Hugh Secord| June 1, 2023

Change is a good thing. Change, however, is not an easy thing

Machines replacing humans in the workplace has been a perpetual concern since the Industrial Revolution. In the early 1800s, the Luddites, a “radical” organization of textile workers protested the use of machinery in the industry as it effectively eliminated many of the craft jobs and replaced them with machines and unskilled factory labour. Moreover, the machinery advanced productivity and resulted in the factories needing fewer workers than the craftspeople that were displaced. The Luddites sabotaged the machinery to try to impede progress. In the end, they failed, but history will remember them. Today, anyone who seemingly resists the adoption of technology is often referred to as a Luddite.

Robotics and automation in general will continue to displace workers and result in some groups finding themselves unemployed. This is an unfortunate but inevitable consequence of finding better ways to produce more with less. However, before passing judgment as to whether this is a good thing or bad thing, we need to look at both the positive and the negative impact new technology will have on the workforce.

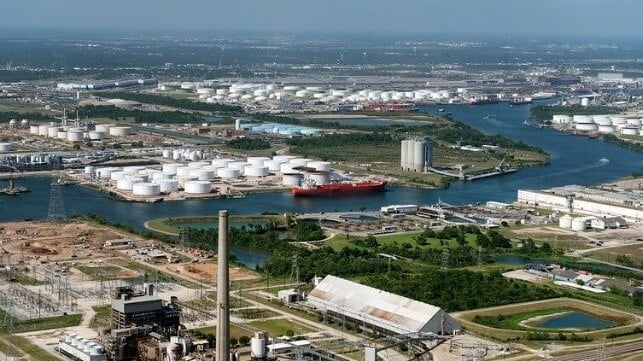

In mining, one of the immediate advantages to advanced technology whether in the form of autonomous haul vehicles or remote-controlled mining machines is that it removes workers from the dangers they could be exposed to at the workface. This could include exposure to hazardous substances (e.g., radiation in a uranium mine); noise; dust; loose falling material; moving heavy equipment; poor air quality; or any number of other hazards specific to what is being mined. Removing humans from the workface is the ultimate mitigating step to protect workers from the inherent dangers often associated with mining.

Safety is the key rationale for deploying new technology that eliminates the human operator. Notwithstanding, one should expect a dispute with organized labour no matter how compelling the safety argument is. Several years ago, I spoke to members of the Longshoremen’s Union on the west coast about the then relatively new technology [Hands Free Mooring (HFM)] that allowed a port operator to land a ship and secure it to a wharf completely by remote control and with no human intervention using giant suction cups. HFM units reach out to secure a ship during dockage, utilizing vacuum pads instead of traditional wire or rope lines. Ships are held by the mooring units which move up or down on rails recessed within the dock wall as the ship moves up and down with tides and waves. Once the ship is finished being loaded or unloaded as the case may be, the mooring units gently push the ship off the dock and release their grip, allowing the ship to proceed on its journey.

The Longshoremen Union objected to the use of this technology at the time because it represented a clear threat to jobs. However, the jobs that would be eliminated were amongst the most dangerous in the world. Many people are seriously injured or killed in the process of mooring ships with heavy lines or cables. The counter argument is not always rational when we are talking about something that radically changes how work is performed. More than just threatening jobs, technology challenges a way of life and a work culture for those dock workers.

This cultural disruption has the knock-on effect of changing how people in certain walks of life see themselves. The Longshoremen members see themselves as hard-working tough individuals who face danger in the performance of their duties. When a gang of these rugged individuals can be replaced by a single operator sitting in a control room which could be several hundred kilometers away, the impact can hardly be anything less than emotional. It takes away not just employment but eradicates identity.

Similarly, continuous mining methods using remote controlled boring machines and automated conveyor systems not only dramatically improves safety and productivity, but it also changes the very nature of mining. These methods replace face drill operators, explosive technicians, scalers roof bolters, and more. These workers are replaced by control room operators who are shielded from the noise, dust, and other inherent hazards. It is dramatically different work and will completely change the culture of mining.

The degree of technological advancement that is available in the mining sector will have a profound effect on how the industry is perceived. Mining is often seen as a rough profession suitable to certain hearty souls who relish the inherent danger that one implicitly associates with going underground and digging out valuable minerals. The new face (pun intended) of mining is much different.

The modern miner is a technician operating sophisticated equipment in the safety and comfort of a control room far removed from danger. The work environment is conducive to attracting and retaining a different kind of workforce that is more diverse. This is a key point. The transformation in the nature and makeup of the workforce is an important challenge for human resource practitioners. It is not as simple as retraining people in new technologies. It is truly embracing a complete revamping of the workforce mix and therefore operating culture.

This cannot reasonably be accomplished incrementally. It is about revolution not evolution. In the initial example above, the sabotage associated with the Luddite upheaval was an inevitable and arguably necessary reaction to dramatic changes caused by the introduction of revolutionary new technology. It is nice to sit in the comfort of our offices and imagine the front-line workers accepting just how wonderful their lives are going to be once they realize the positive impact the technology is going to have. Alternatively, one might think that the offer of a comfortable retirement package will ease some displaced workers into a new sedentary lifestyle. However, that is not the reality we live in. The introduction of technology disrupts lives and challenges how people identify with the work they currently perform.

With new technology, there will be new and interesting jobs. The front-line worker becomes a technical operator and is freed from manual labour, and other jobs emerge at the front line that require master crafts people of the highest order. Robots, electrical vehicles, autonomous haul trucks, and all matter of new equipment will require maintainers with extraordinary skills that largely do not exist today.

Certainly, given today’s digitization, many pieces of equipment are designed with modules that allow for quick maintenance and repair, and the work can be performed by semi-skilled technicians (think of an F1 pitstop). But at the other end of the scale, we will need problem solvers who have programming skills on top of deep mechanical knowledge on top of a sophisticated understanding of systems. These “masters” likely will have two or more trade tickets and a variety of experiences and will command a fortune in wages because of their superior skill set.

So, while many front-line jobs in mining will be replaced by machines and systems, we will see the emergence of a new class of workers who will be highly trained and qualified. The emergence of these technical roles will change the nature of this kind of work and disrupt the way these jobs are viewed by the public.

If we collectively manage the future transformation correctly, we will have to face the reality that a large group of people will be displaced and will be very unhappy. They will not only be displaced by machines, but they will also make way for a new class of worker who will command respect because of the significant investment they have made in learning a trade that not long ago did not exist. We will find these technical roles in mining, in the oil and gas sector, in the broader power sector (including renewables), manufacturing, supply chain, and anywhere that technology can be used to reduce exposure to danger and increase productivity by replacing people at the workface.

Hugh Secord is chief strategist at Oakbridges.