27,000 man-made objects in Earth orbit, and counting: Space junk is here to stay

Space junk includes old satellites, rocket bodies, and fragments of exploded or decaying spacecraft

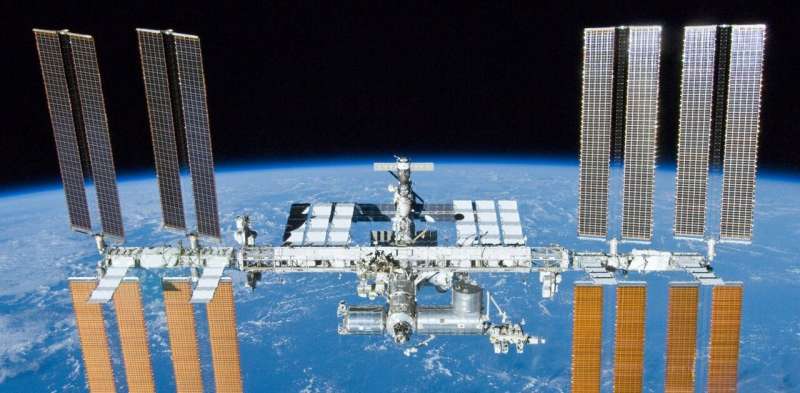

Representational image. News18

Adelaide: The US Vanguard 1 satellite and the rocket stage that delivered it to orbit in 1958 are pieces of cultural heritage. They date from a time when humans first attained the capability of reaching beyond our home planet to the stars. They also have the dubious honour of being the first space junk'.

NASA estimates there are around 27,000 human-made objects larger than 10 centimetres that can be classified as space junk that is, they do not have a useful purpose, either now or in the foreseeable future. These include old satellites, rocket bodies, and fragments of exploded or decaying spacecraft. The smaller bits, down to dust grain-size, number in the millions.

The problem is that collisions between this high-speed trash create more space junk. The worst-case scenario is known as Kessler Syndrome, an unstoppable cascade of collisions that could make parts of Earth orbit unusable.

It's an increasingly pressing situation as private corporations like SpaceX are slated to launch up to 100,000 new satellites by the end of the decade. Anti-satellite missiles, like the one tested by Russia in 2021, can add hundreds to thousands of new debris pieces in one event.

One of the big problems is we don't know enough about where what and how much space junk there is. This means we don't always know when a piece of space junk is about to collide with something, or how far we really are from Kessler Syndrome. This is a problem firstly, of observation and tracking, and secondly, of modelling and simulation of this highly complex data.

Lots of blind spots' are yet to be covered, like the tiny fragments and dust, and the higher orbits which are difficult to see from Earth's surface. Adding new instruments and techniques for observing space junk will address this.

For example, LeoLabs built a new space radar in New Zealand in 2019, picking up some of the blind spots in the Pacific region. HEO Robotics is developing observing capabilities in Earth orbit which can monitor the condition of spacecraft.

An increasingly popular approach is space traffic management. This aims to use space more efficiently and sustainably by coordinating and sharing information, such as that needed to avoid collisions, at the international and agency level.

International cooperation, of course, is an essential part of the solution. The Interagency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) facilitates cooperation in space debris research, and monitors the progress of ongoing cooperative activities. The IADC recommends each mission has a debris mitigation management plan.

The UN through the Office of Outer Space Affairs and the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space is also a key international organisation.

The UN released the Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities in 2018. Among other things, the guidelines emphasise the role of national governments in ensuring satellite operators under their jurisdiction don't contribute to the debris problem.

The UN, NASA and European Space Agency have had guidelines on design for minimising debris for nearly thirty years. The recommendations for end-of-life planning state that no spacecraft should remain in its mission orbit for longer than 25 years. Many think even this is too long.

Another end-of-life strategy is to passivate' a spacecraft. Here, all of the fuel, battery power, and high-pressure liquids are expended or exhausted, to reduce the risk of explosion.

But by some estimates, up to 60 percent of all new satellites launched don't comply with debris mitigation guidelines. It seems the incentives to preserve space for future generations aren't yet enough to sway commercial and government operators.

So what about cleaning up orbit? How can we remove the junk that is already up there?

Natural decay is the do-nothing strategy. Earth's atmosphere acts as a space junk waste management system by dragging objects into it, where friction and compression heat them to a burning point.

Eventually, everything below about 1,000 kilometres will get dragged back in.

The problem, of course, is that we keep adding new stuff, and it could be hundreds or even thousands of years before some junk re-enters.

Additionally, there's growing evidence that this is not the ideal solution it appears. The incineration creates alumina and soot particulates that cause the Earth's protective ozone layer to decay a problem we thought we'd already solved.

Options for active removal include nudging objects into the atmosphere, or pushing them to less congested orbits, also known as graveyard orbits, where they aren't such a collision risk a choice of down or up.

Methods which have been proposed or are under development include nets, harpoons, lasers, tethers, sails and specialised vehicles. In 2019, Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTL) successfully tested a harpoon for space junk capture in orbit.

The leaders in this field are Singapore-based Astroscale. In collaboration with SSTL, they launched the Elsa-d system in March 2021. Elsa-d is testing rendezvous manoeuvres needed to dock with space junk and then remove it.

Another project is the Swiss ClearSpace1. Under contract to the European Space Agency, they are developing a spider-clawed spacecraft to grab and de-orbit old satellites. It's planned for launch in 2025.

Getting rid of old space junk doesn't have to mean destruction. Recycling could give space junk a purpose making it a resource rather than rubbish. For example, old satellites aren't always dead'. They may have power and communications and could be repurposed to do new science.

The materials could be recycled into rocket fuel, technology which Neumann Space is developing in Australia, or scavenged for building materials. Old rocket bodies, one of the most dangerous classes of junk, could be turned into space habitats or laboratories.

However, passivation reduces the potential for repurposing a satellite or rocket body. Refuelling on-orbit is a way to extend the usable life of a spacecraft, and a number of companies are working on this technology.

Another promising direction is thinking creatively about new materials. A Japanese project has been looking at wood as housing for small, short-lived low Earth orbit satellites. Wood won't last as long in orbit as the usual spacecraft materials and does not create alumina or soot when it burns in the upper atmosphere.

The problem with any successful technology for removing an old spacecraft from orbit is that it's also effectively an anti-satellite weapon. This means treading very carefully indeed to avoid the situation that no-one wants war in space.

Earth orbit is a classic example of the tragedy of the commons', where maximising national, or commercial, gain ruins the resource for all users. It's important to remember that not everyone is equally responsible for creating space junk. Most of it belongs to the US, Russia and China. But the advent of the private mega constellations is likely to change that.

One thing is clear: orbital space is never going to return to its pre-1957 pristine state. Space junk is here to stay.