Photograph Source: Andrew Milligan sumo – CC BY 2.0

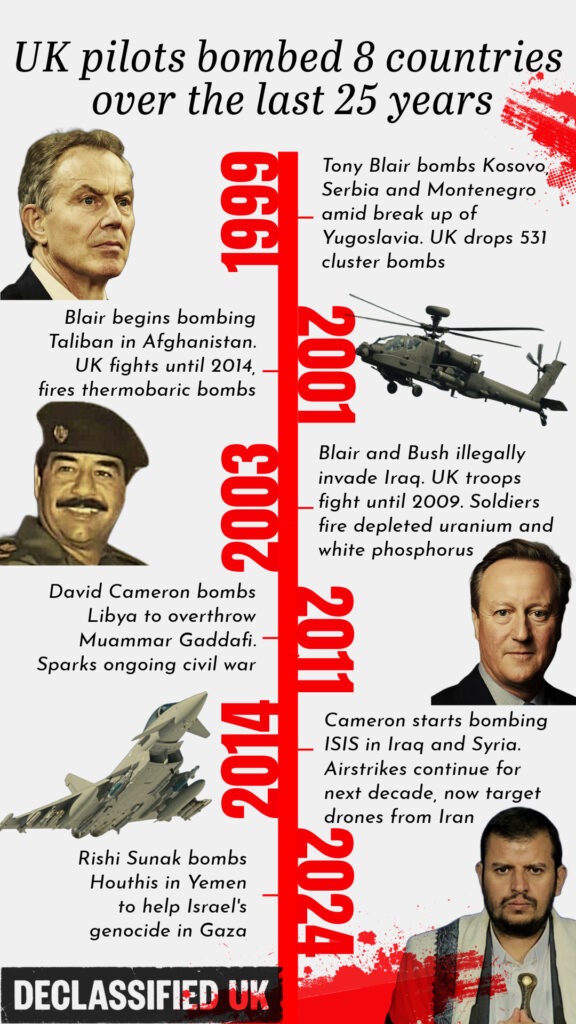

When President Clinton dropped 23,000 bombs on what was left of Yugoslavia in 1999 and NATO invaded and occupied the Yugoslav province of Kosovo, U.S. officials presented the war to the American public as a “humanitarian intervention” to protect Kosovo’s majority ethnic Albanian population from genocide at the hands of Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic. That narrative has been unraveling piece by piece ever since.

In 2008 an international prosecutor, Carla Del Ponte, accused U.S.-backed Prime Minister Hashim Thaci of Kosovo of using the U.S. bombing campaign as cover to murder hundreds of people to sell their internal organs on the international transplant market. Del Ponte’s charges seemed almost too ghoulish to be true. But on June 24th, Thaci, now President of Kosovo, and nine other former leaders of the CIA-backed Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA,) were finally indicted for these 20-year-old crimes by a special war crimes court at The Hague.

From 1996 on, the CIA and other Western intelligence agencies covertly worked with the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) to instigate and fuel violence and chaos in Kosovo. The CIA spurned mainstream Kosovar nationalist leaders in favor of gangsters and heroin smugglers like Thaci and his cronies, recruiting them as terrorists and death squads to assassinate Yugoslav police and anyone who opposed them, ethnic Serbs and Albanians alike.

As it has done in country after country since the 1950s, the CIA unleashed a dirty civil war that Western politicians and media dutifully blamed on Yugoslav authorities. But by early 1998, even U.S. envoy Robert Gelbard called the KLA a “terrorist group” and the UN Security Council condemned “acts of terrorism” by the KLA and “all external support for terrorist activity in Kosovo, including finance, arms and training.” Once the war was over and Kosovo was successfully occupied by U.S. and NATO forces, CIA sources openly touted the agency’s role in manufacturing the civil war to set the stage for NATO intervention.

By September 1998, the UN reported that 230,000 civilians had fled the civil war, mostly across the border to Albania, and the UN Security Council passed resolution 1199, calling for a ceasefire, an international monitoring mission, the return of refugees and a political resolution. A new U.S. envoy, Richard Holbrooke, convinced Yugoslav President Milosevic to agree to a unilateral ceasefire and the introduction of a 2,000 member “verification” mission from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). But the U.S. and NATO immediately started drawing up plans for a bombing campaign to “enforce” the UN resolution and Yugoslavia’s unilateral ceasefire.

Holbrooke persuaded the chair of the OSCE, Polish foreign minister Bronislaw Geremek, to appoint William Walker, the former U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador during its civil war, to lead the Kosovo Verification Mission (KVM). The U.S. quickly hired 150 Dyncorp mercenaries to form the nucleus of Walker’s team, whose 1,380 members used GPS equipment to map Yugoslav military and civilian infrastructure for the planned NATO bombing campaign. Walker’s deputy, Gabriel Keller, France’s former Ambassador to Yugoslavia, accused Walker of sabotaging the KVM, and CIA sources later admitted that the KVM was a “CIA front” to coordinate with the KLA and spy on Yugoslavia.

The climactic incident of CIA-provoked violence that set the political stage for the NATO bombing and invasion was a firefight at a village called Racak, which the KLA had fortified as a base from which to ambush police patrols and dispatch death squads to kill local “collaborators.” In January 1999, Yugoslav police attacked the KLA base in Racak, leaving 43 men, a woman and a teenage boy dead.

After the firefight, Yugoslav police withdrew from the village, and the KLA reoccupied it and staged the scene to make the firefight look like a massacre of civilians. When William Walker and a KVM team visited Racak the next day, they accepted the KLA’s massacre story and broadcast it to the world, and it became a standard part of the narrative to justify the bombing of Yugoslavia and military occupation of Kosovo.

Autopsies by an international team of medical examiners found traces of gunpowder on the hands of nearly all the bodies, showing that they had fired weapons. They were nearly all killed by multiple gunshots as in a firefight, not by precise shots as in a summary execution, and only one victim was shot at close range. But the full autopsy results were only published much later, and the Finnish chief medical examiner accused Walker of pressuring her to alter them.

Two experienced French journalists and an AP camera crew at the scene challenged the KLA and Walker’s version of what happened in Racak. Christophe Chatelet’s article in Le Monde was headlined, “Were the dead in Racak really massacred in cold blood?” and veteran Yugoslavia correspondent Renaud Girard concluded his story in Le Figaro with another critical question, “Did the KLA seek to transform a military defeat into a political victory?”

NATO immediately threatened to bomb Yugoslavia, and France agreed to host high-level talks. But instead of inviting Kosovo’s mainstream nationalist leaders to the talks in Rambouillet, Secretary Albright flew in a delegation led by KLA commander Hashim Thaci, until then known to Yugoslav authorities only as a gangster and a terrorist.

Albright presented both sides with a draft agreement in two parts, civilian and military. The civilian part granted Kosovo unprecedented autonomy from Yugoslavia, and the Yugoslav delegation accepted that. But the military agreement would have forced Yugoslavia to accept a NATO military occupation, not just of Kosovo but with no geographical limits, in effect placing all of Yugoslavia under NATO occupation.

When Milosevich refused Albright’s terms for unconditional surrender, the U.S. and NATO claimed he had rejected peace, and war was the only answer, the “last resort.” They did not return to the UN Security Council to try to legitimize their plan, knowing full well that Russia, China and other countries would reject it. When UK Foreign Secretary Robin Cook told Albright the British government was “having trouble with our lawyers” over NATO’s plan for an illegal war of aggression against Yugoslavia, she told him to “get new lawyers.”

In March 1999, the KVM teams were withdrawn and the bombing began. Pascal Neuffer, a Swiss KVM observer reported, “The situation on the ground on the eve of the bombing did not justify a military intervention. We could certainly have continued our work. And the explanations given in the press, saying the mission was compromised by Serb threats, did not correspond to what I saw. Let’s say rather that we were evacuated because NATO had decided to bomb.”

NATO killed thousands of civilians in Kosovo and the rest of Yugoslavia, as it bombed 19 hospitals, 20 health centers, 69 schools, 25,000 homes, power stations, a national TV station, the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade and other diplomatic missions. After it invaded Kosovo, the U.S. military set up the 955-acre Camp Bondsteel, one of its largest bases in Europe, on its newest occupied territory. Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner, Alvaro Gil-Robles, visited Camp Bondsteel in 2002 and called it “a smaller version of Guantanamo,” exposing it as a secret CIA black site for illegal, unaccountable detention and torture.

But for the people of Kosovo, the ordeal was not over when the bombing stopped. Far more people had fled the bombing than the so-called “ethnic cleansing” the CIA had provoked to set the stage for it. A reported 900,000 refugees, nearly half the population, returned to a shattered, occupied province, now ruled by gangsters and foreign overlords.

Serbs and other minorities became second-class citizens, clinging precariously to homes and communities where many of their families had lived for centuries. More than 200,000 Serbs, Roma and other minorities fled, as the NATO occupation and KLA rule replaced the CIA’s manufactured illusion of ethnic cleansing with the real thing. Camp Bondsteel was the province’s largest employer, and U.S. military contractors also sent Kosovars to work in occupied Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2019, Kosovo’s per capita GDP was only $4,458, less than any country in Europe except Moldova and war-torn, post-coup Ukraine.

In 2007, a German military intelligence report described Kosovo as a “Mafia society,” based on the “capture of the state” by criminals. The report named Hashim Thaci, then the leader of the Democratic Party, as an example of “the closest ties between leading political decision makers and the dominant criminal class.” In 2000, 80% of the heroin trade in Europe was controlled by Kosovar gangs, and the presence of thousands of U.S. and NATO troops fueled an explosion of prostitution and sex trafficking, also controlled by Kosovo’s new criminal ruling class.

In 2008, Thaci was elected Prime Minister, and Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia. (The final dissolution of Yugoslavia in 2006 had left Serbia and Montenegro as separate countries.) The U.S. and 14 allies immediately recognized Kosovo’s independence, and ninety-seven countries, about half the countries in the world, have now done so. But neither Serbia nor the UN have recognized it, leaving Kosovo in long-term diplomatic limbo.

When the court in the Hague unveiled the charges against Thaci on June 24th, he was on his way to Washington for a White House meeting with Trump and President Vucic of Serbia to try to resolve Kosovo’s diplomatic impasse. But when the charges were announced, Thaci’s plane made a U-turn over the Atlantic, he returned to Kosovo and the meeting was canceled.

The accusation of murder and organ trafficking against Thaci was first made in 2008 by Carla Del Ponte, the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTFY), in a book she wrote after stepping down from that position. Del Ponte later explained that the ICTFY was prevented from charging Thaci and his co-defendants by the non-cooperation of NATO and the UN Mission in Kosovo. In an interview for the 2014 documentary, The Weight of Chains 2, she explained, “NATO and the KLA, as allies in the war, couldn’t act against each other.”

Human Rights Watch and the BBC followed up on Del Ponte’s allegations, and found evidence that Thaci and his cronies murdered up to 400 mostly Sebian prisoners during the NATO bombing in 1999. Survivors described prison camps in Albania where prisoners were tortured and killed, a yellow house where people’s organs were removed and an unmarked mass grave nearby.

Council of Europe investigator Dick Marty interviewed witnesses, gathered evidence and published a report, which the Council of Europe endorsed in January 2011, but the Kosovo parliament did not approve the plan for a special court in the Hague until 2015. The Kosovo Specialist Chambers and independent prosecutor’s office finally began work in 2017. Now the judges have six months to review the prosecutor’s charges and decide whether the trial should proceed.

A central part of the Western narrative on Yugoslavia was the demonization of President Milosevich of Yugoslavia, who resisted his country’s Western-backed dismemberment throughout the 1990s. Western leaders smeared Milosevich as a “New Hitler” and the “Butcher of the Balkans,” but he was still arguing his innocence when he died in a cell at The Hague in 2006.

Ten years later, at the trial of the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, the judges accepted the prosecution’s evidence that Milosevich strongly opposed Karadzic’s plan to carve out a Serb Republic in Bosnia. They convicted Karadzic of being fully responsible for the resulting civil war, in effect posthumously exonerating Milosevich of responsibility for the actions of the Bosnian Serbs, the most serious of the charges against him.

But the U.S.’s endless campaign to paint all its enemies as “violent dictators” and “New Hitlers” rolls on like a demonization machine on autopilot, against Putin, Xi, Maduro, Khamenei, the late Fidel Castro and any foreign leader who stands up to the imperial dictates of the U.S. government. These smear campaigns serve as pretexts for brutal sanctions and catastrophic wars against our international neighbors, but also as political weapons to attack and diminish any U.S. politician who stands up for peace, diplomacy and disarmament.

As the web of lies spun by Clinton and Albright has unraveled, and the truth behind their lies has spilled out piece by bloody piece, the war on Yugoslavia has emerged as a case study in how U.S. leaders mislead us into war. In many ways, Kosovo established the template that U.S. leaders have used to plunge our country and the world into endless war ever since. What U.S. leaders took away from their “success” in Kosovo was that legality, humanity and truth are no match for CIA-manufactured chaos and lies, and they doubled down on that strategy to plunge the U.S. and the world into endless war.

As it did in Kosovo, the CIA is still running wild, fabricating pretexts for new wars and unlimited military spending, based on sourceless accusations, covert operations and flawed, politicized intelligence. We have allowed American politicians to pat themselves on the back for being tough on “dictators” and “thugs,” letting them settle for the cheap shot instead of tackling the much harder job of reining in the real instigators of war and chaos: the U.S. military and the CIA.

But if the people of Kosovo can hold the CIA-backed gangsters who murdered their people, sold their body parts and hijacked their country accountable for their crimes, is it too much to hope that Americans can do the same and hold our leaders accountable for their far more widespread and systematic war crimes?

Iran recently indicted Donald Trump for the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani, and asked Interpol to issue an international arrest warrant for him. Trump is probably not losing sleep over that, but the indictment of such a key U.S. ally as Thaci is a sign that the U.S. “accountabilty-free zone” of impunity for war crimes is finally starting to shrink, at least in the protection it provides to U.S. allies. Should Netanyahu, Bin Salman and Tony Blair be starting to look over their shoulders?