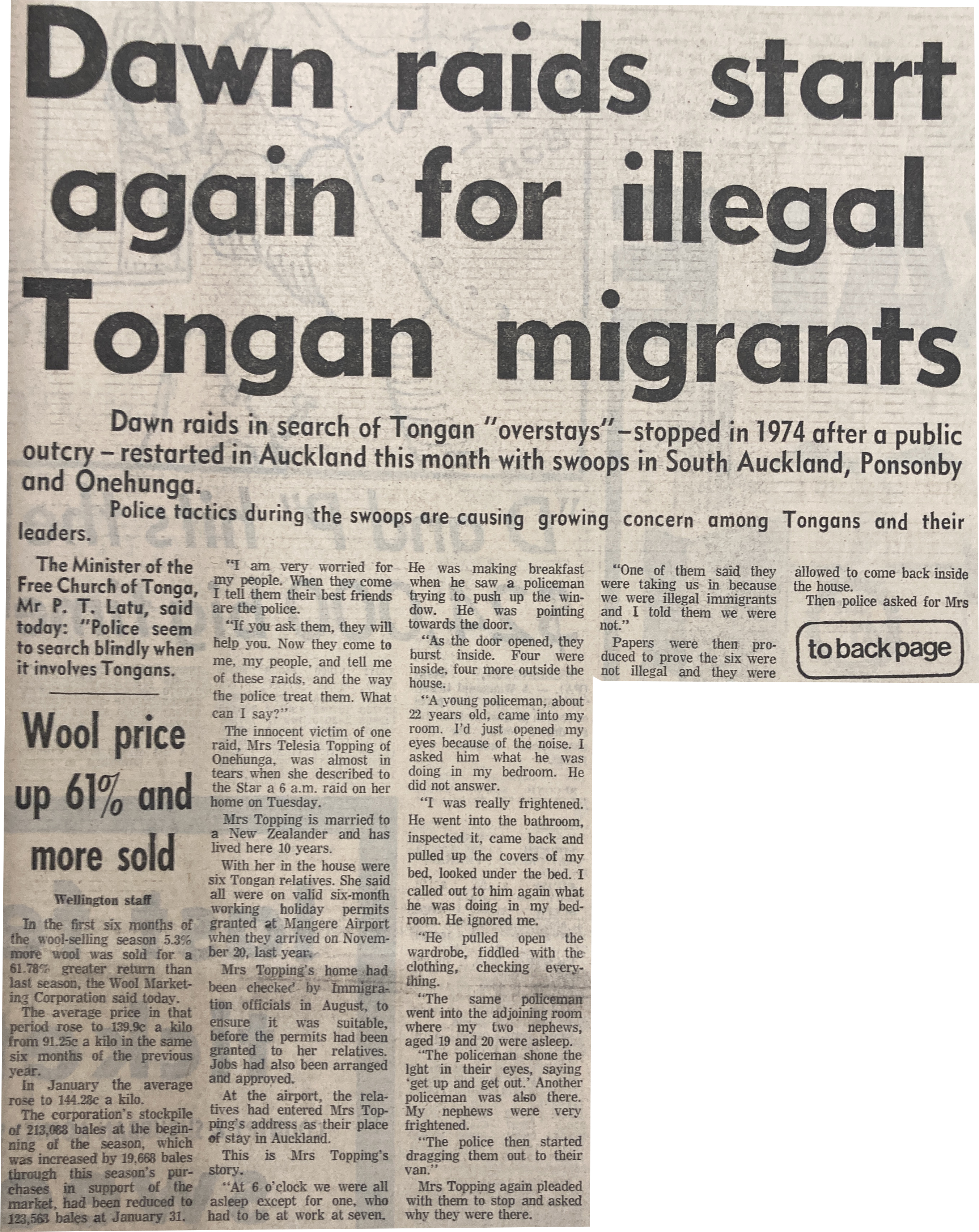

SUPPLIED.

Telesia Topping tells her story during the Dawn Raids.

The raids

A young policeman, about 22 years old, came into my room . . . I asked him what he was doing in my bedroom. He did not answer. I was really frightened.

He went to the bathroom, inspected it, came back and pulled the covers off my bed . . . He pulled open the wardrobe, fiddled with the clothing, checked everything. The same policeman went into the adjoining room where my two nephews, aged 19 and 20 years, were asleep. The policeman shone the light into their eyes, saying “get up and get out”...

My nephews were very frightened. The police then started dragging them out to their van.

This was the account of Telesia Topping, a Tongan woman who had lived in New Zealand for 10 years. She told the story to the Auckland Star.

Police and immigration officials targeted Pasifika people in a bid to remove alleged overstayers. They went to homes and churches, and targeted factories and hotels. They used dogs. New Zealand citizens were, of course, also caught up in the raids.

The election

Spooked by protests and potentially realising the economic necessity of migrants, Labour acted. Immigration Minister Fraser Colman called a halt to the raids in 1974. Prime Minister Norman Kirk introduced an amnesty allowing migrants to register themselves and gain a two-month extension of their work visa. Kirk died later that year.

Labour’s shift was seized upon by the National Party, led by Robert Muldoon. He took the party leadership in July 1974 and immediately promised to cut migration. His rhetoric was populist and nationalistic.

The National Party ran an extremely controversial campaign ad, animated by Hanna-Barbera (which was behind Scooby Doo and The Flintstones) directed at migrants.

SUPPLIED

A still from National's controversial campaign cartoon before the 1975 election.

Muldoon won and the raids became more intense in 1975. Now people were being randomly stopped in the streets.

When asked about whether the police were targetting Pasifika people, the then Police Minister Allan McCready said they were not. He explained: “If you have a herd of Jerseys and two Friesians, the Friesians stand out.”

News reports also emerged that some police were angry at being used as political pawns. The Government’s position was simple. The raids were justified to catch illegal migrants.

The Polynesian Panthers

An activist group called the Polynesian Panthers was formed in 1971 to fight discrimination. They grew throughout the 1970s with members in Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin and Sydney.

As Stuff’s Brad Flahive and Alex Liu reported, the Panthers responded to the raids by supporting their community but also by “raiding” government ministers outside their homes in the early hours of the morning.

The group has gone on to successfully campaign for a state apology, which will happen at a commemoration event in the Auckland Town Hall on August 1.

***To mark the party’s 50th anniversary, Stuff released its latest major podcast funded by NZ On Air. Once a Panther chronicles their stories. You can find it here.

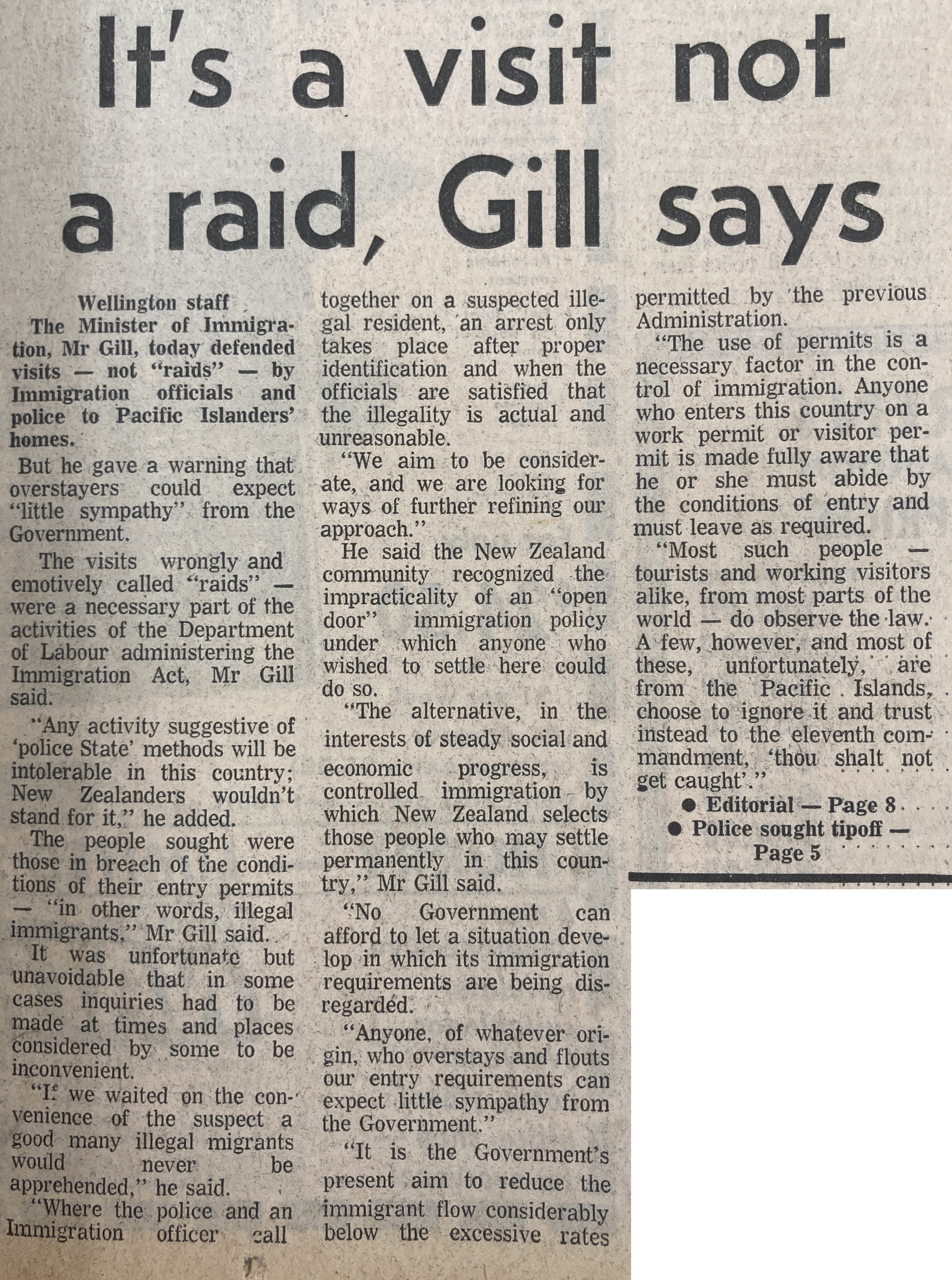

SUPPLIED.

The Immigration Minister defended the raids

.

The wind-down

Ultimately the raids became untenable. In 1977, the Immigration Department changed up overstayers' processes.

The NZ History website provides an insight into the political motivations that ended the raids.

While some point to the work of the Polynesian Panthers and other advocacy groups, author Sharon Alice Liava'a believed the public condemnation of the raids did not in fact lead to them coming to the end.

“Rather, she claims that it was Muldoon’s own realisation that things had gone too far that led to the raids ending," reported NZ History.

There were also tangible economic changes. While the police went after Pasifika people, the economy wasn’t getting much better. And in 1977 people were leaving New Zealand – about 12,000 a year.

The public, business leaders and trade unionists were not necessarily happy with this.

“The Government came under pressure from employers, many of whom had stayed silent during the campaign, even though they had been directly benefiting from Pasifika labour,” Spoonley said.

KEITH LYNCH • EXPLAINER EDITOR

keith.lynch@stuff.co.nz

The data

This Canterbury University thesis cites a 1977 computer printout of expired visitors and work permits that showed that “of the 3641 persons who stayed beyond their allotted time in the preceding 12 months, 40 per cent of them were other than Pacific Islanders”.

According to the then Immigration Minister Frank Gill, the reasons Samoan, Tongan and Fijian people were targeted was because they “tell tales on each other” and were easy to detect as they worked.

Spoonley’s book Racism and Ethnicity outlines that the “discriminatory” behaviour continued after the raids.

Between August 1, 1985, and March 31, 1986, there were 313 prosecutions against illegal migrants.

“Although Pacific Island overstayers only constituted one-third of all overstayers, 86 per cent (270) of prosecutions involved Pacific Islanders. Overstayers from the US and UK comprised 31 per cent of all overstayers, but only 5 per cent of those prosecuted.”

Stuff contacted Immigration New Zealand to source numbers that would better illustrate the disproportionate targeting of Pasifika people. The data was not available.

In her formal statement announcing the raids, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said: “There is clear evidence the raids were discriminatory and have had a lasting negative impact.”

The first five episodes of Once a Panther can be found on Stuff or through podcast apps, including Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or via an RSS feed.

The wind-down

Ultimately the raids became untenable. In 1977, the Immigration Department changed up overstayers' processes.

The NZ History website provides an insight into the political motivations that ended the raids.

While some point to the work of the Polynesian Panthers and other advocacy groups, author Sharon Alice Liava'a believed the public condemnation of the raids did not in fact lead to them coming to the end.

“Rather, she claims that it was Muldoon’s own realisation that things had gone too far that led to the raids ending," reported NZ History.

There were also tangible economic changes. While the police went after Pasifika people, the economy wasn’t getting much better. And in 1977 people were leaving New Zealand – about 12,000 a year.

The public, business leaders and trade unionists were not necessarily happy with this.

“The Government came under pressure from employers, many of whom had stayed silent during the campaign, even though they had been directly benefiting from Pasifika labour,” Spoonley said.

KEITH LYNCH • EXPLAINER EDITOR

keith.lynch@stuff.co.nz

The data

This Canterbury University thesis cites a 1977 computer printout of expired visitors and work permits that showed that “of the 3641 persons who stayed beyond their allotted time in the preceding 12 months, 40 per cent of them were other than Pacific Islanders”.

According to the then Immigration Minister Frank Gill, the reasons Samoan, Tongan and Fijian people were targeted was because they “tell tales on each other” and were easy to detect as they worked.

Spoonley’s book Racism and Ethnicity outlines that the “discriminatory” behaviour continued after the raids.

Between August 1, 1985, and March 31, 1986, there were 313 prosecutions against illegal migrants.

“Although Pacific Island overstayers only constituted one-third of all overstayers, 86 per cent (270) of prosecutions involved Pacific Islanders. Overstayers from the US and UK comprised 31 per cent of all overstayers, but only 5 per cent of those prosecuted.”

Stuff contacted Immigration New Zealand to source numbers that would better illustrate the disproportionate targeting of Pasifika people. The data was not available.

In her formal statement announcing the raids, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said: “There is clear evidence the raids were discriminatory and have had a lasting negative impact.”

The first five episodes of Once a Panther can be found on Stuff or through podcast apps, including Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or via an RSS feed.

SEE

No comments:

Post a Comment