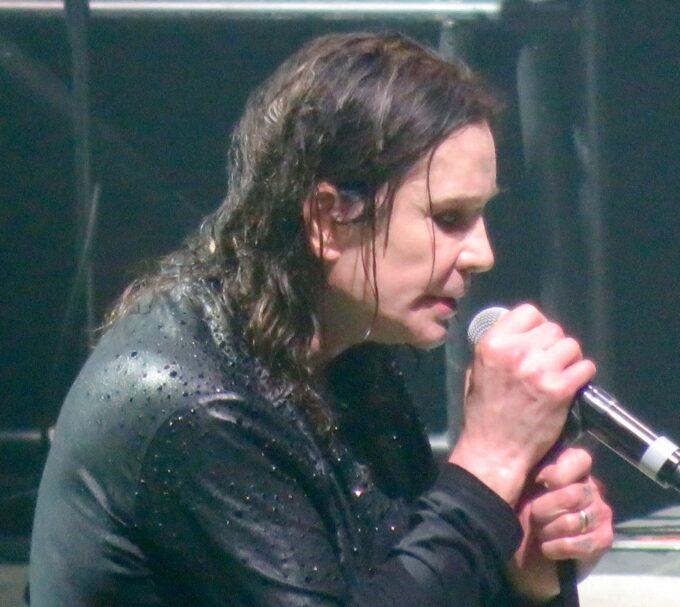

Image by Paul Arky.

Paul Bley: The Logic of Chance

Written by Arrigo Cappelletti in 2004.

Translated from the Italian by Gregory Burk in 2010.

Published by Vehicule Press, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Who is Paul Bley? Much of the curiosity about this enigmatic jazz pianist is the result of an aura of mystery which Bley appears to have cultivated. Born in Montreal in 1932, he was filling in for the great Oscar Peterson as a teenager. Peterson introduced him to Charlie Parker and all the other birds migrating through Montreal. Next thing you know, Paul Bley moved to Manhattan at age 18 and enrolled at Juilliard in 1950.

Oh, to be a pianist sitting at the center of the bebop revolution in New York in 1950 – what an incredible life! The clubs, the nightlife, the music, the city! Bley blows into town, 18 years old, a fully-formed pianist who had played with Bird, filled in for Oscar, and could stroll the piano like Bud Powell. His first recording as a leader, in 1953, features Charles Mingus on bass and Art Blakey on drums, both legendary leaders of monumental jazz bands.

Paul Bley’s second release as a leader the following year, the self-titled album, Paul Bley, features less well-known but formidable support from drummer Al Levitt and bassists Percy Heath and Peter Ind. Levitt and Ind were both students of the blind pianist, Lennie Tristano, who ran a cult-like studio where he and Charlie Parker and Charlie Mingus worked out a lot of the ideas of bebop and “east coast jazz.”

In addition to Peter Ind, Tristano taught Lee Konitz, Warne Marsh, Billy Bauer, Ronnie Ball and Sal Mosca. In a book by Peter Ind devoted to his teacher, entitled JazzVisions: Lennie Tristano and his Legacy, Ind says that Paul Bley frequently came by Lennie Tristano’s home/studio. Bley was certainly familiar with The Tristano Method by that time, as were the other members of his trios.

The Tristano Method is to learn a song by singing it – all of it – the melody, the bridge, the solos, until the song is memorized. Then the song is played in every possible key signature, until the soloist can move the melody around, up and down, through all the keys. Then the song is played at varying tempos and time signatures. Through this process – worked out together by Lennie Tristano and Charlie Parker – every song is essentially memorized, taken apart, and reassembled in a way suited to the soloist.

Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane both used this method, notoriously practicing for hours on end in a way that exhausted less determined players. Many other horn players, emulating Bird, also indirectly learned The Tristano Method through imitation. The pianists who could play this way predated Paul Bley, but not by much, and included Bud Powell, Oscar Peterson and Ahmad Jamal. If you listen to Paul Bley’s first albums with Peter Ind or Charles Mingus from the early 1950s, you would be hard pressed to distinguish him from Ahmad Jamal’s trio from the same era.

The formula was established: Play a tune until you can remake it, then put your own name on it. Like his contemporary, pianist Bill Evans, who Paul Bley is credited with mentoring at the Lenox School of Jazz, Bley could have spent the rest of his life as the top pianist in the land, with his own band or with others, playing breathtaking variations of popular tunes. But he couldn’t take it.

Something broke. That’s the problem with The Tristano Method. Once you achieve it, you tire of it, you feel trapped by it, you have to fight your way out of it. Paul Bley just stopped playing the song, only hinting at it now and then. He began chasing a different sound, a new sound set free of rhythm, melody and harmony.

In 1957, Paul Bley started dating the cigarette girl at the Birdland jazz club, named Carla Borg. Together, they followed Chet Baker out to Los Angeles in 1957, and that’s where they changed jazz history.

***

In 1958 at the Hillcrest Club in Los Angeles, “The Fabulous Paul Bley Quintet,” as it was billed, included Paul Bley on piano, Ornette Coleman on alto saxophone, Don Cherry on pocket trumpet, Charlie Haden on bass, and Billy Higgins on drums. It is the first known recording of what would become The Ornette Coleman Quartet, destined to change The Shape of Jazz to Come. Paul Bley was proud of the fact that he was the only piano player who worked with Ornette for decades.

The Hillcrest Club recording was not pressed until 1970, so in 1958, almost no one knew about Ornette. Paul Bley returned back east in 1960 to take part in a series of workshops and recordings made by George Russell and His Orchestra. Also in the orchestra were pianist Bill Evans and saxophonist Ornette Coleman. The result was Jazz in the Space Age, a somewhat stiff performance that became the Big Bang of modern jazz.

As the pianoless Ornette Coleman Quartet flipped the post-Parker jazz world on its head, Paul Bley went a different direction. In 1961, he hooked up with clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre and bass player, Steve Swallow, to make what many people considered to be “third stream” music, a largely improvised ballet of consummate musicians intensely listening to each other. Their first recording as The Jimmy Giuffre 3 appeared on the brand-new ECM record label in 1961 and the trio toured Europe later that year.

In 1959, Carla Borg became Carla Bley, an introverted pianist whom Paul encouraged to write. And write she did! She wrote five of the nine pieces on the 1962 release, Footloose, Paul’s first album as a leader since 1957. With Steve Swallow on bass and Pete LaRoca on drums, the effervescent piano has been cited by none other than Keith Jarrett as one of the major influences on his development.

In 1963, Paul Bley accepted the piano chair for the Sonny Rollins band. The story of his selection is one of the great moments in jazz history. The audition was held at Birdland in New York and it came down to Paul Bley or Herbie Hancock. Another guy who was looking for a pianist heard about the audition and sat in: trumpeter Miles Davis. Sonny got to choose first and he picked Paul Bley. Miles “settled” for Herbie Hancock, who became a star in Miles’ second great quartet.

Sonny Rollins and Paul Bley were made for each other. They both could play one song for unimaginable lengths of time, with Bley providing the landing strip to guide Sonny’s solos back to Earth. They went into the studio with tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins to record Sonny Meets Hawk, with Bob Cranshaw on bass and Roy McCurdy on drums.

When it came time to play his solo on “All the Things You Are” – the kind of show tune jazz was moving away from – Bley never once touched the melody. Years later, guitarist Pat Metheny described Bley’s solo as “the shot heard ’round the world.” Bley told Aiden Levy, author of the mammoth biography, Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins, that “I did not play the song at all. Not only was I ‘elastically’ away from the song, I never really bounced back … [but] I always knew where I was.”

This is the story of the mystery of Paul Bley. You know he’s there. You can hear him behind you. But when you go to look for him, he vanishes. It’s like a game he plays; he’s always there but never where you’re looking.

The Sonny Rollins Band toured Japan for the first time that fall, and it had a profound impact on both Rollins and Bley. When they returned , Rollins formed a nonprofit organization to promote yoga in the United States. Bley got back with his trio of Steve Swallow on bass and Pete LaRocca on drums. That also didn’t last long. Soon Carla Bley was living with Steve Swallow and Swallow was replaced in the band by Gary Peacock, with Paul Motian replacing LaRocca on drums.

***

Biographer Arrigo Cappelletti accurately captures this mercurial nature in Paul Bley: The Logic of Chance. The cover photo is a picture of Bley’s back as he plays a grand piano. He points out that Bley always sings softly as he plays, a residue of The Tristano Method. He says Bley’s work with Jimmy Giuffre was “anchored to the silences.” Paul Bley knew how to use the absence of sound better than anyone. As the music of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman became thicker and thicker, Paul Bley’s music became thinner, purer, cleaner.

Bley returned to the U.S. only to be dumped by Sonny Rollins, dumped by his wife, Carla Bley, who was now partnered with his bass player, and thanks to Paul was becoming more famous than he was. In a chapter of Cappelletti’s book entitled, “A Brief Description of Some Compositions,” all five pieces discussed were written by Carla Bley, none by Paul. Ouch. Maybe it was a team sport, but shortly thereafter Bley started a long-term relationship with Annette Peacock, wife of his bass player Gary Peacock.

Bley bought the “first-ever” Moog synthesizer and played it almost exclusively from 1969 to 1971. In 1972 he recorded his first album of solo piano music, Open To Love, which is, of course, on ECM Records. That is the same year ECM released Keith Jarrett’s first solo album, Facing You, and Chick Corea’s first solo album, Improvisations, Volume 1. All three landmark recordings were made at the Arne Bendiksen Studio in Oslo, Norway. That must be some piano!

Bley was indeed “open to love,” as he divorced Annette Peacock and married videographer Carol Goss in 1972. Together, they founded Improvising Artists, Inc., in 1974, (https://www.improvart.com/) which put out many important recordings during its short run, including Jaco with Jaco Pastorious on bass, Paul Bley on piano, Pat Metheny on guitar, and Bruce Ditmas on drums.

One reason Paul Bley is not a household name is that he became an expatriate and moved to Europe in 1980. A similar fate happened to pianist Bud Powell and saxophonist Sidney Bechet. From 1980 to 1985, all Bley’s recordings were made in Europe. In 1985, he was reunited with his friend and former employer, Chet Baker, in Copenhagen. During the 1980s, he mostly recorded solo albums or with a revolving cast of European trios. Half of the articles written about Paul Bley in the extensive bibliography in Cappelletti’s book are not in English. Cappelletti is Italian.

In 1989, Paul Bley reunited with Jimmy Giuffre and Steve Swallow for a series of concerts in New York, as well as Charlie Haden and Paul Motian for concerts in Montreal and Milan. He remained ferociously inventive for two more decades, with new European partners and old American favorites. Carol Goss started the Not Still Art Festival in New York in 1996 which is still operating (https://www.improvart.com/nsa/).

At the age of 76, in 2008, Paul Bley gave his last performance, playing solo piano in Oslo, Norway. It was released in 2014 by ECM Records as Play Blue, an anagram of his name. He died in Florida, of all places, at the age of 83 in 2016.

Here it is, ten years later, and I ask my smart speaker to “play Paul Bley,” and she acts like I’m having a stroke. No matter how slowly I say his name, or how much I annunciate, I cannot get Amazon to play Paul Bley. Ask for Carla Bley, and she never stops going (much of it performed by Paul Bley). His autobiography, Stopping Time, is out of print; used copies sell for $60. The book, Time Will Tell: Conversations With Paul Bley, also out of print, will set you back $140 for a used copy.

A pianist who belongs with Glenn Gould and Oscar Peterson among the most famous Canada has produced, a pianist who drives several of the most important jazz recordings of all time, a pianist so ahead of the curve we have yet to catch up – Paul Bley is virtually invisible in contemporary culture. Who is Paul Bley? When you find out, you won’t believe it!