Alice G. Walton Senior Contributor

FORBES NWO DEEP STATE JUST KIDDING

OR AM I

FORBES THE MAGAZINE IS MORE LIBERAL

THAN ITS OWNER OR FOX BUSINESS NEWS

Face masks GETTY

As Covid-19 cases mount in several states, and the U.S. as a whole still is still posting frighteningly high numbers, some local leaders are finally requiring face masks in public. But there has been no federal level directive on the matter. Masks have been strangely politicized, while numbers of cases and hospitalizations are rising in many areas. A new paper out in the journal the Physics of Fluids helps visualize exactly why masks are important in reducing the spread, and which types of mask appear to be most effective.

"While there are a few prior studies on the effectiveness of medical-grade equipment, we don't have a lot of information about the cloth-based coverings that are most accessible to us at present," said study author Siddhartha Verma in a statement. "Our hope is that the visualizations presented in the paper help convey the rationale behind the recommendations for social distancing and using face masks."

The team used a manikin (a medical mannequin) to model coughing and sneezing. The spray was replicated using a pump of water and glycerin solution (“respiratory jets”) paired with fog machine particles (“tracer particles”) to help visualize the activity. Lasers captured the behavior of the particles as they escaped the masks through gaps or the fabric itself. The team repeated the experiment with a variety of mask types—a bandana, a mask made from a folded handkerchief using instructions from the U.S. Surgeon General, a stitched mask made of two layers of quilting cotton, and a drugstore brand cone face mask.

Most Popular In: Healthcare

New Swine Flu Virus In China Has ‘Pandemic Potential,’ Here Are 7 Reasons Why

Wearing A Mask Is A Sign Of Mutual Respect During The Coronavirus Pandemic

Regeneron’s Billionaire Cofounder Criticized After ‘All Lives Matter’ Graduation Speech

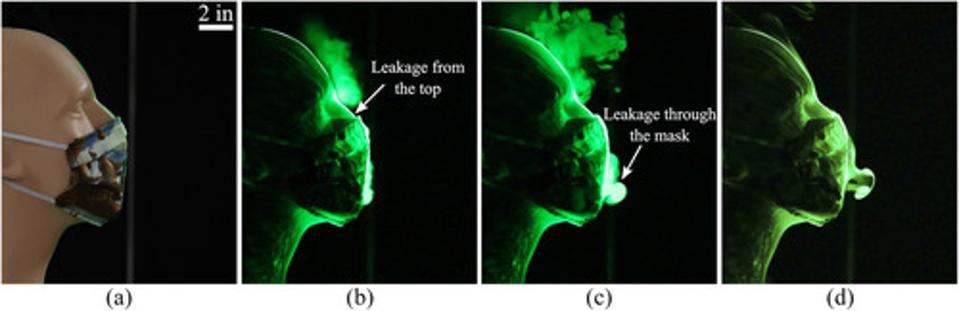

The stitched mask and store-bought masks were the most effective (see images below). The stitched mask was able “to arrest the forward motion of the tracer droplets almost completely,” the authors write. There was little leakage through the material itself—most of it came from gaps above the nose. The leakage traveled 2.5 inches on average.

Homemade mask, quilting fabric VERMA ET AL 2020

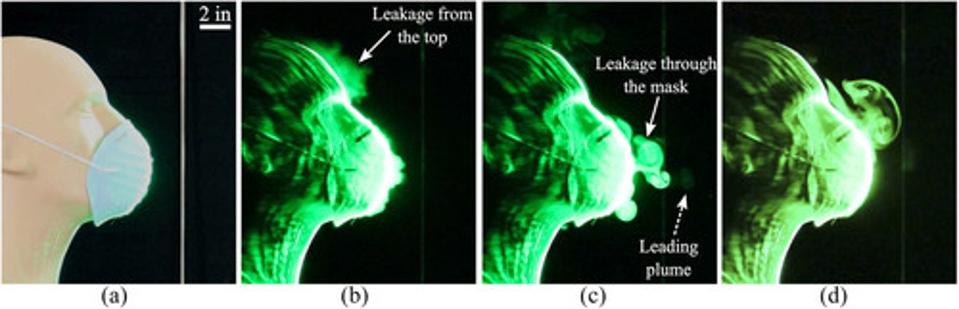

The cone mask was also quite good, though the team notes a little more leakage than the homemade mask. Jets traveled about 6 inches.

Store-bought mask. VERMA ET AL 2020

The handkerchief mask was mediocre, with an average jet distance of 1.25 feet. The team writes that “while the forward motion of the jet is impeded significantly, there is notable leakage of tracer droplets through the mask material.” Some droplets also escaped through the top of the mask. The bandana (not pictured) performed considerably worse, with average jet distance of 3.5 feet.

Handkerchief mask, constructed per US Surgeon General's instructions VERMA ET AL 2020

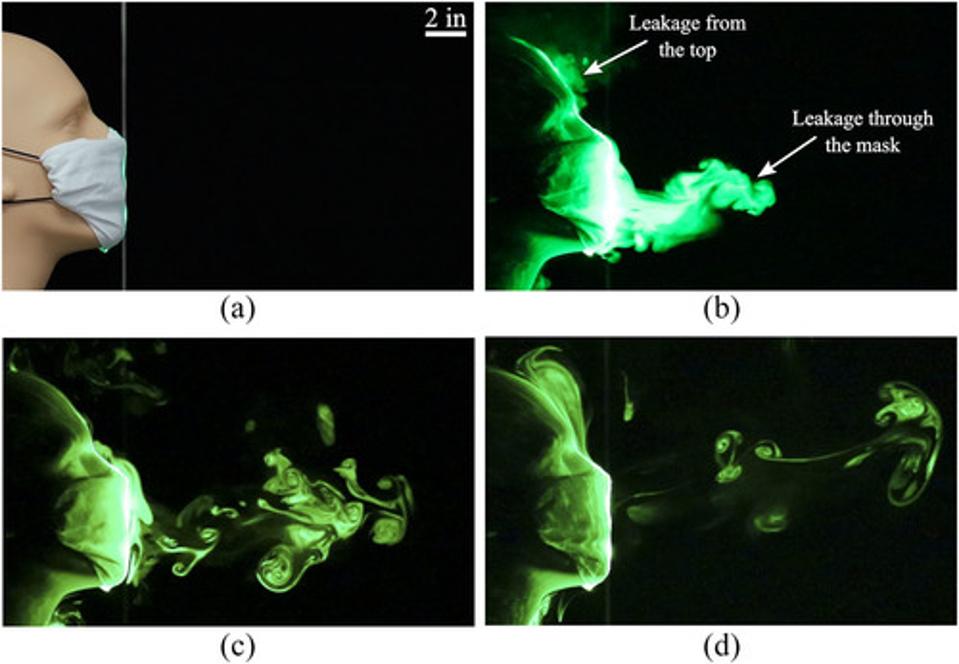

The team also looked at the spray of a cough and sneeze when the manikin was wearing nothing over its face: This, of course, spewed droplets far and wide, with particles reaching 12 feet—twice the distance that social distancing guidelines say to maintain. In fact, another study out today in the same journal analyzed the aerodynamics of droplets as they move through the air or evaporate and fall—they traveled up to 13 feet. The findings are also in line with earlier work, suggesting that droplets can linger in the air for many minutes.

It is, of course, important to point out that the new study was just a small observational study, with manikins rather than people—and the coughs and sneezes generated by the pump were simply a model of the human versions.

Still, the new research, along with previous studies, suggest that wearing a mask in public is a relatively simple and cheap way to reduce the spread of the virus. It’s not a stand-alone and it’s not foolproof, but it does seem to help. Masks, along with the other known strategies—social distancing and hand-washing—all work in concert to reduce the risk. Financial models also suggest that a mask mandate could save the economy considerably, as it might obviate the need for further lockdowns.

It’s also worth mentioning that masks are worn as much or more for other people than for yourself—that’s why everyone needs to wear one to be effective. “We have witnessed some aversion to using face masks, and hopefully the study will help convey that using masks is primarily an effort to protect the most vulnerable members of our society (i.e., the elderly, or people with underlying health conditions),” said Verma in an email. “This is crucial since current estimates suggest that one in three infected people (35%) do not show overt symptoms, and could potentially infect such vulnerable individuals inadvertently.”

These realities are all the more important as people return to work and school in the coming months, and second waves are possible, or probable. “Promoting widespread awareness of effective preventative measures is crucial,” the team concludes, “given the high likelihood of a resurgence of COVID-19 infections in the fall and winter.”

Glow-in-the-dark sneezes show best homemade face mask is quilted cotton

The stitched quilted cotton mask proved most effective, allowing droplets from the nose and mouth to travel just 2.5 inches.

With a folded handkerchief mask over the nose and mouth, droplets from coughs and sneezes traveled 1 foot, 3 inches. Photo courtesy of Florida Atlantic University College of Engineering and Computer Science

June 30 (UPI) -- To figure what types of homemade mask best prevent the spread of COVID-19, scientists at Florida Atlantic University used glycerine and laser light to illuminate the movement of droplets from coughs and sneezes.

Researchers report the distance droplets move can be cut by more than half by using a homemade mask -- from more than 8 feet, to less than 2 feet.

For the new study, published Tuesday in the journal Physics of Fluids, researchers focused on cloth-based coverings, as most other research has focused on medical-grade masks.

"Such masks have been recommended for public use by various agencies, but there are no clear guidelines on the best material or construction technique that should be used," Siddhartha Verma, lead author and an assistant professor at Florida Atlantic, told UPI in an email.

Researchers report the distance droplets move can be cut by more than half by using a homemade mask -- from more than 8 feet, to less than 2 feet.

For the new study, published Tuesday in the journal Physics of Fluids, researchers focused on cloth-based coverings, as most other research has focused on medical-grade masks.

"Such masks have been recommended for public use by various agencies, but there are no clear guidelines on the best material or construction technique that should be used," Siddhartha Verma, lead author and an assistant professor at Florida Atlantic, told UPI in an email.

RELATED Arizona, Nevada halt reopening plans; N.Y. to require air conditioning filters in malls

They found that without a mask, droplets traveled more than 8 feet -- beyond the 6 feet recommended for "social distancing." With a bandana, droplets traveled 3 feet, 7 inches. With a folded cotton handkerchief, the droplets traveled 1 foot, 3 inches. The stitched quilted cotton mask proved most effective, allowing droplets from the nose and mouth to travel just 2.5 inches.

Scientists also tested a cone mask, widely available at local pharmacies. The commercial mask allowed droplets from simulated coughs and sneezes to travel 8 inches.

For the study, researchers sprayed a solution of distilled water and glycerin through the mouth of a mannequin to create glow-in-the-dark droplet clouds resembling those produced by coughs and sneezes.

RELATED California to require face coverings in public as coronavirus cases spike

Researchers projected the glow-in-the-dark coughs and sneezes through several types of homemade masks, using cameras to measure how far the droplets traveled.

"We visualized the droplets in a sheet of laser light," said co-author Manhar Dhanak, department chair, professor and director of SeaTech at Florida Atlantic. "The droplets scatter the light and hence become visible."Researchers determined that creating a tight seal and layering material were the most important factors in creating an effective barrier.

"The effectiveness of a mask does not necessarily depend on the thread-count of the fabric," Verma said.

RELATED Flushed toilets produce clouds of virus-containing particles, simulations show

While masks are effective in reducing the risk of transmission of viral infections, Dhanak said that "given the possibility of leakage, it is important to use a combination of social distancing, mask use, hand-washing and other recommendations from healthcare professionals in order to minimize the chances of transmission."

In future studies, Verma and Dhanak plan to more closely examine leakage around the sides of different kinds of masks and how to curtail it."We are also looking into the impact of environmental conditions in a room on the spread of the droplets and wider applications of our techniques in design of barriers, shielding and air-conditioning systems in the workplace and open-plan offices," Verma said.

upi.com/7018246

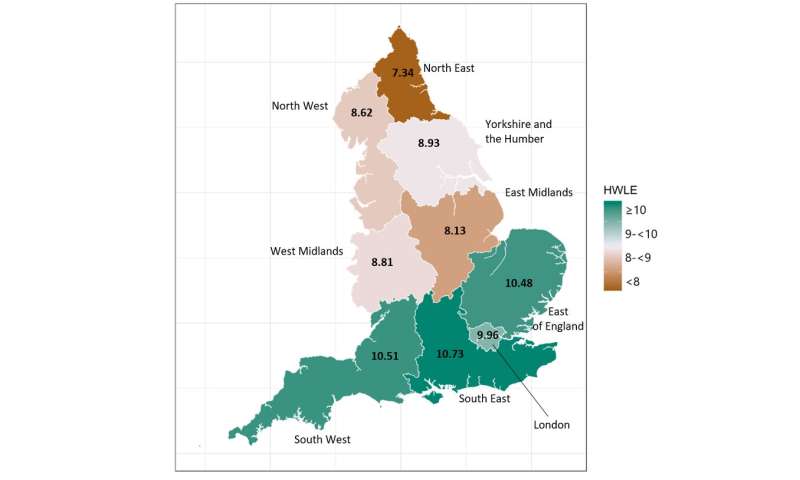

Regional map showing average number of healthy working years expected from age 50 in England. Credit: Parker et al, 2020, Author provided

Regional map showing average number of healthy working years expected from age 50 in England. Credit: Parker et al, 2020, Author provided