By Michael Zakaras

Image Credit: Ketut Subiyanto on Pexels

Changing how the world operates is hard. Consider Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank (and leader of Bangladesh’s interim government), who brought the idea for lending to the poor to mainstream banks in the early 1980s. The banks challenged Yunus to prove it could work, and he did—first in one town, then five. But still, that wasn’t enough for banks to offer the loans. So, what did Yunus do? He launched the Grameen Bank, and a generation later microfinance—a system of providing small loans to people who otherwise do not have access to conventional banking—has reached every corner of the world, lifting millions out of poverty.

Having a good idea—even with proof that it works—does not guarantee adoption. Shifting what people consider “normal” takes persistence, creativity, storytelling, and perhaps above all, a community of aligned partners who learn and build together to drive momentum and adoption. In early August, such a community gathered in the United Kingdom for the third installment of the Oxford Symposium on Employee Ownership. People joined from more than 15 countries, representing business, government, and civil society. For two days, attendees were immersed in rich conversation and case studies to accelerate a good idea—employee ownership—so that it can take root.

Why Employee Ownership

So, what is employee ownership? At its heart, it’s when all employees have a significant financial stake in a company. Ideally, it involves meaningful participation in company decision-making as well. It’s different from traditional ownership structures because company profit, usually paid as dividends to shareholders, is available to employees. This money can make a transformative difference to working families—for example, to pay for education or as a home down payment.

Shifting what people consider “normal” takes persistence, creativity, storytelling, and perhaps above all, a community of aligned partners.

Employee ownership can take various forms, and it is not a new idea. In fact, some worker cooperatives have been around for half a century. Perhaps the most famous is the Mondragon Corporation, founded in 1956, a network of 95 autonomous cooperatives that dominate the economy in the Basque region in northern Spain.

But today, employee ownership is gaining attention. Why? First, people are deeply concerned about rising levels of economic inequality—and they understand the potential for employee ownership of businesses to reverse rising inequality by giving workers avenues to grow wealth and assets over time. If just 10 percent of every US business were employee-owned, the wealth share of the poorest 50 percent would more than double, as would the median wealth of Black households.

Another reason is demographic: many members of the so-called “baby boomer” generation will be retiring over the next decade, and will be looking to sell companies they own. Linking employee ownership to succession planning offers the opportunity to convert millions of businesses to a more equitable ownership structure.

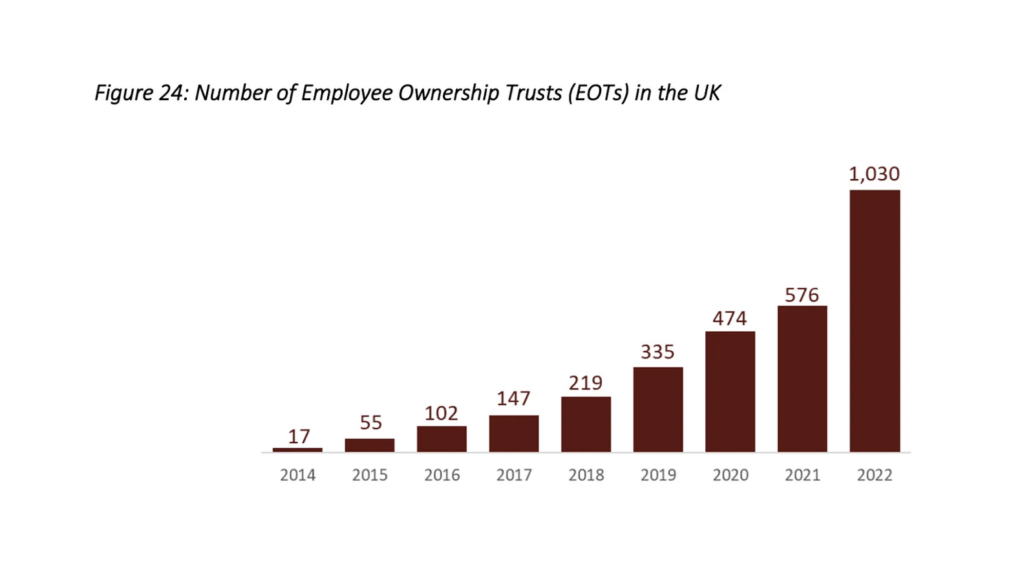

Will employee ownership fill this gap? It depends on where you look. In the United Kingdom, the data are encouraging. The number of employee-owned businesses has grown tenfold since 2017, and the rate of growth continues to accelerate, with a 40 percent increase between 2022 and 2023. This is in part because of the simplicity of the UK tax code: when you sell to an employee ownership trust, a form of business in which the business is a trust operated in the benefit of workers, you are fully exempt from capital gains tax. The trust model safeguards the workers’ ownership of a firm in perpetuity.

If just 10 percent of every US business were employee-owned, the wealth share of the poorest 50 percent would more than double.

In the United States, however, the number of employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs)—the dominant US employee ownership form involving more than 10 million Americans—has flatlined since 2014 at about 6,500 businesses, in part because tax benefits are less significant and more complex. ESOPs are being bought (including by private equity) at about the same rate as they are being created, roughly 260 a year. Worker co-ops in the United States are growing, but from a much lower base: just hundreds of total businesses and roughly 10,000 worker-owners.

Employee ownership trusts are starting to emerge in the United States as a third form, but the overall numbers are discouraging for advocates. By contrast, as the graph below illustrates, the United Kingdom’s growth pattern is stunning:

Against that backdrop, the community gathered in Oxford to ask: How do we move employee ownership from the periphery to the mainstream across more countries? How do we simulate the kind of meteoric rise we are seeing in the United Kingdom in other places?

Learning from Peers

Making the case for the high-level benefits of employee ownership continues to be a priority, attendees agreed. Employee-owned businesses are more profitable and productive. This is, in part, why employee-owners have higher wages on average. They also benefit from significantly better job stability. During COVID, ESOPs in the United States were four times less likely to experience layoffs than non-ESOP businesses.

The conference also showed that countries share similar needs around employee ownership. For example, towns in Wales and the United States alike aim to keep profits in local communities as opposed to being exported to absentee owners in London or Silicon Valley. This kind of economic development can rebuild the middle class rather than increase the wealth divide. That suggests employee ownership could be one of those rare ideas that can garner support across the political spectrum.

In some countries, governments are starting to promote employee ownership. Canada, for instance, passed its first national legislation to encourage employee ownership in 2024. It offers an income tax exemption for the first $10 million of capital gains from sales to employee ownership trusts. At the Oxford Symposium, attendees heard directly from those involved in getting Canada’s bill across the finish line. To qualify under the new Canadian law, sellers must sell a majority (minimum of 51 percent) of the company to workers, and the trust must hold shares on behalf of all employees—current and future. But it’s only a pilot. The incentive expires in 2026. This creates an urgency to build momentum over the next 18 months and get the pilot made permanent.

Jon Shell of Toronto-based Social Capital Partners walked through the ups and downs of passing the legislation over two years. He shared how disappointing the first draft was—so much so, that he and his team felt it would be worse than none. But they persisted through better drafts, benefiting from an internal public sector champion who kept the issue front and center.

Representatives from other countries like Slovenia and Denmark, where efforts are underway to create tax incentives with an emphasis on democratic governance, were paying especially close attention.

Not everything at the symposium centered around policy. Participants shared stories that speak to the personal nature of this work. For example, Dan Kenary, founder of Harpoon Brewery in Massachusetts, described the day the employee ownership announcement was made at an all-staff meeting. “I want you to meet the new owners of the company,” he said before telling them to shake hands with the people to their left and right.

But Dan’s story wasn’t all roses. The brewery transitioned in 2014, which coincided with an explosion of new craft breweries eating steadily into the company’s market share. Not all the founding partners were aligned on the employee ownership transition, which complicated the financing and meant that the company continues to service more debt today than it would have otherwise.

It was refreshing to hear these honest, unvarnished stories—it is important to understand the real challenges of company owners and policy advocates.

Several sessions got into the weeds of counteracting the potential abuses of tax measures, and best practices for achieving fairness in corporate valuations—which obviously matters a great deal to both sellers (who want to get as much as they can) and buyers (who don’t want to overpay). There’s also a real risk of bad actors, leading to overregulation and lost political support, so the conversation emphasized the importance of diligent self-policing and establishing sector-wide best practices.

Overcoming Challenges Together

The three most significant challenges that emerged across the symposium were financing transitions, the complexity of transitions, and building public awareness. Let’s start with the money. If employees are going to buy their company, they need to finance that purchase, ideally without getting saddled with too much debt.

Seller financing is a common way to facilitate sales. With seller financing, the current business owners agree to a long-term, multiyear payment plan with workers who repay the loan via future company cash flow. But not all retiring business owners can afford to wait as many as seven to 10 years to get their full payout. One solution is to provide employee-led buyout funds, essentially pools of capital that can make the purchases up front. An example is Apis & Heritage Capital Partners, which will soon invest in its seventh business transition. We need dozens of funds like that.

A second major challenge is transition complexity. This complexity involves not only the sale itself (including the valuation and financing) but also governance and decision-making post-sale. When there is outside support for new worker-owners before, during, and after the transition, it makes employee ownership more appealing and less scary. In the United States, nonprofits like Project Equity take on this role, but more support is needed.

An added layer of complexity is that the ESOP is categorized by law as a retirement benefit, subject to regulatory oversight by the US Department of Labor (DOL). This is clunky at best. Presently, DOL has a seven-year period in which it can adjust the valuation of a business. This introduces deep uncertainty into the transition process, especially for those managing buyout funds. Industry leaders like Jim Bonham of the ESOP Association are pushing to adjust this seven-year window. More than one person in Oxford felt strongly that “complexity overhangs” were the main barrier to US growth.

The final challenge symposium goers named was the need to popularize employee ownership so that more owners consider selling companies to their workers. This means continuing to collect and share the data and policy advocacy; and briefing lawyers, accountants, tax professionals, and advisors to current owners on the benefits of employee ownership. When business owners’ advisors express skepticism about employee ownership, it can stop the owner’s sale of the company to workers.

We have a fantastic idea and many powerful ingredients, but we need to act as producers to bring all the parts together into a cohesive whole

A Truly Global Learning Community

Over two days in Oxford, 120 people participated in what might be called field building with a deep spirit of mutualism and generosity—and a desire to create a tide that lifts all boats. That means not protecting intellectual property but rather giving it away. After all, the goal is replication. For example, a Northern Ireland business owner noticed that both Scotland and Wales were ahead—nearly 300 employee ownership trusts in Scotland, 63 in Wales, just a handful in Northern Ireland. He asked, “What can I do about that?”

Woven throughout was this commitment to the collective good. This work is gaining momentum, especially in Europe. There’s a window of opportunity with the enormous transition of wealth upcoming. As Campbell McDonald, the CEO of the UK think tank Ownership at Work predicted, “We are on the cusp of something big.”

While demand for employee ownership seems to be growing in the United States, with new organizations like Ownership Capital Lab and Common Trust popping up—and major networks like Ashoka and the Aspen Institute ramping up participation—most at the symposium would acknowledge that growth is still slower than desired.

Still, all must play a part in accelerating it. McDonald likened the work ahead to making a film. As he put it, we have a fantastic idea and many powerful ingredients, but we need to act as producers to bring all the parts together into a cohesive whole.

This conference was the third (and largest) installment of the Oxford Symposium on Employee Ownership, organized in large part by Jim Bonham of the Employee Ownership Foundation, Graeme Nuttall of the Employee Ownership Association, and John Hoffmire of the University of Oxford.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers. Donate

Related Posts

Maximillian Alvarez -- February 27, 2024

Just Transition for Auto Workers: The Answer to Auto’s Race to the Bottom

Jeremy Brecher -- October 05, 2023

Building Global Labor Solidarity: Where We Are Today (Early 2024)

Kim Scipes -- April 16, 2024

Shawn Fain On Class Struggle, Union Wins, And The Road Ahead For UAW

Shawn Fain -- September 13, 2024

Against Productivism

Tom Wetzel -- July 19, 2024

DonateFacebookTwitterRedditEmail

Michael Zakaras is the director of US Programs at Ashoka, the world’s largest network of social entrepreneurs.