Wed, November 30, 2022

Amanda Slaunwhite, a senior scientist at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control and an assistant professor in the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, is one of the researchers involved in the study. (Cory Correia/CBC - image credit)

A new study has found the odds of a fatal drug overdose are about 30 per cent higher in rural areas of British Columbia than in urban centres and concludes a lack of access to harm reduction services may partly explain the elevated risk.

The study, conducted by researchers from the B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) and the University of British Columbia (UBC), was published in mid-November by the online journal BMC Public Health. The research team used overdose statistics from 2015 to 2018 to determine fatal overdose odds ratios.

One of the researchers is Amanda Slaunwhite, a senior scientist at the BCCDC and an assistant professor in the School of Population and Public Health at UBC.

"Peers have been telling us for quite some time that they're concerned about overdose in rural and remote places in B.C.," Slaunwhite told CBC.

"And we've also seen from the coroner monthly reports that northern and rural areas tend to have the highest rates of fatal overdose in B.C., and so we wanted to understand more about that — to really understand the geography of fatal overdose and if where you live has an impact on the likelihood of an overdose being fatal."

Toxic drug crisis serves as backdrop for study

The study looking into the odds of rural and urban fatal drug overdoses comes at a time when B.C. is in the midst of a toxic drug crisis. From April 2016, when the province declared a public health emergency, to June 2022, more than 10,000 people have died from toxic illicit drugs.

In October 2022 alone, the B.C. Coroners Service said at least 179 British Columbians died from toxic drugs. That number, released Wednesday, brings the total number of deaths to 1,827 between Jan. 1 and Oct. 31.

According to the study, illicit drug overdose is "the foremost cause of unnatural deaths in B.C., exceeding all other causes combined."

The study notes that the primary cause of the overdose crisis in B.C. has been the contamination of the illicit drug supply with fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid. Fentanyl, the report says, was detected in about 90 per cent of the 1,550 fatal overdose cases in B.C. in 2018.

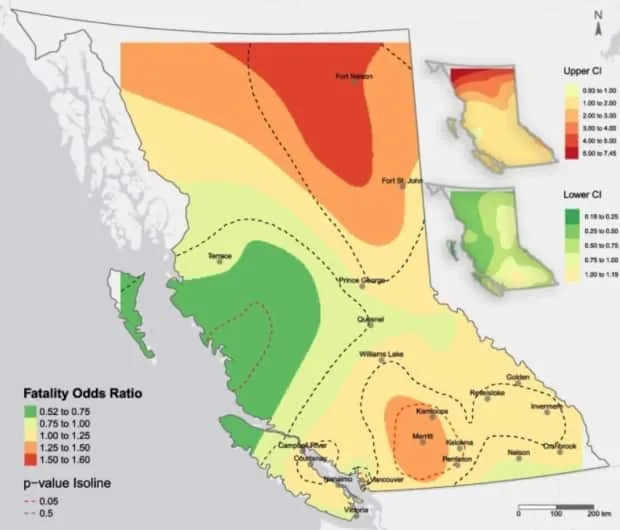

Provincial map shows hot spots and cold spots

Geographically, the most significant "hot spot" on the map for the odds of fatal overdose is an area in B.C.'s far north. That area includes the community of Fort Nelson, which has a population of about 3,400.

The biggest "cold spot" cover most of Haida Gwaii, the northern tip of Vancouver Island and a stretch along B.C.'s Central Coast, moving inland toward the west of Prince George and Quesnel. Population density in that area is low.

Submitted

Slaunwhite says hot spots and cold spots on the map are consistent with how much access people in those areas have to harm reduction services.

Bringing the picture down to a city level, she says the study found that people living in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver — a cold spot on the map — had lower odds of a fatal overdose because "there are lots of overdose prevention sites" in that area.

Advocate has on-the-ground perspective on services

Charlene Burmeister, the founder of the Coalition of Substance Users of the North, says the conclusion of the report — that lack of access to harm reduction services in rural locations may be a factor in the elevated risk of overdose deaths in these areas — is consistent with what she sees on the ground.

"Some rural locations in the north have … access to no harm reduction and people with lived and living experience have to navigate the best they can to get access to supplies," Burmeister said in an interview with CBC.

Burmeister lives in Quesnel, a city of about 10,000 people located in B.C.'s central Interior, 120 kilometres south of Prince George. She's also a stakeholder engagement lead with the BCCDC's harm reduction team.

In Quesnel, Burmeister says accessibility to harm reduction services is "much better" than in some northern B.C. rural communities. She says Quesnel residents can access services that run until 11 p.m. and receive assistance on the streets from a community outreach team. But even in Quesnel, she says more could be done.

"Quesnel certainly could use more programs and programs that kind of support people [with] more holistic and wraparound services," she said. "Definitely, we're lacking in that."