In the 1960s she would have been celebrated by the counterculture – but a decade earlier, Rosaleen Norton was shunned and mocked

Brigid Delaney THE GUARDIAN

Mon 8 Feb 2021 16.30 GMT

They didn’t quite burn witches in Australia in the 1940s and 50s, but they didn’t make it easy for them either.

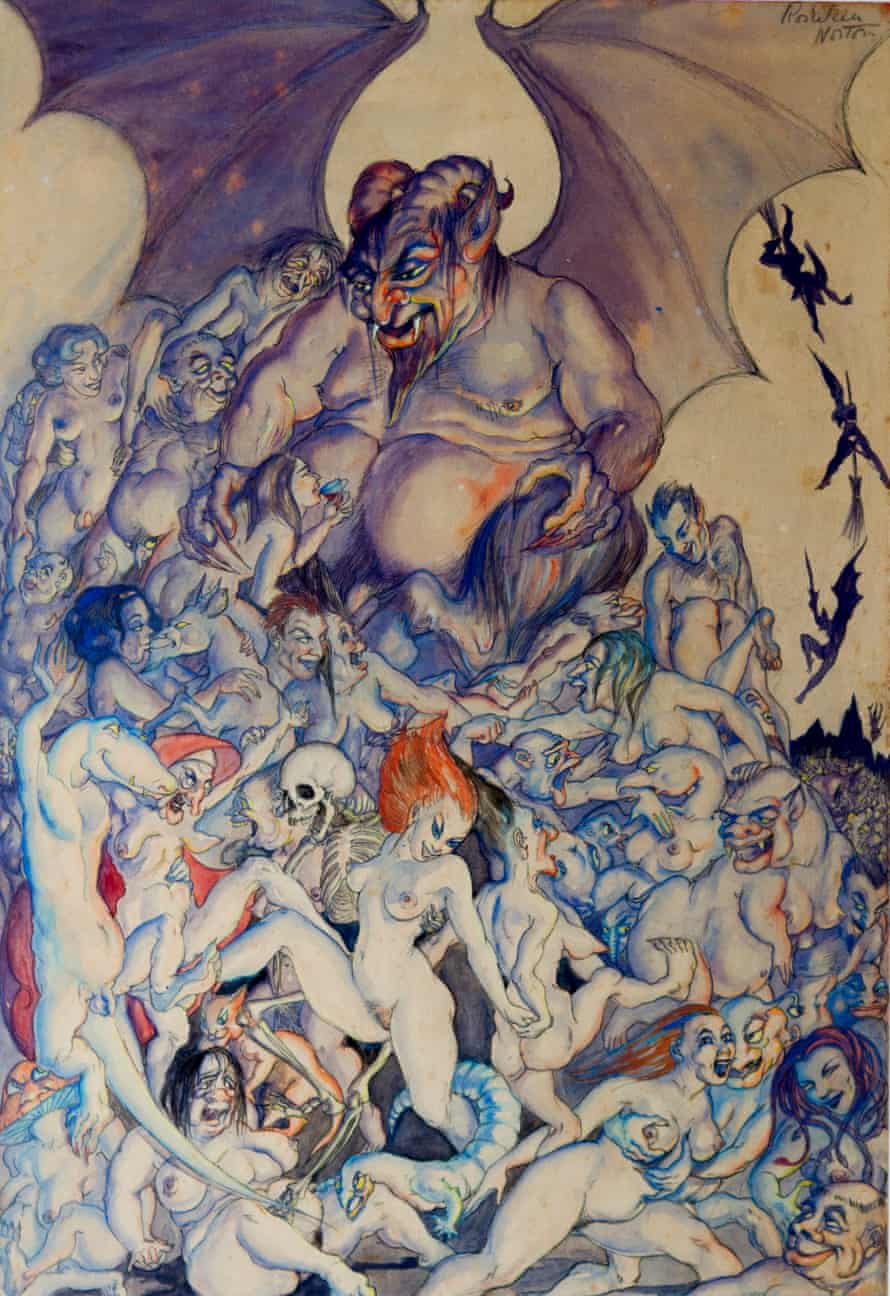

Take Rosaleen Norton, an artist and self-identified witch who the tabloids called “the witch of Kings Cross”. She was repeatedly arrested, had her artwork burned and was shunned and mocked by society.

Norton eked out a modest living selling her art, and putting spells and hexes on people. Her story has been captured in a new documentary, released online on Tuesday.

Norton, who lived in Kings Cross in the postwar years until her death in 1979, had been fascinated with the occult since she was a child.

Ban on Aleister Crowley lecture at Oxford University – archive, 1930

Aged 23 and living away from her conservative family in a variety of lodgings and squats in the seedy Sydney suburb, she began to practise trance magic and, later, sex magic. The former involved invoking spells, rituals and taking substances with the aim of achieving a higher form of consciousness; the latter was popularised by the British occultist Aleister Crowley and involved having sex with multiple partners that invoked rituals similar to Tantra.

The fascinating story of Norton’s life may have been lost had it not been for the commitment of Sonia Bible to bring it to the screen.

Made on a shoestring budget, and largely crowd- and self-funded, the documentary is a labour of love. The film-maker managed to track down several of Norton’s contemporaries before they died, and sourced diaries and artworks that were in private hands; she melds the historical documents with dramatic recreations (Norton is played by Kate Elizabeth Laxton).

Film-maker Sonia Bible says the woman dubbed the ‘witch of Kings Cross’ lived life on her terms and in her 60s was still dropping acid and making art

“When I started making the film, I knew this story was on the edge of living memory,” Bible says. “This would be the last film on the late 50s, because the people have died. The oral history of people who were there – that has gone now.”

She came across Norton’s story in the tabloid papers, while researching 2011’s Recipe for Murder – another documentary set in postwar Sydney.

“It was a time of great social change,” Bible says. “A dark noir time before pointy cars and rock’n’roll, but in the lead-up to the counterculture.

All her life, Norton combined her interest in the occult with art. Her paintings, some of which were seized by police and burned, could loosely be defined as esoteric: canvases often filled with hectic images of women embracing the Greek god Pan, snakes and horned demons.

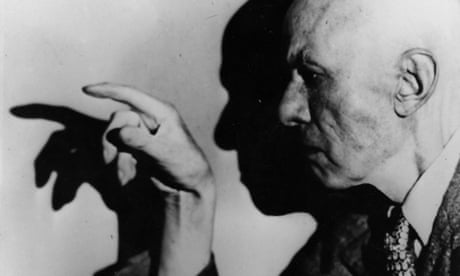

Australia in the postwar years was almost 90% Christian, and Norton was made a target for her beliefs. Surveillance and raids from the vice squad, and seizure of her work, criminalised her, and turned her into a notorious and shocking tabloid figure. One of her sex magic partners, the celebrated Sydney Symphony Orchestra conductor Sir Eugene Goossens, was forced to flee Australia when his luggage at Sydney airport was found to contain pornography. The pair each suffered in their own way for transgressing the strict moral boundaries of the time.

“There was a rapid change in relationships between men and women, social conventions and politics,” Bible says. Right now we are also living in a time of great change, but when you are in it, you can’t analyse it.”

Photograph: News Ltd

Part of the tragedy of Norton’s story is that she was born too soon – in 1917. If she were alive now, there would be a whole community of witches to connect with on TikTok – but even being born 10 years later would have made a difference, according to Bible.

“If she had been launching herself in the 1960s, with the counterculture and feminism in full swing, she would have been like Brett Whiteley … She was at the vanguard and she did have an impact and inspired people. Young people went up to the Cross looking for her.”

But even though Norton’s life was hard, Bible cautions about viewing her with pity.

“She lived the life she wanted. She didn’t value money. She was very happy. She had her art and her religion. She lived life on her own terms and towards the end she had a flat in Kings Cross, given to her by the church.

“People felt sorry for her, this old woman living in the Cross with her cats. But in her 60s she was dropping acid and still making art. She was very happy.”

• The Witch of Kings Cross releases worldwide on 9 February on Amazon, iTunes, Vimeo and GooglePlay; it will be in selected cinemas from 11 February