DSA, the Democratic Party and the radicalization process

“DSA, the Democratic Party, and the Radicalization Process,” by Paul Le Blanc, is a follow-up piece to “Beyond ‘No Kings’”, a conversation between Le Blanc and John Meehan, and to “Lessons from the DSA Convention”, published on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal and Communis on 14 July 2025 (revised and in expanded form) and 15 August 2025, respectively. This follow-up is appearing simultaneously on LINKS and Communis.

***

Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is neither static nor stable. It has been going through membership fluctuations, including a current growth spurt, and it has been radicalizing. From its very beginning it has had close ties with the Democratic Party. But as former party leader Nancy Pelosi explained several years ago to DSA Congressperson Alexandria Ocasio Cortez (AOC), who — with a growing number of other DSAers had used the Democratic ballot-line to get elected to office —, the Democratic Party is an unequivocally capitalist party. How do we work our way through the resulting complexity and contradiction? On her own, AOC has chosen a certain balance that blends her eloquent idealism with quite significant compromises. Some members find the result unacceptable — but DSA has yet to resolve the dilemma.

No serious revolutionary would be satisfied with memorizing a list of formulas and slogans that one can simply repeat over and over and over, regardless of what is actually happening in the world. But saying this resolves nothing. It is a truth that can be agreed to by those who, nonetheless, end up doing precisely that. It can also be agreed to by those who, for all practical purposes, tacitly abandon a revolutionary outlook for the purpose of adapting to something that seems more practical and realistic.

Failing to transcend either sectarian or opportunist traps can prevent the creation of an effective democratic socialist movement capable of overcoming the horrors and dangers of our time. The possibilities of failure are undeniable and incredibly imposing. Yet many continue to seek humanistic, democratic, revolutionary pathways to a better future. In the United States at this moment, there is an incipient, growing spread of protests and insurgencies pushing in that direction. But there seem to be no clear answers on how, truly, to bring such a transformation. Because human beings are complex creatures immersed in diverse and complex situations, and without telepathic powers, it is not a simple thing to develop those clear answers. To accomplish that, we need a collective process of discussion and deliberation, with organizations of activists to develop and communicate proposals that people can consider and respond to.

There are a number of fairly tiny socialist organizations in our country, some more best equipped than others, that have proved unable to function effectively or consistently on a large scale. One organization, by far the largest socialist formation in the United States, does seem however to have a possibility of playing a significant role in the political mainstream, and it is precisely Democratic Socialists of America. It currently boasts a membership of more than 80,000 and some predict it will soon top 100,000. It is estimated that only about 10 percent of these are active — although the size of this activist core still is significantly larger than other left-wing groups. It is essential for committed revolutionaries not simply to be satisfied with superficial characterizations of DSA, but rather to comprehend the actual significance of this organization.1

I. Growth and radicalization

DSA has grown from a few thousand on the fringe of liberal politics to many thousands who have already played a role in the political mainstream, and who seem poised to make socialism a force to be reckoned with on the political scene. If the organization had a single, identifiable architect, that person was obviously Michael Harrington — a highly articulate writer, speaker, and organizer.2 Harrington honed a somewhat appealing but remarkably moderate orientation which he tagged “democratic Marxism.” In terms of practical politics — to which he was passionately committed — this orientation involved what some have termed the realignment strategy.

The realignment strategy had developed within the predominant circles of the DSA predecessor, the Socialist Party of America, in the 1960s. It envisioned the evils of capitalism being gradually whittled away by a steady accumulation of reforms. This would be advanced by a coalition whose central elements would be the labor movement, the civil rights movement, and the multi-faceted liberal community. In a 1976 debate, Harrington argued that this coalition could and should, ultimately, become the defining element in the Democratic Party:

The Democratic Party is a mish-mash, everybody knows it. I belong to the liberal, trade union, anti-war, Black, feminist, reformist wing of the Democratic Party, where I wear “socialism” on my sweatshirt in very red letters.3

The other essential element in the realignment strategy involved working patiently and consistently in the Democratic Party as a precondition for shifting its platform and policies to the left — voting for Democratic Party liberals and centrists “as the first stage in trying to make the transformation which this society so desperately needs.”4

Gradually, conservatives, racists, and reactionaries — according to the realignment analysis developed by Max Shachtman, Bayard Rustin, Tom Kahn, Michael Harrington and others — would migrate to the Republican Party, while the Democrats became consolidated as an anti-racist and economic justice party of the working-class majority, for all practical purposes functioning along the lines of the social-democratic parties of Sweden’s Olof Palme and West Germany’s Willy Brandt.5

According to Doug Greene’s 2021 account, Harrington’s approach remained dominant within the organization he helped to found in 1982. “If Michael Harrington returned from the dead and saw DSA today, he would largely feel vindicated,” Greene tells us. “Harrington would believe that DSA’s growth in membership was largely the result of pursuing Realignment.”6

This judgement is at sharp variance, however, with the perceptions of three aging radicals who strongly identified with Harrington’s DSA at least until the mid-1990s.

After the death of Harrington in 1989 (and of his ally Dissent editor Irving Howe in 1993), in the opinion of Paul Berman (himself a Dissent editorial board member, who seems dissatisfied with the current evolution of Dissent), DSA simply found itself “adrift,” although it has been “capable lately of attracting young people out of a nostalgia for the class struggles of yore.” However — cautions Berman — it is “no longer capable of generating a major leader.”

In 2020, Jo-Ann Mort — a close comrade of Harrington’s in the 1970s and ’80s — observed, in contrast, that “DSA is thriving, no doubt about it, with some 60,000 members as opposed to the few thousand back in Mike’s day,” but she went on to emphasize: “I suspect that Harrington would find himself, were he alive, disowning the organization he founded — and its leadership would most likely disown him, too.” The primary issue, in her opinion, would have been DSA’s new “inexplicable purity” and “sectarianism” compared with Harrington’s unflinching commitment to the Democratic Party. She approvingly quotes him: “We see the growth of a mass socialist movement growing out of liberalism very broadly defined, a movement of radical change growing out of a movement of partial change.

Maurice Isserman explained his own decision to leave DSA a few years later. He also noted the influx of new and younger members. “Unknown numbers — hundreds, perhaps more — started joining in 2016,” he wrote. Some of them have a “Marxist-Leninist” orientation and (in his judgment) pernicious intentions. Despite differences among these newcomers to DSA, they have a common aim: “to take a well-meaning, not particularly well-organized, and essentially social democratic organization still committed in practice to the original DSA vision of creating ‘the left wing of the possible,’ and reinvent it as the mass vanguard party of the proletariat …”

Berman, Isserman, and (to a lesser extent) Mort also touch on what is for them an additional factor causing these three to reject DSA: the organization’s growing hostility toward Israel as a Jewish state. As Berman frankly notes, Harrington could be counted on to be “sympathetic to the Zionist cause,” and this inclination was predominant within the old DSA. One aspect of DSA’s current radicalization is the fact that this is no longer the case. A majority of DSA members share positions articulated by Rashida Tlaib and Zohran Mamdani (charismatic leaders, despite Berman’s prediction that the new DSA would be incapable of generating them).

In the 2025 New York Mayoral primary debate Mamdani openly diverged from the other candidates on this matter. “I believe Israel has the right to exist,” he said, “as a state with equal rights.” Unlike the other candidates, he did not support Israel as a Jewish state (in which Jews, before all others, have full rights). This exclusionary element is part of the meaning of Zionism. Israel as a Zionist project, as a Jewish state, has increasingly meant that non-Jews (especially Palestinians) are not fully accepted or are persecuted, including through policies of ethnic cleansing. Over the past year, such Zionist policies — it is very widely understood in the world — have morphed into outright genocide.

Harrington’s realignment orientation and his Zionist sympathies largely relied on a particular analysis of imperialism. This analysis contrasted with that developed by such Marxist theorists of the early 20th century as Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg. They understood imperialism as an economic expansionism, exploitative and oppressive, that was generated by a voracious capital accumulation process. This process of capital accumulation was essential to the nature and functioning of the capitalist economy. It naturally and necessarily resulted in the economic expansionism of imperialism and was, in turn, accompanied by militarism and war. Lenin’s and Luxemburg’s analysis undermined two key aspects of Harrington’s orientation.

First, if capitalism was naturally and necessarily imperialist, a gradualist and reformist approach would be problematic — continually distorted and undermined by the foreign policy requirements of corporate-capitalism’s imperial order. Only a revolutionary change, ushering in a different economic system, could be consistent with the gradual and ongoing improvements that Harrington sought. And any political party, if dominated by those who were dedicated to meeting such corporate-imperial requirements, would be a dubious framework within which someone genuinely democratic and genuinely socialist could be expected to function.

Secondly, to the extent that Zionism is aligned with the imperialist powers (certainly true of Theodor Herzel, Zionism’s founding icon and leading light), it is inseparable from a brutal exploitation of resources and oppression of the peoples of the oil-rich Middle East.

Harrington drew on the views of Karl Kautsky, a formerly revolutionary theorist among the Marxists who had adapted to the bureaucratic (decidedly non-revolutionary) leadership of the German Social Democratic Party shortly before the First World War. Kautsky argued that imperialism was not a necessity for capitalism, but instead a nasty policy option that could be rejected. This added up to what Harrington tagged an “almost-imperialism” — which meant that those supporting democracy and socialism, and had a gradual and reformist orientation, could realistically work to achieve better, non-violent, non-exploitative, non-oppressive policies. For Harrington, this meant that revolution was not a necessary pathway, and that more liberal and humane forms of capitalism and Zionism could be successfully fought for and won, on the road to securing a better, increasingly socialist world.7

Much of the Harrington tradition has melted away in the face of what is happening today. We see a Democratic Party establishment pathetically incapable of leading a consistent and effective resistance to the Trump regime’s vicious policies that transfer ever greater wealth to profiteering billionaires at the expense of the working-class majority. Both political parties continue to enable ongoing mass murder in Gaza, funding and equipping the criminal regime that is doing the killing. The resulting radicalization among the younger activists flooding into DSA is matched by a deepening militancy among those who have been in the organization for a while.

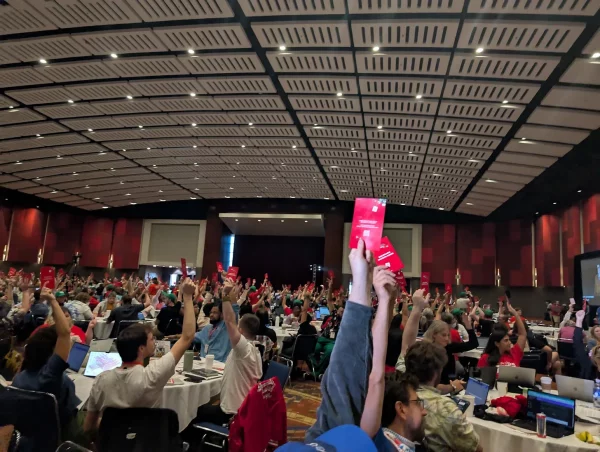

At the 2025 National Convention of DSA that I recently attended, a vibrant radicalism was quite evident among the mostly young delegates. One could see a general disgust and anger towards the Democratic Party, which seemed incapable of mobilizing an effective resistance to an increasingly grotesque Trumpism. One could see as well as widespread horror and indignation over the policies of the Israeli regime — acquiesced to by both Democratic and Republican party establishments — that were resulting in the ongoing and systematic slaughter of tens of thousands of innocent men, women, and children in Gaza. Michael Harrington’s old upbeat formulas from a bygone era had been left far behind. Significant convention majorities embraced resolutions crafted and advanced by the left-wing caucuses on electoral policy and Zionism.

Regarding elections, sentiment has shifted against simply providing DSA endorsement to Democrats or other candidates who seem to qualify as liberals or “progressives,” even those sporting socialist sympathies. There is a decided preference for running those considered to be DSA cadres — those who will campaign as open socialists and who are committed to advancing the program of the organization and to working with their comrades to help make that so, as an integral part of what they will be doing if elected.

The thrust of the resolutions adopted reflects this radicalization — insisting that any candidate DSA endorses must be an open socialist, making this part of their campaign. There is also now a stated intention to begin a serious exploration of possibilities for running a socialist candidate for President in 2028. Also, all candidates and elected officials supported by DSA must be committed to consistently opposing Zionism and Israeli policy in Palestine — and the same goes for DSA spokespeople and members.

One must recognize, however, that within the language of the radical resolutions, there are ambiguities and compromise formulas. How to interpret and negotiate such ambiguities will be largely determined between conventions by the National Political Committee, in which the moderate caucuses continue to hold a sizeable — yet diminishing — number of positions. It is a distinct minority, even more so coming out of the 2025 convention. Yet across the caucus spectrum there is a disinclination to weaken the organization through expulsions and splits, or to run roughshod over the sensibilities of the membership. Within the caucuses themselves, it should be added, there is often significant diversity. Also, while the caucuses have become an organic part of how DSA functions, an overwhelming majority of DSA members remain outside of any caucus.

This relates to the additional fact in some ways more decisive than national decisions — what happens on the ground in DSA locals around the country. There are no centralized structures or disciplined norms to overcome the reality of relatively de-centralized functioning. As Maurice Isserman put it, DSA is “not particularly well-organized,” nor are its members inclined to do things that don’t make sense to them.

II. Rashida Tlaib’s keynote address

If one wants to understand the thinking of a majority of DSA members — with a breadth that includes many in both the moderate wing and the left-wing of the organization — one should consider the comments in Rashida Tlaib’s keynote address, which drew an incredibly enthusiastic response and ovation from the convention as a whole. The entire address is worth listening to and is available online via YouTube. Here are some of the significant portions.

Comrades, we know that this is the moment for our movement …

Before I begin, I want to ground myself in my roots. Not only as the daughter of Palestinian immigrant parents, but as a girl that was raised in the most beautiful, blackest city, in a southeast Detroit neighborhood where you find 20 different beautiful ethnicities, where movements are birthed. It’s where each neighborhood has a history that was rooted in the streets, not City Hall. Movements that grew from the ground up, not legislative branches full of sellouts and corporate boardrooms.

Detroit, my siblings, has firsthand seen the pain and hurts of policies rooted in racism and capitalistic schemes that keep our families in survivor mode. If there is any city that can take down fascism, it is my birth city … Transformative change in our country always comes from us, not the White House and not the United States Congress. Both of these didn’t care about the right to organize unions or passing the Civil Rights Act or the Voting Rights Act, until people pushed them from the outside in …

We have watched in horror for years as both the Democrats and Republicans have ignored the working class to carry out wars to help the 1% and the billionaires. And now a genocide of the Palestinian people … They would rather send bombs and money to a rogue, violent, apartheid state than fund free health care here at home. Both party establishments should forever be condemned by their immoral participation in one of history’s worst crimes, at the expense of the American people …

DSA has always been rooted in the growing anti-war movement in our country, one that is centered on dismantling capitalistic systems that benefit from death, exploitation, oppression, and pain … DSA knows that when we say, “free Palestine,” we are also saying water is a human right, health care for all, fuck wars, end mass incarceration, abolish ICE, housing for all, and so much more … The system and structures around us kill our people, our neighbors …

Our government is scared of our movement, and they’re increasingly desperate (y’all, I watch them!), desperate. Repression shows how weak they really are in the face of our people … It’s past time that my colleagues [should] stop making excuses, trying to strategize and think that somehow there’s a strategy around genocide … There will be a reckoning for these monstrous crimes, and the excuses of war criminals and those genocidal funders and cheerleaders will not save them from the justice that they will see in their communities …

There is revolutionary energy in the air. It’s the first time that I’ve ever felt there’s an alliance of people that are anti-war but they’re also anti-billionaire class, pushing back and saying, “tax the fucking rich!” It’s our duty, DSA, to cultivate this people’s power into a force that can fight fascism and win. A united front is needed in order to beat back savagery … When you caucus, when you come together, understand this is our duty, this is our responsibility, this is our moment.

You don’t need to tell me that the Democratic Party establishment has completely failed to present meaningful resistance to this billionaire class, to Trump and fascism. Their donors are the same. At the end of the day, they serve the same interests — Capital and Empire …

But that’s why DSA is so important. We’re able to honestly, truly, authentically diagnose the problems facing working-class Americans and fight for real change that addresses these problems at the root. The working masses, y’all, they’re hungry for revolutionary change. And DSA can grow as a political force when it focuses on organizing the people the corporate Democrats and Republicans have abandoned for dead.

III. The Mamdani factor

The other major figure to emerge as a prominent DSA member is Zohran Mamdani, who unexpectedly swept to victory in the Democratic Party primary for Mayor of New York City. Coming to grips with the Mamdani triumph should begin with three factors.

- Who he is. Mamdani is the son of immigrant parents — intellectual and creative, hard-working, relatively successful in their pursuits, and with decidedly left-wing inclinations. Young, energetic, determined, he has experience as a social justice activist and organizer. He has been an active member of DSA for a number of years and is considered to be a cadre of that organization. He successfully ran for the New York state legislature more than once, maintaining close ties and consultations with DSA during his election campaigns and during his service in the legislature.8

- What he says. Mamdani is running for Mayor as an open socialist and is unapologetic about his membership in DSA. The platform on which he runs is definitely not a duplication of the platform and various resolutions adopted by DSA, but it is unmistakably a reflection of that group’s general socialist orientation. This is articulated in ways that average working-class citizens who are not socialists can understand and relate to. His message:

Everyone says New York is the greatest city on the globe, but what good is that if no one can afford to live here? The cost of living is the real crisis. New Yorkers are being crushed by rent and childcare. The slowest buses in the nation are robbing us of our time and our sanity. Working people are being pushed out of the city they built.

The establishment politicians don’t care about you — the working class that keeps this city running. Life doesn’t have to be this hard.

- Make buses fast and free.

- Childcare available to all New Yorkers at no cost.

- Freeze the rent for rent-stabilized tenants.

- Create city-owned grocery stores whose mission is lower prices.

- Raise the minimum wage to $30 an hour by 2030.

- Increase taxes on the rich — raising the city’s corporate tax rate to 11.5% will bring in $5 billion a year, and taxing the wealthiest 1% of New Yorkers by 2% will bring in another $4 billion a year.

We can afford to bring down the rent, have world-class public transit, and make enough to raise a family. We can do all of this, and so much more.

Also, Mamdani has been unflinching in his support of Palestinian rights, his opposition — as we have noted — to Israel as a Jewish state (at the expense of the Palestinians), his denunciation of the genocide in Gaza, and his opposition to U.S. government financing and support for Israel’s military operations.9

- The nature of his campaign. New York City DSA co-chair Gustavo Gordillo, who helped organize the Mamdani campaign has explained that the effort focused on “building a working-class coalition that expanded the electorate, that brought in people who had never voted, that increased political participation in a way that no one thought was possible anymore.” Grace Mausser, the other co-chair, who also helped organize the campaign, added: “Thirty percent of the districts in New York City that went for Trump in 2024 went for Zohran in this primary. And it speaks to the fact not only that Democrats are coming out, people who are already registered, but also people who are not registered and are newly activated. They’re the ones who are excited, who want new ideas, who want fresh perspectives.” The campaign was highly organized into such departments as field work, communications (among other things, churning out an amazing array of social media videos), political work (including building coalitions), and fundraising. A sense of the campaign’s scale is indicated in a report by Peter Sterne:

More than 50,000 people signed up to volunteer for Mamdani’s campaign — and more than 30,000 of those volunteers worked as canvassers, knocking doors or [in] phone-banking. (The campaign also hired 40 to 50 specialized paid canvassers, largely to reach voters in less accessible areas of the city and to reach voters who spoke languages that few volunteers were familiar with.) The Mamdani campaign’s volunteers knocked on doors 1.6 million times, which led to 247,000 conversations with voters at their doors. To put that in perspective, Mamdani’s field operation ended up speaking to about a quarter of the total number of people who voted in the mayoral primary.10

One must factor in an additional reality: the Mamdani campaign is up against an incredibly powerful assortment of hostile, well-funded, highly organized political and economic forces, in New York and nationally. Mamdani is now a major target of these powerful forces.11

I have explored complications and contradictions of the Mamdani campaign elsewhere, and some of what I have come up with may be worth repeating here.

One key question remains: Do DSA comrades in New York City — with their strengths and limitations — actually have the power to bring events to a socialist conclusion, or are they now on the verge of reaching the limits of what can be accomplished, given the realities which confront them? Negative realities that I see facing Mamdani and his supporters include these:

- Donald Trump has openly threatened Mamdani and his campaign, should they win the general election and try to implement the campaign’s radical program. Trump very frankly vows to prevent this alleged “Communist takeover” by any means he deems necessary. This would include overturning democracy in New York with a massive invasion of Federal troops, putting the city under martial law, arresting Mamdani (perhaps revoking his citizenship, perhaps deporting him), repressing his followers, etc. If Trump chooses it, decisive sectors of all branches of government would certainly follow him along this path.

- In contrast to socialist and labor parties that exist in a number of other countries, the Democratic Party of the United States is an explicitly capitalist party, controlled by a bureaucratic, elitist machine in alliance with billionaires and multi-millionaires. These proud representatives of the capitalist class are absolutely committed to domination of the U.S. and global economy by the multinational corporations which ensure their own immense wealth and power. If Mamdani proves able to sustain his enthusiastic mass base but is unwilling to compromise his socialist convictions fundamentally, the Democratic Party leadership and apparatus — with all the resources at their command — can be expected to do what they can to prevent Mamdani from taking office and (barring that) from leading New York City down the path indicated in his campaign platform.

- The overwhelming bulk of political news and opinion outlets — print media, radio, television, online, etc. — are business enterprises within which there is a definite slant that favors the capitalist system. This is the case even if the functioning of anti-capitalist radicals is tolerated or, in some cases, even encouraged on the fringes or in the cracks and crevices of the system. Whether in the news media, in the political parties, or in the economy, however, no faction of the billionaire oligarchy (whether liberal or conservative or centrist, and aside from a stray individual here or there) is likely to give way to the assault that Mamdani seems poised to mount on capitalism’s sacred property rights or power.

- If Mamdani continues to have sufficient support to win the general election and remain in office, and if he remains true to his convictions and program, the dilemma remains that New York is a single city within the world’s most powerful capitalist country. This is also setting aside the fact that New York itself is home to Wall Street and happens to be the financial heart of the U.S. capitalist system, intimately connected to that system by innumerable threads. Such facts as these by themselves impose immense limits on what a serious socialist Mayor will be able to accomplish “in the belly of the beast.” If this results in an inability to come through on his campaign promises, his base of support, with the morale and credibility of his movement and the socialist cause, will be in danger of eroding dramatically.

In my previously cited addendum to the Bastille Day “No Kings” interview, I touched on the dilemmas and contradictions that Mamdani faces as he approaches the uncertain conclusion and aftermath of his Mayoral campaign. Soon we will be able to begin evaluating such things, but at the moment I can do little more than repeat now what I offered then:

The question is whether such things as these will prove to be insuperable obstacles or exciting challenges to Mamdani and his movement. Will he end up — as so many on the Left have done — by diluting his program, compromising his principles, and settling for minor accomplishments within the capitalist order, simply to survive and maintain at least some shreds of relevancy? Or will he and his comrades find ways to do better than that? Whatever happens, there will be lessons to learn to strengthen future struggles.

It should be remembered that some defeats can have the quality of victories — if the good fight is fought and morale is high, if compromise is kept within limits and lies are kept at bay, if consciousness is raised and experience gained, if new forces are drawn into greater understanding and activism, if activists and cadres become more knowledgeable and adept at advancing the struggle.

On the other hand, defeats are not necessarily inevitable. It may be that the forces of repression and tyranny will weaken and prove unable to do what they would like to do — or even collapse from their own weaknesses and contradictions. And the ongoing capitalist crisis (which made it possible for Mamdani’s campaign to triumph) may help to generate more insurgencies and socialist victories elsewhere that could come to the aid of “socialist” New York.12

A distinction must be made, of course, between New York City (a populous, cosmopolitan, complex, in many ways unique city) and the rest of the United States. But there are certain similarities that suggest that what can be done in New York can be done elsewhere. There are significant portions of the working class, dissatisfied with the status quo and with the stance of the old Democratic and Republican party establishments, that voted for Trump in 2016 and 2024 but are now being hurt by, and find themselves opposing, some of his actual policies. Mamdani was able to do fairly well among such voters, which suggests that important aspects of what he represents can be relevant beyond New York City.

In trying to make sense of such complex things with which we are dealing, it is essential to understand that two or more divergent things can be true at the same time. This corresponds to a dialectical approach, whose importance Lenin emphasized in understanding reality through “living, many-sided knowledge (with the number of sides eternally increasing).” It is an approach that alerts us to “inner impulses towards development, imparted by the contradiction and conflict of the various forces and tendencies acting on a given body, or within a given phenomenon, or within a given society.”13

The point, however, is to build an effective mass movement for socialism — not only theoretically or philosophically, and not just rhetorically, but also and most importantly on the ground, in real life.

For this, it is independent mass action that is critical — for actually pushing back negative realities, for winning life-giving victories, for providing increasing numbers of people with a sense of their collective power, and giving more and more experience in how to do what must be done to advance the struggle. If a socialist movement is to be built, however, such action must be integrated with a systematic outward-reaching development of socialist consciousness — a sense of our history, of our current realities, of our hoped-for future, and of how we might get there.

Developing such action requires a variety of tactics, including electoral work — but also informational picket lines and rallies, mass protests, strikes, mutual aid efforts, and sometimes even consultations and negotiations with legislators and other authority figures — but also maintaining balance as a result of not overdoing any of these things. A firmness around our socialist and democratic principles and goals should be blended with tactical flexibility, transparency and openness about what we’re doing and why, and ongoing critical analysis about what we face and what is to be done.

Naturally, there must also be an ongoing process of reaching out to draw more and more people into such efforts. There must also be an ongoing process of helping more and more comrades and supporters in becoming adept at such things — developing as socialist cadres to help forge an effective movement.

IV. Socialism and the Democratic Party connection

As we try to comprehend what’s what, and what future actions make sense, it is essential to keep in mind, as best we can, the whirlwind of factors that make up the reality that we are engaging with.

A case in point is trying to understand the Bernie Sanders breakthrough. There were highly contradictory factors involved in this, but for a moment let us focus on the complexities of the positive. Sanders was able to run for the Presidential nomination in the Democratic Party as an open socialist, and through that tilted the political mainstream leftward, helping to create a mass socialist consciousness which — among other things — resulted in a massive influx into DSA.

We will restrict our discussion to five things contributing to this breakthrough.

1. Sanders was able to communicate things that were true. His compelling socialist vision helped him identify such things, with down-to-earth and passionate words that sometimes made him eloquent. Yet these important factors are not sufficient. There have been many who could be described that way, but they’ve been unable to come close to having the impact that he had.

2. Sanders had decades of practical experience as a highly motivated and determined activist and organizer, and this helped him develop the ability to run for and win the office of Mayor in Burlington. He then proved able to accomplish enough as Mayor, and to gain sufficient popularity, to win again and again, and then to run for U.S. Congress, and finally the U.S. Senate — in each case proving able to accomplish enough to win re-election and to move up to a higher office. Combined with the qualities noted in point #1, this made him an unusual figure on the political scene. As Barack Obama once commented, he was “an American original — a man who has devoted his life to giving voice to working people’s hopes, dreams, and frustrations.” There are others who have given voice to such things, but Sanders’ practical experience (seasoned with a socialist vision) enhanced his credibility to the point that he found a unique place on the left fringe of the political mainstream.

3. People were moved not simply by what Sanders had to say, but especially by their own experience: the increasingly oppressive realities of U.S. capitalism — a quite visible ballooning of inequality in wealth and power, an unsettling social instability, a dramatic decline in quality of life. Such on-the-ground realities gave what Sanders had to say a powerful resonance.

4. Almost no one else within the U.S. political mainstream (including in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party) was willing to say what Sanders was saying, in the clear and honest and forceful way that he was saying it.

5. Sanders was a candidate for President to be taken seriously. This credibility was largely dependent on his decision to run for the Democratic Party nomination. Many minor party candidates have campaigned for President before — some of them excellent and eloquent. But they were understood to be protest candidates, not serious contenders for power.

In considering Sander’s choice to run on the Democratic Party ballot-line, with many in and around DSA (such as Mamdani) following his lead, we should remind ourselves, first of all, that the Democratic Party has been a pro-capitalist force from its very beginnings. It is funded and controlled by capitalist millionaires and billionaires, in conjunction with a network of relatively corrupt political machines and a substantial bureaucratic organizational apparatus. It is — absolutely and without question — an enemy of socialism. What is the logic of socialists refusing to make a clean break from this capitalist party?

Running socialists on the Democratic ballot-line can be a tactical element in the realignment strategy, which advocates working within the Democratic Party to eventually shift its platform and policies to the left. But it is not necessarily that. It could be a tactical element in what is tagged a “dirty break” strategy, using the Democratic Party in order to build an effective base for an independent socialist party — when the time is right. But it is not necessarily that, either. It could be an opening tactical salvo in a militant effort to mobilize large sectors of the working class around socialist-inflected demands, in a collision that quickly challenges the capitalist establishment. Or it could be simply connected to muddy political thinking without any clear or consistent strategy.

The fact is that Zohran Mamdani appears — in early September 2025 — on the verge of being elected Mayor of New York City. It also appears that this will have a powerful impact on the future of DSA. It isn’t clear, however, whether he will be allowed by the power structure to win the election, and if so whether he will be permitted to govern or to implement his policies. Nor is it clear whether he will choose to abandon or compromise the program with which he won the Democratic primary. If he wins the general election and assumes office, and if he intends to move forward with what he promised in his campaign, there will be great struggles whose outcome is by no means assured.

Different predictions can be made, in a tone of great self-assurance — but there are some things we cannot know until they play themselves out. In his final published article, as he labored to press forward the struggle for socialism from a position of governmental power, Lenin insisted “we must at all costs set out, first, to learn, secondly, to learn, and thirdly, to learn, and then see to it that . . . learning shall really become part of our very being, that it shall actually and fully become a constituent element of our social life.”14 But he also insisted we must learn through doing — learning through actual struggles against oppression and exploitation, collectively evaluating that experience, and — based on that — thinking through what to do next.

V. Limitations, challenges, and on-the-ground realities

I want to take up some critical points raised by a politically experienced and valued comrade. Some of what he raises strikes me as a bit off-target, although much of it seems quite shrewd and perceptive. Some of his challenges seem to highlight quite different limitations of DSA than those that concern him, and some highlight my own lack of knowledge. I should emphasize that while I attended the recent National Convention in Chicago, most of my practical experience has been in Pittsburgh — and most of that has been only over the past year or so. I cannot yet say with assurance how much the Pittsburgh experience matches what is happening in other parts of the country. But let us begin, responding to six concerns.

1. My friend writes that “the orientation toward the Democratic Party continues to be the practice of most DSAers” although it is not clear to me what this observation is based on. I haven’t been actively involved in DSA until recently, in my native Pittsburgh, but here the electoral fixation seems to be absent. I certainly noticed no local DSA engagement in the Presidential campaign of 2024. My friend adds that “emphasis on local elections almost always means as a Democrat, which means getting deeper and deeper into that dead end.”

But my limited experience in Pittsburgh indicates something else. I am aware of several times when our chapter has had consultations and general meeting agenda points about a “progressive” Democrat or a Green (or in one case an African American leftist running as an independent) requesting a DSA endorsement — which is considered and sometimes forthcoming. In my short time of involvement, however, this generally turns out to be a paper endorsement, with perhaps a financial donation and a few comrades helping out, but not a mobilization of our membership drawing us “deeper and deeper” into the Democratic Party (or the Green Party or electoralism as such). A partial exception involved the local black socialist running as an independent — did get more actively involved, and he seemed to have a chance of winning. But he lost, with about 30% of the vote. Annoyingly and painfully relevant to our situation here is the passing comment from Maurice Isserman that DSA is “not particularly well-organized.” I imagine a different situation elsewhere, and I am cautiously hopeful that the situation will improve in Pittsburgh as well.

2. The comrade comments that “the Mamdani victory will only encourage” being swallowed by the Democrats. Yet this actually implies one of two developments. If a Mamdani victory encourages DSA chapters in places like Pittsburgh to get more seriously organized (even around electoral work), that might have a positive side, since the more coherent organization could also strengthen non-electoral efforts. On the other hand, if Mamdani is not victorious, or if he wins the election but is defeated either by the capitalist power structure or by his decision to compromise with that power structure, different and more radicalizing lessons might be learned, leading away from the Democratic Party.

3. The comrade also makes this quite valid point: “When Rashida talks about the Democratic Party being a party funded by billionaires and sees no problem in being part of it, there is a problem.” Yet two things occur to me: (1) Maybe she sees a problem but chooses not to make a rhetorical point about it (which, one could argue, is still a problem). And (2) what she is saying has a definite educational and radicalizing impact, which may intensify in the minds and hearts of people over time — leading away from the Democratic Party.

4. The comrade writes that “the much larger radicalization of the Vietnam era, nevertheless, ended up in the Democratic Party,” and asks "what is to prevent DSA's continued orientation from leading to something similar?” Here also, two things occur to me — one about the relationship of past to present, another about the relationship of present to future.

- Past/Present. It is certainly true that many who were part of the amazing radicalization of the Vietnam era (1960s and 1970s) ended up in the Democratic Party. Yet there was more than simply that. We all learned so much as we lived through experiences which not only transformed many of us personally but also transformed our culture and consciousness. This helped make possible a continuation and expansion of struggles over the years that in an earlier time would not have unfolded as they did.

- Present/Future. What is to prevent the future of the present generation from simply replicating the future of the past generation? Overlapping with points just made about cumulative transformations of consciousness and culture, there are substantial differences in the capitalist system as well as the Democratic Party since the 1960s-70s-80s-90s. This precludes a simple replication of what happened before. Although some similarities are possible regarding what happened yesterday and what will happen tomorrow, different likelihoods and new possibilities seem to be coming into play.

5. My friend comments at length on a Jacobin interview with Grace Mausser and Gustavo Gordilio, key organizers for Mamdani's election campaign. He notes that they “essentially argue they have turned much of the huge NYC DSA chapter into an electoral machine in the Democratic Party — rival to the [machine of the Democratic Party] establishment of course.” While this may be true, two things impressed me.

- The massive, intense, systematic effort to reach outwards and talk about what is happening in our country, involving such large numbers of people — face-to-face, listening to what they had to say, discussing with them the problems of New York and what the Mamdani campaign hopes to do about those problems.

- The high degree of organization, commitment and participation in this campaign among those in and around NYC DSA.

6. Very much on-target, it seems to me, is my friend’s observation that “Mamdani himself is very up front about being a loyal Democrat, no doubt out of necessity to get elected.” Both troubling points are true. And as the comrade adds, “something similar may be happening in Minneapolis where they are running for Mayor.”

There are a number of unanswered questions. My own belief — largely shaped by conceptions advanced by Rosa Luxemburg, and by Lenin and his comrades, as well as by more than 60 years of my own experiences — is that independent mass action is key, combined with systematic development and spread of socialist consciousness. This must also involve the accumulation of activists and of cadres, which in turn involves the larger accumulation of knowledge, understanding, experience, practical skills.

The path forward is through opposing oppressive realities, maintaining an activist focus, working for positive alternatives, while developing, expanding, and deepening socialist consciousness. This means considering a variety of options and working our way — through active engagement — toward what makes sense. I think Rashida Tlaib is right: this is our moment — a moment of facing challenges, of grappling with complexities, and of learning, learning, learning. And with all its limitations and ambiguities, DSA is a central element of that collective process.

We need to factor an additional element into our thinking — that of urgency. We do not have all the time in the world. Two Portuguese revolutionaries associated with a group called Climaximo, writing of the climate change now threatening human existence, put it this way:

Given [that] we need to execute system change in this decade, what are this week’s deliverables that are compatible with such a plan? What are in today’s to-do list according to that plan? What kind of global movement do we need to undertake such a task? What do we need to provide in the next months?15

Such thinking can — of course — lead to despair, or to desperate acts that would wreck a movement and burn-out its survivors. It must, instead, be connected to the real-world dynamics of what we can actually do. As Lenin put it, we must commit ourselves — and then see . . .

- 1

For a valuable historical overview, see Laura Wadlin, “A Political History of DSA, 1982-2025,” in Stephan Kimmerle, Philip Locker, and Branden Madson, eds. A User’s Guide to DSA (Seattle: Labor Power Publications, 2025), pp. 48-57. For a snapshot of the 2025 DSA Convention, see Paul Le Blanc, “Learning from the DSA Convention,” International Viewpoint, 16 August 2025, https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article9127

- 2

Maurice Isserman, The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington (New York: Public Affairs, 2000); Doug Greene, A Failure of Vision: Michael Harrington and the Limits of Democratic Socialism (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2021). It is also worth noting that the word “comprehend” means more than simply understanding – it suggests an active engagement, an act of embracing.

- 3

Michael Harrington, “Is Carter the Lesser Evil?” (debate with Peter Camejo, 1976), in Duncan Williams, ed., The Lesser Evil? Debates on the Democratic Party and Independent Working-Class Politics (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1977; 2021), p. 54.

- 4

Ibid., pp. 14, 17.

- 5

On the early development of the realignment strategy, see Paul Le Blanc and Michael D. Yates, A Freedom Budget for All Americans: Recapturing the Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in the struggle for Economic Justice Today (New York: Monthly Review, 2013), especially on pages 56-57, 61-69, but throughout the study.

- 6

Greene A Failure of Vision, pp. 3-4.

- 7

Michael Harrington, Toward a Democratic Left: A Radical Program for a New Majority (Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1969), pp. 186-215.

- 8

See also the loud, brassy, but informative video on Mamdani: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T-_RVOQEFXQ

- 9

A short, snappy campaign video, “Zohran for NYC” can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzNEFwLz6C4; For Mamdani’s victory speech upon winning Democratic nomination for Mayor see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7v8evcIoBN8; also see his talk “Why I Joined DSA,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2WJOQPJUc8Q; and the CNN interview https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BUfJmg-8gyM.

- 10

Sam Lewis (interviewed by Stephan Kimmerle), “The Soul of the Machine,” Kimmerle, Locker, Madson, eds., A User’s Guide to DSA, pp. 217-228; Peter Sterne, “Here’s how Zohran Mamdani’s 50K-strong volunteer army pulled it off: interview with Tascha Van Auken, field director for Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign,” City and State (New York), July 1, 2025, https://www.cityandstateny.com/personality/2025/07/heres-how-zohran-mamdanis-50k-strong-volunteer-army-pulled-it/406464/.

- 11

Mamdani on Trump attacks: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/4O2b6IbCuV8; more generally, “Zohran Mamdani Remains the Candidate to Beat,” Newsweek, August 21, 2025: https://www.newsweek.com/zohran-mamdani-remains-candidate-beat-cuomo-adams-slide-poll-2116718.

- 12

Ibid.

- 13

Quoted and discussed in Paul Le Blanc, Lenin: Responding to Catastrophe, Forging Revolution (London: Pluto Press, 2023), pp. 72-73.

- 14

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, “Better Fewer, But Better,” Collected Works, Vol. 33 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1965), pp. 488-489.

- 15

Mariana Rodrigues and Siran Eden, All In: A Revolutionary Theory to Stop Climate Change (2025), p. 58.

The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) entered its 2025 National Convention at a crossroads: the largest socialist organization in the United States in generations, gathering in the midst of a rising fascist threat and a diffuse but determined wave of multiracial resistance. With nearly 1,300 delegates in attendance, the convention could have been a decisive moment to chart how DSA might “meet the moment”—to orient its chapters, campaigns, and national leadership toward building mass, working-class based power in defense of democracy and for socialism. Instead, what unfolded revealed both the organization’s enormous potential—its energy and enthusiasm, its attraction to new generations of revolutionary activists, its broad range of campaigns—as well as its deep limitations: a culture of performative factional combat, a national leadership paralyzed by electoral abstentionism and “left” sectarianism, and a gathering that too often turned inward rather than rooting itself in DSA’s own mass-based practical achievements and the urgent tasks before us.

This article reflects on that experience, drawing from both the convention floor and the lessons of earlier socialist movements, to argue that DSA now faces a stark choice: it can turn outward, grounding itself in wide-ranging mass struggle and broad coalition-building, or it can continue down the path of sectarianism and paralysis—squandering a historic opportunity to meet the political moment.

Having only been a DSA member for around 18 months, this was my first Convention; I attended not as a delegate but an observer, and I paid attention. After 40-odd years of union conventions, this was different (and not only in the politics): less staged, more youthful, more diverse in gender (if not in race), better parties, and overall more exciting. On the other hand, it was less well-organized and less well-run, largely due to an internal-facing agenda, an absence of focus on practice, an inconsistent and sometimes sectarian use of Robert’s Rules, and a complete failure of voting tech. And it was even more factional, which is saying something.

Bernie’s Garden

Today’s DSA is the house that Bernie built. It was his 2016 campaign—his open democratic socialism, his populist working-class economic program, his willingness to skewer neoliberal Democrats and Republicans alike, and his ability to win—which captured the imagination of a new generation of socialist-minded activists (some reformist, some revolutionary) and laid a new foundation in place of the somewhat decrepit Michael Harrington one. Today the house has many rooms (with a front door likely barred to Bernie), and the garden soil has proved incredibly fertile to the growth of innumerable factions, called “caucuses”—each of which, and each differently, has deep roots in U.S. and international revolutionary traditions.

In an organization dominated by factions, I of course have my own favorites. I am a lightly active member of the Socialist Majority caucus, and a sometimes fan of the Groundwork caucus (especially when they can rein in their subjectivism; see below and in the Appendix). Together they represent the self-identified “mass politics” caucuses: factions which emphasize creative outward-facing mass organizing and contestation for power on all terrains of class struggle—from the workplace to the community to the electoral. Where DSA has had impressive success building independent political organization, it is these caucuses—especially the Socialist Majority caucus—which have been largely responsible.

On the other end of the spectrum are the more “vanguardist” caucuses (they would likely say “revolutionary”) such as Red Star, Marxist Unity Group, the Communist Caucus, and Reform and Revolution. In general, they seek (in practice if not always in theory) to turn DSA from a very broad mass socialist organization with a low level of unity into a narrower vanguard party organization with a much higher and more restrictive level of unity. Some have sophisticated ideas about how that might happen and what it might achieve, while others seem more interested in posturing. On this end of the spectrum, but with somewhat more anarchist-inspired politics is the newer and smaller Springs of Revolution, as well as the venerable and annoying Libertarian Socialist Caucus, which draws explicitly from anarchist roots.

The main caucus between these two poles is Bread and Roses, which draws its inspiration from the very experienced and long-lived (since 1986) Solidarity socialist organization, from Kim Moody’s “rank and file strategy,” and from the ever-brilliant Labor Notes project. Bread and Roses’ greatest strength is its dedication to rank and file workplace organizing, including directing young DSA members with little working-class experience into lifetime working-class jobs and associated organizing projects. Its greatest weaknesses are its syndicalist fixation on a “rank and file” tactic which does not amount to a true strategy, and its ambivalence towards class struggle on the electoral terrain. (Also between the two caucus poles, but drawing from very different ideological traditions than Bread and Roses, can be found the newer and smaller Emerge caucus, largely based in NYC and still defining itself.)

I have heard it said many times that 80% of DSA members are inactive (some caucuses dismissively call them “paper members”), which if true suggests that the nearly 1300 convention delegates were there representing at most 15-20,000 active members. I’ve also heard it said that only around 10 to15% of those active members are actually caucused. But the caucuses, representing the most ideologically aligned and internally organized members, clearly dominated the delegate elections and the Convention itself. My sense is that only around 20% of the delegates were ideologically independent—that is, uncaucused and relatively unaligned. As it turned out, the spontaneous tendency among the majority of that ideological center was to lean towards the ultraleft.

Meeting the Moment

I grew up in the so-called “New Communist Movement” of +the 1970s and ‘80s. The numbers in organizations large and small were similar to the number of active DSA members. Having come out of the mass movements of the ‘60s (mainly the anti-war movement, the civil rights and Black liberation movements as well as the Chicano, Puerto Rican, Asian-American and Native American national liberation movements, the women’s movement, and a very embryonic gay liberation movement), born in the shadow of a splintered SDS and a Communist Party which seemed to have capitulated to both U.S. capital and Soviet imperialism, and witness to the murders of Civil Rights activists and revolutionary leaders such as Fred Hampton, our experience was very different from that of today’s young revolutionary socialists raised in the shadow of neoliberalism. While the racial/national composition of our movement was quite different from today’s DSA, and the factory and other industrial employment opportunities were much greater for aspiring revolutionaries, our social base was quite similar to that of DSA: petit-bourgeois middle strata, often fresh out of college. And our movement, despite its many impressive achievements in mass working-class struggles and organization-building, was ultimately wrecked by a deep-seated and wide-ranging ultraleftism. That experience cannot help but color my impressions of the DSA Convention.

At the Convention (and in public reports since), there was much talk of “meeting the moment,” but what is “the moment”? Our “moment” today is mainly characterized by a minority but still mass-based federally led and enforced drive towards fascist autocracy; a broad, diffuse and largely uncoordinated resistance front; a labor movement and movements of oppressed nationalities all struggling to rise to the challenge; and an energetic but disunited socialist left lacking deep mass roots. And we don’t have much time: this particular moment will last only around three years, after which conditions will either improve somewhat or become much, much worse, worse in ways many of us have never experienced.

At the level of national leadership, DSA clearly failed to meet the moment throughout 2024 and up to the present date, mainly because it was afflicted with a divided and sometimes paralyzed National Political Committee with a slight majority of electoral abstentionists. One of the few national successes of DSA during 2024 was in fact the “Uncommitted” campaign, largely led by the so-called “mass politics” factions, and later denounced as a failure by sectarian abstentionists (some recently returned to leadership positions), despite its enormous positive effects on popular opinion. In 2025, the one success with national significance has been the astounding victory of Zohran Mamdani’s brilliantly-run campaign—also largely initiated and led by the “mass politics” factions. During this period overall, it seems that only strong chapters, operating independently of national guidance and encouragement, and engaged in dedicated and creative mass organizing, were able to “meet the moment.”

So what was ultimately at stake in DSA’s 2025 Convention? What does “meeting the moment” mean, not in general, but today, and not for just anyone, but for an organization as large and potentially influential as DSA? To my mind, it means turning away from sometimes overly comfortable left spaces and towards working-class communities and workplaces; it means developing campaigns on every available terrain of struggle which broaden and deepen the front against fascist autocracy while centering fights against the ethnic cleansing of immigrants, against the wiping out of the gains of the Civil Rights movement and Black Lives Matter upsurge, against the attacks on trans people, and against the genocide in Palestine; it means working closely with all left/progressive organizations and activists who are committed to developing left leadership of the front independent of establishment Democrats; and it means working closely with all socialists committed to these efforts in order to help coordinate the resistance and turn its eyes towards the future.

How did the Convention measure up to these (admittedly lofty) standards? Some reports internal to DSA show that there is an irresistible desire to look on the bright side while avoiding any negative conclusions, especially where the fate of the authors’ particular caucus is at stake. See, for example, the 8/26/25 Groundwork caucus message to supporters, entitled “

Thorns

The Convention’s most glaring weaknesses can be summed up in three failures: a failure to ground itself in practice, a failure to center the fight against fascism, and a failure to build unity against ultraleft tendencies in the organization.

First, an extremely important defect of the Convention was its failure to base the proceedings in the organization’s practical successes of the previous two years; any unionist could have told the Convention Committee that. Most of the public commentary on the Convention unsurprisingly emphasizes the great significance of the Mamdani victory just prior to the meeting; what few if any mention is that there was almost no actual discussion of that campaign during the proceedings—at one point, one of the Convention chairs even warned against referring to the Mamdani campaign as being “off topic.” Why didn’t the Convention lead with video and panel discussions of practical efforts such as the Uncommitted and Mamdani campaigns—the most high-profile DSA efforts of the past two years? When there was finally a panel discussion of the successes and challenges of the Mamdani campaign—and a fascinating one, populated by organizers who really knew what they were talking about—why was it scheduled for Sunday at 9 am, when at most 2% of the delegates were in attendance?

Second, overall there was very little attention to—or even mention of—the Trump drive towards autocracy. Of course there were references here and there, but the Convention in no way centered this obvious pressing danger to the left, the working class, and the people’s movements. The one resolution which most clearly centered this danger and addressed it strategically (R24: To Defeat Trump, Turn Toward the Masses), authored by Socialist Majority caucus members from New Orleans, New York, and Boston, offered this cogent summary:

Our primary task at this moment is to defeat the far right. To do this, this resolution proposes taking a nonsectarian approach to uniting with groups that are mobilizing working people into action to protect lives and democratic rights. Even as we work together, we will contest for socialist leadership of the anti-fascist front’s strategy. DSA will demonstrate that socialist politics and organization are the best path forward for striking blows against the capitalist class and the far right.

Yet despite having received a 59.29% approval rating in the pre-convention delegate survey, this resolution, which came closer to “meeting the moment” than any of the other 100-odd proposals, was placed well down on the “overflow agenda,” ensuring that it would never reach the Convention floor. Well above it on the regular agenda were numerous internally focused items, including R08: Democratic Discipline: A Uniform Process for Electoral Censure Across DSA (48.40% approval rating) and R47: Resolution to Censure U.S. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (30.33% approval rating). Sadly, I’m pretty sure the reason is that there were those on the Convention Committee who feared that giving greater attention to this stunning organizing victory would provide sectarian advantage to the ”mass politics” factions which had the most to do with its success. And Instead of orienting outward to the urgent political struggles that define this moment, the Convention doubled down on inward-facing disputes, leaving its resolutions disconnected from the realities of mass organizing.

Underlying both of these missteps was a deep-seated ultra-leftism, which misunderstood the strategic tasks of U.S. socialists today while encouraging performative ideological combat over political debate rooted in both the perils of this moment and the DSA’s main practical achievements of the past two years.

One could also ask why there was so little attention to practice in general at the Convention—summations of actual work, grounded debates around practical experience and choices, organizing priorities and so on—and I can’t do better than paraphrase a longtime unionist friend who also attended the Convention and observed that having been attracted to the idea of socialism right out of school, rather than having been driven to it through practical organizing or life experience, a fair number of DSA delegates seemed more comfortable with performative internal combat than with the deep and dirty work of the class struggle. Shades of SDS….

Well, There’s Always the NPC Election…

It’s not hard to understand why many in DSA suggest that what really matters at Convention is the balance of power on the new National Political Committee. There’s no way even a united NPC could take the many conflicting resolutions (see the Appendix to this article for a discussion of some of these) and fashion a unified, consistent program–and with a divided leadership, it’s every chapter for itself.

Unfortunately, the new NPC, despite some improvements, will likely continue the confusion and paralysis of the previous one. It’s important to note that, while some ultraleft factions took some hits in the election, the leading vote-getter in the three-way election of co-chairs is someone who, in a rehash of the discredited but not-dead-yet 1928 Comintern “social-fascism” thesis, stated in August of 2024 that “…the primary options during this election year are Neotrad Fascism vs. Woke Fascism….” And despite having just a few years earlier been an Elizabeth Warren supporter, in an NPC Steering Committee call she is reported to have accused Zohran Mamdani of “sheepdogging” voters into the Democratic Party—much like the Green Party had called Bernie Sanders “a sheep dog for the Democrats,” reducing millions of working-class voters to “sheep.” Has this co-chair paid a price for this? Has she been asked how she, DSA members, and the masses generally are enjoying “Neotrad Fascism” today? Or whether the stunning achievements of NYC DSA members in the Mamdani campaign were all a big reformist misdirection? It doesn’t seem so, since the spontaneous drift of Convention delegates was so much to the ultraleft. Yet if anything, this NPC co-chair is in danger of “sheepdogging” DSA members into irrelevance.

For a deeper understanding of some of these underlying tendencies, I recommend reading with today’s eyes this post-election statement from the Red Star caucus, which captures well the “ultra” line on the 2024 election.

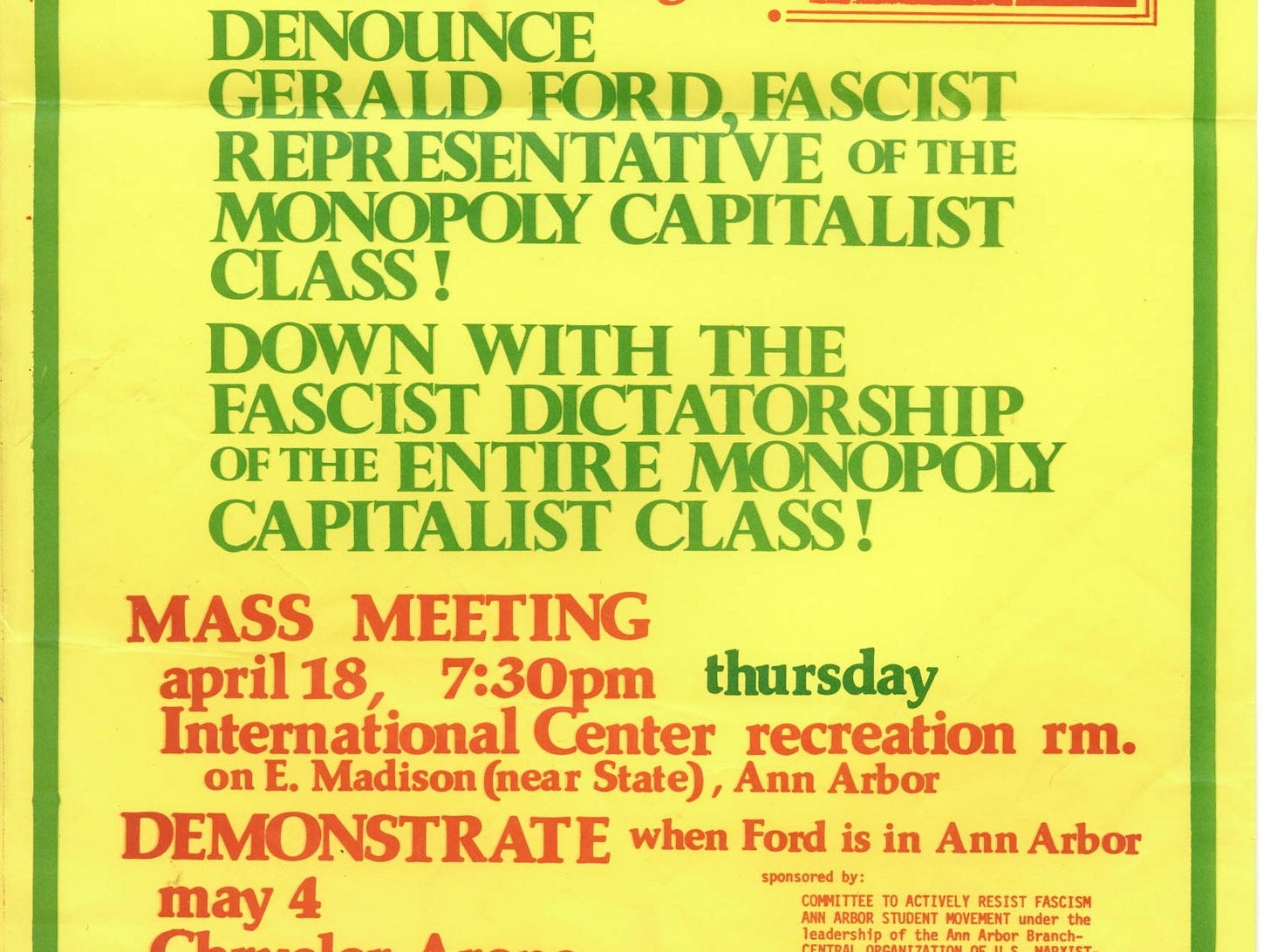

Old as I am, I can’t help but think of the many Marxist-Leninist organizations of the mid ’70s and early ‘80s that described left liberals and social-democrats as “ushering in” fascism–as if they stood at the political theater door, murmuring “Right this way, sir.” Workers Viewpoint, for example (which later became the Communist Workers Party of the infamous Greensboro Massacre), described Leon Davis, founder of 1199, this way: “Leon Davis and the 1199 misleaders help to usher in fascism in many other ways. Their support for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) shows this clearly” (July 1976). Aside from misunderstanding both Carter and Reagan as fronts for fascism, and aside from misunderstanding the Democratic Party as just a paper mâché cover for the Right, and aside from updating the wrongheaded Comintern “social-fascism” thesis, there was a hidden assumption common to nearly all ultraleft tendencies: that the masses are a caged beast waiting to spontaneously explode, if only they can be released (by a “hammer” perhaps) from their captors.

Sometimes class struggle works like that, but not generally, and not here and now. Leading it actually requires an understanding of complex contradictions, a ton of concrete analysis of concrete conditions, a ton of political education, and a ton of daily mass organizing on generally hostile terrain. There’s a big difference between Marxism “fusing” with the workers movement, and Marxism “releasing” the workers movement.

Red Star and similar tendencies are part of a 150-year-long tradition of dead-end ultraleftism, and as they defend and develop their line they cannot help but draw from the deep well of that semi-Marxist, semi-anarchist deviation. And if allowed to dominate DSA, they will certainly destroy it.

Living With Ultraleftism

The fact that DSA’s national leadership (despite valiant efforts of the minority) made itself irrelevant or worse in last year’s federal election, which brought fascist autocracy as close to consolidation as it is, that it has made itself largely irrelevant in the immediate aftermath, and that a national co-chair could publicly revive the disastrous “social fascism” line of the 1928 Comintern and be exalted at the next Convention–in the very teeth of autocracy–indicates what a wellspring exists in DSA today not of revolution (as one “left” caucus would have it), but of ultraleftism. Unfortunately, in the petri dish of DSA’s predominant social base (downwardly mobile college-educated activists from middle strata backgrounds), mixed with the repression people of color (immigrants and citizens alike) are already facing and the Left as a whole will soon experience, those ultraleft tendencies are likely to grow.

Key to working with these tendencies—which means uniting with them where possible, and neutralizing their influence where they threaten to undermine our mass movements and organizations—are:

- Learning more about what ultraleftism is all about, as a longstanding and destructive deviation from Marxist theory and practice;

- At the same time, focusing outward, turning “toward the masses” (as Socialist Majority put it in the resolution which was kept from the floor by the ultras), among whom comrades new to socialism and attracted to ultraleftism will often learn, develop some humility, deepen their understanding of the working class, and become socialist organizers whose revolutionary influence will grow; and

- Use the truly impressive organizing experience of the outward-facing tendencies and chapters of DSA to help orient, solidify and grow smaller chapters which may not have figured out yet how to escape the hothouse atmosphere of internal ultraleft politics and transition to a more mass politics and rank and file focus.

The risk is that what should be a minor internal contradiction as compared with that between socialists and the establishment Democrats, if unaddressed, will grow to prevent DSA from ever meeting the moment. Chapters investing in deep mass organizing (rather than posturing) will have to do more than out-organize the ultras; as that contradiction sharpens, they will have to learn to recognize, expose, isolate, and neutralize them in order to save DSA.

My sense of the result of this DSA Convention is that DSA as a national organization with enormous potential will be hamstrung by deep ideological divisions concerning the main tasks of today’s socialist left. Simply put, the new National Political Committee will be incapable of meeting the moment, no matter how much triangulation and compromise occurs within its ranks.

The good news, though, is that the NPC will be equally incapable of preventing strong chapters from rising to meet the moment. Therefore, investing in building those chapters while essentially ignoring a paralyzed leadership will be critical to broadening the antifascist front and building strategic, mass-based (and reality-based!) socialist organization within it.

Those chapters can ramp up the struggle for Palestinian liberation from Zionist occupation and genocide while broadening it to include everyone who is willing to oppose the genocide, whatever their position on the nature of the Zionist state. They can focus outward on mass struggles which challenge the fascists’ attempts to restore and restructure white privilege, whether that’s centering direct struggles against ICE, building up labor’s resistance to mass deportation, organizing against the DC, Baltimore and Chicago occupations, defending and embracing those who tell the truth about U.S. history, or running candidates who can skillfully combine a populist economic message with a clear and fearless attack on the racist mortar which cements the fascist coalition. They can build popular movements to defend trans rights and bodily autonomy, and help grow and lead the widespread mass struggle for women’s reproductive rights. They can build independent political organization in blue, purple and red states, fielding and supporting left candidates (and socialists wherever possible) who are serious about mass-based progressive governing power. They can help build union locals which embrace the rightful role of labor in the broad front against fascism. And they can build socialist organization which meets the moment.

Appendix: What Did DSA Resolve To Do?

It’s reasonable to ask whether the many Convention resolutions passed mean anything in practice, and to suggest that the only thing which actually matters is the balance of power on the National Political Committee. But the resolutions have a lot to teach us about tendencies in DSA, and when adopted they can also be used on an ad hoc basis either to legitimize and guide chapter work, or conversely, to punish chapters who balk at carrying out dumb directives. With an eye on “meeting the moment,” it’s worth taking a look at some strengths and weaknesses of some resolutions which attempted to address our strategic moment and which actually passed.

A number of resolutions which give form and content to DSA’s mixed commitment to fighting the fascist threat passed as part of the large “Consent Agenda,” which is to say with little or no discussion. Let’s first take a look at some of those.

(CA)R05 “Fight Fascism, Build Socialism” (authored mainly by the Groundwork caucus)

Here there is specific mention of Trump and the fascist threat—all to the good:

DSA can be the weapon against fascism that millions are desperately searching for. This resolution turns our ad hoc Trump response into a focused national campaign, with resources and a clear mission needed to fight the right.

Note the word “the” in the first sentence; it does a lot of work there. Imagine if instead of “the” it said “a”, injecting a note of objectivity (and even humility). (This is where some DSA leaders will say out of one side of their mouth “we are the largest socialist organization in 100 years,” and out of the other, depending on what’s being debated, “80% of our members are paper members!”) In the 1970s and ‘80s, every single self-declared “party of a new type” asserted that they were THE weapon that millions were desperately searching for, only to end up like little commie Ozymandiases.

While there is great stuff in the resolution about organizing resistance at all levels and building the “Left” to do so, it is immediately undermined by a narrow, sectarian understanding of who the “Left” is:

Defeating the far right requires more than just fighting back—it requires building the Left. DSA must use this moment to massively grow our ranks, train new leaders, and build organizational infrastructure capable of sustaining a long-term struggle for socialism.

Socialists cannot rely primarily on existing institutions to resist authoritarianism. NGOs, Democratic-aligned advocacy groups, and progressive organizations have consistently failed to provide strong opposition to the right. Defeating the far right can only come from an organized majority of the working class. DSA must fill this vacuum by leading a truly independent, working class fightback.

Of course we can’t “rely primarily on existing institutions to resist authoritarianism.” And certainly some—even many—NGOS, Democratic-aligned advocacy groups, and progressive organizations have “failed to provide strong opposition to the right”—just as DSA itself has in many cases, especially at the national level. What’s missing here is any recognition of those sections of the left/progressive bloc which are attempting—and in some cases succeeding (Indivisible, anyone?)—to provide strong opposition to the right. And this reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature and breadth of the front actually necessary to defeat—or at least push back—fascist autocracy over these next three years. And with a misunderstanding of the breadth of the front, comes pure fantasy about DSA filling “this vacuum” by “leading” “an organized majority of the working class” in an “independent, working class fightback.” Simply put, that’s not happening any time soon, so how can we actually fight the right today and tomorrow?

In that regard, this resolution provides some excellent direction for DSA chapters in Blue areas:

Despite the extreme threat posed by the Trump administration and the far right, the Democratic Party remains a primary political opponent of the working class in the Democratic controlled states, cities, and districts where DSA is often strongest. Fighting the far right means resisting capitulation by Democratic leadership in these areas, winning back working class people (particularly young people and people of color) in Democratic strongholds who have flipped to Trump or fallen out of participating in politics entirely, and ultimately winning local level socialist governance in our strongest areas.

Unfortunately, it provides virtually no direction to DSA chapters in purple and red areas. Are we to assume that socialist power-building tactics are identical regardless of the nature of the terrain on which we fight? That’s dogmatism, not Marxism.

(CA)R18 “Seize the Moment! Defeat Corporate Democrats and Elect More Socialists”