The Literary Note

Image by Cole Keister.

Steve Stern. A Fool’s Kabbalah: A Novel. Brooklyn: Melville House, 2025. 287pp, $19.99.

Omer Bartov, Israeli-born, renowned scholar of the Holocaust, has said lately that the genocide of Jews in the European 1940s is now fixed in history along with the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. The way we look at the 1940s, even within a splendid novel of Jewish history, is now different, can only be different.

At the end of A Fool’s Kabbalah, a very remarkable literary mixture of humor and horror, the beaten and hungry remnant of a Jewish shtetl in Eastern Europe is marched into a synagogue by the German invaders, the doors are locked and the building set afire. Horrible enough in itself, the deadly fire and the moral indifference of the Germans can only remind us today of bombs falling upon the trapped and hungry non-combatants in a zone now become historical for its vast use of prosthetics to replace the destroyed limbs of children. The historical narrative seems to have been turned upside down, and the world weeps.

Let us try to take a step back. The literature about Eastern Europe, including the Jews of Eastern Europe from the late nineteenth century to the end of the Second World War, has been growing by leaps and bounds in recent decades. Out of this swirling mass of fiction and mostly non-fiction comes a fine novel, not really “Marc Chagall on LSD” as a blurber suggests on the cover, but remarkable enough in itself.

One major theme of the emerging scholarship, perhaps one of the most surprising in several ways, is the deepening contextualization of the Jewish experience. In recent years, for instance, rich histories have been written about the (Jewish) Bund, with a following of tens or hundreds of thousands in the middle 1930s, at a time when Zionism remained marginal, attracting only modest interest. This is already far from the Hollywood, or for that matter the Israeli version of modern Jewish history. But there are larger themes as well.

The most important concerns the locus of the mass of pre-Holocaust Jews. Historians have explained that “Eastern Europe,” in the sense of the Russian-dominated East Bloc, did not exist because no one thought of the region in this compact and cohesive sense. The dense, vastly complicated but also very largely rural or semi-rural web of communities Jewish and Gentile had been divided and redivided by nationality, sometimes armored by the State or by religion, for centuries.

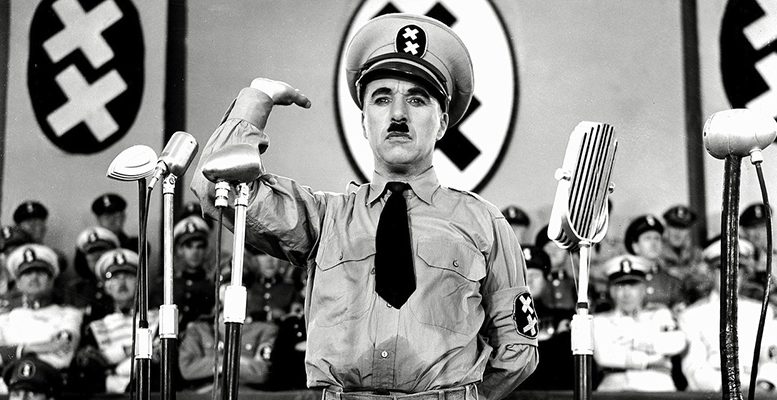

The First World War, in this light, might be called the beginning of something or equally, the end. Military hardware, newly organized and expanded armies exceeded in their destructive power all expectations. The Europe that emerged from the conflict tilted to the British-French side thanks only by the appearance of the Americans. Europe was widely viewed as exhausted, “an old bitch gone in teeth,” as Ezra Pound inelegantly put it.

Socialist redemption, the spreading of Revolution from East to West, might have changed world society. The US presence also guaranteed it would not be so.

But the human geography of Eastern Europe did not change to suit the redrawing of states. In considerable zones, the outside world of State authority remained or at least seemed distant, villagers and national leaders often with little in common. Folk customs, framed around very particular understandings of religion and culture, remained insular within local and regional and local languages or mini-languages. Almost as if the Turks or some other kingdom still ruled and demanded tax revenues but otherwise remained mostly at a distance.

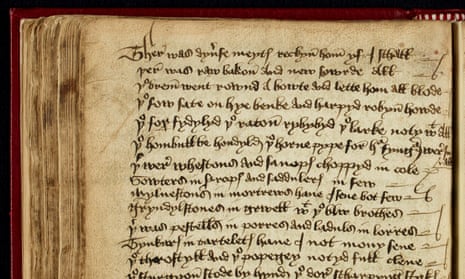

Thus the survival of quasi-nationalities. Among these, we can count the shtetl Jews, their lives varying from place to place but with the same anti-Semitic enemies on hand, whipped up from time to time by the authorities. In hundreds of these villages, a sensibility of Yiddishkayt or “Yiddishness” dominated, not exactly a Jewish nationalism and far from Zionism. The great anarchist scholar of Yiddish literature, B. Rivkin, insisted that on holidays, the insular shtetl was “outside of time,” much as Mikhail Bakhtin viewed the holidays of the European Gentiles in the Middle Ages.

In villages closer to cities or within the range of growing commerce, Yiddish could be seen already as the domestic workers’ language that even the matrons of the Jewish lower middle class regarded as quaint but useful to communicate, by way of a supposedly lesser tongue. That is to say, unlike the German, Russian or some other dominant language spoken by educated Jews.

Now imagine these Jews, middle and lower class, in villages ruled largely by the merchant class and the rabbis, as they increasingly interacted with the outside world. Socialists and later Communists learned from experience that they needed to speak and write in Yiddish to reach the less educated but poorer and often more revolutionary-minded Jews. That world outside had grown closer in the First World War, so much so (as an octogenarian lady told me in 1980) that the (first) German invasion could be remembered as mainly benevolent, bringing education and medicine, vastly better than actions of the local peasants.

Meanwhile, thanks to both the earlier surge of Jewish population (higher calorie counts increased birth rates exponentially over the course of the nineteenth century) and the departure of emigrants who could send back money to their families, the shtetls survived and by historic measure, at least, could be said to have flourished—even as the young and adventurous continue to escape, take up socialist ideas or both.

All this is the shtetl world of Steve Stern’s novel, thrown into crisis by the Second World War. Not that that action takes place entirely in the shtetl or in the 1940s. Gershom Scholem, the great scholar of Judaica but also the great friend of Frankfurt School theorist Walter Benjamin, is on hand to discuss matters of Jewish destiny and to reflect, mostly after the Holocaust, on the meaning of it all. In mystic terms. Understandably: rationality could hardly explain the Holocaust.

Walter Benjamin famously struggled, before his suicide in 1939 at the French border, to reconcile Marxism and Mysticism, with Sholem a modern master of Jewish mystical traditions. The two intellectual giants had plans or at least visions of what European Jewish life might become in decades again. Sholem worried that the still-unpopular Zionist project would betray and thus negate its spiritual roots. Benjamin sought some kind of redemption in the world of material objects and geographical places, a counterpart to Chagall and other Jewish artists surveying centuries-old Jewish temples and other buildings tucked away in Russia, sketching the nearly forgotten art and design in the years shortly after the Revolution.

When we leave these two, Benjamin forever and Sholem for some years, we find ourselves in the forgotten village of Zyldzce. Sometimes Poland, sometimes Byelorussia, sometimes Lithuania, the borders shifted and the rulers were never friendly to the Jews. Something terrible happens in 1940. The occupying Red Army had repressed the antisemitic peasants, and even greeted Jewish villagers with socialist sympathies. When the Russians withdrew, the Germans took over.

The dangers around the villagers understandably prompted a renewed interest in the traditions of mysticism. What Gershom Sholem would find as an empty wreck of a settlement, only a few years later, had been a hotbed of Talmudic discussion. It had also been a society of sharply divided classes, with traditional leaders become the collective mediators with the occupiers…..as they had in the earlier world war and in so many other past incidents, pogroms included. They, the (relatively) rich and powerful, had “handled things.” They would again, or so they were convinced.

The last several years of village life and culture dragged on, with the Germans now in charge, almost as if in a parody of the centuries-old practices. Religious ceremonies and food (when it could be obtained), weddings of fools with the accompaniment of the klezmorim, all as usual, even with the shadows growing more terrifying week by week. Thus the village fool, a famous figure in shtetl life and lore, entertains the German invaders so as not to be killed himself and perhaps to spare his fellow villagers who are abused and threatened more and more as the war continues.

Back and forth we go to Gershom Sholem, sometimes to his friend Hannah Arendt—herself only a few years from sharing the bed of the great antiSemitic philosopher Martin Heidigger—and the memories he carries, pursuing the vanished libraries that he hopes to find and save.

The end is surely coming, the villagers ever-closer to doom. One last Purim is staged among the ragged, hungry survivors, but not without, even at the last moment, the touch of Jewish humor. Famously, in the quarrel between Jewish pessimist and optimist, the first insists that things can’t get worse, while the second insists, of course they can. And he’s right.

We may need even at this point to be awakened to the other Jewish world unseen in these pages, Jewish life in the USA, where wartime prosperity soared beyond all previous expectation. The rising middle classes are ridden understandably by a sense of terror for distant relatives, even as they enjoy in their own lives unprecedented high living, better apartments, food and life, for themselves. In fact, although we do not see it in the novel, “Russian War Relief,” organized very much by the Left, is also raising millions of dollars and raising public attention to the quandary of Europe’s surviving Jews. If only the War can end, the remnant can be saved, and world peace can follow the expunging of fascism from the globe. No such luck.