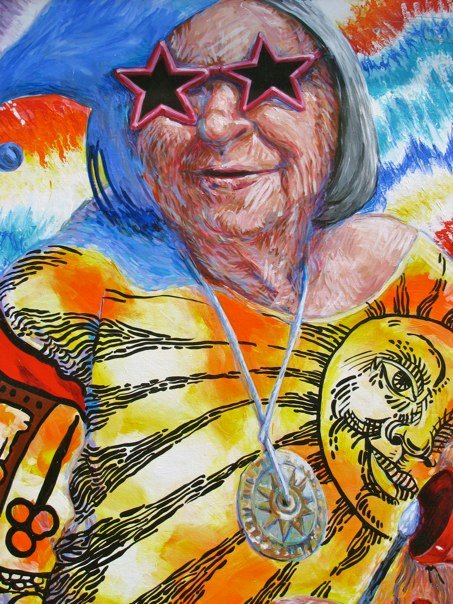

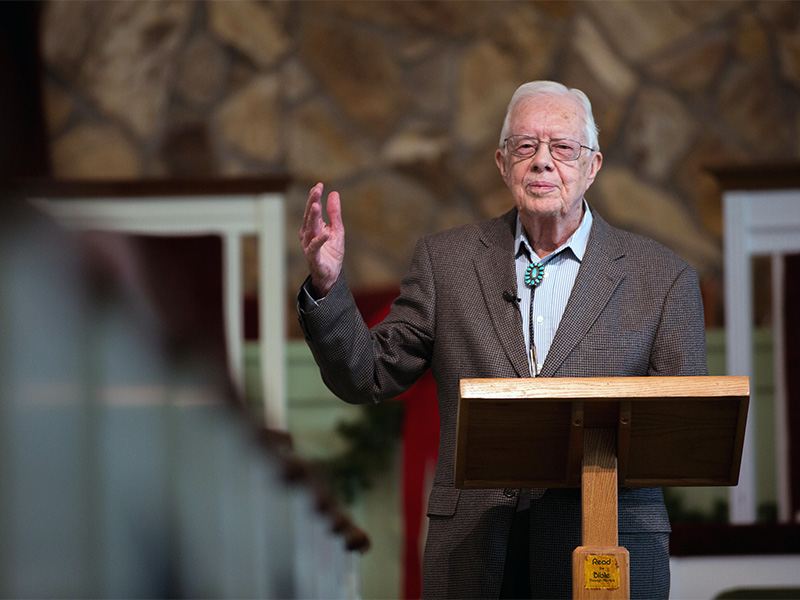

Photograph Source: Commonwealth Club – CC BY 2.0

After 100 years among us, Jimmy Carter is gone. Like a lot of people, I’m playing Ramblin’ Man in his memory tonight.

Saying good-bye to Jimmy Carter is complicated as Dickey Bett’s guitar. All complications considered, Jimmy was my favorite U.S. President during my lifetime. Nobody’s perfect, and a U.S. President’s imperfections are bound to cause immense death and destruction, as did Carter’s. Nevertheless, among modern American War Criminals-in-Chiefs, JC was relatively benign.

By the time Jimmy Carter took office, I’d spent a good portion of my youth protesting a crooked President (it’s all relative among Presidential criminals, but at the time, Dick Nixon was considered to be almost as ridiculous, nefarious and felonious as… Trump?), a horrific war (Vietnam) and the imperialist, capitalist system in general. I must confess I did this mainly because I longed to make out on a motorcycle with Che Guevara (or some facsimile, since he was dead), but also because I was vaguely aware the “system” sucked.

But in Jimmy Carter’s victory, I felt a surge of hope for America’s future, my future. I was just graduating from Yale, which had devolved from a progressive, antiwar academic haven personified by the Reverend William Sloane Coffininto a hotbed of Young Republicans creaming in their chinos over a cowboy California Governor whose gleaming Hollywood smile made me want to toss my scones all over my typewriter (yep, those were ancient times). So, I was grateful to see a Democrat in the White House who wasn’t LBJ. Would the future be bright with Jimmy?

With one foot still in the hippie “living-off-the-land” life (while the other was kicking through the big oak doors of the Ivy League), I liked that our new Prez was a peanut farmer. As I was dating an engineering student, I thought it was cool this farmer was also an engineer, albeit nuclear. Nuclear? Yikes! I was just starting to join the “No Nukes!” protests, and hoped (against hope) that his scientific expertise—not to mention his experience “saving” a Canadian nuclear reactor from a meltdown—would make him less pro-nuke than other politicians.

Nukes aside, I figured JC couldn’t be much worse than Tricky Dick or LBJ, and nothing was bringing back the glory of JFK, which really wasn’t all that glorious for Marilyn Monroe, among others. I saw Gerald Ford merely as a transitional figure, though I later learned he was actually one of our best Presidents, mainly because he didn’t do much besides fall down a few times and try to heal the nation from Tricky Dick’s violation. Oh, and then there was that semi-secret endorsement of Indonesia’s genocidal invasion of East Timor.

I thought it was a good sign when in 1977 on his first day in office, Jimmy Carter granted amnesty to any draft resister (or dodger).

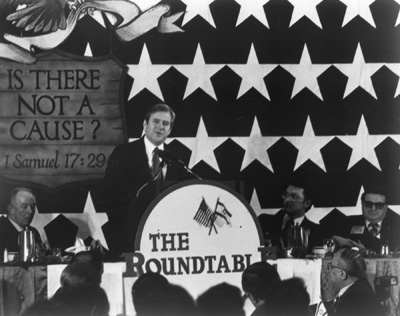

The fact that Carter was a devout “Christian” (JC loves JC) didn’t bother me because, at the time, I associated Christianity with the Reverend Coffin, the Berrigan Brothers and other antiwar Christians. Aside from a squawk or two from Anita Bryant and a young Jerry Falwell, Sr. (who was old even when he was young), the Church hadn’t quite turned hard Right… yet.

I appreciated this devout Christian President admitting in Playboy that he had committed “adultery in his heart.” Even before I studied sexology, I knew most people fantasized about all kinds of things, and I applauded a politician who was honest about it. That’s another thing: Jimmy didn’t seem like “a politician.” He certainly was one, but he had an aura of sincerity that is rare in politics, and it stayed with him until the end.

Being somewhat open about his sexual fantasies—even in Playboy magazine—must have been good for Jimmy’s sex life. Indeed, he was very happily married to Rosalyn Carter (1927-2023), his beloved Steel Magnolia, for 77 years, the longest marriage of any U.S. president.

When asked if winning a Nobel Peace Prize or becoming President was the most exciting thing that happened to him, Jimmy replied, “When Rosalynn said she’d marry me—I think that was the most exciting thing… Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything.” Gotta love a hubby like that.

Jimmy’s final farewell to his Rosalyn, read by their daughter Amy as Jimmy lay in a suit and tie on his hospital bed, had me—and countless other hopeful romantics sharing in this remarkable expression of intimacy from our devices—in tears. That scene, now a memory, moves me even more today, as I caretake my own beloved husband Max after his stroke.

However, I must admit, my affection for Jimmy Carter stems from the fact he gave me a job, and was a pretty good boss, as bosses go.

Getting a government job was never on my professional wish list. Actually, I wasn’t eager to go into any *profession,* partly because I was too lazy to get up and put on my jeans and tie-dyed T shirt for a 10am class, so how was I going to force myself into a power suit for a 7am power breakfast?

Nevertheless, there I was, six months into the Carter administration, graduating Yale with (almost worthless) honors, watching my classmates go off to Wall Street, law school, med school, other higher education or expensive parent-paid years abroad, and I just didn’t know what to do with myself (confession: I still don’t). I was pretty good at playing the game known as “school,” and I liked it well enough. However, I was starting to get (to use a much-maligned term) “woke” to the fact that I was not just learning, but also being subtly yet firmly indoctrinated into the same war-making system I was protesting. So, I decided to take a few years “off” before submitting (yes, higher education is like BDSM submission with all the restraints, punishments, protocols and pain) to more schooling.

Also, I was broke. And my voluminous student loans, on top of rent, on top of my fun-but-low-income lifestyle, was not putting money in my fledgling Bank of New Haven account.

So, I got a job working for Jimmy Carter, one of those government jobs I thought I’d despise, but it turned out to be one of my greatest jobs ever. Sometimes I even had to be at “work” by 7am(!), but never in a power suit. More likely tights, a leotard and maybe a mask. What kind of job did I have?

I was a New Haven City Mime.

Stop laughing! I’ve already heard all the stupid mime jokes you can muster, and I am the first to admit, mimes can range from mildly annoying to downright nauseating, even when they’re good, and I wasn’t that good. Let’s just say, I was no Marcel Marceau—who actually performed for a smiling Jimmy Carter and bemused Rosalyn and Amy—and Marcel was not as good as the master Jean-Louis Barrault (check out his moves in Children of Paradise). However, I was decent—I’d taken a few mime classes as a Theater major at Yale and mimed a bit in a Commedia Del’arte troupe of Yale grads and dropouts—or at least good enough to ace an audition for performing artists in the CETA(Comprehensive Employment & Training Act) program, which had been signed into law by Nixon (even the worst Presidents do some good), but ramped up to its highest levels under Carter. So, I was hired as a CETA City Mime.

Are you laughing even harder now? Many people (especially Reagan Republicans) found my job as a CETA City Mime to be the epitome of frivolous government, but not the sad citizens I made smile as they trudged across the New Haven Green, nor the tunnel-visioned commuters that broadened their perspectives through my silliness, nor the sick, the disabled and the seniors I distracted from their pain, nor the “inner city” students I taught to dramatize their feelings and ideas, some of whom went on to make movies, music and other forms of art, some of it great art.

I never met Jimmy, but I did a little goofy miming for his Veep’s wife, the Second Lady, Joan Mondale, at the Wisconsin Mime Festival, which she graciously tolerated as the cameras clicked away, splashing our cheer all over the papers.

Moreover, I was no longer broke.

So, Jimmy Carter gave me a job—a pretty damn wonderful, fun, sexy, creative, meaningful and (I think) helpful-to-the-community job… with health benefits! And I thank him for that. It was my first job as an artist, and I held onto it until Rhinestone Cowboy Reagan rode in and shot CETA dead as he shot dead or crippled many government programs, like Welfare, Social Security, Medicaid, Food Stamps, and federal education, while beefing up the U.S. military and cutting taxes for the rich.

Carter presided over an ostensibly peaceful time when Americans were in the grip of the “Vietnam Syndrome.” It was a good grip; at least, it felt pretty good to a peacenik like me (though it enraged the war profiteers), since this reluctance seemed to keep us out of war. I say “seemed” because, little did I know that, while I was pretending to climb through imaginary windows as a CETA City Mime on the New Haven Green, assuming my country was truly “at peace,” my boss President Jimmy Carter’s militantly anti-Communist National Security Advisor, Zbignew Brzezinski (“Morning Joe” Mika’s dad), was laying the military groundwork for 9/11.

9/11? If I’d known what was happening, it would have made my head spin (which would have been a neat mime trick). Quite honestly, it still does. In an effort to “undermine” the Soviet Union, President Carter, under Dr. Brzezinski’s earnest Trilateral guidance, armed and trained the ultra-religious Afghan Mujahideen against the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan and ultimately, Soviet occupation troops during the Soviet-Afghan war. One of the leaders of these Mujahideen, who later devolved into the religo-fascist Taliban, was a young Saudi millionaire named Osama bin Laden.

I observed the news with some interest, since I had just come back from a hippie trip through Afghanistan and fallen in love with the people and the roughly beautiful land. Years later, I was crushed to see the great Bamian Buddhasof Afghanistan—one of which I had climbed to the top—demolished by the Taliban. Then we got 9/11 and Bush’s War on Terrah… a Neocon nightmare, the seeds of which were planted by that seed-planting peanut farmer, my CETA GodFather, Jimmy Carter.

At least, he tried to make peace in the Middle East (sort of), bringing Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to Camp David for a handshake. I was never a Zionist; I’d even made out (on a motorcycle!) with a handsome Palestinian (who looked a little like Che Guevara) on my Jewish youth group’s trip to Israel, for which I got into big trouble. But I appreciated Carter’s efforts, which miraculously stood the test of time, though Israel’s current genocide is fraying them.

But this farewell is not an analysis or overview of Carter’s policies. I was too busy miming to pay serious attention to them.

I did notice that Jimmy had some intriguing relatives. Sometimes my mime job involved roller-skating, so I thought it was cool that his daughter Amy Carter essentially roller-skated through the White House, and then I thought she was super-cool when I learned she became an anti-apartheid, anti-imperialism activist with my Yippie hero, Abbie Hoffman, post-Presidency. Jimmy Carter’s brother, Billy, liked beer (some might say too much), but he actually handled his Billy Beer better than Washington’s current most prominent beer-lover Brett Kavanaugh. Jimmy’s sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton ministered to Larry Flynt when my old buddy Paul Krassner was editor of Hustler. Good times.

Though Nixon signed the Environmental Protection Act (score one more for Tricky Dick), Jimmy Carter established the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, tripling the size of the nation’s Wilderness Preservation System and doubling the size of the National Park System. He also had solar panels installed in the White House in 1979. Ronald Reagan removed them in 1986. Apparently, undermining Carter in both major and minor ways was a Reagan obsession.

The White House solar panels were essentially reinstalled in the early 2000s. What does that say about the two Presidents?

Unlike most high-level politicians of the 1970s, Jimmy seemed to genuinely enjoy the music of the times, and being a Georgian, he especially liked the Allman Brothers. In fact, he was friends with the band, and even said they “helped him win the White House,” because they played several concerts for him on the campaign trail.

Carter loved the blues, so of course, he’d have a little malaise. I remember his “Malaise” speech, how everybody—especially the Skull and Boners and other young Republicans that seemed to surround me—declared it just awful. I remember feeling a little self-conscious because I’d actually connected with that speech. I remember thinking that I understood the creeping “crisis of confidence in America,” because I was feeling it, and I was glad to have a President who dare to speak about it, even if he sounded like a depressed patient in one of those encounter group therapy sessions so popular back then.

Unsurprisingly, most Americans went along with my Young Republican colleagues, and declared the speech to be “politically tone-deaf,” sending Jimmy Carter into freefall. Then Iran fell to the Ayatollahs, Brzezinski’s preposterous hostage rescue attempt failed disastrously (for which Carter took responsibility), and Cowboy Reagan made a dirty deal on the down-low for the Iranians to hold onto the American hostages until he won the Presidency.

Then soon enough, both Jimmy Carter and I were out of our jobs.

What a stark contrast between Jimmy Carter, the relatively honest, slightly depressed, seemingly sincere Democrat who took responsibility for his mistakes and worked selflessly into his 90s, and Ronald Reagan, the fake sunshine cowboy Republican who spouted apple pie platitudes, never took responsibility for anything and slipped into senility before the end of his presidency.

Was Jimmy Carter a good president? It’s complicated. What’s certain is that he was a great former president.

He has gone on many post-presidential peace missions, supported Civil Rights and picked up a hammer to build homes for the poor through Habitat for Humanity in 1984, and kept doing it until he was 95. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002, but then so have many war criminals. Though Carter’s award “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development” somehow seems more sincere than most.

Over this past year and a half, I’ve often wondered what Jimmy Carter would have said about Israel’s current genocide. I can’t help but believe that he would have injected a dose of compassion for Palestine that we just don’t see these days from high-level American politicians, let alone Presidents, current or former.

So after a century of JC on Earth, like a lot of people, I’m listen to those Ramblin’ Man lyrics that so fit the occasion:

When it’s time for leavin’ I hope you understand that I was born a Ramblin’ Man

Whether he’s with Rosalyn, Jesus, or becoming one with that rich Georgia peanut-growing soil, farewell Jimmy Carter.