How microplastics are making their way into our farmland

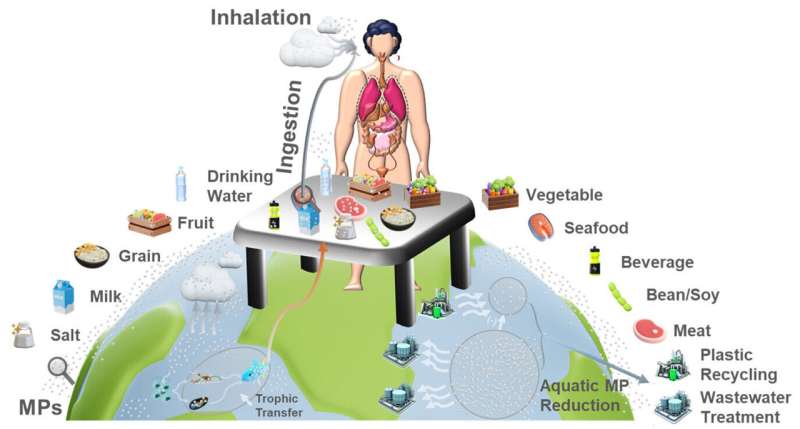

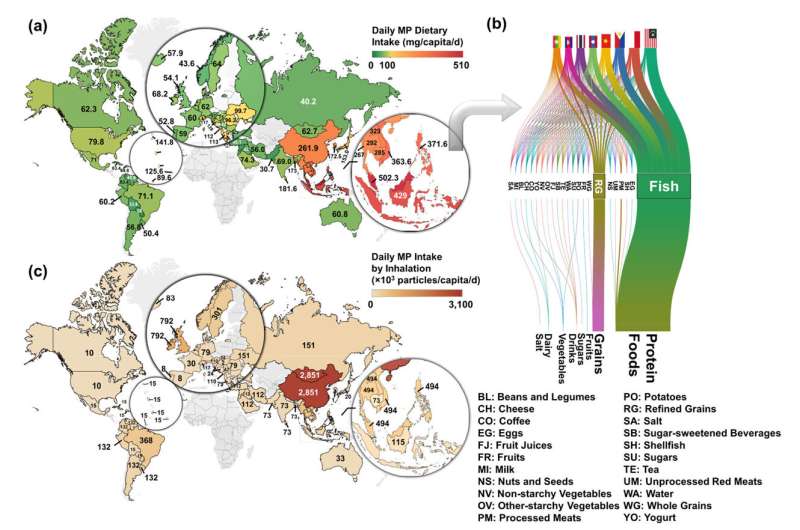

Microplastic pollution is a global environmental problem that is ubiquitous in all environments, including air, water and soils.

Microplastics are readily found in treated wastewater sludge—also known as municipal biosolids—that eventually make their way to our agricultural soils.

Our recent investigation of microplastic levels in Canadian municipal biosolids found that a single gram of biosolids contains hundreds of microplastic particles. This is a much greater concentration of microplastics than is typically found in air, water or soil.

Given that hundreds of thousands of tons of biosolids are produced every year in Canada, we need to pay close attention to the potential impacts such high levels of microplastics might have on the environment and find ways to reduce microplastic levels in Canada's wastewater stream.

Municipal biosolids

Municipal biosolids are produced at wastewater treatment plants by settling and stabilizing the solid fraction of the municipal wastewater inflow.

In Canada and around the world, municipal biosolids are used to improve agricultural farmland soil. This is because they are rich in nutrients needed for plant growth, such as phosphorus and nitrogen.

Municipal biosolid applications are carefully regulated in Canada for heavy metals, nutrients and pathogens. However, guidelines for emerging contaminants, such as microplastics, are not currently available.

While current wastewater treatment plants are not explicitly designed to remove microplastics, they are nevertheless efficient at removing nearly 90 percent of microplastic contaminants. The removed microplastics are often concentrated in the settled sludge and eventually end up in the biosolids.

Microplastics in municipal biosolids

Previous studies have shown that municipal biosolid waste is an important pathway for microplastics to enter the broader terrestrial ecosystems, including agricultural fields.

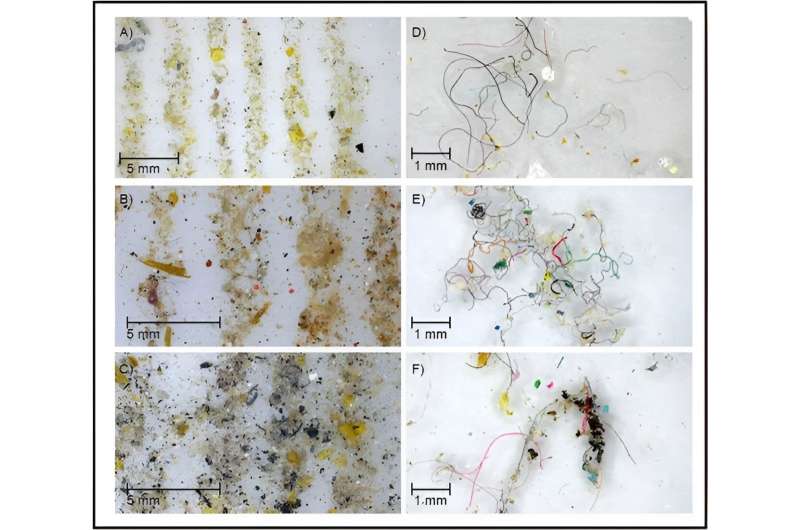

In collaboration with scientists from Environment and Climate Change Canada and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, we conducted the first pan-Canadian assessment of microplastics in municipal biosolids. We analyzed biosolid samples from 22 Canadian wastewater treatment plants across nine provinces and two biosolid-based fertilizer products.

We found hundreds of microplastic particles in every gram of biosolids. The most common type of microplastic particles we observed were microfibres, followed by small fragments. We found small amounts of glitter and foam pieces too.

Microplastic concentrations in municipal biosolids are substantially higher than other environmental networks in Canada like water, soil and river sediments. This provides further evidence that microplastics are concentrated in biosolids produced at wastewater treatment plants.

Reducing microplastics

Wastewater treatment plants are well-equipped to remove large plastics like bottle caps and plastic bags from municipal wastewater. However, microplastic particles are so small they can't be caught by current treatment infrastructure, so they end up concentrating in wastewater sludge.

As wastewater streams concentrate microplastics, they also offer an opportunity to reduce the plastic pollution that is entering the environment. While researchers across Canada are working to find insights on the short- and long-term ecological consequences of microplastic pollution on soil ecosystems, one solution is already clear.

Microplastics can be reduced at sources via systematic reductions in the use of single-use plastics, washing clothing with synthetic fiber less frequently and removing microfibres using washing machine filters. These approaches will help minimize the amount of microplastics that get into the wastewater stream and, ultimately, into the broader terrestrial and aquatic environments.

Building new technologies at our wastewater treatment plants to remove microplastics through physical or chemical means should also be explored.

We need to better understand the impact of high concentrations of microplastic on agro-ecosystems where biosolids are applied, including its impacts on soil-dwelling organisms like earthworms and insects. We also need to start building national guidelines for microplastic levels in biosolids and agricultural soils.

More information: Branaavan Sivarajah et al, How many microplastic particles are present in Canadian biosolids?, Journal of Environmental Quality (2023). DOI: 10.1002/jeq2.20497

Journal information: Journal of Environmental Quality

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Microplastic pollution: New device uses wood dust to trap up to 99.9% of microplastics in water

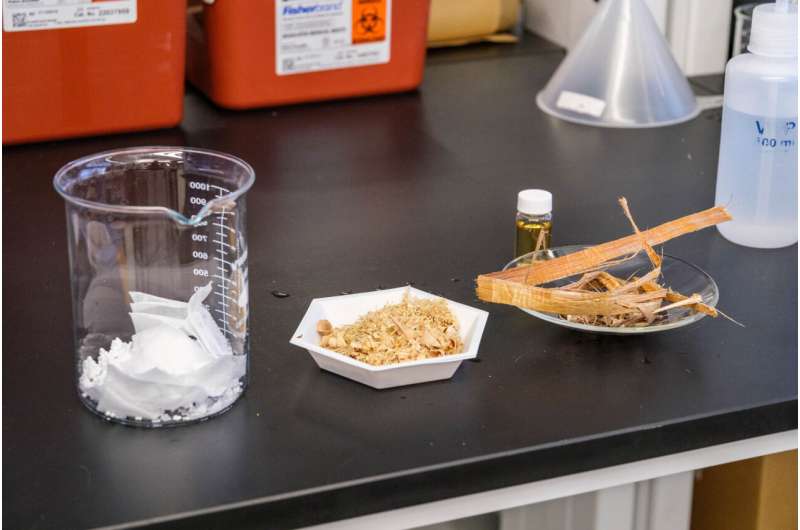

Could plants be the answer to the looming threat of microplastic pollution? Scientists at UBC's BioProducts Institute found that if you add tannins—natural plant compounds that make your mouth pucker if you bite into an unripe fruit—to a layer of wood dust, you can create a filter that traps virtually all microplastic particles present in water.

While the experiment remains a lab set-up at this stage, the team is convinced that the solution can be scaled up easily and inexpensively once they find the right industry partner.

Microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic debris resulting from the breakdown of consumer products and industrial waste. Keeping them out of water supplies is a huge challenge, says Dr. Orlando Rojas, the institute's scientific director and the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Forest Bioproducts.

He noted one study which found that virtually all tap water is contaminated by microplastics, and other research which states that more than 10 billion tons of mismanaged plastic waste will be dispersed in the environment by 2025.

"Most solutions proposed so far are costly or difficult to scale up. We're proposing a solution that could potentially be scaled down for home use or scaled up for municipal treatment systems. Our filter, unlike plastic filters, does not contribute to further pollution as it uses renewable and biodegradable materials: tannic acids from plants, bark, wood and leaves, and wood sawdust—a forestry byproduct that is both widely available and renewable."

Captures a wide variety of plastics

For their study, the team analyzed microparticles released from popular tea bags made of polypropylene. They found that their method (they're calling it "bioCap") trapped from 95.2 percent to as much as 99.9 percent of plastic particles in a column of water, depending on plastic type. When tested in mouse models, the process was proved to prevent the accumulation of microplastics in the organs.

Dr. Rojas, a professor in the departments of wood science, chemical and biological engineering, and chemistry at UBC, adds that it's difficult to capture all the different kinds of microplastics in a solution, as they come in different sizes, shapes and electrical charges.

"There are microfibers from clothing, microbeads from cleansers and soaps, and foams and pellets from utensils, containers and packaging. By taking advantage of the different molecular interactions around tannic acids, our bioCap solution was able to remove virtually all of these different microplastic types."

Collaborating on sustainable solutions

The UBC method was developed in collaboration with Dr. Junling Guo, a professor at the Center of Biomass Materials and Nanointerfaces at Sichuan University in China. Marina Mehling, a Ph.D. student at UBC's department of chemical and biological engineering, and Dr. Tianyu Guo, a postdoctoral researcher at the BioProducts Institute, also contributed to the work.

"Microplastics pose a growing threat to aquatic ecosystems and human health, demanding innovative solutions. We're thrilled that the BioProducts Institute's multidisciplinary collaboration has brought us closer to a sustainable approach to combat the challenges posed by these plastic particles," said Dr. Rojas.

More information: Yu Wang et al, Flowthrough Capture of Microplastics through Polyphenol‐Mediated Interfacial Interactions on Wood Sawdust, Advanced Materials (2023). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202301531

Journal information: Advanced Materials

Provided by University of British Columbia