It would take 23 million years for evolution to replace Madagascar’s endangered mammals

“Now or never” for preventing extinction

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: BROWN MOUSE LEMUR, ONE OF THE 104 SPECIES OF LEMURS THAT ARE CURRENTLY THREATENED WITH EXTINCTION. A TOTAL OF 17 SPECIES OF LEMURS HAVE GONE EXTINCT SINCE HUMANS ARRIVED ON MADAGASCAR. view more

CREDIT: © CHIEN C. LEE

In many ways, Madagascar is a biologist’s dream, a real-life experiment in how isolation on an island can spark evolution. About 90% of the plants and animals there are found nowhere else on Earth. But these plants and animals are in major trouble, thanks to habitat loss, over-hunting, and climate change. Of the 219 known mammal species on the island, including 109 species of lemurs, more than 120 are endangered. A new study in Nature Communications examined how long it took Madagascar’s unique modern mammal species to emerge and estimated how long it would take for a similarly complex set of new mammal species to evolve in their place if the endangered ones went extinct: 23 million years, far longer than scientists have found for any other island.

That is, simply put, really bad news. “It's abundantly clear that there are whole lineages of unique mammals that only occur on Madagascar that have either gone extinct or are on the verge of extinction, and if immediate action isn't taken, Madagascar is going to lose 23 million years of evolutionary history of mammals, which means whole lineages unique to the face of the Earth will never exist again,” says Steve Goodman, MacArthur Field Biologist at Chicago’s Field Museum and Scientific Officer at Association Vahatra in Antananarivo, Madagascar, and one of the paper’s authors.

Madagascar is the world’s fifth-largest island, about the size of France, but “in terms of all the different ecosystems present on Madagascar, it’s less like an island and more like a mini-continent,” says Goodman. In the 150 million years since Madagascar split from the African mainland and the 80 million since it parted ways with India, the plants and animals there have gone down their own evolutionary paths, cut off from the rest of the world. This smaller gene pool, coupled with Madagascar’s wealth of different habitat types, from mountainous rainforests to lowland deserts, allowed mammals there to split into different species far more quickly than their continental relatives.

But this incredible biodiversity comes at a cost: evolution happens faster on islands, but so does extinction. Smaller populations that are specially adapted to smaller, unique patches of habitat are more vulnerable to being wiped out, and once they're gone, they're gone. More than half of the mammals on Madagascar are included on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, aka the IUCN Red List. These animals are endangered primarily because of human actions over the past two hundred years, especially habitat destruction and over-hunting.

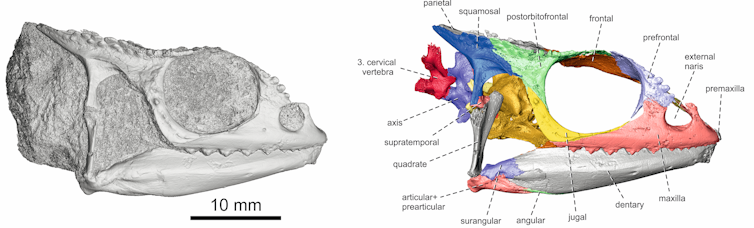

An international team of Malagasy, European, and American scientists, including Goodman, collaborated to study the looming extinction of Madagascar’s endangered mammals. They built a dataset of every known mammal species to coexist with humans on Madagascar for the last 2,500 years. (Humans have lived on the island, perhaps intermittently, for the past 10,000 years, but have remained constant there for the last 2,500.) The scientists came up with the 219 known mammal species alive today, plus 30 more that have gone extinct over the past two millennia, including a gorilla-sized lemur that went extinct between 500 and 2,000 years ago.

Armed with this dataset of all the known Malagasy mammals that interacted with humans, the researchers built genetic family trees to establish how all these species are related to each other and how long it took them to evolve from their various common ancestors. Then, the scientists were able to extrapolate how long it took this amount of biodiversity to evolve, and thus, estimate how long it would take for evolution to “replace” all of the endangered mammals if they go extinct.

To rebuild the diversity of land-dwelling mammals that have already gone extinct over the past 2,500 years, it would take around 3 million years. But more alarmingly, the models suggested that if all the mammals that are currently endangered were to go extinct, it would take 23 million years to rebuild that level of diversity. That doesn’t mean that if we let all of the lemurs and tenrecs and fossas and other unique Malagasy mammals go extinct, that evolution will recreate them if we just wait around 23 million more years. “It would be simply impossible to recover them,” says Goodman. Instead, the model means that to achieve a similar level of evolutionary complexity, whatever those new species might look like, would take 23 million years.

Luis Valente, the study’s corresponding author, says he was surprised by this finding. “It is much longer than what previous studies have found on other islands, such as New Zealand or the Caribbean,” says Valente, a biologist at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. “It was already known that Madagascar was a hotspot of biodiversity, but this new research puts into context just how valuable this diversity is. These findings underline the potential gains of the conservation of nature on Madagascar from a novel evolutionary perspective.”

According to Goodman, Madagascar is at a tipping point for protecting its biodiversity. “There is still a chance to fix things, but basically, we have about five years to really advance the conservation of Madagascar’s forests and the organisms that those forests hold,” he says.

This urgent conservation work is made difficult by inequality and political corruption that keeps land-use decisions out of the hands of most Malagasy people, says Goodman: “Madagascar’s biological crisis has nothing to do with biology. It has to do with socio-economics.” But while the situation is dire, he says, “we can't throw in the towel. We’re obliged to advance this cause as much as we can and try to make the world understand that it’s now or never.”

The critically endangered Verreaux’s Sifaka is one of the 109 species of lemurs that currently are extant on Madagascar. A total of 17 species of lemurs have already gone extinct.

CREDIT

© Chien C. Lee

JOURNAL

Nature Communications

ARTICLE TITLE

The macroevolutionary impact of recent and imminent mammal extinctions on Madagascar

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

10-Jan-2023

Endangered mammals of Madagascar: Over 20 million years of evolution under threat

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: LOWLAND STREAKED TENREC (HEMICENTETES SEMISPINOSUS). THIS IS A SPECIES OF TENREC, A DIVERSE AND UNIQUE GROUP OF MAMMALS FOUND ONLY ON MADAGASCAR. view more

CREDIT: CHIEN C. LEE

A new study reveals that it would take 3 million years to recover the number of species that went extinct due to humans on Madagascar. However, if currently threatened species go extinct, recovering them would take more than 20 million years, much longer than what has previously been found on any other island.

From unique baobab species to lemurs, the island of Madagascar is one of the world’s most important hotspots of biodiversity. Approximately 90% of its species of plants and animals are found nowhere else. After humans settled on the island 2500 years ago, Madagascar experienced many extinctions, including giant lemurs, elephant birds and dwarf hippos. However, unlike most islands, Madagascar’s fauna is still relatively intact. Over two hundred species of mammals still survive on the island, including unique species such as the fossa and the ring-tailed lemur. Alarmingly, over half of these species are threatened with extinction, primarily due to human influence. How much have humans perturbed Madagascar away from its natural state, and what is at stake if environmental change continues?

Malagasy mammals

A team of biologists and paleontologists from Europe, Madagascar and the United States set out to answer these questions by building an unprecedented new dataset describing the evolutionary relationships of all species of mammals that were present on Madagascar at the time that humans colonized the island. The dataset includes species that have already gone extinct and are only known from fossils, as well as all living species of Malagasy mammals. The researchers identified 249 species in total, 30 of which already are extinct. Over 120 of the 219 species of mammals that remain on the island today are currently classified as threatened with extinction by the IUCN Red List, due to habitat destruction, climate change and hunting.

Using a computer simulation model based on island biogeography theory, the team, led by biologists from the University of Groningen (Netherlands), Naturalis Biodiversity Center (Netherlands) and the Association Vahatra (Madagascar) found that it would take approximately 3 million years to regain the number of mammal species that were lost from Madagascar in the time since humans arrived . However, if currently threatened species go extinct, it would take much longer: about 23 million years of evolution would be needed to recover the same number of species. Just in the last decade, this figure has increased by several million years, as human impact on the island grows.

Extinction wave imminent

The staggering time it would take to recover this diversity surprised the scientists: ”It is much longer than what previous studies have found on other islands, such as New Zealand or the Caribbean”, leading researcher Luis Valente says The results of this new research, published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, suggest that an extinction wave with deep evolutionary impact is imminent on Madagascar unless immediate conservation actions are taken. However, the study finds that with adequate conservation action we may still preserve over 20 million years of unique evolutionary history on the island. Valente: “It was already known that Madagascar was a hotspot of biodiversity, but this new research puts into context just how valuable this diversity is. These findings underline the potential gains of the conservation of nature on Madagascar from a novel evolutionary perspective.”

Reference: Nathan M. Michielsen, Steven M. Goodman, Voahangy Soarimalala, Alexandra A.E. van der Geer, Liliana M. Dávalos, Grace I. Saville, Nathan Upham, Luis Valente. “The macroevolutionary impact of recent and imminent mammal extinctions on Madagascar”. Nature Communications 10 January 2023.

The Madagascar Sucker-footed Bat (Myzopoda aurita) belongs to an ancient family of bats that is found only on Madagascar.

CREDIT

Chien C. Lee

JOURNAL

Nature Communications