In the back country of Pakistan, you will find a unique ancient tribe of people who reside in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province. What makes them unique to most Pakistanis is the fact that many people in the tribe have blonde hair and blue eyes. Let me also add that they claim to descend from Greece in the time of Alexander the Great.

It is no secret that Alexander the Great had conquered these lands over 2,000 year ago and had occupied the mountains of northern Pakistan in which he would sow the seeds of a tribe that lives on to this very day. Many experts, scientists and authors agree that the Kalash Tribes shows all the signs, rites, history and possibly the DNA of the ancient Greeks.

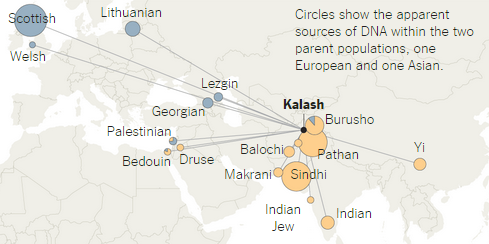

For example, in 2014, the New York Times reported that “The Kalash people of Pakistan were found to have chunks of DNA from an ancient European population. Statistical analysis suggests a mixing event before 210 B.C., possibly from the army of Alexander the Great.” Here is a DNA map from the NY Times article showing the possible influx of DNA into the Pakistani region.

A recent study prepared by Thessaloniki’s Aristotle University English Language Department assistant professor Elisavet Mela-Athanasopoulou shows the common elements shared by the language of the Kalash ethnic group in the Himalayas and Ancient Greek. The study proved common elements shared by Kalash language and Ancient Greek.

Who are the Kalash?

The Kalasha (Kalasha: Kaĺaśa, Nuristani: Kasivo) or Kalash, are a Dardic indigenous people residing in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. They speak the Kalasha language, from the Dardic family of the Indo-Iranian branch, and are considered a unique tribe among the Indo-Iranian peoples of Pakistan.

There are an estimated 3,000 Kalasha left in this beautiful tribe, and they have maintained their ancient culture and tribal rites for well over 2,000 years. Part of these rites include the making of distilled spirits and smoking marijuana. Rites that would be a death sentence in the religion of Islam. These rites are protected by a fierce tribal leader who enforces strict policies and keeps a watchful eye over his tribe. For example, a leader of the Kalash, Saifulla Jan, has recently stated, “If any Kalash converts to Islam, they cannot live among us anymore. We keep our identity strong.”

A Kalashi tribal man, Kazi Khushnawaz was recently quoted saying;

“Long, long ago, before the days of Islam, Sikander e Aazem came to India. The Two Horned one whom you British people call Alexander the Great. He conquered the world, and was a very great man, brave and dauntless and generous to his followers. When he left to go back to Greece, some of his men did not wish to go back with him but preferred to stay here. Their leader was a general called Shalakash (i.e.: Seleucus). With some of his officers and men, he came to these valleys and they settled here and took local women, and here they stayed.

We, the Kalash, the Black Kafir of the Hindu Kush, are the descendants of their children. Still some of our words are the same as theirs, our music and our dances, too; we worship the same gods. This is why we believe the Greeks are our first ancestors.”

The tribe dresses in what can be called traditional old orthodox Jewish-style. Kalasha women usually wear long black robes,

often embroidered with cowrie shells. The children wear their hair in orthodox Jewish-style ringlets and sport bright coloured topi hats. The women sometimes have tattooed faces, wear long black robes with colored embroidery.

The Kalash have no telephone, cars or modern amenities. They make their own bread, clothing, and live from agriculture. They celebrate a week-long Chamos festival with lots of singing, dancing, ritual, feasting and even the sacrifice of a goat.

During this time, the God Balomain (Baal) passes through the valley collecting prayers. Giant bonfire are lit on hills and torches carried by tribal members in honor of this God. They then dance in circles as they sing and chant around the fire just like can be found with the lost tribes of the American Phoenician Hebrew Indians and with the Irish Phoenician Hebrew in Ireland.

The Guardian reported in 2005 that they were a lost tribe who struggles for survival. Here is a quote from the article;

“Turquoise streams rush through leafy glades of giant walnut trees and swaying crops. Clusters of simple houses cling to steep forested slopes. Compared with many compatriots beyond their valleys, the Kalasha are charmingly liberal: drinking wine, holding dancing festivals and worshipping a variety of gods. Women wear intricately beaded headdresses, not burkas, and may choose their husband.”

“For me, the Kalasha are heroes, because they have reached the 21st century still living like their fathers,” said Athanasius Lerounis, a 50-year-old schoolteacher from Athens supervising construction of the centre, which is due to open next month. “We want to help them preserve that.”

In my many other articles on the Lost Tribes such as the Lost Tribe of Judah Found: The Scattered Children of Bab-El, Lost Tribe of Judah Found: The Bedas, and The American Indians and Phoenician Hebrews: 10 Commandments Found in Arizona I detail that many of these same traits such as the dress, food customs, religious rites and tattoos that is common in almost every single tribe that I have researched.

These tribes can be found all over the world from Egypt to India and all the way to Ireland and England in places such as Kent that was once known as the Old Kingdom of Jute which was originally Juteland or the land of the Jutes. Jutland, is regarded as Judah’s land. An adjective for Jute is “Jutish,” pronounced jootish. Kent is an early medieval kingdom said to be founded in the 5th century, in what is now South East England. Julius Caesar invaded the area in 55 and 54 BC, and he referred to the kings here as kings of Cantium.

How did the Kalash maintain their tribal rites and religious customs for over 2,000 years?

Even though the Kalash have kept their culture and maintained their tribal rites, many tribal members have been forcibly converted to Islam by the sword under penalty of death. The remaining tribal members are only the result of being isolated in the Pakistan mountains where they could escape and hide from Islamic crusaders. Professor of Islamic studies, U. Mass Dartmouth; and author, Brian Glyn Williams had recently written and article in the Huffington Post titled, The Lost Children of Alexander the Great: A Journey to the Pagan Kalash People of Pakistan. In it he writes;

“High in the snow-capped Hindu Kush on the Afghan-Pakistani border lived an ancient people who claimed to be the direct descendants of Alexander the Great’s troops. While the neighboring Pakistanis were dark-skinned Muslims, this isolated mountain people had light skin and blue eyes. Although the Pakistanis proper converted to Islam over the centuries, the Kalash people retained their pagan traditions and worshiped their ancient gods in outdoor temples. Most importantly, they produced wine much like the Greeks of antiquity did. This in a Muslim country that forbade alcohol.

Tragically, in the 19th century the Kalash were brutally conquered by the Muslim Afghans. Their ancient temples and wooden idols were destroyed, their women were forced to burn their beautiful folk costumes and wear the burqa or veil, and the entire people were converted at swordpoint to Islam. Only a small pocket of this vanishing pagan race survived in three isolated valleys in the mountains of what would later become Pakistan.”

A 2009 article in the Telegraph explains how this tribe was also recently the targets of the conservative Islamic militant group known as the Taliban. The Telegraph had written:

“The group, believed to be descendants of Alexander the Great’s invading army, were shielded from conservative Islam by the steep slopes of their remote valleys.

While Sikhs, Hindus, and Christians were slowly driven out of Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province by Muslim militants, the Kalash were free to drink their own distilled spirits and smoke cannabis.

But the militant maulanas of the Taliban have finally caught up with them and declared war on their culture and heritage by kidnapping their most devoted supporter.

Taliban commanders have taken Professor Athanasion Larounis, a Greek aid worker who has generated £2.5 million in donations to build schools, clinics, clean water projects and a museum.

They are now demanding £1.25 million and the release of three militant leaders in exchange for his safe return.

According to local police, it was Professor Larounis’s dedication to preserving Kalasha culture that Taliban commanders in Nuristan, on the Afghan side of the border that made him a target.

Confirmation of the Taliban’s role in his kidnapping came as their leader Mullah Omar urged American and Nato leaders to learn from the history of Alexander the Great’s invasion of Afghanistan and his defeat by Pushtun tribesmen in the 4BC.”

More research and videos of the Kalash

The Guardian

Feb 13, 2014 – Video released by Taliban calls on Sunnis to join fight against Kalashpeople and moderate Ismaili Muslims in Chitral valley.