AMERIKA

'There is no Christmas for separated families': Pastors tend to immigrant families in crisis

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — As Los Angeles pastors lead congregations and preach about the meaning of Christmas, they’re facing the emotional devastation of families struggling to cling to hope.

A Christmas Nativity scene portrayed as a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center sits on display in front of the Oak Lawn United Methodist Church, in Dallas, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

Aleja Hertzler-McCain

December 23, 2025

RNS

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Nine days before Christmas, a group of clergy huddled around a young mother outside the Los Angeles Federal Building, praying for a Christmas miracle that a judge would set bond for her husband at a hearing the following day and release him from immigration detention.

Melanie, 21, who agreed to speak to RNS on the condition that only her first name be used, has been nursing a hope for months that her husband, an immigrant from Nicaragua, would be back home in time to celebrate their infant twins’ first Christmas.

In July, as her husband prepared for an Immigration and Customs Enforcement check-in at the federal building, Melanie was confident he would be spared detention because, she told him, “we’ve been doing things right.” Leaving nothing to chance, she decided the family would go to the check-in together. Surely, she thought, they wouldn’t detain him in front of his wife, a U.S. citizen, and three kids.

But after her husband had filled out forms and answered agents’ questions about his tattoos, he was taken into a separate room. After 15 minutes, “ all of a sudden, I hear him screaming my name,” Melanie recalled.

Running to him, she saw he had been handcuffed. “ I felt like the whole world just fell on top of me,” she said. With her kids watching, the agents “cornered” her, not letting her approach her husband or say goodbye, but she said, “ I could just tell in his face that he was scared.”

Within five minutes, she was escorted out into the hot July sun. Without their father, there weren’t enough hands to carry the twins’ car seats and her toddler daughter.

The Revs. Carlos and Amparo Rincón post a video to social media from the Metropolitan Detention Center in Los Angeles. (Video screen grab)

It was there, stranded on the sidewalk, that Melanie met the Revs. Amparo and Carlos Rincón, married Pentecostal pastors who belong to a network of Los Angeles faith leaders who are supporting families broken apart by the Trump administration’s mass deportation policies.

“She looked younger than my daughter,” said Carlos. His wife approached the crying mother, whose eldest was inconsolable after what she had witnessed. The Rincóns have since helped Melanie with diapers, baby formula and groceries, in addition to praying for her and offering to pay her 25-year-old husband’s bond through Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, colloquially known as CLUE.

Amparo and other women lead an interfaith group with CLUE that meets every Tuesday to march in prayer around the federal building, a center for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The group calls itself the Godmothers of the Disappeared.

Melanie’s family is just one of many the pastors have found on their weekly visits. Carlos Rincón said his church, which he asked not be named out of fear of retaliation, is supporting about 25 families. One woman, a wife separated from her detained husband, texted RNS in Spanish: “There is no Christmas for separated families.”

Carlos and another group of pastors with his organization Matthew 25, alongside CLUE, plan to break away from their other pastoral responsibilities on Christmas Eve to hold a vigil outside the downtown ICE center, preaching one of his central messages that “ God himself experienced what immigrants experience.”

Detainees at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Eloy Detention Facility in Eloy, AZ. (Photo by Charles Reed/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, File)

Even so, he acknowledges, “it is hard.” He said, “ there are too many needs and too many people in so many difficult situations.”

As Advent came and the Rincóns preached about the meaning of Christmas, they faced the emotional devastation of families struggling to cling to hope. It wasn’t until Dec. 1, when Olga, a worship team leader, learned her husband had been detained, that the detentions affected the church directly.

Since then, Olga wakes up too depressed to sing. She’s having trouble eating and sleeping. Despite that, she said in Spanish, “I try to go (to church) because I know God is the one who gives me the strength to continue. He is the one who is with me every day.”

But still, Olga said, “because of what we’re living through, I don’t have a head to think. It doesn’t feel like it’s Christmastime.”

The Revs. Melvin and Ada Valiente. (Courtesy photo)

The Rev. Ada Valiente, who supports at least 30 separated families with her husband, Melvin, through their We Care ministry, said that several mothers are suffering a mental health crisis. Struggling to make practical plans to address their immediate needs and unable to plan for their future, they have little time to think about celebrating Christmas.

The Valientes, who lead two American Baptist Churches USA congregations in Los Angeles County, hear about families in need of support from other pastors, other immigrants in the detention centers or sometimes the families themselves.

While the couple will offer advice and recommend reliable immigration attorneys to anyone who reaches out, they prioritize the people with the highest needs — detainees with no family, or whose family cannot visit them because they lack legal status themselves or lack resources. Holistic support provided may include prayer, financial assistance or visits to detained and separated family members.

Melanie and an immigrant mother under the Valientes’ care who requested anonymity because she lacks legal status both said they had been charged thousands of dollars by immigration attorneys who made no effort to help the detained men.

In the months since Melanie’s husband was detained, she has managed to finish his active construction contracts. She had to give up their first apartment and move back in with her mother, who helps with the kids. Melanie also followed the legal details of her husband’s case until she found a new attorney, who was willing to sleep in the detention center’s lobby in order to see her husband.

Melanie met her husband in 2022, when her Nicaraguan mother threw a birthday party for the newly arrived fellow Nicaraguan, who had crossed into the United States legally via the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s CBP One app. He was granted parole while seeking political asylum.

She said her husband is requesting asylum based on his claim that he was wrongly incarcerated in Nicaragua for two years before being pardoned. “He was just at the wrong place at the wrong time,” she said. He’d already applied to be a permanent U.S. resident before he was detained in LA.

Several of the other women receiving help from the Rincóns and Valientes also fled the human rights crisis of Nicaragua, where co-Presidents Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, have decimated civil society, including religious institutions, and instituted authoritarian rule. One woman told RNS her detained husband had been arrested, beaten and threatened with worse after participating in a march. They fled Nicaragua, leaving their children behind with relatives. When her husband was detained in the U.S., he was still in need of medical care for injuries from his beating.

Another woman told RNS that she and her now-detained partner refused to join the Ortegas’ socialist Sandinista Party because of their Christian faith, despite threats of physical harm to them and their son. Unless they joined, they were told, they would not be protected by the police. Twice, her husband was detained without cause in Nicaragua, she said.

Both women asked for anonymity because they fear deportation.

Ada Valiente, whose brother was a political prisoner of Nicaragua’s conservative Somoza dictatorship, fled with her family to the U.S. when she was a child, arriving without legal documentation but later becoming a citizen. A bivocational social worker before she retired to work full time in ministry, she has long assisted migrants from Nicaragua and political asylum-seekers.

Valiente’s faith calls her “ to help the most vulnerable and those that don’t have a voice,” she said. Every other Thursday, her women’s group members go to the detention center, where they sometimes are a detained immigrant’s first visitors in six months. “We all cry with them,” she said.

While many detained immigrants find strength in each other or in Bible study, many of those she visits are on psychotropic medications because of depression, anxiety or an inability to sleep, said Valiente. They’ll have limited access to Christmas services because there is only one chaplain for three detention centers, and while pastors like the Valientes can visit, they cannot hold services.

In the weeks before Christmas, even as the Valientes’ congregations prepare for the holiday, Ada Valiente is trying to talk one detained and demoralized man out of signing his deportation papers, while meeting with his wife to make a plan. For a mother who has received an eviction notice since her husband has been detained, Valiente is trying to secure rental assistance. (The woman, Valiente said, may receive a deportation order herself any minute.)

Telling her congregation about the work a few weeks ago, Valiente couldn’t hold back tears. “As normal as it is, you get a little bit with the blues at Christmas,” she said.

Olga said her 10-year-old son, Kevin, a U.S. citizen, told her, “I don’t want to spend Christmas or New Year’s without my dad,” and she has had to tell him, “It’s not in my hands.” Kevin also worries about his mom. When she was late coming home one night, he was sobbing, thinking she too had been detained, Olga said.

One Nicaraguan woman who asked to remain anonymous said she struggles to afford the per-minute charges to talk with her husband on a detention phone. They limit themselves to brief exchanges a couple of times a day, when he asks whether she’s taken her medication or whether she’s eaten her lunch.

When she spoke with RNS in October, she was sleeping in their twin bed holding his pajamas and spending her days beside the giant teddy bear he bought her. In the months since then, she’s had to leave the apartment, sell many of their things and find a job.

On the night Melanie’s husband was detained, one of the twins spent the night with a fever because, she said, he had spent too much time on the sidewalk in the sun when his mother was stranded. She and another mother requesting anonymity said their small children had lost weight since their fathers were detained.

Melanie’s toddler also struggled to sleep, she said: “ The day they detained him, all they gave me was a little plastic bag with his necklace and his watch, so she would just carry it around the house and be like, ‘Papa, Papa.’”

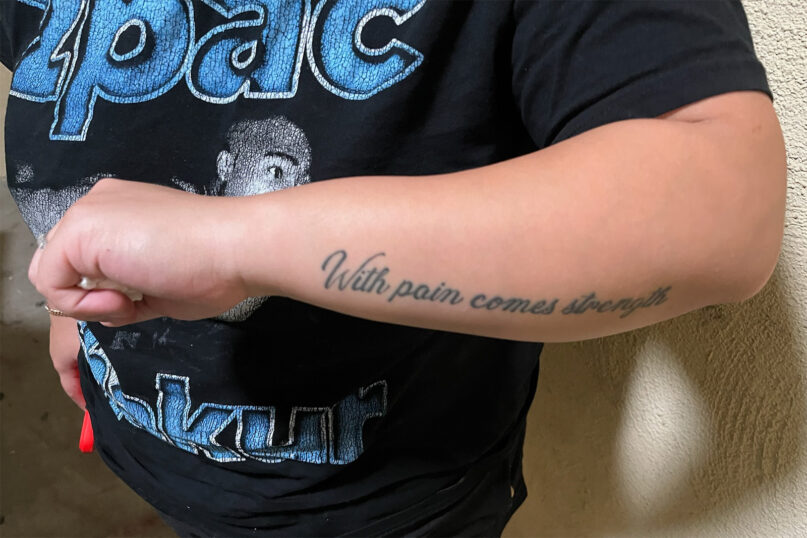

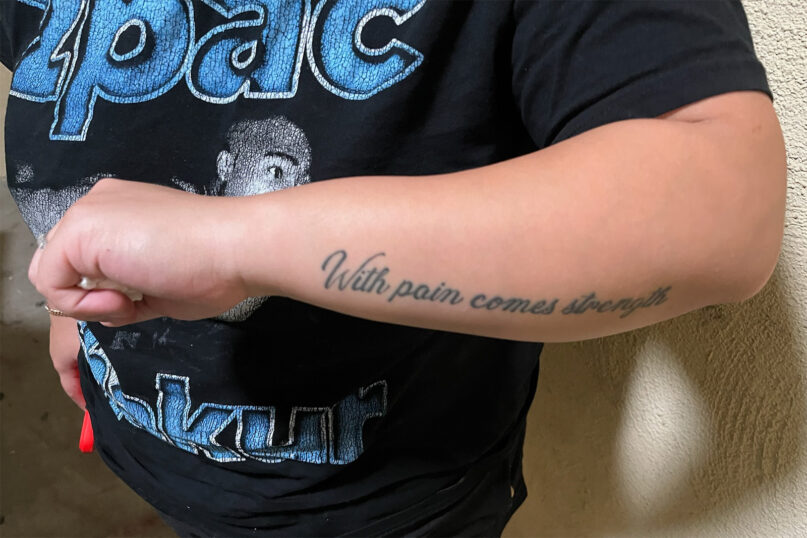

Melanie’s tattoo reading “With pain comes strength.” (RNS photo/Aleja Hertzler-McCain)

All four women told RNS they lean on their faith, trusting in God to give them strength.

The Nicaraguan mother who fled with her kids said in Spanish that she told her son: “My love, if you want to be with your dad, we have to kneel down every day, because only God can help us. God can touch the heart of the president so that he stops doing these things.”

She added: “We pray for the president, we pray for the immigration officials to understand that what they’re doing is not right because they’re hurting our family.”

Just a week before Christmas Eve, or “Nochebuena” for Latino Christians, Olga’s Guatemalan husband folded to the pressure to sign his own deportation papers, despite Carlos Rincón’s warnings.

“He was putting on a lot of stress and he was threatened, saying that if you don’t sign, we will deport you anyway, and we’re gonna make it harder for you, or if you don’t sign, you will stay for years here, detained,” said the pastor.

And the same day, Melanie’s husband’s bond was denied, with no hearing in sight until April.

“That’s my job, I guess — right now, trying to be with people that are receiving very bad news,” Rincón said.

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — As Los Angeles pastors lead congregations and preach about the meaning of Christmas, they’re facing the emotional devastation of families struggling to cling to hope.

A Christmas Nativity scene portrayed as a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center sits on display in front of the Oak Lawn United Methodist Church, in Dallas, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

Aleja Hertzler-McCain

December 23, 2025

RNS

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Nine days before Christmas, a group of clergy huddled around a young mother outside the Los Angeles Federal Building, praying for a Christmas miracle that a judge would set bond for her husband at a hearing the following day and release him from immigration detention.

Melanie, 21, who agreed to speak to RNS on the condition that only her first name be used, has been nursing a hope for months that her husband, an immigrant from Nicaragua, would be back home in time to celebrate their infant twins’ first Christmas.

In July, as her husband prepared for an Immigration and Customs Enforcement check-in at the federal building, Melanie was confident he would be spared detention because, she told him, “we’ve been doing things right.” Leaving nothing to chance, she decided the family would go to the check-in together. Surely, she thought, they wouldn’t detain him in front of his wife, a U.S. citizen, and three kids.

But after her husband had filled out forms and answered agents’ questions about his tattoos, he was taken into a separate room. After 15 minutes, “ all of a sudden, I hear him screaming my name,” Melanie recalled.

Running to him, she saw he had been handcuffed. “ I felt like the whole world just fell on top of me,” she said. With her kids watching, the agents “cornered” her, not letting her approach her husband or say goodbye, but she said, “ I could just tell in his face that he was scared.”

Within five minutes, she was escorted out into the hot July sun. Without their father, there weren’t enough hands to carry the twins’ car seats and her toddler daughter.

The Revs. Carlos and Amparo Rincón post a video to social media from the Metropolitan Detention Center in Los Angeles. (Video screen grab)

It was there, stranded on the sidewalk, that Melanie met the Revs. Amparo and Carlos Rincón, married Pentecostal pastors who belong to a network of Los Angeles faith leaders who are supporting families broken apart by the Trump administration’s mass deportation policies.

“She looked younger than my daughter,” said Carlos. His wife approached the crying mother, whose eldest was inconsolable after what she had witnessed. The Rincóns have since helped Melanie with diapers, baby formula and groceries, in addition to praying for her and offering to pay her 25-year-old husband’s bond through Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, colloquially known as CLUE.

Amparo and other women lead an interfaith group with CLUE that meets every Tuesday to march in prayer around the federal building, a center for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The group calls itself the Godmothers of the Disappeared.

Melanie’s family is just one of many the pastors have found on their weekly visits. Carlos Rincón said his church, which he asked not be named out of fear of retaliation, is supporting about 25 families. One woman, a wife separated from her detained husband, texted RNS in Spanish: “There is no Christmas for separated families.”

Carlos and another group of pastors with his organization Matthew 25, alongside CLUE, plan to break away from their other pastoral responsibilities on Christmas Eve to hold a vigil outside the downtown ICE center, preaching one of his central messages that “ God himself experienced what immigrants experience.”

Detainees at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Eloy Detention Facility in Eloy, AZ. (Photo by Charles Reed/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, File)

Even so, he acknowledges, “it is hard.” He said, “ there are too many needs and too many people in so many difficult situations.”

As Advent came and the Rincóns preached about the meaning of Christmas, they faced the emotional devastation of families struggling to cling to hope. It wasn’t until Dec. 1, when Olga, a worship team leader, learned her husband had been detained, that the detentions affected the church directly.

Since then, Olga wakes up too depressed to sing. She’s having trouble eating and sleeping. Despite that, she said in Spanish, “I try to go (to church) because I know God is the one who gives me the strength to continue. He is the one who is with me every day.”

But still, Olga said, “because of what we’re living through, I don’t have a head to think. It doesn’t feel like it’s Christmastime.”

The Revs. Melvin and Ada Valiente. (Courtesy photo)

The Rev. Ada Valiente, who supports at least 30 separated families with her husband, Melvin, through their We Care ministry, said that several mothers are suffering a mental health crisis. Struggling to make practical plans to address their immediate needs and unable to plan for their future, they have little time to think about celebrating Christmas.

The Valientes, who lead two American Baptist Churches USA congregations in Los Angeles County, hear about families in need of support from other pastors, other immigrants in the detention centers or sometimes the families themselves.

While the couple will offer advice and recommend reliable immigration attorneys to anyone who reaches out, they prioritize the people with the highest needs — detainees with no family, or whose family cannot visit them because they lack legal status themselves or lack resources. Holistic support provided may include prayer, financial assistance or visits to detained and separated family members.

Melanie and an immigrant mother under the Valientes’ care who requested anonymity because she lacks legal status both said they had been charged thousands of dollars by immigration attorneys who made no effort to help the detained men.

In the months since Melanie’s husband was detained, she has managed to finish his active construction contracts. She had to give up their first apartment and move back in with her mother, who helps with the kids. Melanie also followed the legal details of her husband’s case until she found a new attorney, who was willing to sleep in the detention center’s lobby in order to see her husband.

Melanie met her husband in 2022, when her Nicaraguan mother threw a birthday party for the newly arrived fellow Nicaraguan, who had crossed into the United States legally via the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s CBP One app. He was granted parole while seeking political asylum.

She said her husband is requesting asylum based on his claim that he was wrongly incarcerated in Nicaragua for two years before being pardoned. “He was just at the wrong place at the wrong time,” she said. He’d already applied to be a permanent U.S. resident before he was detained in LA.

‘We are the life of the church right now’: Bishop Chau talks Latino Catholics, inclusion

Several of the other women receiving help from the Rincóns and Valientes also fled the human rights crisis of Nicaragua, where co-Presidents Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, have decimated civil society, including religious institutions, and instituted authoritarian rule. One woman told RNS her detained husband had been arrested, beaten and threatened with worse after participating in a march. They fled Nicaragua, leaving their children behind with relatives. When her husband was detained in the U.S., he was still in need of medical care for injuries from his beating.

Another woman told RNS that she and her now-detained partner refused to join the Ortegas’ socialist Sandinista Party because of their Christian faith, despite threats of physical harm to them and their son. Unless they joined, they were told, they would not be protected by the police. Twice, her husband was detained without cause in Nicaragua, she said.

Both women asked for anonymity because they fear deportation.

Ada Valiente, whose brother was a political prisoner of Nicaragua’s conservative Somoza dictatorship, fled with her family to the U.S. when she was a child, arriving without legal documentation but later becoming a citizen. A bivocational social worker before she retired to work full time in ministry, she has long assisted migrants from Nicaragua and political asylum-seekers.

Valiente’s faith calls her “ to help the most vulnerable and those that don’t have a voice,” she said. Every other Thursday, her women’s group members go to the detention center, where they sometimes are a detained immigrant’s first visitors in six months. “We all cry with them,” she said.

While many detained immigrants find strength in each other or in Bible study, many of those she visits are on psychotropic medications because of depression, anxiety or an inability to sleep, said Valiente. They’ll have limited access to Christmas services because there is only one chaplain for three detention centers, and while pastors like the Valientes can visit, they cannot hold services.

In the weeks before Christmas, even as the Valientes’ congregations prepare for the holiday, Ada Valiente is trying to talk one detained and demoralized man out of signing his deportation papers, while meeting with his wife to make a plan. For a mother who has received an eviction notice since her husband has been detained, Valiente is trying to secure rental assistance. (The woman, Valiente said, may receive a deportation order herself any minute.)

Telling her congregation about the work a few weeks ago, Valiente couldn’t hold back tears. “As normal as it is, you get a little bit with the blues at Christmas,” she said.

Olga said her 10-year-old son, Kevin, a U.S. citizen, told her, “I don’t want to spend Christmas or New Year’s without my dad,” and she has had to tell him, “It’s not in my hands.” Kevin also worries about his mom. When she was late coming home one night, he was sobbing, thinking she too had been detained, Olga said.

One Nicaraguan woman who asked to remain anonymous said she struggles to afford the per-minute charges to talk with her husband on a detention phone. They limit themselves to brief exchanges a couple of times a day, when he asks whether she’s taken her medication or whether she’s eaten her lunch.

When she spoke with RNS in October, she was sleeping in their twin bed holding his pajamas and spending her days beside the giant teddy bear he bought her. In the months since then, she’s had to leave the apartment, sell many of their things and find a job.

On the night Melanie’s husband was detained, one of the twins spent the night with a fever because, she said, he had spent too much time on the sidewalk in the sun when his mother was stranded. She and another mother requesting anonymity said their small children had lost weight since their fathers were detained.

Melanie’s toddler also struggled to sleep, she said: “ The day they detained him, all they gave me was a little plastic bag with his necklace and his watch, so she would just carry it around the house and be like, ‘Papa, Papa.’”

Melanie’s tattoo reading “With pain comes strength.” (RNS photo/Aleja Hertzler-McCain)

Latino pastors look to refit preaching and pastoral care to trauma of mass deportations

All four women told RNS they lean on their faith, trusting in God to give them strength.

The Nicaraguan mother who fled with her kids said in Spanish that she told her son: “My love, if you want to be with your dad, we have to kneel down every day, because only God can help us. God can touch the heart of the president so that he stops doing these things.”

She added: “We pray for the president, we pray for the immigration officials to understand that what they’re doing is not right because they’re hurting our family.”

Just a week before Christmas Eve, or “Nochebuena” for Latino Christians, Olga’s Guatemalan husband folded to the pressure to sign his own deportation papers, despite Carlos Rincón’s warnings.

“He was putting on a lot of stress and he was threatened, saying that if you don’t sign, we will deport you anyway, and we’re gonna make it harder for you, or if you don’t sign, you will stay for years here, detained,” said the pastor.

And the same day, Melanie’s husband’s bond was denied, with no hearing in sight until April.

“That’s my job, I guess — right now, trying to be with people that are receiving very bad news,” Rincón said.

(RNS) — Clergy, churches and other religious organizations wrestle with how to mark one of the most important Christian holidays while also serving an immigrant population in crisis.

Bishop Brendan Cahill, bishop of the Diocese of Victoria in Texas, preaches to migrants during an Advent service at the Del Camino Jesuit Border Ministries Casa del Migrante, Nov. 30, 2025, in Brownsville, Texas. (Photo courtesy of the Rev. Brian Strassburger)

Jack Jenkins and Aleja Hertzler-McCain

December 24, 2025

RNS

(RNS) — Earlier this month, the Rev. Pilar Pérez, a United Methodist minister in the denomination’s Western North Carolina Conference, called up a parishioner who hadn’t been to worship in a while. The pastor encouraged the congregant to attend Christmas services, even offering to give her a ride.

“I was begging her: ‘I’ll go and pick you up,’” Pérez said.

The parishioner could not be convinced. She told Pérez that come Christmas, her family planned to mark the Christian holiday the safest way they know how: by watching the service on Facebook Live.

Pérez understood. Like many immigrant families, the family members have barely left their home in recent weeks out of fear of encountering federal immigration agents. It’s a fear they believe is well founded, as immigration officers have detained and deported thousands across the country, including at least one person in North Carolina who was just outside a church.

The Rev. Pilar Pérez. (Photo courtesy of WNCCUMC)

“That’s where they are,” said Pérez, who has spent recent months delivering groceries and other necessities to such families.

Faith leaders are facing similar situations across the country this Christmas season, as clergy, churches and other religious organizations wrestle with how to mark one of the most important Christian holidays while also serving an immigrant population in crisis.

The Rev. Melvin Valiente, who pastors two Los Angeles County Baptist churches with his wife, Ada, said he is preaching a specific message to his congregations this holiday season: “Jesus knows what it is to be an immigrant, knows what it is to be persecuted.”

He also uses a system that sends out personalized texts with Bible verses, hoping Christmas messages of peace can connect with members who are too afraid to come to church.

Their church members will also be preparing bags of food for families outside their congregation who have a detained loved one or are too afraid to go out, both to fortify them with regular groceries and help them celebrate a special dinner for “Nochebuena,” or Christmas Eve. One church member plans to host lonely immigrants at her own Nochebuena dinner.

RELATED: ‘There is no Christmas for separated families’: Pastors tend to immigrant families in crisis

Back in North Carolina, attendance at Pérez’s majority-immigrant church has dropped as much as 40% since November, she said, when a surge of immigration agents deployed to her state for a week. In her congregation, 11 families essentially haven’t left their homes since.

The pastor compared the situation to the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when churches avoided meeting in person and moved worship services online.

“Isolation is hurtful — it’s hurtful spiritually, emotionally and physically,” Pérez said.

In response, Pérez’s church has partnered with another nearby Methodist congregation to offer an additional layer of protection for churchgoers. Over the past few weeks, the pastor of a nearby partner congregation has come to the church and sat near the door during worship — and plans to do so during Christmas services as well. The idea, Pérez says, is for the partner pastor to be the first person immigration enforcement officers encounter should they ever approach the church.

People protest against federal immigration enforcement, Nov. 15, 2025, in Charlotte, N.C. (AP Photo/Erik Verduzco)

Pérez and others have also delivered weekly food boxes to congregants who are still staying home, an effort bolstered by an influx of donations: A local Christmas giving ministry shifted its efforts to the nearby immigrant population, with 80% of donations heading to Hispanic families.

The Rev. Luke Edwards oversees a separate fund set up by the Western North Carolina Conference after the Charlotte raids for the needs of immigrant congregations, such as legal costs and rent.

But even with the influx of resources, Edwards said, communities are struggling. He noted that many of the Hispanic churches he works with traditionally celebrate Las Posadas, reenactments of the Christmas story, in December.

But this year, “They’re either canceling those, scaling them back, rescheduling them or moving things onto Zoom,” he said. The federal government’s mass deportation effort, Edwards said, “is impacting our churches’ ability to worship.”

In Boston, Bishop Nicolas Homicil said his largely Haitian flagship church, Voice of the Gospel Tabernacle Church, still plans to have in-person worship on Christmas, but it’s expecting lighter attendance than the up-to-300 it typically draws.

The Trump administration is slated to revoke Temporary Protected Status for Haitians on Feb. 3.

“We don’t want to fool ourselves to say, ‘Yes, we expect the church to be full,’ because there are people who are still afraid to come out,” Homicil said. “People are even afraid to come to (the) food pantry.”

He added of other Boston churches: “Every church is suffering this crisis.”

Other clergy are seeking to bring the holidays to immigrants who have already been separated from their communities. The Rev. Brian Strassburger, a Jesuit priest who works along the U.S.-Mexico border as director of Del Camino Jesuit Border Ministries, said he plans to host a Posada event outside the airport in Harlingen, Texas.

“During that span of time, we anticipate that there will be one, two or even three flights coming in and out with detained migrants,” Strassburger said. He hopes the sight of Mary and Joseph seeking shelter will offer a “public witness there in that space” and be “a sign of hope.”

The priest said his group of three Jesuits is supporting migrants who are fighting “hopelessness and despair” during Christmas. They were unable to get permission to celebrate a Christmas Mass at Port Isabel Detention Center, but they were able to celebrate several Advent Masses there, as well as host more-typical Posadas with skits and piñatas for the children in two Reynosa, Mexico, migrant shelters.

The Rev. Brian Strassburger. (Courtesy photo)

They are also planning to celebrate 10 baptisms and two first Communions on Christmas Eve in a migrant shelter in Matamoros, Mexico. The immigrants living in those shelters are in many ways stuck, lacking the means to go elsewhere in Mexico or back home and no longer able to seek U.S. asylum after President Donald Trump suspended that program in January.

Strassburger described a recent experience of holding a 2-day-old baby in the shelter and being struck by the parallels in the Christmas story.

“Standing in a forgotten, underresourced migrant shelter along the U.S.-Mexico border on the wrong side of a political boundary is much like this stable in Bethlehem because there’s no room at the inn and that’s where Christ enters into the world,” he said.

With the arrival of Christmas — a gift-giving season — religious leaders have been trying to offer what support they can.

In Washington, D.C.’s Maryland suburbs, the English-speaking community at St. Camillus Catholic Church joined Latinos for their Las Posadas celebrations this month to show “we see us as one family” and make Latinos feel less afraid to participate, said Kathy, a coordinator of the parish’s migrant response team who asked to be identified by her first name to avoid harassment.

Since the fall, their parish has averaged more than one new family a week experiencing a detention, she said.

“To be honest, I wish that we had time and energy for some special Christmas gift programs, but the truth is we are running as fast as we can and using all of the resources we have just to kind of keep up with the day-to-day emergency needs,” Kathy said, including prayer, emergency counseling and food deliveries. They also try to have a supportive presence outside immigration court.

Federico, a Catholic leader in Chicago who asked to use his middle name because he lacks legal immigration status, said his parish is facing the same deluge. He is pleading for more wealthy congregations to step in because of the sheer scale of the needs.

In North Carolina, a Charlotte-area initiative called Operación Esperanza has emerged as a partnership between Transforming Nations Ford, a community development nonprofit, and Iglesia Tabernaculo de Gracia, a Hispanic Pentecostal church

The project has been distributing food and other items to impacted immigrant families, but according to Rosa Ramirez, who helps lead the effort, volunteers recently began asking families what their children would want for Christmas. The effort has been difficult — partly, she said, because asking for something “is, culturally, not comfortable for a lot of our families.”

But beyond that, “for a lot of our families, it’s not even about trying to figure out the holidays,” Ramirez said. “That’s just the last thing on their mind right now.”

Yet she said the holiday effort is an important part of their work — especially for families who may be celebrating Christmas alone or, in some cases, without family members who have been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“It’s super important that they have choice — that our children get to consider what they would want on their Christmas list, even if that’s not something that they’ve done before or that they thought they were going to be able to do this year,” Ramirez said.

And besides, Ramirez said, the shared faith of those involved in the effort — which includes an array of local churches — points them toward an unambiguous conclusion.

“As Christians, we’re called to love our neighbor and to treat the immigrant and the foreigner as our own,” she said. “I think I’ve really seen that lived out in a way that is really beautiful to see, even though it’s such a horrifying time.”

Yoga, meditation classes taught in Spanish offer healing to stressed communities

(RNS) — ‘Our community is definitely experiencing heightened levels of stress, insecurity, uncertainty, anxiety and fear,’ said Xiomara Arauz, a Denver-based yoga and meditation teacher. ‘If the class is in Spanish and everybody speaks Spanish, people feel more safe being in that environment, feeling like they’re understood or they're accepted here.’

People participate in a class at Yogiando NYC in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood in New York. (Photo courtesy of Rosana Rodriguez)

Richa Karmarkar

December 23, 2025

Rosana Rodriguez, left, and Marisol Alvarez.

(RNS) — ‘Our community is definitely experiencing heightened levels of stress, insecurity, uncertainty, anxiety and fear,’ said Xiomara Arauz, a Denver-based yoga and meditation teacher. ‘If the class is in Spanish and everybody speaks Spanish, people feel more safe being in that environment, feeling like they’re understood or they're accepted here.’

People participate in a class at Yogiando NYC in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood in New York. (Photo courtesy of Rosana Rodriguez)

Richa Karmarkar

December 23, 2025

RNS

(RNS) — At the New York City yoga studios she frequented in the 2010s, Rosana Rodriguez sometimes found herself the only Latina in the room. “I felt really intimidated,” said the 58-year-old native New Yorker. Predominantly white studios and expensive monthly fees gave her and others in her community the impression that wellness spaces “weren’t for them.”

But the practice of yoga itself, Rodriguez said, saved her life. It was a consistent stress-reduction technique after an abusive relationship and losing her job.

During yoga nidra — or guided meditation in the Savasana posture, often at the end of class — Rodriguez caught herself translating what her teacher said into Spanish, sparking a “revelation.” “I wanted to bring this level of healing to my community,” she said.

Rodriguez soon founded Yogiando NYC, the first Spanish-English bilingual studio in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, which has a majority Hispanic population. Offering weekly $10 yin yoga classes at Yogiando, which is a made-up word to mean “doing yoga,” since 2017, Rodriguez said the space became a hub of solace where Spanish-speakers could share their anxieties about anything from immigration to family to their jobs with one another.

“One of the things that I have prided myself in creating for this community is a safe space,” she said. “The closing meditation is that I’m saying to them, ‘You are held and protected.’ I’m teaching them how to be aware, how to listen to their body, how to breathe. Many of these women have told me, ‘I do these breathing exercises every day, and they’ve helped me.’ They’ve told me how yoga has changed their life.”

As Yogiando NYC has done, increasing language accessibility in spiritual wellness spaces across the country has opened up meditation and yoga to more diverse American populations. For Spanish-speaking practitioners like Rodriguez, offering these kinds of classes is crucial to the spiritual-wellness movement in being able to respond to growing mental health concerns as anti-immigrant sentiments and federal actions surge in a country where Spanish is the second-most-spoken language.

RELATED: In new book, yoga teacher Harpinder Kaur Mann seeks to reclaim the practice’s spiritual roots

Xiomara Arauz, originally from Panama, teaches meditation and yoga in Spanish in Denver through the Art of Living, a global humanitarian organization founded by Indian guru Sri Sri Ravi Shankar. Arauz and a handful of other instructors across the country have also taught online and in-person Spanish instruction of the Sudarshan Kriya, or SKY breathing technique, to hundreds since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our community is definitely experiencing heightened levels of stress, insecurity, uncertainty, anxiety and fear,” Arauz told RNS. “If the class is in Spanish and everybody speaks Spanish, people feel more safe being in that environment, feeling like they’re understood or they’re accepted here. They feel a lot better when they leave through the doors of the yoga studio than when they came in.”

Particularly in meditative practices, Arauz said, it is “a different kind of comfort” to practice in one’s native tongue, as the work “is more internal, more subtle.” And her “warm and friendly” personality is able to “come alive” as an instructor in Spanish.

“There is a nuance that I think makes a difference when you are going into these deeper states of relaxation and your conscious mind is not trying to translate,” she said. “There is no resistance in the mind to be doing something else other than absorbing it. They’re able to relax a lot more, be more there, be more present.”

(RNS) — At the New York City yoga studios she frequented in the 2010s, Rosana Rodriguez sometimes found herself the only Latina in the room. “I felt really intimidated,” said the 58-year-old native New Yorker. Predominantly white studios and expensive monthly fees gave her and others in her community the impression that wellness spaces “weren’t for them.”

But the practice of yoga itself, Rodriguez said, saved her life. It was a consistent stress-reduction technique after an abusive relationship and losing her job.

During yoga nidra — or guided meditation in the Savasana posture, often at the end of class — Rodriguez caught herself translating what her teacher said into Spanish, sparking a “revelation.” “I wanted to bring this level of healing to my community,” she said.

Rodriguez soon founded Yogiando NYC, the first Spanish-English bilingual studio in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, which has a majority Hispanic population. Offering weekly $10 yin yoga classes at Yogiando, which is a made-up word to mean “doing yoga,” since 2017, Rodriguez said the space became a hub of solace where Spanish-speakers could share their anxieties about anything from immigration to family to their jobs with one another.

“One of the things that I have prided myself in creating for this community is a safe space,” she said. “The closing meditation is that I’m saying to them, ‘You are held and protected.’ I’m teaching them how to be aware, how to listen to their body, how to breathe. Many of these women have told me, ‘I do these breathing exercises every day, and they’ve helped me.’ They’ve told me how yoga has changed their life.”

As Yogiando NYC has done, increasing language accessibility in spiritual wellness spaces across the country has opened up meditation and yoga to more diverse American populations. For Spanish-speaking practitioners like Rodriguez, offering these kinds of classes is crucial to the spiritual-wellness movement in being able to respond to growing mental health concerns as anti-immigrant sentiments and federal actions surge in a country where Spanish is the second-most-spoken language.

RELATED: In new book, yoga teacher Harpinder Kaur Mann seeks to reclaim the practice’s spiritual roots

Xiomara Arauz, originally from Panama, teaches meditation and yoga in Spanish in Denver through the Art of Living, a global humanitarian organization founded by Indian guru Sri Sri Ravi Shankar. Arauz and a handful of other instructors across the country have also taught online and in-person Spanish instruction of the Sudarshan Kriya, or SKY breathing technique, to hundreds since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our community is definitely experiencing heightened levels of stress, insecurity, uncertainty, anxiety and fear,” Arauz told RNS. “If the class is in Spanish and everybody speaks Spanish, people feel more safe being in that environment, feeling like they’re understood or they’re accepted here. They feel a lot better when they leave through the doors of the yoga studio than when they came in.”

Particularly in meditative practices, Arauz said, it is “a different kind of comfort” to practice in one’s native tongue, as the work “is more internal, more subtle.” And her “warm and friendly” personality is able to “come alive” as an instructor in Spanish.

“There is a nuance that I think makes a difference when you are going into these deeper states of relaxation and your conscious mind is not trying to translate,” she said. “There is no resistance in the mind to be doing something else other than absorbing it. They’re able to relax a lot more, be more there, be more present.”

Rosana Rodriguez, left, and Marisol Alvarez.

(Photo courtesy of Rosana Rodriguez)

Diana Winston, a mindfulness teacher and director of UCLA Mindful — an education and research center that provides science-backed mindfulness instruction to schools, hospitals and corporate offices — said the center’s Mindful App offers instruction in 19 languages, including a separate Spanish-only feature for California’s large non-English-speaking population. She said the organization is committed to “radical accessibility” to remove language, economic and religious barriers from mindfulness practices.

“It’s a very scary time for a lot of people in this country,” she said. “I’m very worried about the most vulnerable populations, for people who are in some ways being targeted. And I feel like anything that can help support their mental health and well-being, since that’s what mindfulness really does, that would be a fantastic thing to be able to offer.

“And my secret wish,” she added, “the people who could really use mindfulness, who are making these horrible decisions, might transform themselves, too. What if somebody moved from a place of being stuck in seeing people as other, and hatred and violence, and began to meditate and had more compassion in their heart? That would be incredible.”

Still, barriers exist to getting Spanish speakers to the studios, sometimes based on an idea that yoga and meditation conflict with their Christian faith, practitioners said. Though the last few decades have seen a seismic growth of these Indian practices in secular contexts, often far removed from their Hindu and Buddhist religious roots, some still feel reluctant, said Rodriguez, who refrains from using Sanskrit terms, or the meditative sound “Om,” in her classes.

Marisol Alvarez, a 60-year-old student at Yogiando from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, said she has been told that she shouldn’t be doing yoga, despite the physical, mental and even spiritual benefits she found in the practice.

“They said, ‘The priests don’t want you to practice, it’s not of God,'” she told RNS in Spanish. “But I’m healing. God wants me to heal. It’s very big how [yoga] has helped me with my faith, connecting with the universe, with the divine higher power.”

Alvarez has brought her daughter, her mother and people she meets on the street into yoga classes. And the studio’s community of women — who have now traveled and shared their dreams with each other — is “filled with so much love,” she said.

“There are times that I’ve arrived at the class feeling like I couldn’t breathe,” she said. “But I breathed.”

Diana Winston, a mindfulness teacher and director of UCLA Mindful — an education and research center that provides science-backed mindfulness instruction to schools, hospitals and corporate offices — said the center’s Mindful App offers instruction in 19 languages, including a separate Spanish-only feature for California’s large non-English-speaking population. She said the organization is committed to “radical accessibility” to remove language, economic and religious barriers from mindfulness practices.

“It’s a very scary time for a lot of people in this country,” she said. “I’m very worried about the most vulnerable populations, for people who are in some ways being targeted. And I feel like anything that can help support their mental health and well-being, since that’s what mindfulness really does, that would be a fantastic thing to be able to offer.

“And my secret wish,” she added, “the people who could really use mindfulness, who are making these horrible decisions, might transform themselves, too. What if somebody moved from a place of being stuck in seeing people as other, and hatred and violence, and began to meditate and had more compassion in their heart? That would be incredible.”

Still, barriers exist to getting Spanish speakers to the studios, sometimes based on an idea that yoga and meditation conflict with their Christian faith, practitioners said. Though the last few decades have seen a seismic growth of these Indian practices in secular contexts, often far removed from their Hindu and Buddhist religious roots, some still feel reluctant, said Rodriguez, who refrains from using Sanskrit terms, or the meditative sound “Om,” in her classes.

Marisol Alvarez, a 60-year-old student at Yogiando from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, said she has been told that she shouldn’t be doing yoga, despite the physical, mental and even spiritual benefits she found in the practice.

“They said, ‘The priests don’t want you to practice, it’s not of God,'” she told RNS in Spanish. “But I’m healing. God wants me to heal. It’s very big how [yoga] has helped me with my faith, connecting with the universe, with the divine higher power.”

Alvarez has brought her daughter, her mother and people she meets on the street into yoga classes. And the studio’s community of women — who have now traveled and shared their dreams with each other — is “filled with so much love,” she said.

“There are times that I’ve arrived at the class feeling like I couldn’t breathe,” she said. “But I breathed.”

No comments:

Post a Comment