BAN PALM OIL

Migrant orangutans learn which foods are good to eat by watching the locals

Migrants male orangutans ‘peer’ at role models to learn about new foods, especially those hard to process or rarely eaten

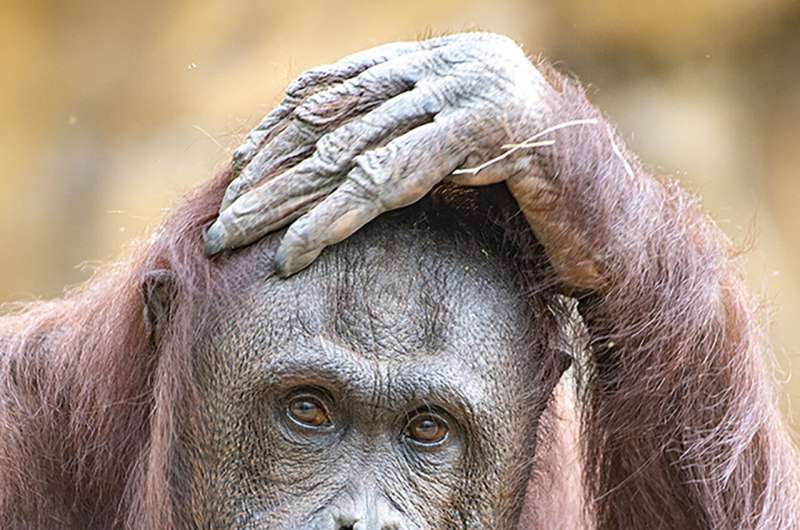

IMAGE: AN UNFLANGED MIGRANT ORANGUTAN MALE (ON THE LEFT SIDE) AND AN ADOLESCENT LOCAL ORANGUTAN FEMALE (ON THE RIGHT SIDE) ARE PEERING AT EACH OTHER. ORANGUTAN SPECIES: PONGO ABELII view more

CREDIT: CAROLINE SCHUPPLI, SUAQ PROJECT, WWW.SUAQ.ORG

Orangutans are dependent on their mothers longer than any other non-human animal, nursing until they are at least six years old and living with her for up to three years more, learning how to find, choose, and process the exceedingly varied range of foods they eat. But how do orangutans that have left their mothers and now live far from their natal ranges, where the available foods may be very different, decide what to eat and figure out how to eat it? Now, an international team of authors has shown that in such cases, migrants follow the rule ‘observe, and do as the locals do’. The results are published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

“Here we show evidence that migrant orangutan males use observational social learning to learn new ecological knowledge from local individuals after dispersing to a new area,” said Julia Mörchen, a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Leipzig, in Germany, and the study’s lead author. “Our results suggest that migrant males not only learn where to find food and what to feed on from locals, but also continue to learn how to process these new foods.”

Mörchen and colleagues showed that migrant males learn this information through a behavior called ‘peering’: intensely observing for at least five seconds and from within two meters at a role model. Typically, peering orangutans faced the role model and showed signs of following his or her actions with head movements, indicating attentive interest.

Male orangutans migrate to another area after becoming independent, while females tend to settle close to their natal home range.

“What we don’t yet know is how far orangutan males disperse, or where they disperse to. But it’s possible to make informed guesses: genetic data and observations of orangutans crossing physical barriers such as rivers and mountains suggest long-distance dispersal, likely over tens of kilometers,” said Mörchen.

“This implies that during migration, males likely come across several habitat types and thus experience a variety of faunistic compositions, especially when crossing through habitats of different altitudes. Over evolutionary time, being able to quickly adapt to novel environments by attending to crucial information from locals, likely provided individuals with a survival advantage. As a result, this ability is likely ancestral in our hominin lineage, reaching back at least between 12 and 14 million years to the last common ancestor we share with orangutans.”

The authors analyzed 30 years of observations, collected by 157 trained observers, on 77 migrant adult males of the highly sociable Sumatran orangutan Pongo abelii at the Suaq Balimbing research station in Southwest Aceh, and 75 adult migrant males of the less sociable Bornean orangutan Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii at the Tuanan station in Central Kalimantan. They focused on every observation of peering behavior during 4,009 occasionswhen these males were within 50 meters of one or more neighbors, who could be adult females, juveniles, or adult males.

Peering by males was observed 534 times, occurring in 207 (5.2%) of these associations. In Suaq Balimbing, males most frequently peered at local females followed by at local juveniles, and least at adult males. In the less sociable population of Tuanan, the opposite held: males most frequently peered at adult males followed by immature orangutans, and least at adult females. Migrant males at Tuanan may lack opportunities to peer at local females, as females are known to avoid long associations with them in this population.

Migrant males then interacted more frequently with the peered-at food afterwards, putting into practice what they learned through peering.

“Our detailed analyses further showed that the migrant orangutan males in our study peered most frequently at food items that are difficult to process, or which are only rarely eaten by the locals: including foods that were only ever recorded to be eaten for a couple of minutes, throughout the whole study time,” said Dr Anja Widdig, a professor at the University of Leipzig and co-senior author of the study.

“Interestingly, the peering rates of migrant males decreased after a couple of months in the new area, which implies that this is how long it takes them to learn about new foods,” added Dr Caroline Schuppli, a group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Konstanz, and co-senior author.

The authors cautioned that it’s still unknown how many times adult orangutans need to peer at a particular behavior to learn to master it. Observations suggest that depending on the complexity or novelty of the learned skill, adults may still use explorative behaviors on certain food items they first learned about through peering – possibly to figure out more details, strengthen and memorize the new information, or to compare the latter with previous knowledge.

An unflanged migrant orangutan male feeding on leaves from a tree fern, Akar Pakis Sarang Burung (Drynaria sparsisora). Orangutan species: Pongo abelii

CREDIT

Julia Mörchen, SUAQ Project, www.suaq.org

A flanged migrant orangutan male feeding on Rotan Tikus leaves (Flagellaria indica), Orangutan species: Pongo abelii

CREDIT

Guilhem Duvot, SUAQ Project, www.suaq.org

An unflanged migrant orangutan male feeding on Rotan Tikus leaves (Flagellaria indica) Orangutan species: Pongo abelii

CREDIT

Natascha Bartolotta, SUAQ Project, www.suaq.orgJOURNAL

Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Observational study

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Animals

ARTICLE TITLE

Migrant orangutan males use social learning to adapt to new habitat after dispersal

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

5-Jul-2023