Aaron Copland: Left Populist Composer

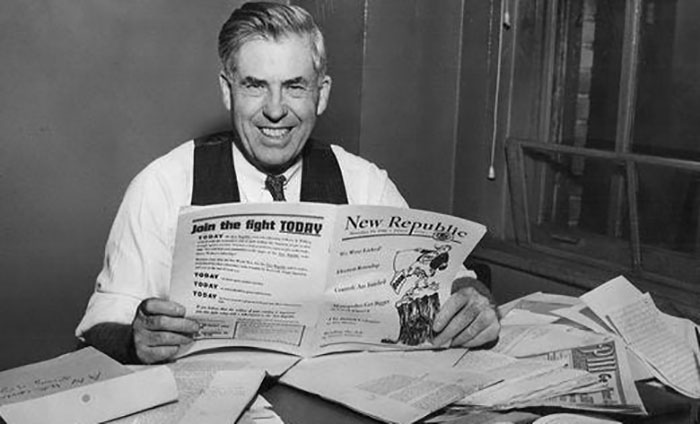

Aaron Copland (Photo Credit: Erich Auerbach/Getty Images 1965)

Aaron Copland (Photo Credit: Erich Auerbach/Getty Images 1965)

In the mid-20th century (say, 1930-1970), orchestral music played a much more prominent role in national culture–both in the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.–than it does today. In part, the advent of radio in the 1920s could bring live concerts to a mass audience. Radio networks attracted top-notch musicians and conductors; the NBC Symphony Orchestra, led at different times by super-stars such as Toscanini and Stokowski, had millions of listeners weekly–listeners who would become familiar with Copland as well as Sibelius, Shostakovich and Tchaikovsky.

With the Great Depression (ca. 1929-1942), the majority of Americans, disgusted with the stock speculations of super-rich investors which had led to massive unemployment and poverty, was to some extent radicalized–and that was reflected in many of FDR’s New Deal programs. The working person, whether farmer or factory worker, was appreciated with a renewed respect: honest labor, not stock-manipulation. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939), about the desperate plight of a family of displaced tenant-farmers who end up half-starving as fruit-pickers in California, became an instant classic (and remains so today).

These economic hardships, brought on by the panic-stricken collapse of inflated share-values, affected almost everyone–and many turned, for the first time, to promoting labor rights or even socialist politics. The famous General Motors sit-down strikes (1936-1937), which paralyzed operations at several plants for over 40 days, made the United Auto Workers (UAW) a force to be reckoned with.

In the Thirties, painters like Norman Rockwell and Thomas Hart Benton celebrated the pride of honest working people who were joining in the common cause of economic democracy. In 1944, President Roosevelt accordingly called for just such an “economic bill of rights,” which would supplement the guarantee of liberties of the original Bill of Rights (appended to the Constitution at the insistence of Thomas Jefferson).

How did all these events affect musical composition? In the Twenties, strongly influenced by Paris-based modernists such as Stravinsky, young Americans who had studied there wrote in a daring, somewhat dissident style (epater le bourgeois!). Aside from George Gershwin, who had written a jazz-inflected piano concerto as well as a lyrical, humanistic opera about a slave couple (Porgy and Bess), the young Aaron Copland (1900-1990) wrote avant-garde, jarring and startling pieces such as his Symphonic Ode and Organ Symphony.

All this was to change after The Crash. A beleaguered, out-of-work working-class forged a strong, genuine sense of class solidarity (and pride). Unions were once again doing battle, and winning (although unemployment remained in high double-digits through the Thirties). Copland, a socialist like so many artists and writers of that time, attained meteoric fame when he created his own, unique, folk-populist style in contemporary orchestral music.

In the Thirties, emulating Stravinsky’s early career, he mostly wrote ballet scores–in his case, for famed choreographers such as Agnes deMille and Martha Graham. Using ingenious orchestration and folk-like dance rhythms, Copland achieved what some still regard as masterpieces: Rodeo (the cowboy’s sense of freedom on the open plains), Billy the Kid (the colorful exploits of the misunderstood, free-spirited “outlaw”) and, above all, Appalachian Spring (the joys of newlyweds beginning a new life on a rustic Pennsylvania homestead). Unmistakably American-populist, these lively pieces proved exceedingly popular: brilliant yet spare orchestration, pastoral serenity and rollicking exuberance, these works sound as fresh and optimistic today as when they were written. The populism was of the left, because, like some Soviet works of the same period, these works celebrated those who, figuratively speaking, made a livelihood, in rural-pastoral simplicity without being capitalists.

With Pearl Harbor (December 1941), and an American commitment to defeating the fascist Axis powers, Copland remained the leading contemporary American composer, and wrote his deceptively simple yet rousingly affirming Fanfare for the Common Man (1942). While other composers were commissioned to write fanfares, none achieved anything like the popularity of Copland’s piece. In the immediate post-war period, he even incorporated it–much as Beethoven incorporated the “Ode to Joy” in the finale of his universal-humanistic Symphony no. 9–into the finale of his Third Symphony (1946). The symphony’s wonderful passages of pensive lyricism, countered by an unstoppable, almost delirious exuberance and optimism, no doubt reflected the popular sentiment of post-war triumphalism and renewed hope. The Symphony retains its freshness of brilliant moods and textures, but in hindsight seems to me somewhat untimely given the shadows of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (One might add that, back then, ethnocentric Americans readily accepted the dehumanizing stereotypes of what the late Edward Said called “Orientalism”).

In the years that followed, Copland continued to reconcile his American populism with a left-socialist orientation. For the second anniversary of the founding of the United Nations, he wrote a somber, almost hymn-like, orchestral piece called Preamble to a Solemn Occasion, which served as powerful musical accompaniment to an international reaffirmation of the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (It is well worth reading about the sad fate of U.S. diplomat Alger Hiss, a key figure in the founding of the UN, who was framed as a Soviet spy and sent to prison.)

During that post-war period of anti-Communist hysteria, Copland, like so many artists and writers who had joined socialist organizations, actively supported the 1948 presidential candidacy of ultra-leftist Henry Wallace on an alternative Progressive Party ticket. Meanwhile, he wrote one of his finest orchestral pieces, A Lincoln Portrait, which daringly included eloquent passages from some of Lincoln’s most moving, almost-radical speeches extolling a kind of democratic socialism. This piece, wonderfully lyrical and inspirational, has been recorded and narrated by countless speakers, ranging from Maya Angelou to Gore Vidal.

Conservatives insisted that the piece, originally scheduled to be performed at Eisenhower’s presidential inauguration in 1953, be dropped from the program. Copland was blacklisted, and shortly thereafter ordered to appear before Sen. Joe McCarthy’s red-baiting internal security subcommittee. Without naming names, Copland managed to survive the brief ordeal with great aplomb. Later, Copland recalled that a Foreign Service official recounted to him that when the piece was performed in Venezuela, ending with Lincoln’s words that “government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth,” the massive audience went wild with enthusiasm, started public demonstrations against the repressive dictator Jimenez, and successfully deposed him soon thereafter.

The left-populist compositions of Aaron Copland in no way compromised his high artistic standards of originality, melodic inventiveness, and ingenious orchestration. The works I have mentioned have by now been recorded dozens of times by dozens of orchestras, even up to the present. Although his optimistic worldview–of freedom and dignity, economic fairness and equal rights, and the triumphant exultation of the defiant human spirit–may seem sadly anachronistic, the overflowing freshness and vitality of his music even now offers a powerfully felt experience of humanity vigorously experiencing the joy of being free and alive