the good oil (SIC) in green transition

The region that has long dominated global energy

politics is well placed to shape a shift to new supplies.

Attempts to rapidly scale up hydrogen production speaks to the desire by GCC states to be early movers in the sector, supplying both European and Asian markets

politics is well placed to shape a shift to new supplies.

Attempts to rapidly scale up hydrogen production speaks to the desire by GCC states to be early movers in the sector, supplying both European and Asian markets

(Maya Siddiqui/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

ACHREF CHIBANI

Published 4 Jul 2023 Energy

Hydrogen has been hailed as an energy of the future and the technical fix in the green transition. But as hydrogen’s technological and cost barriers continue to fall, there remain political barriers to hydrogen as a green energy technology in the 21st century. This is just as true for the Gulf states, who have been traditional geographic powerhouses in the oil economy. The policies, legislation, production and infrastructure adopted by the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) states will be crucial to shaping the role of hydrogen in the years ahead.

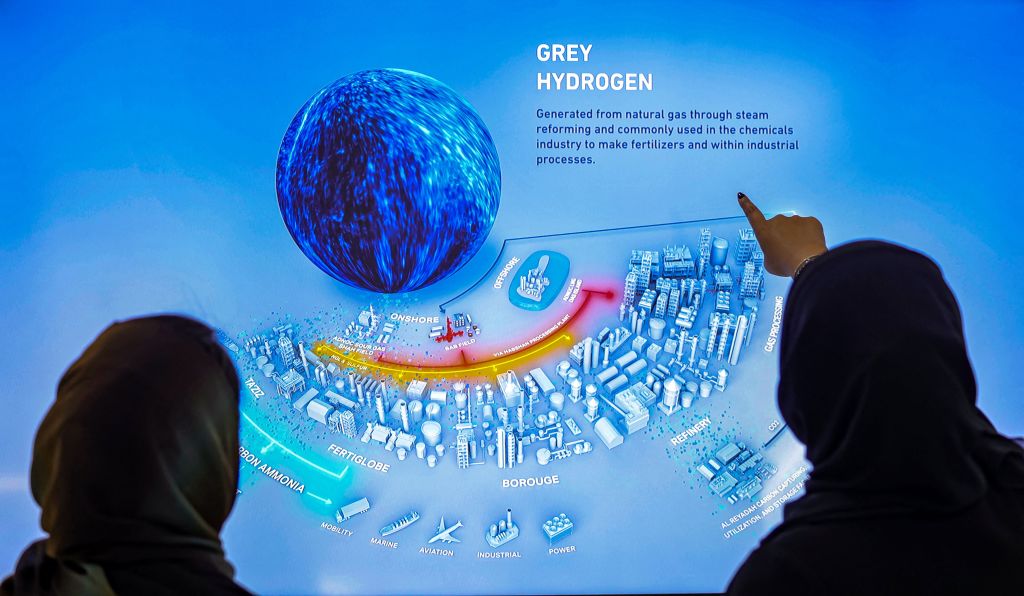

This is because hydrogen represents an energy carrier and store rather than source, i.e., it requires other energy for its manufacture. The green credentials of hydrogen are therefore highly dependent on what energy inputs are included in its production. Colours are used to distinguish between different energy sources, so while “green hydrogen” is produced solely from renewable energy sources such as wind, solar and hydro, “grey hydrogen” employs natural gas, and “blue hydrogen” is produced from natural gas or coal but can incorporate carbon capture and storage into the production process.

The GCC states are well suited to the production of green, grey and blue hydrogen and eye-catching reports have predicted that those states may generate annual revenues of as much as US$200 billion from green hydrogen by 2050. The region’s hydrogen policy began in 2019 when Oman, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait started to outline hydrogen strategies and publicise ambitious hydrogen projects. Most notably, Saudi Arabia announced plans to produce 1.2 million tonnes of green-hydrogen-based ammonia as part of its NEOM megaproject. The project, which is a joint venture between the state-owned NEOM, Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power and the US company Air Products, is estimated to cost US$8.4 billion and to come online in 2026.

An infographic about grey hydrogen, produced from natural gas, on display at the UAE pavilion during the COP27 climate conference last year in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt

(Fayez Nureldine/AFP via Getty Images)

Attempts to rapidly scale up hydrogen production speak to the desire by GCC states to be early movers in the sector and position the region as a global hub for hydrogen, supplying both European and Asian markets. The region has several competitive advantages including the relative low cost of land across Gulf states, high potential solar power generation, existing industrial capacity and underground storage options for carbon sequestration in the production of blue hydrogen.

If, in the 20th century, Gulf states were reliant on Europe and the United States to help develop their oil resources, the hydrogen economy is likely to reflect shifts in global power. GCC states are aware of the potential to become market leaders in hydrogen technologies, which would offer the added benefit of being able to sell hydrogen manufacturing, storage and transportation technologies and expertise to the rest of the world. Just as American oil engineers and companies made their fortunes in the Gulf in the mid-20th century, it is not inconceivable that Arab hydrogen expertise might be exported to the world in the 21st century.

A tanker-based hydrogen transportation regime may well benefit GCC states, allowing them to convert their current port infrastructure to mirror current hydrocarbon shipping lanes.

Though Europe has looked to nurture hydrogen energy relations with the GCC, the Asia-Pacific is emerging as the most attractive hydrogen market for Gulf states who have begun to actively look to build relations with Asian partners. Saudi Arabia has signed memorandums of understanding on hydrogen with China and Japan’s Marubeni Corporation. Oman, meanwhile, has entered into an agreement with a consortium of South Korean companies to build and operate hydrogen plants in the Sultanate. It is likely that this kind of “hydrogen diplomacy” will grow in importance as new markets are developed. In addition, there are signs of growing competition between rival hydrogen-producing states. Outside the Gulf, Egypt and Morocco are also vying to be regional leaders in hydrogen production.

Key to securing the region’s hub status will be its ability to develop hydrogen infrastructure that can transport energy to markets. Reflecting Gulf states’ preference for bilateral energy relations, states have historically forgone pipelines in preference for tankers as the means to transport hydrocarbons to their consumers. While hydrogen pipelines have been proved effective over short to medium distances, it is expected that hydrogen will be transported by tanker over longer distances.

A tanker-based hydrogen transportation regime may well benefit GCC states, allowing them to convert their current port infrastructure to service hydrogen transportation and for a global hydrogen network to mirror current hydrocarbon shipping lanes. Admittedly, this would reproduce current energy transportation security concerns and chokepoints – such as the Strait of Hormuz or the Malacca Strait – but it is likely that global maritime and energy corporations will favour known risks over navigating a new energy geography and its attendant security regime.

As GCC states engage with the energy transition, it is unsurprising that new hydrogen technologies are proving an attractive alternative to hydrocarbons. In many ways, they allow GCC states to maintain the global energy status quo, retaining the Gulf’s position as the paramount energy producer and exporter. That said, hydrogen is not oil, and it is likely to produce new geopolitical dynamics that reshape international politics.

Attempts to rapidly scale up hydrogen production speak to the desire by GCC states to be early movers in the sector and position the region as a global hub for hydrogen, supplying both European and Asian markets. The region has several competitive advantages including the relative low cost of land across Gulf states, high potential solar power generation, existing industrial capacity and underground storage options for carbon sequestration in the production of blue hydrogen.

If, in the 20th century, Gulf states were reliant on Europe and the United States to help develop their oil resources, the hydrogen economy is likely to reflect shifts in global power. GCC states are aware of the potential to become market leaders in hydrogen technologies, which would offer the added benefit of being able to sell hydrogen manufacturing, storage and transportation technologies and expertise to the rest of the world. Just as American oil engineers and companies made their fortunes in the Gulf in the mid-20th century, it is not inconceivable that Arab hydrogen expertise might be exported to the world in the 21st century.

A tanker-based hydrogen transportation regime may well benefit GCC states, allowing them to convert their current port infrastructure to mirror current hydrocarbon shipping lanes.

Though Europe has looked to nurture hydrogen energy relations with the GCC, the Asia-Pacific is emerging as the most attractive hydrogen market for Gulf states who have begun to actively look to build relations with Asian partners. Saudi Arabia has signed memorandums of understanding on hydrogen with China and Japan’s Marubeni Corporation. Oman, meanwhile, has entered into an agreement with a consortium of South Korean companies to build and operate hydrogen plants in the Sultanate. It is likely that this kind of “hydrogen diplomacy” will grow in importance as new markets are developed. In addition, there are signs of growing competition between rival hydrogen-producing states. Outside the Gulf, Egypt and Morocco are also vying to be regional leaders in hydrogen production.

Key to securing the region’s hub status will be its ability to develop hydrogen infrastructure that can transport energy to markets. Reflecting Gulf states’ preference for bilateral energy relations, states have historically forgone pipelines in preference for tankers as the means to transport hydrocarbons to their consumers. While hydrogen pipelines have been proved effective over short to medium distances, it is expected that hydrogen will be transported by tanker over longer distances.

A tanker-based hydrogen transportation regime may well benefit GCC states, allowing them to convert their current port infrastructure to service hydrogen transportation and for a global hydrogen network to mirror current hydrocarbon shipping lanes. Admittedly, this would reproduce current energy transportation security concerns and chokepoints – such as the Strait of Hormuz or the Malacca Strait – but it is likely that global maritime and energy corporations will favour known risks over navigating a new energy geography and its attendant security regime.

As GCC states engage with the energy transition, it is unsurprising that new hydrogen technologies are proving an attractive alternative to hydrocarbons. In many ways, they allow GCC states to maintain the global energy status quo, retaining the Gulf’s position as the paramount energy producer and exporter. That said, hydrogen is not oil, and it is likely to produce new geopolitical dynamics that reshape international politics.

No comments:

Post a Comment