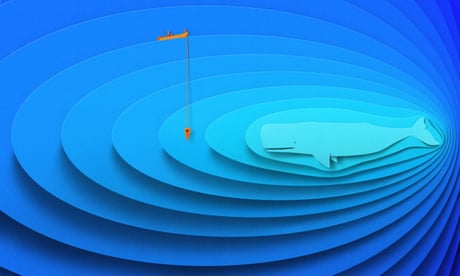

This part of the island is known as a ‘whale trap’ but using technology to prevent the events may interfere with the natural cycle

An arial view of some of almost 200 stranded whales that have died on

Tasmania’s Ocean Beach near Macquarie Harbour.

Photograph: Adam Reibel/AAP

Graham Readfearn

@readfearn

Graham Readfearn

@readfearn

THE GUARDIAN, AUSTRALIA

Sat 24 Sep 2022

A gruesome task remains for a rescue team responding to a mass stranding of pilot whales on Tasmania’s west coast – the gathering up and towing of about 200 huge carcasses out to the deep ocean.

That operation could take place on Sunday, after more than 30 of the whales – that are actually large oceanic dolphins – were successfully saved and taken back out to sea during three days of rescues this week.

The effort came almost two years to the day of Australia’s biggest cetacean stranding event involving 470 pilot whales at the same location.

So what might have caused this latest stranding, why is this place known as a “whale trap” and could anything be done about it – and should we even try?

Why is this part of Tasmania a whale-stranding hotspot?

Pilot whales are not well studied but are known to live in pods of 20 or 30 with females as leaders. Sometimes they form temporary “super pods” of up to 1,000 animals.

Tasmania is known to be a hotspot for strandings of cetaceans – whales and dolphins – and the area near Strahan’s Macquarie Harbour is particularly known for pilot whale strandings.

Prof Karen Stockin, an expert on cetacean strandings at Massey University in New Zealand, said nobody knows for sure why some become “whale traps” but it is likely to be a combination of prey, the shape of the coastline and the strength and speed of the tides.

“The tide comes in and out very quickly and you can get caught out,” she said. “If you’re a pilot whale foraging and are distracted, you can get caught. That’s why we refer to these places as whale traps.”

Whale strandings: what happens after they die and how do authorities safely dispose of them?

The deeper water where pilot whales live and feed – mostly on squid – is relatively close to the shore around Macquarie Harbour and the gradual sloping Ocean Beach could also be a natural hazard.

Dr Kris Carlyon, a wildlife biologist at the state’s marine conservation program, has been on the scene this week, as he was two years ago.

He said one theory was that the gentle sandy slope towards the shoreline could confuse the echolocation the pilot whales use to interpret their surroundings.

A gruesome task remains for a rescue team responding to a mass stranding of pilot whales on Tasmania’s west coast – the gathering up and towing of about 200 huge carcasses out to the deep ocean.

That operation could take place on Sunday, after more than 30 of the whales – that are actually large oceanic dolphins – were successfully saved and taken back out to sea during three days of rescues this week.

The effort came almost two years to the day of Australia’s biggest cetacean stranding event involving 470 pilot whales at the same location.

So what might have caused this latest stranding, why is this place known as a “whale trap” and could anything be done about it – and should we even try?

Why is this part of Tasmania a whale-stranding hotspot?

Pilot whales are not well studied but are known to live in pods of 20 or 30 with females as leaders. Sometimes they form temporary “super pods” of up to 1,000 animals.

Tasmania is known to be a hotspot for strandings of cetaceans – whales and dolphins – and the area near Strahan’s Macquarie Harbour is particularly known for pilot whale strandings.

Prof Karen Stockin, an expert on cetacean strandings at Massey University in New Zealand, said nobody knows for sure why some become “whale traps” but it is likely to be a combination of prey, the shape of the coastline and the strength and speed of the tides.

“The tide comes in and out very quickly and you can get caught out,” she said. “If you’re a pilot whale foraging and are distracted, you can get caught. That’s why we refer to these places as whale traps.”

Whale strandings: what happens after they die and how do authorities safely dispose of them?

The deeper water where pilot whales live and feed – mostly on squid – is relatively close to the shore around Macquarie Harbour and the gradual sloping Ocean Beach could also be a natural hazard.

Dr Kris Carlyon, a wildlife biologist at the state’s marine conservation program, has been on the scene this week, as he was two years ago.

He said one theory was that the gentle sandy slope towards the shoreline could confuse the echolocation the pilot whales use to interpret their surroundings.

What caused this stranding?

Scientists have carried out necropsies of some animals on the beach, and tissue samples and stomach contents are also being analysed.

Carlyon said these tests were to rule out any possible unnatural causes, but so far results were suggesting a natural event.

“We may never know the exact cause, but we are starting to rule things out,” he said.

Previous research of the stomach contents of pilot whales stranded on Ocean Beach found they were eating a variety of squid.

Carlyon said it’s possible the prey may have been closer to the shore, drawing one or two members of the pod into the natural whale trap.

Stockin said it would be very difficult to know what drew the whales too close. But whether they were chasing prey or simply took a wrong turn, the social structure of the pod would likely have drawn even more animals in.

“What ties pilot whales together is that they have strong social bonds that last almost a lifetime with other whales in their group,” she said. “It’s an incredibly strong bond and if you have one lost or debilitated animal, there’s a risk others will try to help.”

Pilot whales can communicate through clicks and whistles, and Stockin said this can make rescuing them more difficult, as those still on shore can continually call to pod mates for help, forcing them to return.

At some mass strandings, Stockin said, if a female that is the pod’s matriarch is still alive but stranded, junior pod members could continually return.

She said the fact that this stranding took place two years to the day after the previous major event could suggest a link to a seasonal or cyclical marine heatwave “but there’s just not enough analysis of these events”.

“We need to remember: mass strandings are a natural phenomenon, but that is not to say there are not times when strandings occur that are human induced,” she said.

Could anything be done to stop this happening again?

Carlyon said the state’s marine conservation program had considered potential approaches to prevent strandings in the future, including using underwater sound or developing an early warning system.

“It’s the million-dollar question: what can we do to stop this happening in the future given we know this is a mass stranding hotspot?” he said. I don’t have a good answer, to be honest.”

So far, Carlyon said, “there’s nothing leaping out at us as a feasible option” but the program would “continue to look if emerging technology or ideas could help”.

Talking to whales: can AI bridge the chasm between our consciousness and other animals?

Stockin said acoustic pingers are sometimes used to deter some dolphins.

“But there’s a very fine line here,” she said. “We would not want to scare animals away from critical foraging habitat.”

She said in some places around the world, underwater acoustic monitoring is used to alert authorities to times when marine mammals are in coastal waters.

“Then you might have a higher chance of responding,” Stockin said. “But in our desire as humans to want to fix things, we have to remember that sometimes things are just part of the natural cycle.”

In some indigenous cultures, whale strandings have traditionally been seen as a blessing from the sea. Dead cetaceans are also a food source for coastal and ocean wildlife.

But it was understandable, Stockin said, that humans felt an affinity to cetaceans and wanted to help them – regardless of what caused their stranding.

“They’re not just charismatic megafauna; they have a critical role to play in our oceans,” she said.

“They have dialects in the way we have accents. Some can even use tools – bottlenose dolphins use sponges on their [nose] to protect themselves when they’re foraging. They have strong social bonds. We know we are dealing with a female-led society here.

“They’re complex social mammals like us.”

No comments:

Post a Comment