Also: Bringing a 400-million-year-old fossilized armored worm to virtual life.

JENNIFER OUELLETTE - 1/4/2022,

Enlarge

Lesley Cherns et al.

There's rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we're once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2020, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: How creating 3D virtual models can tell us more about ancient fossilized critters.

Researchers created a highly detailed 3D model of a 365-million-year-old ammonite fossil from the Jurassic period by combining advanced imaging techniques, revealing internal muscles that have never been previously observed, according to a paper published last month in the journal Geology. Another paper published last month in the journal Papers in Paleontology reported on the creation of 3D virtual models of the armored plates from fossilized skeletons of two new species of ancient worms, dating from 400 million years ago.

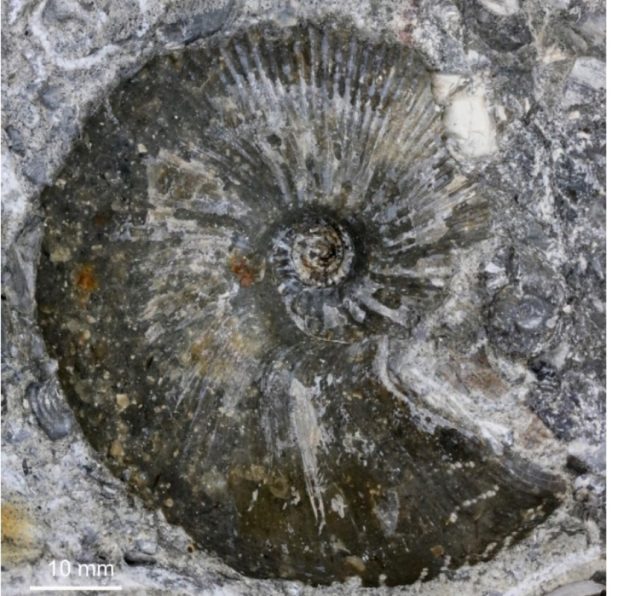

The ammonite fossil used in the Geology study was discovered in 1998 at the Claydon Pike pit site in Gloucestershire, England, which mostly comprises poorly cemented sands, sandstone, and limestone. Plenty of fragmented mollusk shells are scattered throughout the site, but this particular specimen was remarkably intact, showing no signs of prolonged exposure via scavenging, shell encrustation, or of being exhumed from elsewhere and redeposited. The fossil is currently housed at the National Museum Wales, Cardiff.

"When I found the fossil, I immediately knew it was something special," said co-author Neville Hollingworth, public engagement manager at the Science and Technology Facilities Council. "The shell split in two and the body of the fossil fell out revealing what looked like soft tissues. It is wonderful to finally know what these are through the use of state-of-the-art imaging techniques."

FURTHER READING Rare 50 million-year-old fossilized bug flashes its penis for posterity

First, the team photographed the internal mold and subjected the fossil to scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Then the researchers combined two powerful and complementary imaging techniques.

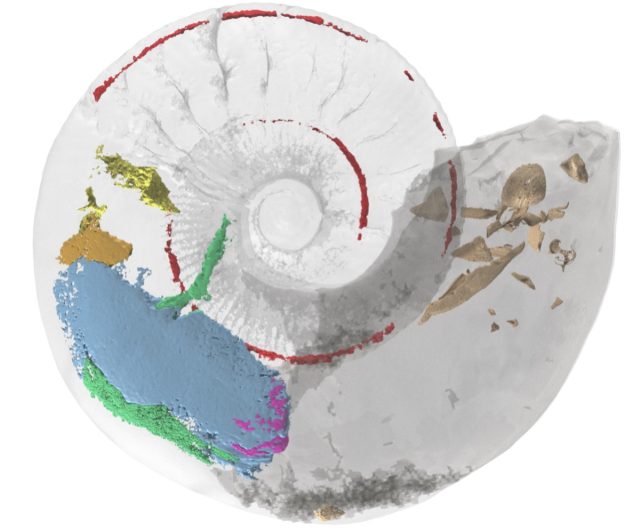

Neutron tomography is very similar to X-ray imaging methods, except it is not as sensitive to the density of materials. So some things easily visible with neutron imaging may be challenging or impossible to see with X-ray imaging (and vice versa). The team collected over 1,800 30-second projections via neutron tomography and used computer software to reconstruct them into 2D slices.

X-ray microtomography involves using X-rays to make cross-sections of a physical object that can be used to recreate a virtual 3D model without destroying the original object. With this method, the team captured 6,000 projections, which were reconstructed into a 3D image. The X-ray microtomography data is especially useful for revealing key details about the internal and external shell structure.Advertisement

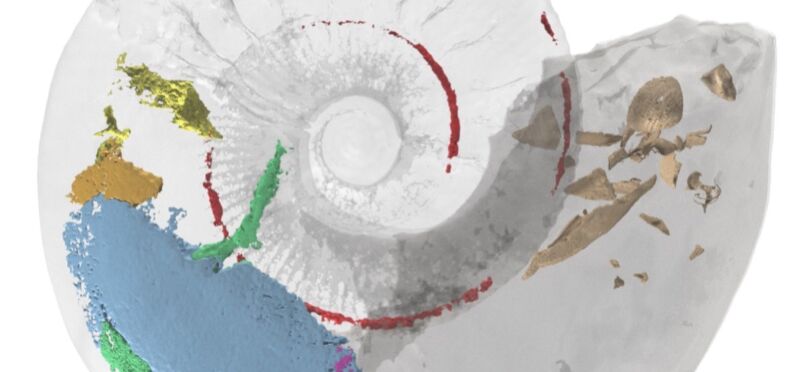

Both data sets were next imported into specialized software to create a combined 3D model. The X-ray data, when aligned with the neutron tomography data, resulted in remarkably detailed false-color 3D renderings of the fossil.

"Despite being discovered over 20 years ago, scientists have resisted the destructive option of cutting [the fossil] apart to see what's inside," said co-author Alan Spencer of Imperial College London. He continued:

Although this would have been much quicker, it risked permanent loss of some information. Instead, we waited until non-destructive technology caught up—as it now has. This allowed us to understand these interior structures without causing this unique and rare fossil any damage. This result is a testament to both the patience shown and the amazing ongoing technological advances in palaeontology.

Enlarge / Fossilized ammonite block.

Lesley Cherns et al., 2021

Paleontologists typically rely on the modern-day genus Nautilus as a model for ancient ammonoid fossils, which bears at least a superficial similarity to its Jurassic forebears. But this new 3D model showing the muscle and soft tissue suggests that those similarities may be only shell-deep, and ammonites might have more in common, evolutionarily speaking, with today's coleoid subgroup, which includes squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish.

Enlarge / 3D virtual model of a Jurassic-era ammonite fossil shows internal muscles never previously observed.

Lesley Cherns et al."Preservation of soft parts is exceptionally rare in ammonites, even in comparison to fossils of closely related animals like squid," said co-author Lesley Cherns of Cardiff University. "We found evidence for muscles that are not present in Nautilus, which provided important new insights into the anatomy and functional morphology of ammonites."

Most notably, this ammonite likely swam using jet propulsion, in which water is expelled through a tube or funnel (hyponome) located near the opening to the body chamber. Among other findings, the researchers observed paired muscles extending from the ammonite's body, which they surmise the animal likely used to retract itself further into its shell to avoid predators. (Ammonites didn't have defenses like an ink sac, common to octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish.)

"It has taken over 20 years of patient work and testing of new non-destructive fossil scanning techniques, until we hit upon a combination that could be used for this rare specimen," said co-author Russell Garwood of the University of Manchester, who is also a scientific associate at the Natural History Museum. "This highlights both: the importance of our national museum collections which permanently hold and give access to these important specimens; and the pace of technological advances within palaeontology over recent years."

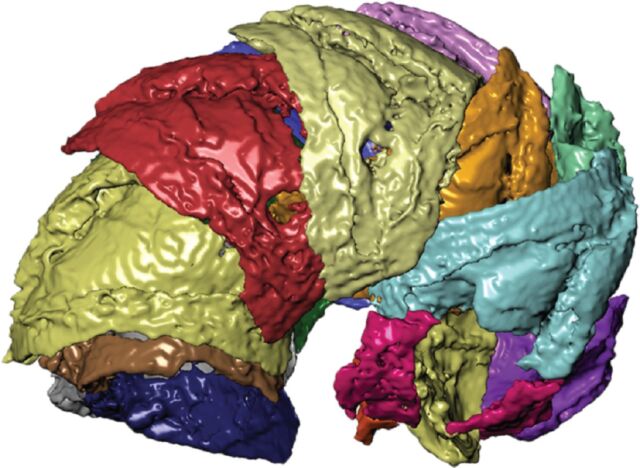

Enlarge / 3D virtual rendering: Right lateral view of segmented specimen of a 400-million-year-old armored worm.

S.M. Jacquet et al., 2021

Ancient armored worms

Moving from the Mesozoic to the Paleozoic era, scientists from the US and Australia discovered two new species of armored worms near Wellington Caves Reserve in New South Wales, Australia. The worms belong to a unique group of annelids called machaeridians. Lepidocoleus caliburnus is named after King Arthur's legendary sword, Excalibur, while Lepidocoleus shurikenus is so named because of its resemblance to shuriken, aka Japanese throwing stars.

This group of annelids is known for secreting interlocking calcitic plates (sclerites) of armor running the entire length of the animal. Yet even the best-preserved specimens have been difficult to study—until now. The team used another X-ray imaging technique known as micro-CT imaging to create the 3D virtual models for both new species, then virtually dissected the models to learn more about the structure and properties of the armored plates. The researchers also imaged 127 loose sclerites.

Enlarge / Fossilized specimen of the armored worm Lepidocoleus caliburnus, discovered in New South Wales, Australia.

S.M. Jacquet et al., 2021

"By using micro-CT, we can virtually separate the individual components of the armor," said co-author Sarah Jacquet, a paleontologist at the University of Missouri. "That allows us to see how it protected these worms until, unfortunately, they went extinct during one of the major extinction events in the fossil record. We are able to manipulate the virtual models to determine how the individual armor pieces moved relative to each other, as well as determine the degree of overlap between them."Advertisement

The analysis revealed that the unusual geometry of the plates may have improved resistance to predator attack. Specifically, the worms had two overlapping armor systems: one running down the length of the skeleton, and the other running down both sides. The researchers' next step will be to use the 3D virtual models to test how well the worms' armor may have protected the creatures from predator attacks and other stress factors.

The closest modern analog to these new species is the scale worm (which also has shield-like scales), but it's not a direct correlation. The armored worms may be an unrelated group that adapted similar features—an example of convergent evolution. "While this armor is a rather unique adaptation, and one that clearly does well for particular environments and protecting against particular predators, we do see other similar adaptations in a couple of unrelated animal groups, such as pangolins, pill bugs and millipedes," Jacquet said.

DOI: Geology, 2021. 10.1130/G49551.1</a >

DOI: Papers in Paleontology, 2021. 10.1002/spp2.1410 (About DOIs).

Listing image by Lesley Cherns et al.

No comments:

Post a Comment