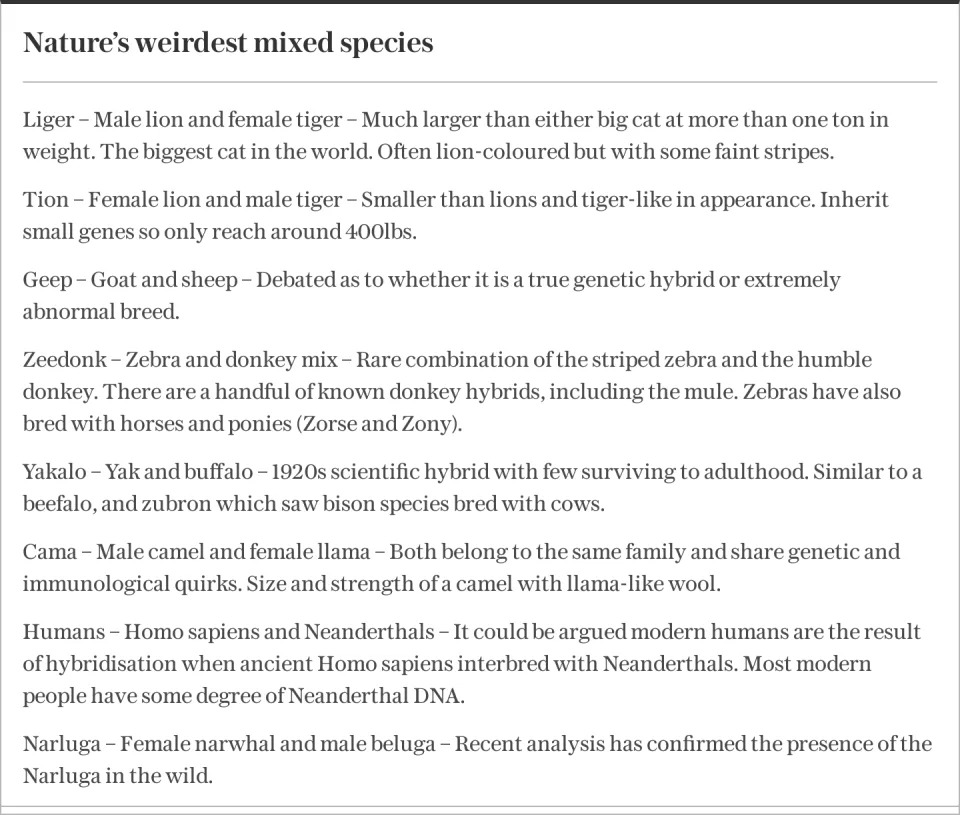

Genomic analysis reveals true origin of South America’s canids

The continent’s diverse species all evolved rapidly from a single ancestral population, study shows

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: THE MANED WOLF, THE TALLEST AND LONGEST-LEGGED CANID IN SOUTH AMERICA, IS MOST CLOSELY RELATED TO THE SHORTEST, THE BUSH DOG, RESEARCHERS FOUND. view more

CREDIT: ROGÉRIO CUNHA DE PAULA

South America has more canid species than any place on Earth, and a surprising new UCLA-led genomic analysis shows that all these doglike animals evolved from a single species that entered the continent just 3.5 million to 4 million years ago. Scientists had long assumed that these diverse species sprang from multiple ancestors.

Even more surprising? The tallest and shortest species are the most closely related.

Some of the key genetic mutations that led to the rapid emergence of extreme variations in the height, size and diet of South American canids have been introduced artificially through selective breeding over the past few thousand years to produce the staggering diversity seen in a more familiar canid: the domestic dog.

The research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows how quickly new carnivore species can evolve and spread in environments lacking competition and offers guidance for the conservation of threatened and endangered South American canids.

Ten species within the dog and wolf family, known as canids, live in South America today. Seven are foxes and three are more unusual: the short-eared dog, bush dog and maned wolf.

For years, scientists had a theory about how South America had become home to so many types of canids. The continent had very few placental mammals, and no ancestral canids, until the volcanic strip of land known as the Isthmus of Panama rose above level sea some 3 million years ago, allowing the free movement of animals between continents. That’s a short window for so many species to evolve from a single ancestor, so scientists assumed that multiple canid species had entered through the isthmus at different times, giving rise to existing and now-extinct species.

To learn how these species were related and how long ago and by what genetic mechanisms they diverged, UCLA doctoral student Daniel Chavez, now a postdoctoral researcher at Arizona State University, and UCLA evolutionary biology professor Robert Wayne sequenced 31 genomes encompassing all 10 extant South American canid species. They traced the evolutionary relationships between the species by studying the locations, quantity and types of genetic mutations among them.

Surprisingly, the genetic data pointed to a single ancestral canid population that arrived between 3.5 million and 3.9 million years ago — before the isthmus had fully risen — and comprised approximately 11,600 individuals. The researchers said those ancestors must have made their way south through the newly developing Panama corridor, then just a narrow strip of savannah that generally was not navigable by large populations.

“We found that all extant canids came from a single invasion that entered South America east of the Andes,” Chavez said. “By 1 million years ago, there were already a lot of canid species, but they weren’t very genetically distinct because of gene flow, which happens when populations can interbreed easily.”

These species soon spread all over South America, including the thin strip of land west of the Andes, adapting to different environments and becoming more genetically distinct. Today’s 10 species, the researchers found, all emerged between 1 million and 3 million years ago.

They also discovered that the maned wolf, the tallest and most long-legged canid in South America and the only one that eats mostly fruit, and the shortest, the bush dog, which depends even more on meat than wolves and African wild dogs, are the most closely related. Changes in the gene that regulates leg length are responsible for the height difference.

“There were also many other now-extinct species of hypercarnivores related to the bush dog,” Chavez said. “Maybe they were bigger in size, so to compete, the ancestors of the bush dog got smaller while the maned wolf got taller and eventually stopped competing for meat.”

Such rapid and extreme speciation through natural selection resembles the vast differentiation among domestic dogs, which occurred quickly through artificial selection by humans.

“South American canids are the domestic dog of the wild animal kingdom in that they vary hugely in leg length and diet, and these changes happened very fast, on the order of 1 to 2 million years,” Wayne said. “It’s a natural parallel to what we’ve done to dogs. This all happened because South America was empty of this kind of carnivore. There was lots of prey and no large or medium-sized carnivores to compete with. In this empty niche, nature allowed such fast radiation.”

The findings have also illuminated relationships between the species and identified genes that can help efforts to save species threatened by habitat loss and climate change.

“Darwin’s fox, which currently survives only on one island off the coast of Chile and very small regions on the mainland, is a good example of the need for conservation,” Wayne said. “We’ve proved at genome level great differences in variation among species, with the most endangered having very low levels of variation and genes that can be harmful. We can rescue small populations through thoughtful captive breeding programs.”

JOURNAL

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences