Huda Shaka, Jeddah.

6 December 2021

Around the world, urban planning is inextricably linked to both historic and current power structures. Urban planning in Palestine over the past century is no exception. Perhaps what differentiates Palestine today is the ongoing settler colonialization.Urban planning often serves existing power structures to the detriment of the marginalized and as such has been used as a tool for racial segregation and discrimination in many contexts. As UCLA Professor Ananya Roy puts it: “Urban planning has repeatedly produced segregation and displacement”. Much has been written, for example, on the discriminatory urban planning practices in the United States and their impact on exacerbating racial injustices against African Americans, in particular.

Yet, even as a planning professional of Palestinian origin who has visited the occupied West Bank many times and witnessed and experienced the discrimination against Palestinians there firsthand, the extent of the influence of planning policy was not obvious to me until I began researching it. Spatial planning policies, systematically introduced and enforced over the past century first by the British Mandate and then the Israeli government, have been instrumental in creating the unjust physical realities experienced by Palestinians today.

Below, I provide a glimpse of this planning history, which is vitally important to understanding today’s reality. I do this by highlighting excerpts from some of the research and scholarly work on this topic. The rest of this essay is organized mostly chronologically to address each of the key periods of the past century, with a final section focusing on the city of Jerusalem.

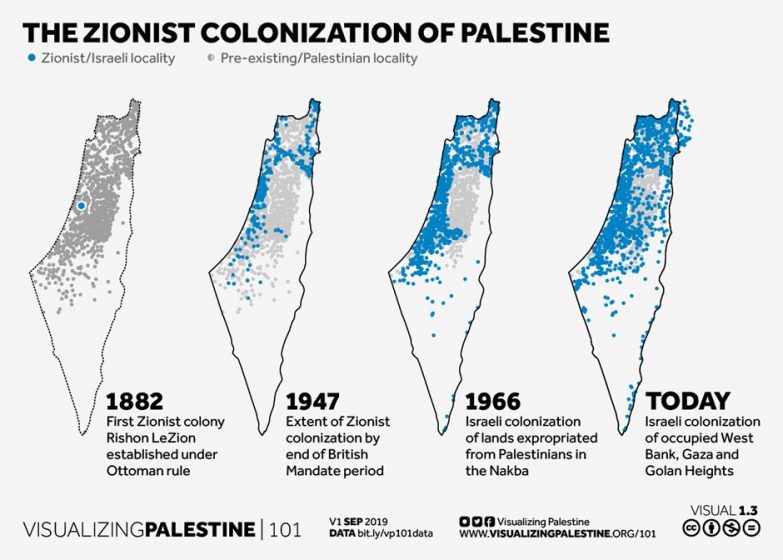

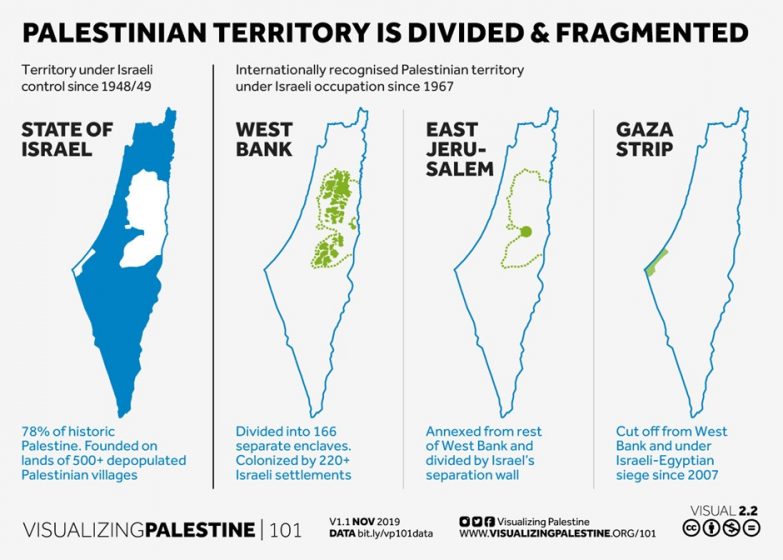

While this essay focuses on the planning history, I have provided brief commentary and infographics connecting to the wider context and broader history. For further reading on this history as told and experienced by the occupied (not the occupier), I recommend sources like Decolonise Palestine and Palestine Remembered. For a visual representation of how the creation of the State of Israel physically transformed Palestinian cities and villages, I highly recommend this excellent project by Visualizing Palestine.

Planning during the British Mandate (1920 – 1947)

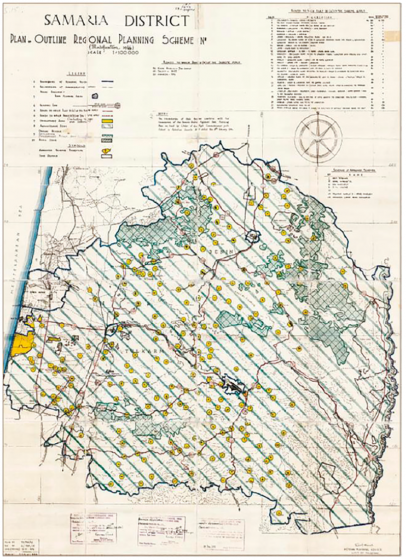

After the defeat of the Ottomans in World War I, Palestine came under the control of the British government. As Martin Crookston, a contemporary British planner, describes in this review, the plans developed by the British under this mandate did not even record all the existing Palestinian villages, let alone plan for their development or expansion to meet the future needs of the indigenous population (as is normal practice). What is even more shocking is that these plans are still in use today by the Israeli government.

“The map below indicates in yellows circles the villages. But the Plans did not record all the villages in 1940s Palestine; so these yellow circles do not represent a complete picture of rural settlement even then. There was intended to be a layer of more local planning below these ‘regional’ plans, but it never really happened, or only to a tiny extent. In the whole of Mandate Palestine, some 900 Arab villages saw only 25 outline plans prepared for them – eight of them in what is now the West Bank.”

A British Mandate Plan for part of Historic Palestine (1947). Source: Martin Crookston (2017) Echoes of Empire: British Mandate planning in Palestine and its influence in the West Bank today, Planning Perspectives, 32:1, 87-98, DOI:10.1080/02665433.2016.1213183

Furthermore, as is typical with the international transfer of planning expertise, British planners brought with them planning solutions which may have worked in Britain but did not necessarily work in Palestine. Crookston elaborates below:

“The echoes of empire ring down to the present in other ways in the Mandate Plans, too… Importing a ‘solution’ intended to tackle the sprawl that was stretching along the radial roads of UK cities, the plans declared wide building-lines to set development well back from primary roads. These are now cited as reasons for demolitions. And the regional plans’ zoning of areas for only a few main uses (roads, an agricultural zone, development zones, nature/forest reserves, and beach reserves) has become a tool for hyper-restriction of natural village expansion.”

In other words, British planning policies which were meant to restrict linear sprawl of town and cities in 20thcentury Britain were imposed on Palestinian villages and are now being used as legal justification for restricting the natural growth of these villages. Critically, the same planning policies were not applied to the Jewish colonies being set up by international Zionist organisations to accommodate hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants, who came mostly from Europe and the United States with no immediate ties to the land of Palestine. Not only were these colonies permitted, but they were also allowed to grow and develop without planning requirements or restrictions.

Rassem Khamaisi, professor at the University of Haifa, describes this dichotomy in applying planning policies as follows in his paper on the British Mandate and the control of Palestinians:” The Arabs were subject to restrictive statutory and physical planning, and land surveys were used as a tool for confiscating their land, particularly in situations of ethnic conflict.

By comparison, new Jewish colonies and towns were rapidly developing to absorb largescale Jewish immigration that came to Palestine, especially after the Second World War. The Mandate planning institutions did not involve approved structure plans for the Jewish agriculture colonies. Besides which, most employees in the Planning Adviser’s office and in the district commissions were Jewish, and some of them paid more attention to the Jewish towns plans than to the implementation of the Mandate policy.”

The Creation of the State of Israel over Palestinian villages (1948 – 1967)

Between 1947 and 1948, to enable the creation of a Jewish state, 750,000 Palestinians were made to flee their homes through violent assaults first by militant Jewish groups and then by the newly formed Israeli state. This moment in history had a significant impact on all aspects of life for Palestinians, including the strength and connectivity of their cities. The quote below is from another work by Khamaisi focusing on the major Palestinian urban centers and how they were affected by the creation of the State of Israel.

“In 1947, the United Nations Assembly partitioned Palestine into two states, Arab and Jewish, under Resolution 181. The War of 1948 between the Arabs and the Jewish, as an aftermath of this resolution, lead (sic) to the establishment of a viable, functional sovereign Jewish state with Tel-Aviv its urban core. This urban core began to develop in the 1930’s even though the Israelis aspired to establish Jerusalem as its Political core after the War of 1948, and according to the Rhodes ceasefire agreement of 1949. The Arab Palestinian state failed to establish, with Palestinian territory outside the Israeli state fragmented into two units lacking territorial continuity. As a result of this war, known as “Nakba” [disaster] to the Palestinians, and territorial fragmentation, the normal growth of Palestinian cities and towns changed in the wake of the establishment of the State of Israel. Israel divided Mandate Palestine under Jordanian rule (West Bank, “WB”) and Egyptian administration (Gaza Strip, “GS”). Between 1948-1967 the Palestinians lost their urban centers in territories within the newly established Israel proper, and the urban centers outside Israel’s borders, ruled by foreign Arab States, remained relatively small and dependent on the Jordanian core and the Egyptian core, Amman and Cairo, respectively. Jerusalem, which had previously functioned as the

Palestinian core, was divided into West Jerusalem, under the sovereignty of the State of Israel, while East Jerusalem was under Jordanian sovereignty and dependent on Amman.” The catastrophic loss of the Nakba was also felt, perhaps even more painfully, in Palestinian villages, hundreds of which were wiped off the map:

“After May 15th 1948 the War expanded and Israeli forces took over portions of the territory that was set aside for the establishment of a Palestinian state through the Partition Plan and expelled much of the population that lived in these areas. By the end of the war approximately 750,000 Palestinians had been made refugees and between 500 and 600 Palestinian villages had been depopulated. Many of these communities were later destroyed.”

— Source: https://www.afsc.org/resource/palestinian-refugees-and-right-return

To cover the traces of these acts of ethnic cleaning, many of the sites of the destroyed villages were later designated by Israeli authorities as nature reserves or cultural sites:

“The razed grounds of 182 erstwhile Palestinian villages — almost half of the villages depopulated by Israel in 1948 — are today included within the boundaries of Israeli nature and recreation spaces: mainly national parks, nature reserves and Jewish National Fund (JNF) forests and parks. Most of the Palestinian villages were intentionally destroyed by Israel during and after the 1948 war or gradually dilapidated due to lack of official care as they were not considered heritage sites worthy of preservation. However, many of the villages were centered on ancient ruins, whose historical value led in some cases to declarations of national parks on the grounds of former villages. Similarly, villages near a natural spring were later classified by Israel as nature reserves or recreation areas; and, lastly, one of the goals behind the planting of some of the JNF forests in Israel — later turned into recreational areas — had been to obscure the remains of destroyed Palestinian villages.”

—Source: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/232332

The multiple layers of colonisation and appropriation involved in such acts of forestation over ruined villages are described piercingly by Liat Berdugo in her essay reflecting on the tree she planted as a child in Jerusalem at the age of six:

“So the planting of forests is a politically charged endeavor that links ecology and aesthetics to cultural survival. It is a way for Israeli Jews to say ‘we are here’… But more than that: it is a strategy for expropriating land. Prior to the declaration of Israeli statehood, the leaders of KKL-JNF [Kayemeth Le’Yisrael, also known as the Jewish National Fund] saw afforestation as ‘a biological declaration of Jewish sovereignty’ that could be used to set up ‘geopolitical facts’.”

She goes on to describe:

“A half-century later, it remains a public secret that at least 46 KKL-JNF forests are located on the ruins of former Palestinian villages. American Independence Park, where the names of foreign donors are etched on the Wall of Eternal Life, is superimposed on the villages of Allar, Dayr al-Hawa, Khirbat al-Tannur, Jarash, Sufla, Bayt ‘Itab, and Dayr Aban, which were captured, ‘depopulated’ of their 4,000 inhabitants, and razed by Israeli state actors in 1948.”

Berdugo also implicates the Israeli legal system which rejects claims of Palestinians to village sites after they have been forested:

“And the Israeli courts have determined that when a forest is grown on expropriated land, Palestinians who return to that land are trespassing. In 2010, the Supreme Court rejected a petition by Palestinian refugees from the village of al-Lajjun to reclaim land in the Megiddo forest, ruling that afforestation justified Israeli control under the Land Acquisition Law of 1953.”

Planning during the military occupation of the West Bank (1967 – 1994)

Planning process in Palestinian centres

In 1967, Israel occupied the remainder of historic Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza). As an occupying power, Israeli authorities now had direct control over planning laws in these areas.

Rassem Khamaisi describes how the Israeli state took away agency and representation in planning from the indigenous Palestinian population through the issuance and implementation of Military Order (MO) 148 which transferred planning powers from local village councils to commissions appointed by the Israeli military:

“The MO no. 418 also abolished the local planning commission in village councils, later establishing six Regional Rural Planning Committees (RRPC). It also granted the Military Commander the authority to appoint members of the HPC [Higher Planning Commission] and RRPC. Under the MO, the HPC was also authorized to set up subsidiary or ad hoc committees as it deemed necessary. Once the MO had been issued and implemented, the Palestinians were robbed of all authority and responsibility in the planning institutions; their presence in the province and RRPC, or in the sub-commission of the HPC, was merely formal. The ‘responsible’ in charge set up the HPC and appointed Jewish members with no Palestinian representation.”

In this new planning system, most Palestinian applications for detailed plans or building permits were rejected on the pretence of protecting agricultural land or lack of sufficient land ownership documentation. This is captured in numbers by Khamaisi:

“Thus, obtaining a building permit was a very complicated and serious process, which decreased the number of building permits issued to the Palestinians. For example, in the period between 1 January 1988–1 September 1988, the number of applications submitted was 994, but the number of permits given was only 221. It is worth mentioning that in the period between 15 November 1986 and 28 September 1987 no permits at all were issued by the local committees.”

Establishment of new Jewish settlements

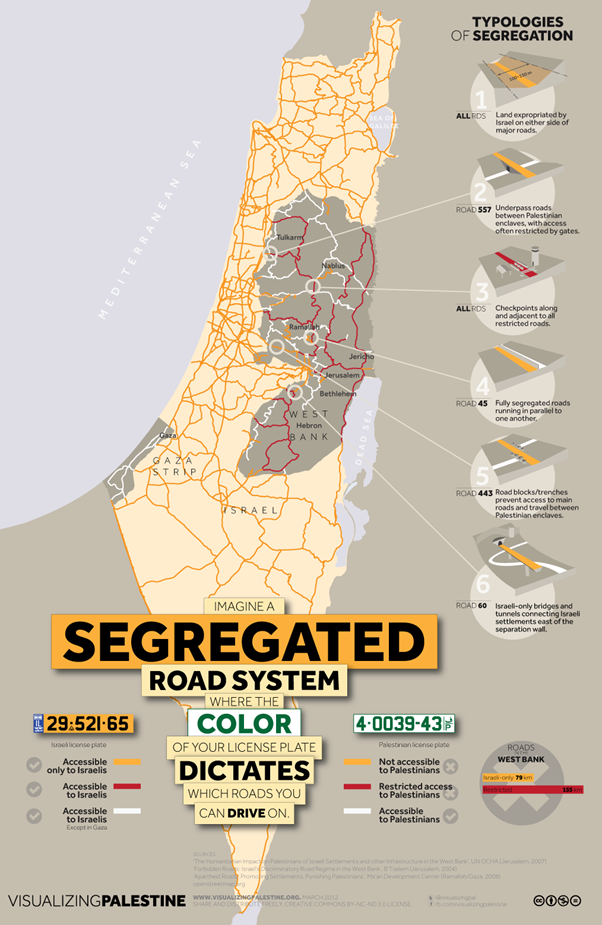

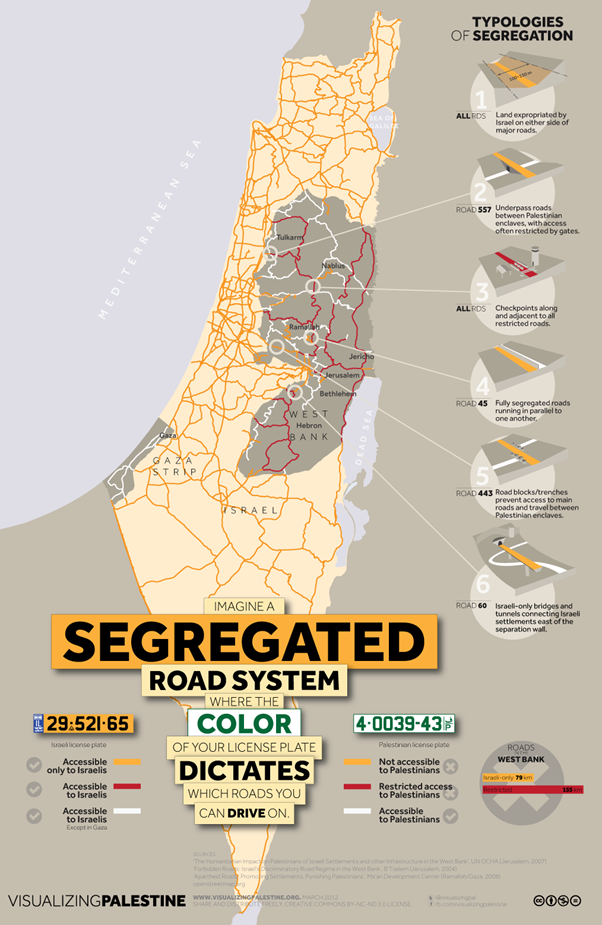

The HPC prepared regional plans for the West Bank in the early 1980s with multiple colonial objectives including limiting the development of Palestinian villages, severing connectivity of Palestinian cities, and most importantly enabling the establishment of Israeli settlements in the West Bank with full spatial segregation from Palestinians. In Khamaisi’s words:

“To amend the Mandate plans in the regional tier, the HPC prepared two regional plans covering part of the West Bank. The first, called the ‘Partial regional plan no. 1/82, amendment to regional plan RJ-5’, emerged in 1982. This plan covered an area of about 45 km2, around the three sides of Jerusalem, forming a belt around Jerusalem in the area of the West Bank. Plan no. 1/82 determined five main land-use zones (agriculture, nature reserve, future development, reserved area and built-up village areas). An analysis of the goal containing proposals of land use and regulations, leads to the conclusion that this plan intended to prevent the securing of building permits in agricultural zones according to the Mandate plans, and to limit Palestinian development in villages and in congested built-up areas. However, the areas designated for future development were selected for the creation or expansion of Jewish settlements.

The second plan, issued in 1984, was called the ‘Regional partial outline plan for Roads – Order no. 50’. This plan created a dual road system in the West Bank, the main user of the one being Palestinian, and the other, Jewish. The plan proposed a large set-back (200–300 m) in order to limit Palestinian development…”

— Source: Rassem Khamaisi (1997) Israeli use of the British Mandate planning legacy as a tool for the control of Palestinians in the West Bank, Planning Perspectives, 12:3, 321-340, DOI:10.1080/026654397364672]

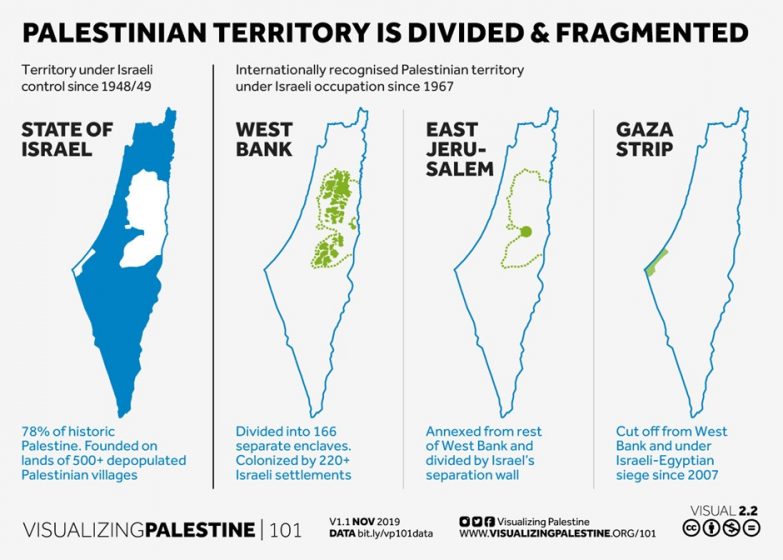

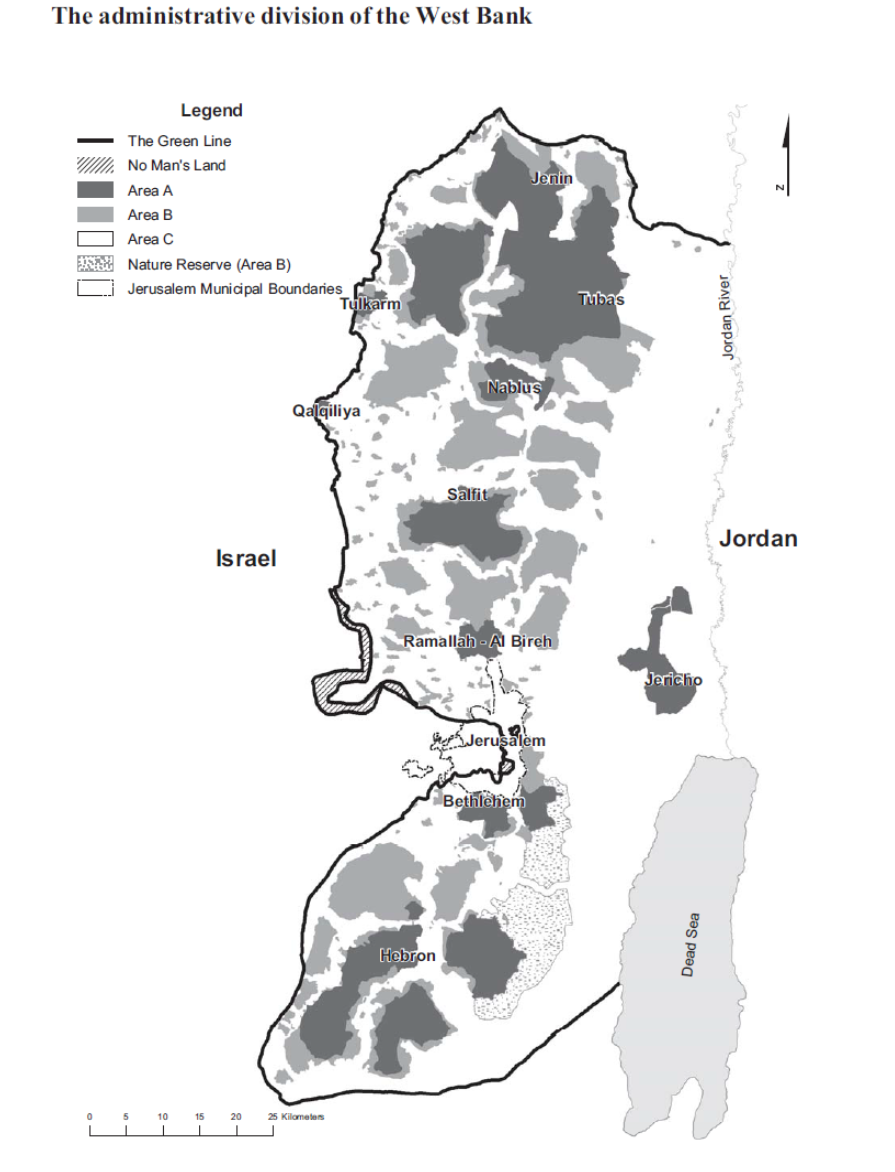

Planning in the West Bank after the Oslo Accords (1995 – today)

The Oslo Peace Accords signed in 1993 were expected to transfer control of the West Bank, including planning powers, to the Palestinians. The reality was markedly different, with the West Bank being divided into three zones (A, B, C). Area A (covering 18% of the West Bank) is administered by the Palestinian Authority and Area B (covering 22% of the West Bank) is under joint Palestinian-Israeli control. Area C, the largest of the zones covering approximately 60% of the area of the West Bank, is under exclusive Israeli administration including planning control. In Area C, planning restrictions on Palestinians have increased compared to the pre-Oslo era, with even less construction permitted. Simultaneously, the expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank continues.

The Israeli NGO Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights describes this juxtaposition of planning powers between Palestinians and the occupying State of Israel in their 2008 report:

“The two sides in this conflict do not have equal power. The Israeli Civil Administration enjoys substantial statutory and legal powers, and the average Palestinian citizen has no practical possibility of successfully challenging its decisions. Even according to the official position of the Israeli government, Area C is under temporary belligerent occupation and is not part of the sovereign State of Israel. This status implies that the powers of the Israeli authorities in the area to impose restrictions on Palestinian development and building are extremely restricted compared to those of a sovereign government. Nevertheless, the Civil Administration severely restricts Palestinian development in Area C, arguing that the future of this area remains to be determined in negotiations for a permanent agreement. At the same time, Israel continues to permit extensive construction in the settlements scattered throughout Area C, as if this construction does not establish facts on the ground and does not have grave ramifications for any future agreement.”

Furthermore, as is typical with the international transfer of planning expertise, British planners brought with them planning solutions which may have worked in Britain but did not necessarily work in Palestine. Crookston elaborates below:

“The echoes of empire ring down to the present in other ways in the Mandate Plans, too… Importing a ‘solution’ intended to tackle the sprawl that was stretching along the radial roads of UK cities, the plans declared wide building-lines to set development well back from primary roads. These are now cited as reasons for demolitions. And the regional plans’ zoning of areas for only a few main uses (roads, an agricultural zone, development zones, nature/forest reserves, and beach reserves) has become a tool for hyper-restriction of natural village expansion.”

In other words, British planning policies which were meant to restrict linear sprawl of town and cities in 20thcentury Britain were imposed on Palestinian villages and are now being used as legal justification for restricting the natural growth of these villages. Critically, the same planning policies were not applied to the Jewish colonies being set up by international Zionist organisations to accommodate hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants, who came mostly from Europe and the United States with no immediate ties to the land of Palestine. Not only were these colonies permitted, but they were also allowed to grow and develop without planning requirements or restrictions.

Rassem Khamaisi, professor at the University of Haifa, describes this dichotomy in applying planning policies as follows in his paper on the British Mandate and the control of Palestinians:” The Arabs were subject to restrictive statutory and physical planning, and land surveys were used as a tool for confiscating their land, particularly in situations of ethnic conflict.

By comparison, new Jewish colonies and towns were rapidly developing to absorb largescale Jewish immigration that came to Palestine, especially after the Second World War. The Mandate planning institutions did not involve approved structure plans for the Jewish agriculture colonies. Besides which, most employees in the Planning Adviser’s office and in the district commissions were Jewish, and some of them paid more attention to the Jewish towns plans than to the implementation of the Mandate policy.”

The Creation of the State of Israel over Palestinian villages (1948 – 1967)

Between 1947 and 1948, to enable the creation of a Jewish state, 750,000 Palestinians were made to flee their homes through violent assaults first by militant Jewish groups and then by the newly formed Israeli state. This moment in history had a significant impact on all aspects of life for Palestinians, including the strength and connectivity of their cities. The quote below is from another work by Khamaisi focusing on the major Palestinian urban centers and how they were affected by the creation of the State of Israel.

“In 1947, the United Nations Assembly partitioned Palestine into two states, Arab and Jewish, under Resolution 181. The War of 1948 between the Arabs and the Jewish, as an aftermath of this resolution, lead (sic) to the establishment of a viable, functional sovereign Jewish state with Tel-Aviv its urban core. This urban core began to develop in the 1930’s even though the Israelis aspired to establish Jerusalem as its Political core after the War of 1948, and according to the Rhodes ceasefire agreement of 1949. The Arab Palestinian state failed to establish, with Palestinian territory outside the Israeli state fragmented into two units lacking territorial continuity. As a result of this war, known as “Nakba” [disaster] to the Palestinians, and territorial fragmentation, the normal growth of Palestinian cities and towns changed in the wake of the establishment of the State of Israel. Israel divided Mandate Palestine under Jordanian rule (West Bank, “WB”) and Egyptian administration (Gaza Strip, “GS”). Between 1948-1967 the Palestinians lost their urban centers in territories within the newly established Israel proper, and the urban centers outside Israel’s borders, ruled by foreign Arab States, remained relatively small and dependent on the Jordanian core and the Egyptian core, Amman and Cairo, respectively. Jerusalem, which had previously functioned as the

Palestinian core, was divided into West Jerusalem, under the sovereignty of the State of Israel, while East Jerusalem was under Jordanian sovereignty and dependent on Amman.” The catastrophic loss of the Nakba was also felt, perhaps even more painfully, in Palestinian villages, hundreds of which were wiped off the map:

“After May 15th 1948 the War expanded and Israeli forces took over portions of the territory that was set aside for the establishment of a Palestinian state through the Partition Plan and expelled much of the population that lived in these areas. By the end of the war approximately 750,000 Palestinians had been made refugees and between 500 and 600 Palestinian villages had been depopulated. Many of these communities were later destroyed.”

— Source: https://www.afsc.org/resource/palestinian-refugees-and-right-return

To cover the traces of these acts of ethnic cleaning, many of the sites of the destroyed villages were later designated by Israeli authorities as nature reserves or cultural sites:

“The razed grounds of 182 erstwhile Palestinian villages — almost half of the villages depopulated by Israel in 1948 — are today included within the boundaries of Israeli nature and recreation spaces: mainly national parks, nature reserves and Jewish National Fund (JNF) forests and parks. Most of the Palestinian villages were intentionally destroyed by Israel during and after the 1948 war or gradually dilapidated due to lack of official care as they were not considered heritage sites worthy of preservation. However, many of the villages were centered on ancient ruins, whose historical value led in some cases to declarations of national parks on the grounds of former villages. Similarly, villages near a natural spring were later classified by Israel as nature reserves or recreation areas; and, lastly, one of the goals behind the planting of some of the JNF forests in Israel — later turned into recreational areas — had been to obscure the remains of destroyed Palestinian villages.”

—Source: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/232332

The multiple layers of colonisation and appropriation involved in such acts of forestation over ruined villages are described piercingly by Liat Berdugo in her essay reflecting on the tree she planted as a child in Jerusalem at the age of six:

“So the planting of forests is a politically charged endeavor that links ecology and aesthetics to cultural survival. It is a way for Israeli Jews to say ‘we are here’… But more than that: it is a strategy for expropriating land. Prior to the declaration of Israeli statehood, the leaders of KKL-JNF [Kayemeth Le’Yisrael, also known as the Jewish National Fund] saw afforestation as ‘a biological declaration of Jewish sovereignty’ that could be used to set up ‘geopolitical facts’.”

She goes on to describe:

“A half-century later, it remains a public secret that at least 46 KKL-JNF forests are located on the ruins of former Palestinian villages. American Independence Park, where the names of foreign donors are etched on the Wall of Eternal Life, is superimposed on the villages of Allar, Dayr al-Hawa, Khirbat al-Tannur, Jarash, Sufla, Bayt ‘Itab, and Dayr Aban, which were captured, ‘depopulated’ of their 4,000 inhabitants, and razed by Israeli state actors in 1948.”

Berdugo also implicates the Israeli legal system which rejects claims of Palestinians to village sites after they have been forested:

“And the Israeli courts have determined that when a forest is grown on expropriated land, Palestinians who return to that land are trespassing. In 2010, the Supreme Court rejected a petition by Palestinian refugees from the village of al-Lajjun to reclaim land in the Megiddo forest, ruling that afforestation justified Israeli control under the Land Acquisition Law of 1953.”

Planning during the military occupation of the West Bank (1967 – 1994)

Planning process in Palestinian centres

In 1967, Israel occupied the remainder of historic Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza). As an occupying power, Israeli authorities now had direct control over planning laws in these areas.

Rassem Khamaisi describes how the Israeli state took away agency and representation in planning from the indigenous Palestinian population through the issuance and implementation of Military Order (MO) 148 which transferred planning powers from local village councils to commissions appointed by the Israeli military:

“The MO no. 418 also abolished the local planning commission in village councils, later establishing six Regional Rural Planning Committees (RRPC). It also granted the Military Commander the authority to appoint members of the HPC [Higher Planning Commission] and RRPC. Under the MO, the HPC was also authorized to set up subsidiary or ad hoc committees as it deemed necessary. Once the MO had been issued and implemented, the Palestinians were robbed of all authority and responsibility in the planning institutions; their presence in the province and RRPC, or in the sub-commission of the HPC, was merely formal. The ‘responsible’ in charge set up the HPC and appointed Jewish members with no Palestinian representation.”

In this new planning system, most Palestinian applications for detailed plans or building permits were rejected on the pretence of protecting agricultural land or lack of sufficient land ownership documentation. This is captured in numbers by Khamaisi:

“Thus, obtaining a building permit was a very complicated and serious process, which decreased the number of building permits issued to the Palestinians. For example, in the period between 1 January 1988–1 September 1988, the number of applications submitted was 994, but the number of permits given was only 221. It is worth mentioning that in the period between 15 November 1986 and 28 September 1987 no permits at all were issued by the local committees.”

Establishment of new Jewish settlements

The HPC prepared regional plans for the West Bank in the early 1980s with multiple colonial objectives including limiting the development of Palestinian villages, severing connectivity of Palestinian cities, and most importantly enabling the establishment of Israeli settlements in the West Bank with full spatial segregation from Palestinians. In Khamaisi’s words:

“To amend the Mandate plans in the regional tier, the HPC prepared two regional plans covering part of the West Bank. The first, called the ‘Partial regional plan no. 1/82, amendment to regional plan RJ-5’, emerged in 1982. This plan covered an area of about 45 km2, around the three sides of Jerusalem, forming a belt around Jerusalem in the area of the West Bank. Plan no. 1/82 determined five main land-use zones (agriculture, nature reserve, future development, reserved area and built-up village areas). An analysis of the goal containing proposals of land use and regulations, leads to the conclusion that this plan intended to prevent the securing of building permits in agricultural zones according to the Mandate plans, and to limit Palestinian development in villages and in congested built-up areas. However, the areas designated for future development were selected for the creation or expansion of Jewish settlements.

The second plan, issued in 1984, was called the ‘Regional partial outline plan for Roads – Order no. 50’. This plan created a dual road system in the West Bank, the main user of the one being Palestinian, and the other, Jewish. The plan proposed a large set-back (200–300 m) in order to limit Palestinian development…”

— Source: Rassem Khamaisi (1997) Israeli use of the British Mandate planning legacy as a tool for the control of Palestinians in the West Bank, Planning Perspectives, 12:3, 321-340, DOI:10.1080/026654397364672]

Planning in the West Bank after the Oslo Accords (1995 – today)

The Oslo Peace Accords signed in 1993 were expected to transfer control of the West Bank, including planning powers, to the Palestinians. The reality was markedly different, with the West Bank being divided into three zones (A, B, C). Area A (covering 18% of the West Bank) is administered by the Palestinian Authority and Area B (covering 22% of the West Bank) is under joint Palestinian-Israeli control. Area C, the largest of the zones covering approximately 60% of the area of the West Bank, is under exclusive Israeli administration including planning control. In Area C, planning restrictions on Palestinians have increased compared to the pre-Oslo era, with even less construction permitted. Simultaneously, the expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank continues.

The Israeli NGO Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights describes this juxtaposition of planning powers between Palestinians and the occupying State of Israel in their 2008 report:

“The two sides in this conflict do not have equal power. The Israeli Civil Administration enjoys substantial statutory and legal powers, and the average Palestinian citizen has no practical possibility of successfully challenging its decisions. Even according to the official position of the Israeli government, Area C is under temporary belligerent occupation and is not part of the sovereign State of Israel. This status implies that the powers of the Israeli authorities in the area to impose restrictions on Palestinian development and building are extremely restricted compared to those of a sovereign government. Nevertheless, the Civil Administration severely restricts Palestinian development in Area C, arguing that the future of this area remains to be determined in negotiations for a permanent agreement. At the same time, Israel continues to permit extensive construction in the settlements scattered throughout Area C, as if this construction does not establish facts on the ground and does not have grave ramifications for any future agreement.”

Source: The Prohibited Zone: Israeli planning policy in Palestinian Villages in Area C, Bimkom, June 2008

Jerusalem

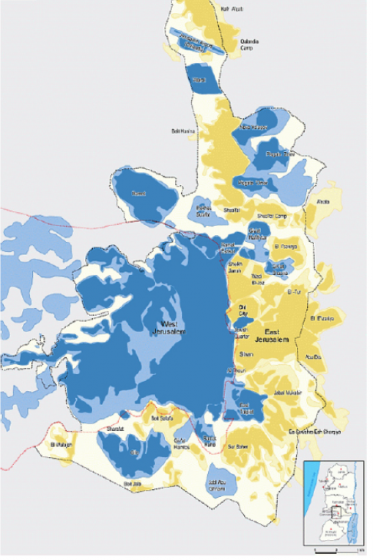

The Israeli planning interventions in the city of Jerusalem, particularly after the 1967 war, offer a rich albeit disheartening case study of planning as a tool for segregation. Some of the injustices have risen to the world scene earlier this year as Palestinian families in neighbourhoods such as Sheikh Jarrah fight illegal dispossession from their homes. Jonathan Rock Rokem has written extensively on this topic, terming Jerusalem as a “Contested City”. Below are excerpts from a 2012 paper on the politics of urban planning in the city:

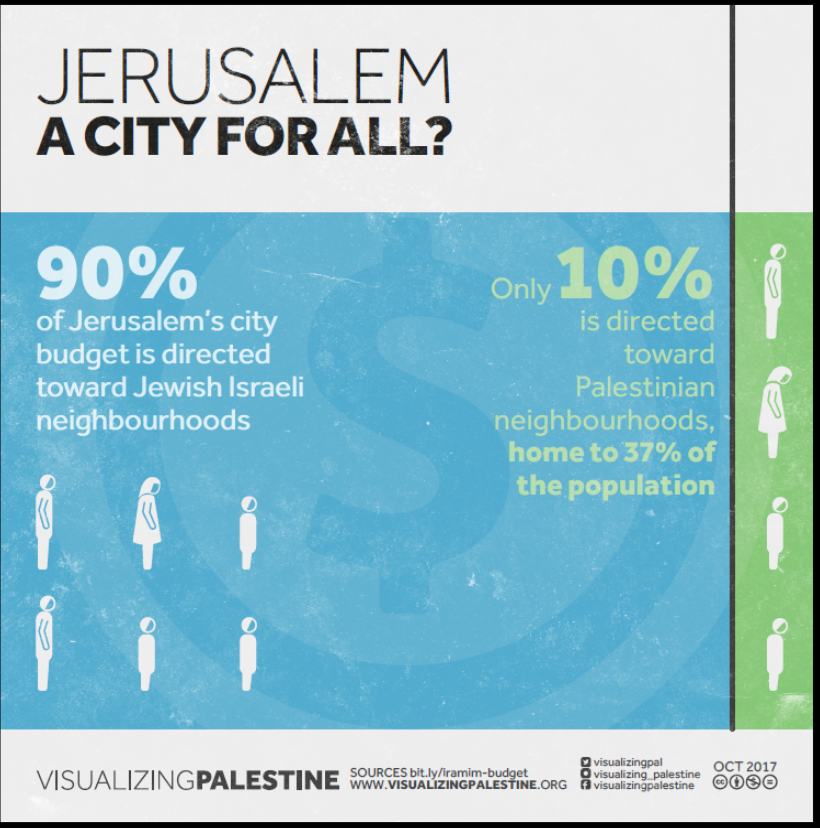

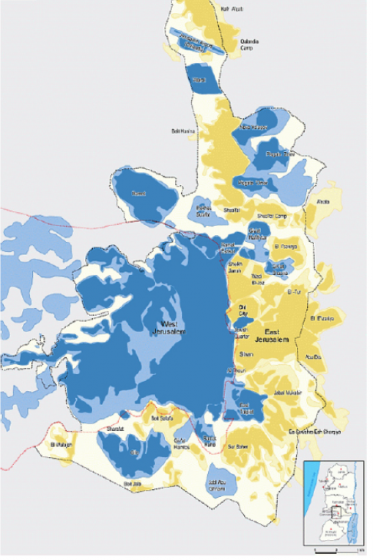

“Israel, with the Ministry of Interior and the Jerusalem Municipality as its main legislative arms, has been responsible for urban planning and policy for the last 45 years, keeping a clear separation between Israeli and Palestinian living areas clearly visible in the location of disconnected living areas in the map below, dating from 2008.”

“In more details, over the last 46 years, Israel has used its military might and economic power to relocate borders and form boundaries, grant and deny rights and resources, shift populations, and reshape the Occupied Territories for the purpose of ensuring Jewish control. In the case of East Jerusalem, two complementary strategies have been implemented by Israel: the construction of a massive outer ring of Jewish neighborhoods which now host over half the Jewish population of Jerusalem, and the containment of all Palestinian development, implemented through housing demolitions, legally banning Palestinian construction and development, and the prevention of Palestinian immigration to the city.”

“Up until today, planning and development in Jerusalem has been officially determined by the last statutory authorized master plan dating from 1959. The 1959 “[The] Scheme, prepared at the time when Jerusalem was a divided city, includes only the Western part of the pre-1967 Israeli Jerusalem. Therefore, it has little relevance in determining planning and development in the current conditions. This means that without an updated master plan, for almost 50 years, the Municipality, the Ministry of Interior, and other government departments have shared the development and planning without an overall legally binding document.”

“Since 1967, the policy employed by the Jerusalem municipality has been affected by the Israeli national political discourse. The principal Israeli policy has been “reunifying” Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty while the Palestinian Eastern population sees the integration of East Jerusalem as illegal “annexation.” In ethnically divided cities, urban planning policy can take a major role in enhancing spatial and social division (Bollens 2000). The unequal funding of urban planning and construction projects between the Eastern and the Western parts has resulted in a city split into two distinct growth poles, with the crossover parts and old border areas remaining mainly neglected division points between the two sides.”

Jerusalem

The Israeli planning interventions in the city of Jerusalem, particularly after the 1967 war, offer a rich albeit disheartening case study of planning as a tool for segregation. Some of the injustices have risen to the world scene earlier this year as Palestinian families in neighbourhoods such as Sheikh Jarrah fight illegal dispossession from their homes. Jonathan Rock Rokem has written extensively on this topic, terming Jerusalem as a “Contested City”. Below are excerpts from a 2012 paper on the politics of urban planning in the city:

“Israel, with the Ministry of Interior and the Jerusalem Municipality as its main legislative arms, has been responsible for urban planning and policy for the last 45 years, keeping a clear separation between Israeli and Palestinian living areas clearly visible in the location of disconnected living areas in the map below, dating from 2008.”

“In more details, over the last 46 years, Israel has used its military might and economic power to relocate borders and form boundaries, grant and deny rights and resources, shift populations, and reshape the Occupied Territories for the purpose of ensuring Jewish control. In the case of East Jerusalem, two complementary strategies have been implemented by Israel: the construction of a massive outer ring of Jewish neighborhoods which now host over half the Jewish population of Jerusalem, and the containment of all Palestinian development, implemented through housing demolitions, legally banning Palestinian construction and development, and the prevention of Palestinian immigration to the city.”

“Up until today, planning and development in Jerusalem has been officially determined by the last statutory authorized master plan dating from 1959. The 1959 “[The] Scheme, prepared at the time when Jerusalem was a divided city, includes only the Western part of the pre-1967 Israeli Jerusalem. Therefore, it has little relevance in determining planning and development in the current conditions. This means that without an updated master plan, for almost 50 years, the Municipality, the Ministry of Interior, and other government departments have shared the development and planning without an overall legally binding document.”

“Since 1967, the policy employed by the Jerusalem municipality has been affected by the Israeli national political discourse. The principal Israeli policy has been “reunifying” Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty while the Palestinian Eastern population sees the integration of East Jerusalem as illegal “annexation.” In ethnically divided cities, urban planning policy can take a major role in enhancing spatial and social division (Bollens 2000). The unequal funding of urban planning and construction projects between the Eastern and the Western parts has resulted in a city split into two distinct growth poles, with the crossover parts and old border areas remaining mainly neglected division points between the two sides.”

Source: Rock, J; (2012) Politics and Conflict in a Contested City: Urban Planning in Jerusalem under Israeli Rule. Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem, 23

What now?

Around the world, urban planning is inextricably linked to both historic and current power structures. Urban planning in Palestine over the past century is no exception. Perhaps what differentiates Palestine today is the ongoing settler colonialization. Unlike other settler colonialization “projects” (e.g., in the US and Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and South Africa), the Israeli colonial regime is still formally in power today and continues to perpetrate injustices at every scale against the occupied Palestinian population. As I have attempted to argue in this essay, spatial planning policy has been an important tool in creating today’s inhumane reality affecting millions of Palestinians on the ground and in the diaspora.

Where do we go from here? The first objective is obvious: ending the colonial project in Palestine. After that point, there will be decades of injustices and abuses to rectify, including the legacy challenges of the planning system, in order to plan for just and liveable cities for all people on that land.

Until then, as built environment professionals, it is important that we denounce the fundamentally unjust systems governing the urban context in Palestine and elsewhere, and continue to work towards rectifying this. For professionals interested in working in Palestine, being fully aware of the colonial planning power dynamics and their impacts is essential to making informed decisions on the projects in which we chose to be involved and the stakeholders and communities we chose to include.

Huda Shaka

Jeddah

On The Nature of Cities

What now?

Around the world, urban planning is inextricably linked to both historic and current power structures. Urban planning in Palestine over the past century is no exception. Perhaps what differentiates Palestine today is the ongoing settler colonialization. Unlike other settler colonialization “projects” (e.g., in the US and Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and South Africa), the Israeli colonial regime is still formally in power today and continues to perpetrate injustices at every scale against the occupied Palestinian population. As I have attempted to argue in this essay, spatial planning policy has been an important tool in creating today’s inhumane reality affecting millions of Palestinians on the ground and in the diaspora.

Where do we go from here? The first objective is obvious: ending the colonial project in Palestine. After that point, there will be decades of injustices and abuses to rectify, including the legacy challenges of the planning system, in order to plan for just and liveable cities for all people on that land.

Until then, as built environment professionals, it is important that we denounce the fundamentally unjust systems governing the urban context in Palestine and elsewhere, and continue to work towards rectifying this. For professionals interested in working in Palestine, being fully aware of the colonial planning power dynamics and their impacts is essential to making informed decisions on the projects in which we chose to be involved and the stakeholders and communities we chose to include.

Huda Shaka

Jeddah

On The Nature of Cities

No comments:

Post a Comment