The bell may be tolling for the longstanding Russian-Kazakh space programme following the launch of a “nanosatellite” jointly developed by Kazakhstan and China and launched into orbit by a Chinese rocket.

The launch of the Dier-5 spacecraft on December 13 placed the satellite into an orbit roughly 330 miles (531 kilometres) above earth, according to a Kazakh government statement. It took a team of specialists from Kazakhstan’s Al-Farabi University and Northeastern Polytechnical University in Xi’an, China, just a little over one year to develop the satellite, which will carry out scientific experiments, the statement added.

Kazakh officials touted the satellite as cost-effective and reliable for gathering and transmitting data.

“This collaborative work opens up new opportunities for space research, training qualified specialists, and developing joint satellites,” the government statement noted. “In addition, the project provides the possibility of remote sensing of Earth using a microsatellite.”

Not only did the launch mark a milestone for Kazakhstan’s space programme, it also gave a boost to Chinese efforts to capture a larger share of the commercial satellite launch market. The Dier 5 craft has a payload capacity estimated at about 660 lbs (299 kilograms).

Some observers see the Kazakh-Chinese initiative as a tacit vote of no-confidence in the more than two-decade-long Kazakh-Russian venture, dubbed Baiterek, to develop Kazakhstan’s space programme. Baiterek involves the adaptation of Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome to accommodate a new low-cost rocket design, the Soyuz-5.

The rocket, designed by Roscosmos, the Russian state space agency, has faced lengthy production delays. Originally intended to compete with SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in the commercial satellite launch market, some experts now wonder whether the Soyuz-5 will be effectively obsolete before one ever gets off the ground.

In October, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov gave an assurance that the Soyuz-5 was in its “final phase” of development. A month later, during a visit by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to Moscow, Russian officials indicated that a Soyuz-5 would be ready to launch before the end of year. With just days left in 2025, there is no sign of a launch taking place.

As part of the Tokayev visit, Kazakh and Russian officials signed a protocol intended to infuse fresh momentum into the Baiterek programme. But the Chinese launch makes it clear that Astana is hedging its bets.

Russia’s share of the launch market has steadily declined since the start of the 21st century. In 2005, Russia led the world with 26 orbital launches, commanding a near-50% share of the global total that year. A decade later, the overall number of launches increased dramatically around the world, while the number of Russian launches remained comparatively stagnant, resulting in a drop of its share of the market to 33%.

This year, Russia’s share has cratered to under 5% of 312 total launches. The United States now enjoys a 57% share of the market.

This article first appeared on Eurasianet here.

By AFP

December 17, 2025

Europe's Ariane 6 rocket carrying two Galileo navigation satellites launches from Kourou, French Guiana - Copyright AFP Ronan LIETAR

Florian Royer

Europe’s new Ariane 6 rocket successfully placed two satellites into orbit to join the EU’s rival to the GPS navigation system on Wednesday after the mission blasted off from French Guiana.

It was the fourth commercial mission of the Ariane 6 launch system since the long-delayed single-use rockets came into service last year.

The rocket launched into cloudy skies from Europe’s spaceport in Kourou on the northeastern coast of South America at 2:01 am local time (0501 GMT).

It was carrying two more satellites of the European Union’s Galileo programme, a global navigation satellite system that aims to make the bloc less dependent on the US’s Global Positioning System (GPS).

Applause rang out at the spaceport minutes before 7:00 am local time (1000 GMT) as it was confirmed that the satellites had been successfully deployed into orbit 23, 000 kilometres (14,000 miles) above Earth’s surface.

They will bring to 34 the number of Galileo satellites in orbit.

This addition will also “improve the robustness of the Galileo system by adding spares to the constellation to guarantee the system can provide 24/7 navigation to billions of users”, according to the European Space Agency (ESA) which oversees the programme.

According to the EU, Galileo is four times more accurate than GPS, providing navigation accuracy of up to one metre.

The “successful” launch also reinforces “Europe’s resilience and autonomy in space”, the ESA said on X.

– Reusable rockets wanted –

Previous Galileo satellites were primarily launched by Ariane 5 and Russian Soyuz rockets from Kourou.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe halted space cooperation with Moscow.

The loss of Russia’s Soyuz rockets — and repeated delays to Ariane 6 — left Europe without an independent way to blast missions into space for several months.

Before Ariane 6’s first commercial flight in March this year, the ESA resorted to contracting billionaire Elon Musk’s SpaceX to launch two Galileo satellites in September 2024.

Ariane 6 also blasted a weather satellite into orbit in August followed by a satellite for the EU’s observation programme Copernicus last month.

Arianespace, the operator of the rocket system, in September reduced by one the number of commercial launches on Ariane 6 this year, vowing to roughly double its number of missions in 2026.

The next mission, planned for the first quarter of 2026, will be the first to use a four-booster version of Ariane 6, rather than the current two.

It is scheduled to launch 34 satellites for the constellation of billionaire Jeff Bezos’s Amazon. The constellation, formerly known as Project Kuiper, was recently renamed Amazon Leo.

SpaceX has risen to dominate the booming commercial launch industry by developing rockets that are reusable — which Ariane 6 is not.

“We have to really catch up and make sure that we come to the market with a reusable launcher relatively fast,” ESA director Josef Aschbacher told AFP in October.

Several European aerospace firms are now bidding to develop the system for the ESA.

Copyright NASA

By Euronews with AP

Published on 17/12/2025

"There is strong justification for continued optimism regarding the potential for extraterrestrial life," said one of the study's authors.

New research suggests Saturn's largest moon contains slushy ice layers rather than a vast liquid sea, according to NASA.

It calls into question a decade-old theory about a hidden ocean beneath the surface of Saturn's moon Titan.

Instead of a vast underground ocean, Titan may contain deep layers of ice and slush similar to Arctic sea ice or aquifers, according to a study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature. The finding suggests pockets of liquid water could exist within these layers—environments where life might potentially survive.

Researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory reexamined data collected years ago by the Cassini spacecraft and reached conclusions that contradict the widely accepted ocean theory.

"Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we're probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers, which has implications for what type of life we might find, but also the availability of nutrients, energy and so on," said Baptiste Journaux, a University of Washington assistant professor who co-authored the study.

Journaux noted that any life forms would likely be microscopic, adding that "nature has repeatedly demonstrated far greater creativity than the most imaginative scientists".

No signs of life have been detected on Titan, which spans 3,200 miles and ranks as the solar system's second-largest moon. Shrouded by a hazy atmosphere, Titan is the only world apart from Earth known to have liquid on its surface, though at temperatures around -297 degrees Fahrenheit, that liquid is methane, not water, forming lakes and falling as rain.

While the absence of a full ocean might seem like a setback for the search for life, researchers say it actually broadens the possibilities. "It expands the range of environments we might consider habitable," said Ula Jones, a UW graduate student in Journaux's lab who worked on the study.

The researchers found that pockets of freshwater on Titan could reach temperatures of 21 degrees Celsius.

Nutrients would be more concentrated in these small water pools, potentially creating richer conditions for life than a diluted ocean would provide. If life exists on Titan, it may resemble polar ecosystems on Earth.

A Dynamic Interior

Lead author Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral fellow at JPL, said Titan's subsurface water may have frozen in the past and could now be melting, or the moon's hydrosphere might be gradually freezing solid.

Computer models indicate these ice, slush and water layers extend more than 340 miles deep. An outer ice shell about 100 miles thick covers layers of slush and water pools that reach down another 250 miles.

The breakthrough came from improved analysis of how Saturn's gravity affects Titan. Because Titan is tidally locked to Saturn—always showing the same face to the planet—Saturn's gravitational pull deforms the moon's surface, creating bulges up to 30 feet high.

In 2008, scientists first proposed that Titan must possess a huge ocean beneath the surface to allow such significant deformation. But the new study introduces a crucial detail: timing.

Petricca's team measured a 15-hour delay between the peak gravitational pull and the rise of Titan's surface. Like a spoon stirring honey, it takes more energy to move a thick, viscous substance than liquid water. A liquid ocean would respond immediately, Petricca explained, but the delay indicates a slushy ice interior with liquid water pockets.

"Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan. That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan's interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses," Petricca said.

Journaux's planetary cryo-mineral physics laboratory at UW helped ground the results by simulating the extreme pressures found deep inside Titan.

"The watery layer on Titan is so thick, the pressure is so immense, that the physics of water changes. Water and ice behave in a different way than seawater here on Earth," he said.

Skepticism Remains

Sapienza University of Rome’s Luciano Iess, whose previous studies using Cassini data indicated a hidden ocean at Titan, is not convinced by the latest findings.

While “certainly intriguing and will stimulate renewed discussion ... at present, the available evidence looks certainly not sufficient to exclude Titan from the family of ocean worlds," Iess said in an email to AP.

NASA’s planned Dragonfly mission — featuring a helicopter-type craft due to launch to Titan later this decade — is expected to provide more clarity on the moon’s innards. Journaux is part of that team.

The mission should arrive at Titan in 2034, becoming the second flying vehicle on another world besides Earth, after Ingenuity, the Mars helicopter. Dragonfly's surface observations are hoped to reveal more about where life may be lurking and how much water might be available for organisms. Journaux is part of that mission team.

Titan joins other moons suspected of harbouring water beneath their surfaces. Jupiter's moon Ganymede is slightly larger than Titan and may have an underground ocean. Saturn's Enceladus and Jupiter's Europa are also believed to be water worlds, with geysers erupting from their frozen crusts.

Saturn has 274 known moons, the most in the solar system.

The Cassini mission began in 1997 and lasted nearly 20 years, orbiting the ringed planet and studying its moons before intentionally diving into Saturn's atmosphere in 2017.

Saturn’s biggest moon might not have an ocean after all

University of Washington

image:

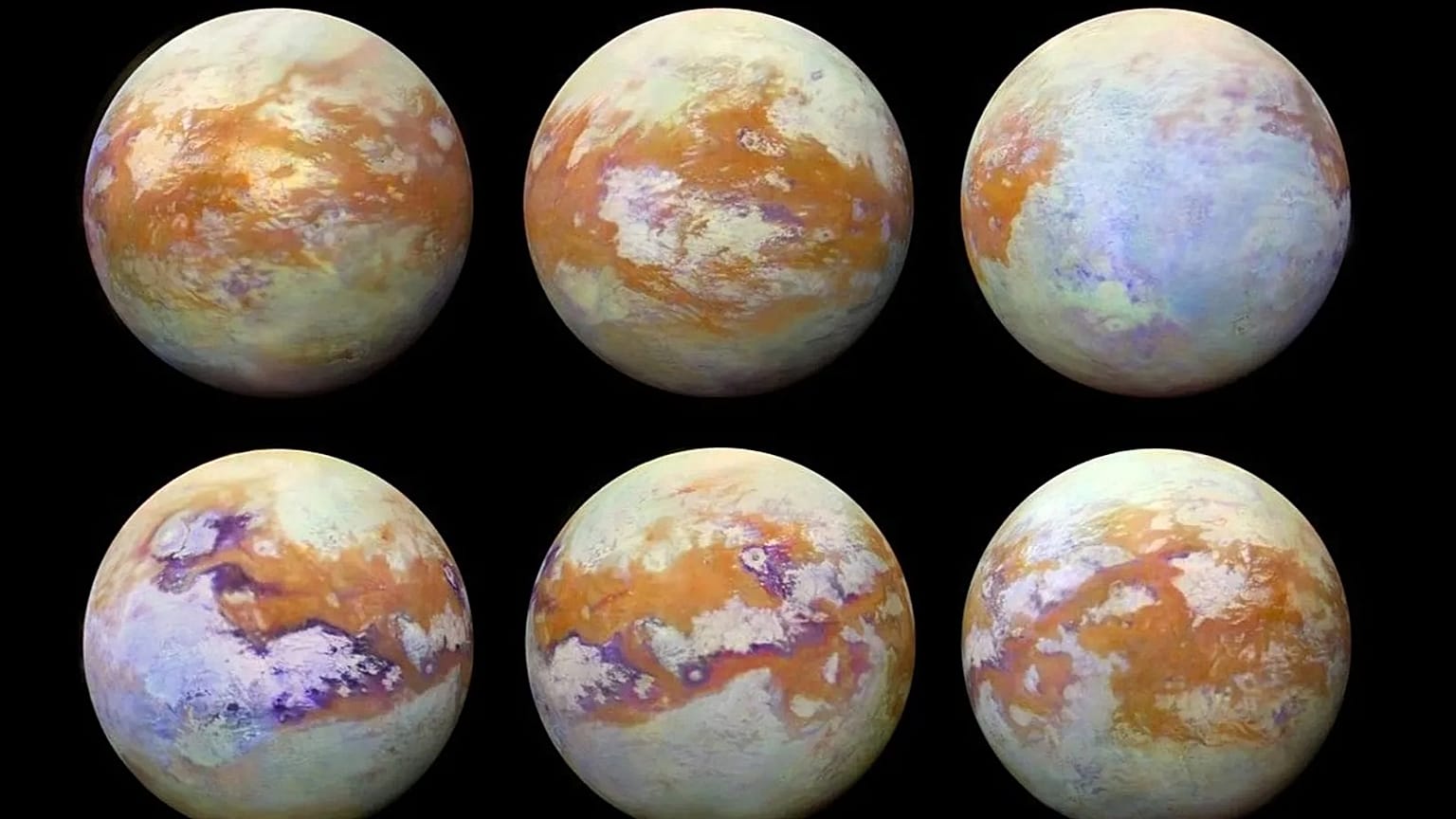

The six infrared images of Titan above were created by compiling data collected over the course of the Cassini mission. They depict how the surface of Titan looks beneath the foggy atmosphere, highlighting the variable surface of the moon.

view moreCredit: NASA - https://science.nasa.gov/image-detail/amf-7c2a49e6-2a2d-4cac-ba34-9cdf257db3ec/

Careful reanalysis of data from more than a decade ago indicates that Saturn’s biggest moon, Titan, does not have a vast ocean beneath its icy surface, as suggested previously. Instead, a journey below the frozen exterior likely involves more ice giving way to slushy tunnels and pockets of meltwater near the rocky core.

Data from NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn initially led researchers to suspect a large ocean composed of liquid water under the ice on Titan. However, when they modeled the moon with an ocean, the results didn’t match the physical properties described by the data. A fresh look yielded new — slushier — results. The findings could spark similar inquiries into other worlds in the solar system, and help narrow the search for life on Titan.

“Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers, which has implications for what type of life we might find, but also the availability of nutrients, energy and so on,” said Baptiste Journaux, a University of Washington assistant professor of Earth and space sciences.

The study, published Dec. 17 in Nature, was led by NASA with collaboration from Journaux and Ula Jones, a UW graduate student of Earth and space sciences in his lab.

The Cassini mission, which began in 1997 and lasted nearly 20 years, produced volumes of data about Saturn and its 274 moons. Titan — shrouded by a hazy atmosphere — is the only world, apart from Earth, known to have liquid on its surface. Temperatures hover around -297 degrees Fahrenheit. Instead of water, liquid methane forms lakes and falls as rain.

As Titan circled Saturn in an elliptical orbit, the researchers observed the moon stretching and smushing depending on where it was in relation to Saturn. In 2008, they proposed that Titan must possess a huge ocean beneath the surface to allow such significant deformation.

“The degree of deformation depends on Titan’s interior structure. A deep ocean would permit the crust to flex more under Saturn’s gravitational pull, but if Titan were entirely frozen, it wouldn’t deform as much,” Journaux said. “The deformation we detected during the initial analysis of the Cassini mission data could have been compatible with a global ocean, but now we know that isn’t the full story.”

In the new study, the researchers introduce a new level of subtlety: timing. Titan’s shape shifting lags about 15 hours behind the peak of Saturn’s gravitational pull. Like a spoon stirring honey, it takes more energy to move a thick, viscous substance than liquid water. Measuring the delay told scientists how much energy it takes to change Titan’s shape, allowing them to make inferences about the viscosity of the interior.

The amount of energy lost, or dissipated, in Titan was much greater than the researchers expected to see in the global ocean scenario.

“Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan. That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses,” said Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who led the study.

The model they propose instead features more slush and quite a bit less liquid water. Slush is thick enough to explain the lag but still contains water, enabling Titan to morph when tugged.

Petricca arrived at this conclusion by measuring the frequency of radio waves coming from the Cassini spacecraft during Titan fly-bys, and Journaux helped ground the results with thermodynamics. Journaux studies water and minerals under extreme pressure to gauge the potential for life on other planets.

“The watery layer on Titan is so thick, the pressure is so immense, that the physics of water changes. Water and ice behave in a different way than sea water here on Earth,” Journaux said.

His planetary cryo-mineral physics laboratory at UW has spent years developing the methods to simulate extraterrestrial environments in the lab. He was able to provide Petricca and colleagues with a dataset describing the anticipated physical properties of water and ice deep inside Titan.

“We could help them determine what gravitational signal they should expect to see based on the experiments made here at UW,” Journaux said. “It was very rewarding.”

“The discovery of a slushy layer on Titan also has exciting implications for the search for life beyond our solar system,” Jones said. “It expands the range of environments we might consider habitable.”

Although the notion of an ocean on Titan invigorated the search for life there, the researchers believe the new findings might improve the odds of finding it. Analyses indicate that the pockets of freshwater on Titan could reach 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Any available nutrients would be more concentrated in a small volume of water, compared to an open ocean, which could facilitate the growth of simple organisms.

While it is unlikely that the researchers discover fish wriggling through slushy channels, if life is found on Titan, it may resemble polar ecosystems on Earth.

Journaux is on the team for NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission to Titan, scheduled for launch in 2028. The data collected here will guide the mission and Journaux hopes to return with some evidence of life on the planet and a definitive answer about the ocean.

Co-authors include Steven D. Vance, Marzia Parisi, Dustin Buccino, Gael Cascioli, Julie Castillo-Rogez, Mark Panning and Jonathan I. Lunine from NASA; Brynna G. Downey at Southwest Research Institute; Francis Nimmo and Gabriel Tobie from the University of Nantes; Andrea Magnanini from the University of Bologna; Amirhossein Bagheri from the California Institute of Technology and Antonio Genova from Sapienza University of Rome.

This research was funded by NASA, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Italian Space Agency.

For more information, contact Journaux at bjournau@uw.edu or Petricca at flavio.petricca@jpl.nasa.gov.

This story was adapted from a press release by NASA.

Journal

Nature

Article Title

Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean

Article Publication Date

17-Dec-2025

This illustration shows the various ways Titan might respond to Saturn’s gravitational pull depending on its interior structure. Only the slushy interior produced the bulge and lag observed in the new study.

Credit

Baptiste Journaux and Flavio Petricca

No comments:

Post a Comment