Who Really Owns Syria’s Oil and Gas Comeback?

- Syria’s central government regained control of most of its oil and gas assets in January 2026, reopening a key revenue stream after output collapsed from 380,000 b/d to about 80,000 b/d before al-Assad’s ouster.

- As Shell handed over its stake in the al-Omar field to the Syrian Petroleum Company and US majors ConocoPhillips and Chevron expressed their readiness to step in, the investment map shifted sharply.

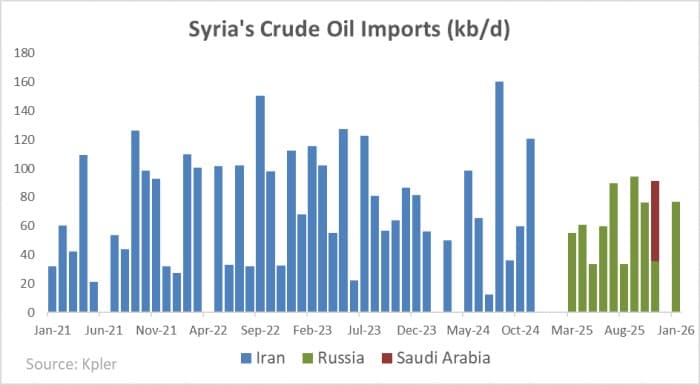

- With Iran having stopped crude shipments after the fall of the al-Assad regime in late 2024, Russia is now the only major crude and oil products supplier into the country, averaging 115,000 b/d of crude and clean product exports in January 2026.

Syria’s attempt to rebuild its oil and gas sector entered a new phase in January 2026, when forces of the al-Sharaa government pushed into territories long controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and forced a new ceasefire. Under the agreement reached on January 18, Damascus assumed administrative and security control over all major oil and gas assets previously held by the SDF in the northeast of the country. For the first time since 2011, the Damascus government regained effective authority over most of the country’s hydrocarbon resources, reopening a vital revenue stream but also exposing the sector to renewed political and commercial risk.

Before the conflict, Syria produced about 380,000 b/d of oil and 25.5 Mcm/d of natural gas. As fighting spread following the onset of Syria’s bloody civil war in 2011, output collapsed. Oil production fell by roughly 80% to around 30,000 b/d in the first years of the conflict, while gas output halved to about 12 Mcm/d. Gas declined less sharply because most major fields are located in the Palmyra basin near Damascus, which remained relatively secure and under government control. Oil, by contrast, is concentrated in northeastern Syria, where fighting was the most intense. These heavy-oil fields were controlled for years by the SDF, the main rivals of the Assad-led central government. As long as these areas remained outside state control, Syria’s energy recovery remained structurally constrained. After the fall of al-Assad’s regime in late 2024, throughout 2025, negotiations between the government and the SDF continued intermittently while clashes persisted. The balance shifted in January 2026, when government forces advanced into SDF-held territory and secured a new ceasefire. Damascus assumed control over Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa governorates and over all major oil and gas assets that were previously held by the SDF, including the Al-Omar and Tanak oilfields and the Conoco gas plant.

Syria’s investment breakthrough also began after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, when Western governments gradually eased economic restrictions. In June 2025, the US lifted sanctions on the Syrian Petroleum Company (SPC), following similar steps by the EU and the UK. Banking restrictions were relaxed and limited access to SWIFT was restored. However, the first to come back to the country were Gulf partners. Saudi Arabia emerged as a central partner, signing agreements in August 2025 covering gas field development, drilling, processing and solar projects, while the Saudi Electricity Company agreed to cooperate on power generation and grid infrastructure. In November, UAE-based Dana Gas signed a deal to evaluate existing gas fields, and in December Saudi Arabia added four further energy agreements.

Gas, less damaged than oil infrastructure and directly linked to chronic electricity shortages, became the main focus of early reconstruction and investment. The World Bank approved a $146 million four-year programme to stabilise transmission and distribution networks. Syria also resumed gas exploration, launching four wells near Damascus in Al-Tuwani in late 2025, with first output expected in mid-2026. A Qatar-led consortium pledged $7 billion to build new gas-fired power plants, and in August 2025 Syria began importing Azerbaijani gas via Turkey through the Kilis–Aleppo pipeline, targeting volumes of about 1.2 billion cubic metres a year.

Western re-engagement has been cautious and limited in scope so far. Syria’s oil sector remains highly exposed to risks, shaping investor behaviour. In late January 2026, Shell announced it would exit its stake in the Al-Omar field and transfer it to the SPC. The company had lacked access to the asset during years of SDF control and chose not to re-engage after the takeover, consistent with its broader retreat from high-risk jurisdictions, including earlier withdrawals from Iraq’s Majnoon field in 2018 and Nigeria’s onshore assets in 2024.

Although the CEO of the SPC announced plans to award exploration licences to TotalEnergies and Eni, the European majors remain cautious. This way, the most likely new entrants are US companies, which benefit from strong political and security backing. In November 2025, ConocoPhillips signed preliminary agreements with the SPC and Novaterra to develop gas assets and expand exploration. On February 4, Chevron and Qatar-based Power International Holding signed a memorandum of understanding with the SPC for the development of the country’s prospective offshore oil and gas assets, with plans to start first drillings already in summer 2026.

Alongside Western and Gulf re-engagement, Russia remains the most active external player both before and after the war. Russian companies were present even before 2011, when Tatneft began operating in Deir ez-Zor under a PSA with the SPC. Exploration halted after the conflict erupted, but Moscow’s role expanded during the war through security-linked arrangements that granted small Russian firms access to oilfields captured from the Islamic State by Russian-backed private forces. Under al-Assad, Iran became Syria’s main oil supplier, providing most imported crude and fuel under sanctions and keeping refineries operational. That support ended after the regime’s collapse in late 2024, allowing Russia to move quickly into the gap. From early 2025, Moscow began shipping crude and refined products to Syria, starting with ARCO blend cargoes in March – effectively preventing refinery shutdowns – followed by Urals crude and clean products. In January 2026, Russian exports of crude and fuels to Syria reached about 115,000 b/d, according to Kpler data.

The Syrian government began testing crude exports after sanctions were eased in mid-2025, with the SPC probing demand in Mediterranean markets. One crude oil cargo sailed from the Tartous terminal in September 2025 –ultimately bound to Sardinia, home to Vitol’s Saras refinery, one of the region’s most sophisticated facilities. Syrian crude is difficult to market: it is heavy (around 23 degrees API), high in sulphur (about 4%), and, according to Energy Intelligence, with a big water cut. Only complex refiners capable of processing contaminated heavy grades can absorb such barrels. The main attraction, however, is price. SPC cargoes were reportedly offered at around $10 discount to Brent, making them the cheapest sanction-free heavy crude in the Mediterranean region. Refiners willing to take on these operational challenges stand to gain most from Syria’s return to oil markets.

The uneven return of foreign capital to post-Assad Syria reflects intensifying geopolitical competition, as Russian and Western interests increasingly converge on the same energy assets and infrastructure. Moscow is seeking to preserve the privileged economic and political position it built during the war and reinforced through fuel supplies, while Western governments and companies view energy engagement as a channel for stabilisation and political influence. For Damascus, managing this rivalry has become a central political task. Russia remains a key partner, offering geographic proximity, logistical access, and reliable fuel flows, while Western involvement brings capital, technology, and international legitimacy. Security considerations underpin this balance: Washington’s decision to limit support for Kurdish forces and shift backing toward Damascus weakened the SDF, enabling the January 2026 takeover of key oilfields, and making Western military and diplomatic support the main external guarantee of Syria’s territorial consolidation.

Syria’s energy recovery is therefore inseparable from its foreign policy alignment. The government must rely on Russia for immediate stability while signalling loyalty to Western partners to secure long-term investment and security guarantees. Gas-linked power generation is likely to recover first, reflecting its role in economic and social stabilisation. Oil output will recover more slowly, constrained by infrastructure damage, investor caution and political risk. Whether Damascus can navigate this perfect storm of competing interests and convert regained oilfields into sustainable growth, rather than renewed dependency, will determine the durability of its post-war settlement.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment