Inside Strum: How a Subscription Platform Funds Ukraine’s Neo-Nazi Azov Brigade

One of the most persistent myths in Western political thought is the idea that the United States and its European allies are principled opponents of fascism and totalitarianism. This doctrine, which many Washington elites believe at an almost religious level, has served as the basis for the ongoing proxy war in Ukraine. Numerous politicians from both sides of the proverbial aisle have accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of being a Nazi or a fascist. However, when the United States allows Neo-Nazi-linked Ukrainian organizations like the Azov Brigade to receive support, this undermines their narrative.

Now, after American and European taxpayers have already paid billions for Ukraine’s war, the Azov Brigade is attempting to extract more money from Westerners via a subscription service called “Strum.” But before discussing Strum, it is important to examine what the Azov Brigade is and why it requires additional funding in the first place.

The Azov Brigade (formerly known as the Azov Battalion and Azov Regiment) has been mired in controversy since its founding. The organization was founded in 2014 by Andrey Biletskyi, a political activist with ties to Neo-Nazi movements. The Azov Brigade began as an amalgamation of radical movements including the Patriot of Ukraine gang which “espoused xenophobic and neo-Nazi ideas, and was engaged in violent attacks against migrants, foreign students in Kharkiv and those opposing its views.” Following the Maidan Revolution, oligarchs and elements of the Ukrainian government backed the organization which was then incorporated into the National Guard of Ukraine. In 2016, the UN alleged that the Azov regiment violated international law due to its documented mass looting of civilian homes, its targeting of civilian areas, and its treatment of prisoners. During the Siege of Mariupol, the group was heavily involved in the fighting on the Ukrainian side though it eventually surrendered to Russia. In 2023, the Azov Regiment was reorganized into the Azov Brigade.

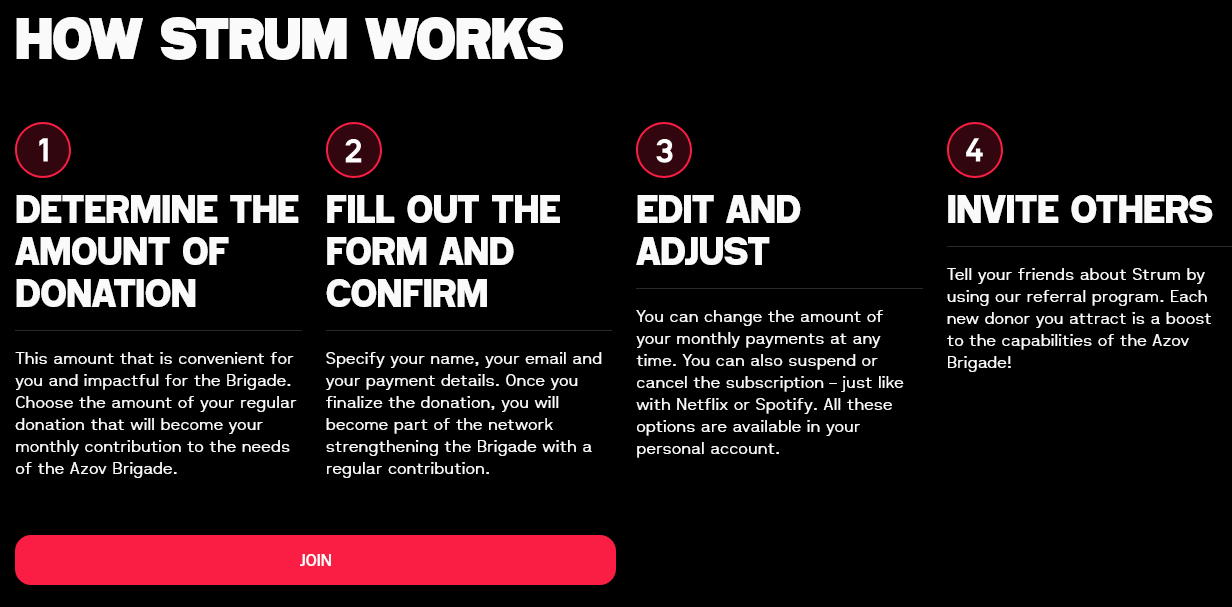

With resources dwindling and rampant foreign military aid corruption, Azov has increasingly relied on donations from individuals and companies. According to reporting from Svidomi, which included interviews with founders and project managers, a new project, Strum, has become the “driving force” behind the Brigade. The platform operates as a subscription service like Netflix or Spotify, but with some substantial differences and additional features.

Donors choose how much they give per month giving the Azov Brigade a consistent “electric current” of funding for vehicles, drones, fuel, and whatever else the Brigade might need. In return, donors get access to a members-only Telegram channel. Additionally, its referral program incentivises donors to spread the word.

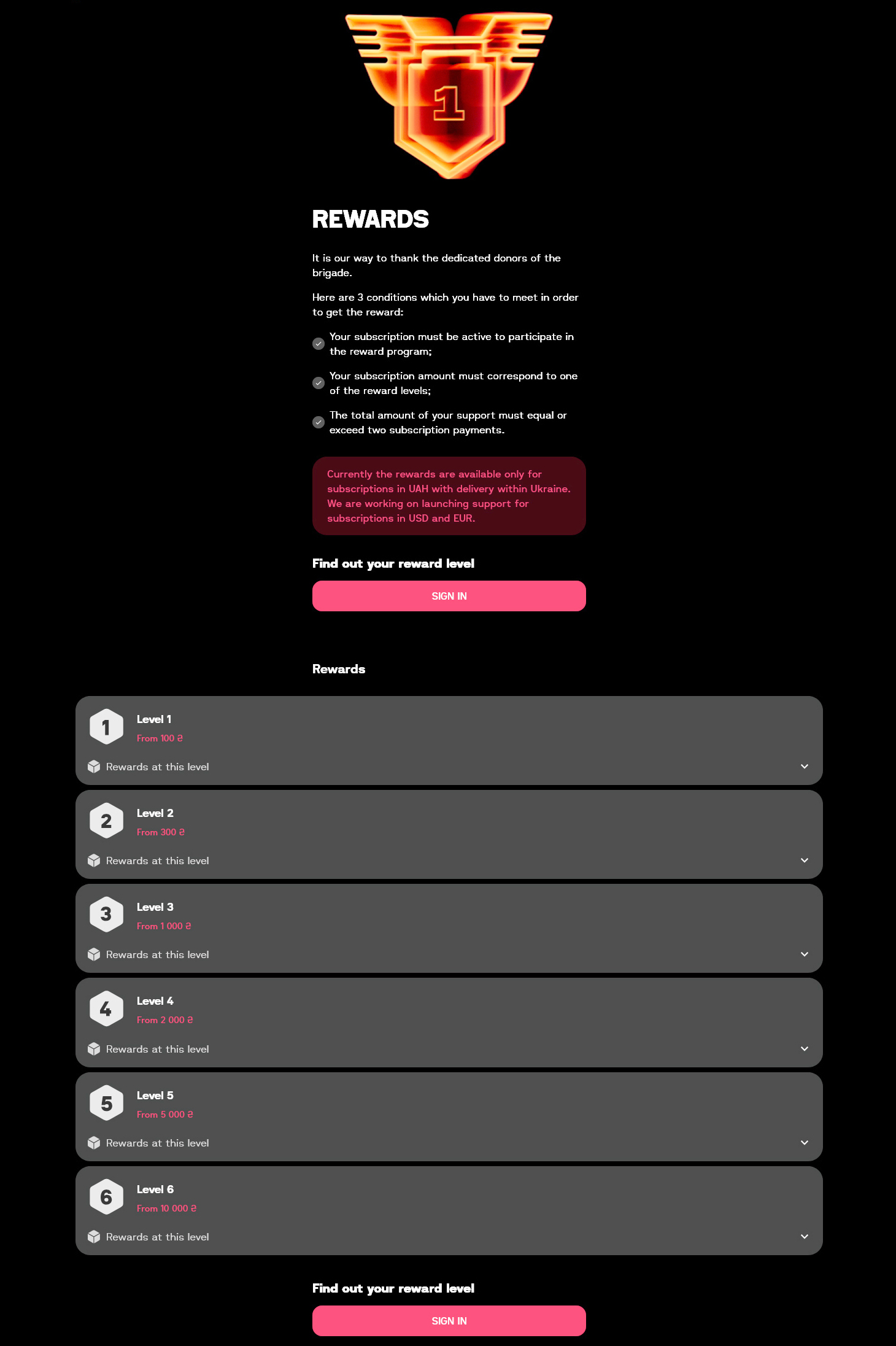

Strum has a rewards program where you can get access to different merchandise and raffles depending on how much you give.

Launched on October 14, 2024, the timing of its founding is not merely an interesting factoid. Indeed, major changes in how the American government views the Azov Brigade occurred mere months prior to its establishment. On June 11, 2024, the US lifted its ban on providing weapons and training to the Azov Brigade. Commentators described this as part of a Western effort to “release the reins” on Ukraine to allow them to attack Russia at maximum capacity.

Strum emerged in the midst of this newly permissible environment, which reduced barriers to Western support. According to Strum’s creator and project manager, Dmytro Horshkov, “The Ukrainian “donation market” is significant but not unlimited. Strum… aims to attract foreign support.” This is why they make use of the Stripe payment platform as it is “very trusted in the West.” Additionally, the company also records some promotional videos in English. However, the project also has significant domestic backers including numerous corporate benefactors.

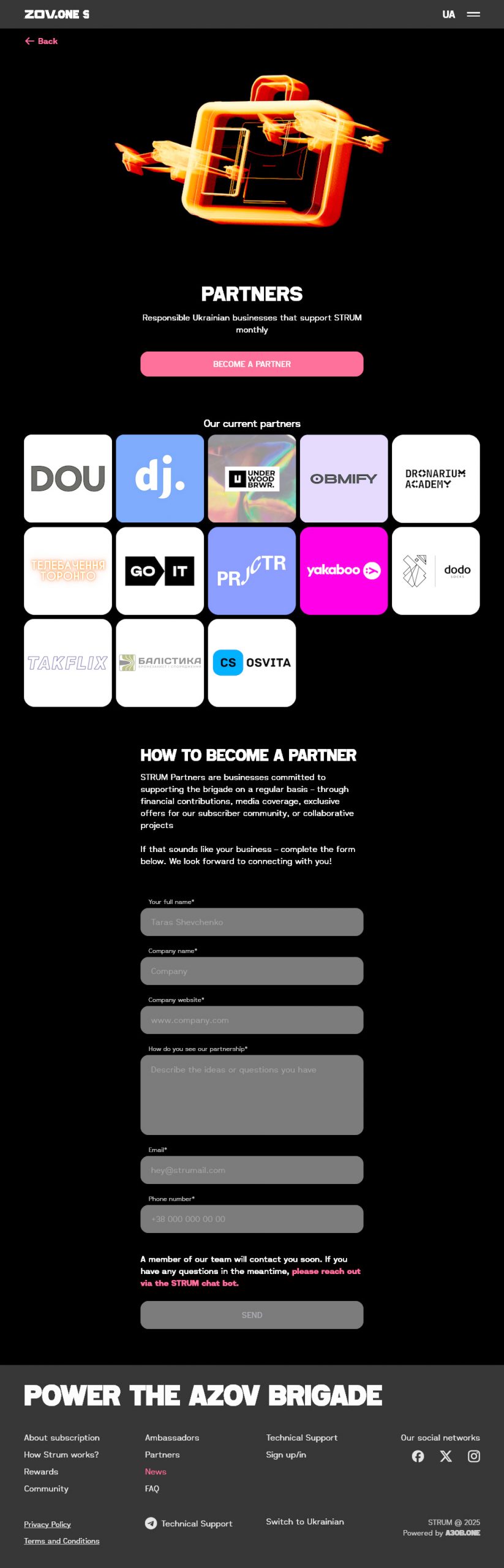

Strum lists numerous Ukrainian companies of varying sizes and industries as backers. Some companies are more related to the defense industry like Balistika, which is a manufacturer of body armor and military equipment, and Dronarium Academy, which has trained over 16,000 Ukrainian drone pilots and develops drone technology for the Ukrainian government. Other companies like Underwood Brewery or Dodo Socks appear to have little to do with technology or defense. DOU, Djinni, GoIT, Prjctr, and CS Osvita are all related to IT while Obmify is a cryptocurrency exchange platform. A number of supporters are involved in digital or print media including Yakaboo (book publishing), Toronto Television (satirical news), and Taxflix (Ukrainian movie streaming). Together, these companies form part of the larger Strum donor network which helps the Azov Brigade fund its operations while also normalizing itself amongst the business community and the public at large.

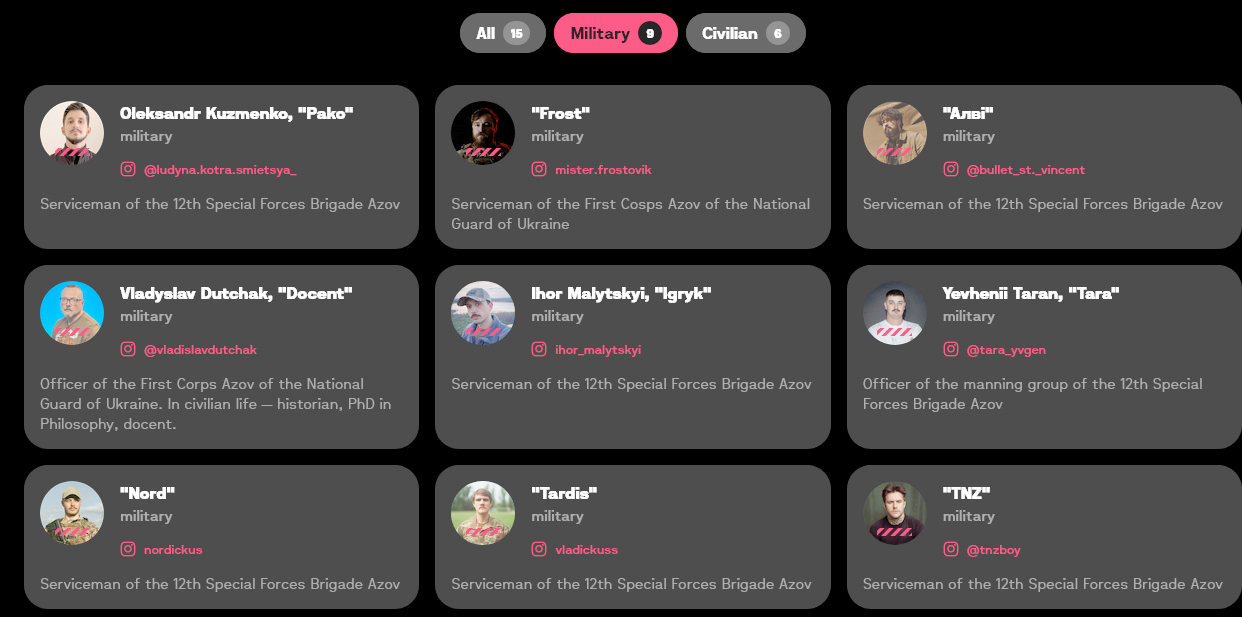

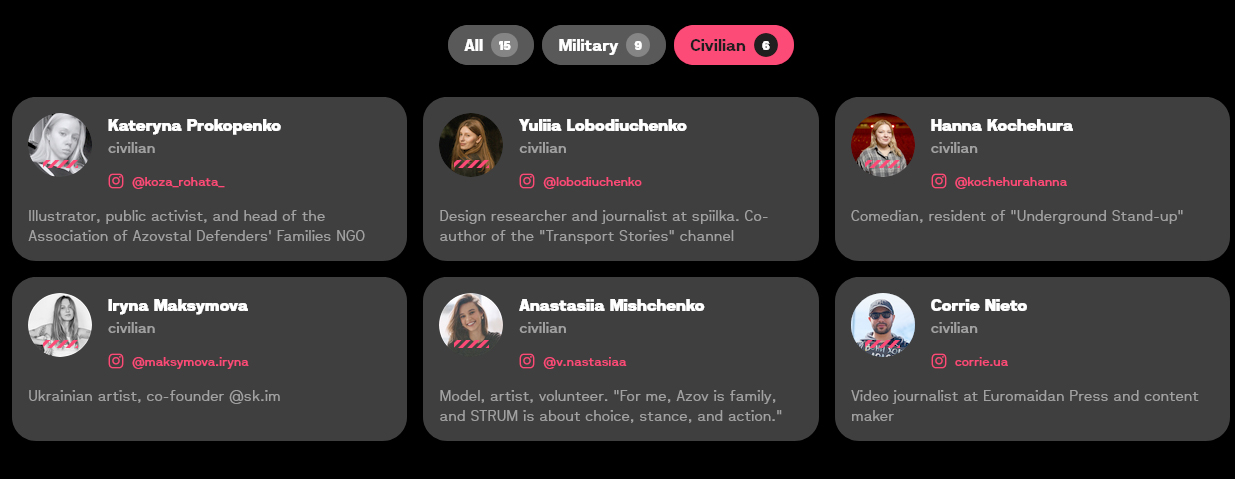

The Azov Brigade’s social media strategy to promote Strum is notably savvy, making use of both military and civilian influencers. As Strum’s lead designer Mykyta Malyshev put it, “On social media, it’s a competition for just three seconds of someone’s attention… The subscription also needed a well-communicated message. Many foundations have similar services, and the Brigade itself had something like a subscription, but it didn’t attract many signups. We need to grab attention and then convey importance.”

Most of their military influencers are from the standard Azov Brigade but some are part of the 1st Corps of the Ukrainian National Guard “Azov,” a special forces battalion within the broader Azov organization. Most of the military influencers have small platforms of five thousand or less followers; however, Mykola Kush and Maksym Yemelyanenko both have noteworthy followings at around 66,000 and 24,000 followers respectively.

Some of Kush’s following can be attributed to his release in a prisoner swap facilitated by Turkey. The swap saw 215 Ukrainian soldiers (108 from the Azov Brigade) exchanged for 55 Russian soldiers and Viktor Medvedchuk. Regardless of follower counts, the purpose of each of the military influencers is clear: to make the Azov Brigade seem “cool.” Posts frequently feature the influencers in their military gear brandishing weapons. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, civilians also make up a significant portion of their influencers.

Much like the Israel Defense Forces who use attractive women as part of their social media propaganda campaigns, the Azov Brigade employs a similar strategy. Out of the six civilian influencers, five are women, all of whom are conventionally attractive, which helps the Brigade garner more attention. Unlike the military influencers, all of the civilian influencers boast follower counts between 10,000 and 55,000. Four out of six of the influencers are artists with the remaining two being journalists.

Unlike his fellow civilian influencers, Corrie Nieto is a male from America. As stated in his bio, he works for Euromaidan Press, which is funded by the George Soros-backed International Renaissance Foundation. Nieto has covered some globally significant topics including Ryan Wesley Routh’s failed assassination of President Donald Trump. Interestingly, Nieto was able to get an interview with an unnamed source who claims to have known Routh during his time in Ukraine, illustrating the reach and access of some Azov-associated media figures. Nieto is not the only American who has developed an affinity for the Azov Battalion. As previously mentioned, the US government itself appears to view the Azov Battalion as a legitimate force in Ukraine regardless of the organization’s numerous documented human rights abuses.

At the end of the day, Strum represents far more than just a funding source for one military unit. It represents a new model of grassroots militarism which fuses companies, social media influencers, and foreign citizens into a cash cow for armed, extremist groups. Strum successfully blurs the line between consumer culture in the digital age and warfare. By doing this, it shifts responsibility away from governments and towards the individual. This raises an uncomfortable question: if the Azov Brigade is able to turn war into a participatory, monetized, and international experience, how many other groups might use similar tactics?

J.D. Hester is an independent writer born and raised in Arizona. He has previously written for Antiwar.com, Asia Times, The Libertarian Institute, and other websites. You can send him an email at josephdhester@gmail.com. Follow him on X (@JDH3ster).