By AFP

December 12, 2024

Rebel fighters said they found a drug factory linked to Maher al-Assad, widely accused of being the power behind the lucrative captagon trade

Dave CLARK

The dramatic collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime has thrown light into the dark corners of his rule, including the industrial-scale export of the banned drug captagon.

Victorious Islamist-led fighters have seized military bases and distribution hubs for the amphetamine-type stimulant, which has flooded the black market across the Middle East.

Led by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group, the rebels say they found a vast haul of drugs and vowed to destroy them.

On Wednesday, HTS fighters allowed Afp journalists into a warehouse at a quarry on the outskirts of Damascus, where captagon pills were concealed inside electrical components for export.

“After we entered and did a sweep, and we found that this is a factory for Maher al-Assad and his partner Amer Khiti,” said black-masked fighter Abu Malek al-Shami.

– Household appliances –

Maher al-Assad was a military commander and the deposed strongman’s brother, now presumed on the run. He is widely accused of being the power behind the lucrative captagon trade.

Syrian politician Khiti was placed under sanction in 2023 by the British government, which said he “controls multiple businesses in Syria which facilitate the production and smuggling of drugs”.

In a cavernous garage beneath the warehouse and loading bays, thousands of dusty beige captagon pills were packed into the copper coils of brand new household voltage stabilisers.

“We found a large number of devices that were stuffed with packages of captagon pills meant to be smuggled out of the country. It’s a huge quantity. It’s impossible to tell,” Shami said.

Above, in the warehouse, crates of cardboard boxes stood ready to allow the traffickers to disguise their cargo as pallet-loads of standard goods, alongside sacks and sacks of caustic soda.

Caustic soda, or sodium hydroxide, is a key ingredient in the production of methamphetamine, another stimulant.

Assad fell at the weekend to a lightning HTS offensive, but the revenue from selling captagon propped up Assad’s government throughout Syria’s 13 years of civil war.

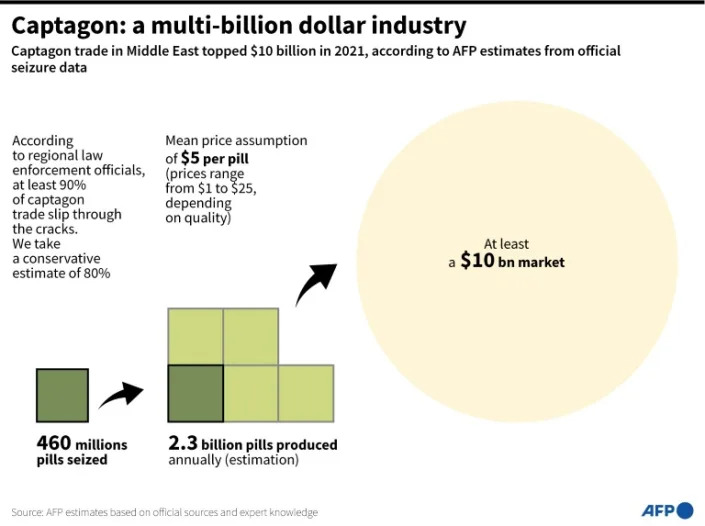

Captagon turned Syria into the world’s largest narco state. It became by far Syria’s biggest export, dwarfing all its legal exports put together, according to estimates drawn from official data by AFP during a 2022 investigation.

Experts — like the author of a July report from the Carnegie Middle East Center — also believe that Assad used the threat of drug-fuelled unrest to put pressure on Arab governments.

Captagon fuelled an epidemic of drug abuse in wealthy Gulf states, even as Assad sought ways to end his diplomatic isolation among his peers, wrote Carnegie scholar Hesham Alghannam.

– ‘Huge amount, brother’ –

Assad, he wrote, “leveraged captagon trafficking as a means of exerting pressure on the Gulf states, notably Saudi Arabia, to reintegrate Syria into the Arab world”, which it did in 2023 when it rejoined the Arab League bloc.

The caustic soda at the warehouse, in the Damascus suburbs, was supplied from Saudi Arabia, according to labelling on the sacks.

The warehouse haul was massive, but smaller and still impressive stashes of captagon have also turned up in military facilities associated with units under Maher Assad’s command.

Journalists from AFP this week found a bonfire of captagon pills on the grounds of the Mazzeh air base, now in the hands of HTS fighters who descended on the capital Damascus from the north.

Behind the smouldering heap, in a ransacked air force building, more captagon lay alongside other illicit exports, including off-brand Viagra impotence remedies and poorly-forged $100 bills.

“As we entered the area we found a huge quantity of captagon. So we destroyed it and burned it. It’s a huge amount, brother,” said an HTS fighter using the nom de guerre “Khattab”.

“We destroyed and burned it because it’s harmful to people. It harms nature and people and humans.”

Khattab also stressed that HTS, which has formed a transitional government to replace the collapsed administration, does not want to harm its neighbours by exporting the drug — a trade worth billions of dollars.

Story by Alex Croft

• 12/13/2024 • THE INDEPENDENT

As the dust settles on the fragments of Bashar al-Assad’s collapsed Syrian dictatorship, the truth about a mass drug empire believed to have brought huge profits to the former regime is being uncovered among the ashes.

The Assad family was long accused by Washington and other international actors of profiteering from the production and sale of captagon, an addictive amphetamine-like stimulant which swept across the Middle East and became known as “poor-man’s cocaine”.

The regime consistently denied links to the global captagon trade, which experts say is worth billions of dollars a year. A stimulant first produced in 1960s Germany to help treat attention deficit disorders and narcolepsy has swept the Middle East across the past decade.

It was discontinued but an illicit version of the drug known as "poor man's cocaine" continued to be produced in eastern Europe and later in the Arab world, becoming prominent in the conflict that erupted in Syria following anti-government protests in 2011.

It staves off sleep and hunger. It has been banned in many countries including the U.S. and can have harmful side effects. Its prevalence has led to growing drug abuse in Gulf Arab states.

Syrian members of the rebel group inspecting electrical components that were used to hide amphetamine pills (AP)

Now that the Assad family has been ousted following a lightning insurgency led by former al-Qaeda affiliate Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the scale of the trade in captagon is becoming clear.

In the city of Douma, 10 kilometres northeast of Syria’s capital of Damascus, warehouses storing thousands of captagon pills have been unearthed by the rebels scouring areas once controlled by the Assad regime and its allies. The warehouse, according to experts, may be one of the biggest captagon labs ever seen.

Pills were found hidden in furniture, fruit, decorative pebbles and voltage stabilisers. Many had a double crescent logo stamped on them, marking them as captagon pills.

Amphetamine pills, known as Captagon, hidden inside an electrical component at a warehouse where the drug was manufactured (AP)

Inside the warehouse, a pill-press was found along with dozens of barrels holding the various chemicals required to produce captagon. The chemicals came from various countries including the UK, China and India.

The leadership of Syria made an annual profit from captagon of around $2.4 billion, according to Caroline Rose, the director of the New-York-based New Lines Institute Captagon Trade Project. An investigation by AFP news agency found that captagon had become Syria’s largest export, dwarfing its legal businesses.

Ms Rose, whose organisation tracks all publicly recorded captagon seizures and lab raids, said the site appeared to be one of the biggest captagon labs that has been found.

"It’s very possible that it's the biggest one that existed in regime-held Syria," she said.

Captagon helped to prop up Assad’s war effort to the tune of $2.4 billion per year (AP)

Last year, the US Treasury sanctioned a number of Syrians closely associated with the Assad regime for their alleged involvement captagon trade.

“The Syrian regime and its allies have increasingly embraced the production and trafficking of captagon to generate hard currency, estimated by some to be in the billions of dollars,” the Treasury said.

More videos

France24 (Video)Syrians celebrate the demise of Assad's regime as thousands freed from prison

8:15

France24 (Video)Syrian rebels discover large-scale drug factories

2:05

Among those sanctioned were two cousins of Bashar al-Assad and Khalid Qaddour, a close associate of Maher al-Assad, brother of Bashar, who was described as a “key drug producer and facilitator” of captagon production in Syria.

In the days since Assad's fall, rebel fighters say they have found several sites across the country where the drug was produced and prepared for export.

They have sometimes set fire to the pills or poured them down drains, according to videos shared online by accounts affiliated with them.

Ms Rose noted that her organisation tracked all publicly recorded captagon seizures and lab raids.

"Up until the regime fell, there was not a single incident of a laboratory seizure on the database in regime-held territories," she said.

Speaking in front of a crowd of supporters inside the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, rebel leader Abu Mohammad al-Golani told supporters according to AFP: “Syria has become the biggest producer of Captagon on Earth, and today, Syria is going to be purified by the grace of God.”

Reuters contributed to this report

The Independent stands for many things, often uniquely so. It stands independent of political party allegiance, and makes its own mind up on the issues of the day. The Independent has always been committed to challenge and debate. It launched in 1986 to create a new voice and in that time has run campaigns for issues ranging from the legalisation of marijuana to the Final Say Brexit petition.

After the fall of the al-Assad regime in Syria, large stockpiles of the illicit drug captagon have reportedly been uncovered.

The stockpiles, found by Syrian rebels, are believed to be linked to al-Assad military headquarters, implicating the fallen regime in the drug’s manufacture and distribution.

But as we’ll see, captagon was once a pharmaceutical drug, similar to some of the legally available stimulants we still use today for conditions including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Captagon was once a pharmaceutical

Captagon is the original brand name of an old synthetic pharmaceutical stimulant originally made in Germany in the 1960s. It was an alternative to amphetamine and methamphetamine, which were both used as medicines at the time.

The drug has the active ingredient fenethylline and was initially marketed for conditions including ADHD and the sleeping disorder narcolepsy. It had a similar use to some of the legally available stimulants we still use today, such as dexamphetamine.

Captagon has similar effects to amphetamines. It increases dopamine in the brain, leading to feelings of wellbeing, pleasure and euphoria. It also improves focus, concentration and stamina. But it has a lot of unwanted side effects, such as low-level psychosis.

The drug was originally sold mostly in the Middle East and parts of Europe. It was available over the counter (without a prescription) in Europe for a short time before it became prescription-only.

It was approved only briefly in the United States before becoming a controlled substance in the 1980s, but was still legal for the treatment of narcolepsy in many European countries until relatively recently.

According to the International Narcotics Control Board pharmaceutical manufacture of Captagon had stopped by 2009.

The illicit trade took over

The illegally manufactured version is usually referred to as captagon (with a small c). It is sometimes called “chemical courage” because it is thought to be used by soldiers in war-torn areas of the Middle East to help give them focus and energy.

For instance, it’s been reportedly found on the bodies of Hamas soldiers during the conflict with Israel.

Its manufacture is relatively straightforward and inexpensive, making it an obvious target for the black-market drug trade.

Black-market captagon is now nearly exclusively manufactured in Syria and surrounding countries such as Lebanon. It’s mostly used in the Middle East, including recreationally in some Gulf states.

It is one of the most commonly used illicit drugs in Syria.

A recent report suggests captagon generated more than US$7.3 billion in Syria and Lebanon between 2020 and 2022 (about $2.4 billion a year).

What we know about illicit drugs generally is that any seizures or crackdowns on manufacturing or sale have a very limited impact on the drug market because another manufacturer or distributor pops up to meet demand.

So in all likelihood, given the size of the captagon market in the Middle East, these latest drug discoveries and seizures are likely to reduce manufacture only for a short time.

Adjunct Professor at the National Drug Research Institute (Melbourne based), Curtin University

Disclosure statement

Nicole Lee works as a paid consultant to the alcohol and other drug sector. She has previously been awarded grants by state and federal governments, NHMRC and other public funding bodies for alcohol and other drug research. She is a Board member of The Loop Australia.