America's nonreligious are a growing, diverse phenomenon. They really don't like organized religion

Mike Dulak grew up Catholic in Southern California, but by his teen years, he began skipping Mass and driving straight to the shore to play guitar, watch the waves and enjoy “the beauty of the morning on the beach,” he recalled. “And it felt more spiritual than any time I set foot in a church.”

Nothing has changed that view in the ensuing decades.

“Most religions are there to control people and get money from them,” said Dulak, now 76, of Rocheport, Missouri. He also cited sex abuse scandals, harming “innocent human beings,” in Catholic and Southern Baptist churches. “I can’t buy into that,” he said.

As Dulak rejects being part of a religious flock, he has plenty of company. He is a “none” — no, not that kind of nun. The kind that checks “none” when pollsters ask “What’s your religion?”

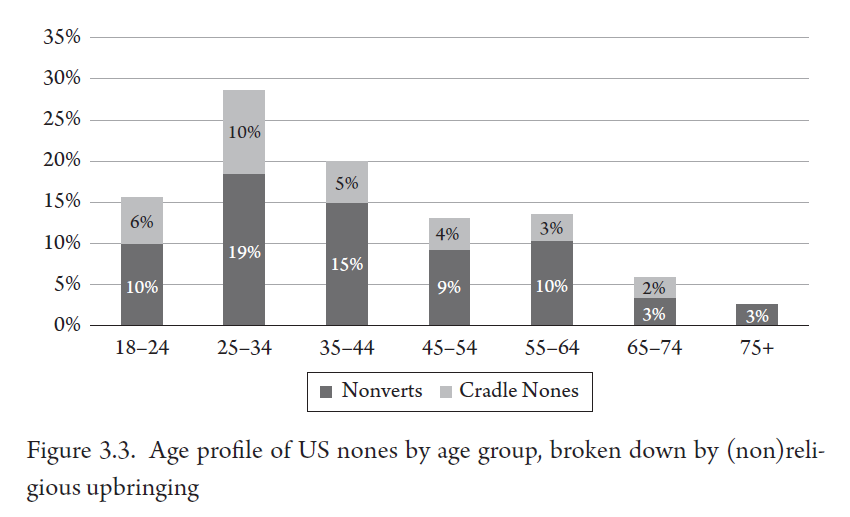

The decades-long rise of the nones — a diverse, hard-to-summarize group — is one of the most talked about phenomena in U.S. religion. The nones are reshaping America’s religious landscape as we know it.

In U.S. religion today, “the most important story without a shadow of a doubt is the unbelievable rise in the share of Americans who are nonreligious,” said Ryan Burge, a political science professor at Eastern Illinois University and author of “The Nones,” a book on the phenomenon.

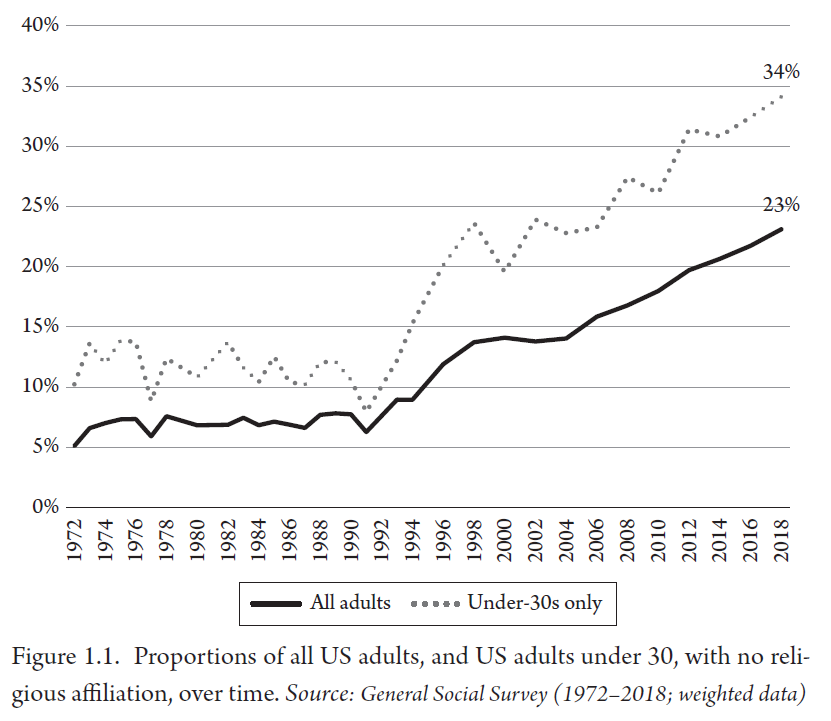

The nones account for a large portion of Americans, as shown by the 30% of U.S. adults who claim no religious affiliation in a survey by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Other major surveys say the nones have been steadily increasing for as long as three decades.

So who are they?

They’re the atheists, the agnostics, the “nothing in particular.” Many are “spiritual but not religious,” and some are neither or both. They span class, gender, age, race and ethnicity.

While the nones’ diversity splinters them into myriad subgroups, most of them have this in common:

They. Really. Don’t. Like. Organized. Religion.

Nor its leaders. Nor its politics and social stances. That’s according to a large majority of nones in the AP-NORC survey.

But they’re not just a statistic. They’re real people with unique relationships to belief and nonbelief, and the meaning of life.

They’re secular homeschoolers in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, Pittsburghers working to overcome addiction. They’re a mandolin maker in a small Missouri River town, a former evangelical disillusioned with that particular strain of American Christianity. They’re college students who found their childhood churches unpersuasive or unwelcoming.

Church “was not very good for me,” said Emma Komoroski, a University of Missouri freshman who left her childhood Catholic religion in her mid-teens. “I’m a lesbian. So that was kind of like, oh, I didn’t really fit, and people don’t like me.”

The nones also are people like Alric Jones, who cite bad experiences with organized religion that ranged from the intolerant churches of his hometown to the ministry that kept soliciting money from his devout late wife — even after Jones lost his job and income after an injury.

“If it was such a Christian organization, and she was unable to send money, they should have come to us and said, 'Is there something we can do to help you?'” said Jones, 71, of central Michigan. “They kept sending us letters saying, ‘Why aren’t you sending us money?’”

Related video: America's nonreligious have become a growing phenomenon (The Associated Press) Duration 6:35 View on Watch

Jones does believe in God and in treating others equally. "That’s my spirituality if you want to call it that.”

About 1 in 6 U.S. adults, including Jones and Dulak, is a “nothing in particular.” There are as many of them as atheists and agnostics combined (7% each).

Many embrace a range of spiritual beliefs — from God, prayer and heaven to karma, reincarnation, astrology or energy in crystals.

“They are definitely not as turned off to religion as atheists and agnostics are,” Burge said. “They practice their own type of spirituality, many of them.”

Dulak still draws inspiration from nature, and from making mandolins in the workshop next to his home.

“It feels spiritually good,” Dulak said. “It’s not a religion.”

Burge said the nones are rising as the Christian population declines, particularly the “mainline” or moderate to liberal Protestants.

The statistics show the nones are well-represented in every age group, but especially among young adults. About four in 10 of those under 30 are nones — nearly as many as say they’re Christians.

The trend was evident in interviews on the University of Missouri campus. Several students said they didn’t identify with a religion.

Mia Vogel said she likes “the foundations of a lot of religions — just love everybody, accept everybody.” But she considers herself more spiritual.

“I’m pretty into astrology. I’ve got my crystals charging up in my window right now,” she said. “Honestly, I’ll bet half of it is a total placebo. But I just like the idea that things in life can be explained by greater forces.”

One movement that exemplifies the “spiritual but not religious” ethos is the Twelve Step sobriety program, pioneered by Alcoholics Anonymous and adopted by other recovery groups. Participants turn to a “power greater than ourselves” — the God of each person’s own understanding — but they don’t share any creed.

“If you look at the religions, they have been wracked by scandals, it doesn’t matter the denomination,” said the Rev. Jay Geisler, an Episcopal priest who is spiritual advisor at the Pittsburgh Recovery Center, an addiction treatment site.

In contrast, “there’s actually a spiritual revival in the basement of many of the churches,” where recovery groups often meet, he said.

“Nobody’s fighting in those rooms, they’re not saying, ‘You’re wrong about God,’” Geisler said. The focus is on “how your life is changed.”

Scholars worry that, as people pull away from congregations and other social groups, they are losing sources of communal support.

But nones said in interviews they were happy to leave religion behind, particularly in toxic situations, and find community elsewhere.

Marjorie Logman, 75, of Aurora, Illinois, now finds community among other residents in her multigenerational apartment complex, and in her advocacy for nursing home residents. She doesn’t miss the evangelical circles she was long active in.

“The farther away I get, the freer I feel,” she said.

__

AP journalists Linley Sanders, Emily Swanson and Jessie Wardarski contributed.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

___

The poll of 1,680 adults was conducted May 11-15 using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 3.4 percentage points.

Peter Smith, The Associated Press