A dish so ubiquitous on menus people mistake it for a Western invention, butter chicken is as authentically Indian as Indian food gets, inventor’s grandson says

It was created by chance at a restaurant in Delhi owned by three Punjabi Hindu refugees, when a big group arrived late for a meal and the chefs had to improvise

Alkira Reinfrank Published 26 May, 2020

The story of butter chicken – like this one held by Hong Kong chef Palash Mitra – is one of three hard-working refugees, a hugely popular Delhi restaurant and an accidental flavour combination born out of necessity and leftover tandoori chicken. Photo: K.Y. Cheng

Few people, when tucking into a serving of butter chicken, would think about the history of the Indian dish. For Raghav Jaggi, however, this aromatic staple is more than a taste of home – it’s his family’s legacy.

His grandfather, Kundan Lal Jaggi, dedicated his life to tandoori cuisine and is one of three Punjabi Hindu refugees celebrated for inventing butter chicken.

Few other dishes can evoke such a passionate and varied response from diners but, whether it’s religiously ordered or desperately avoided, there’s no denying the dish has helped popularise Indian cuisine globally.

“Butter chicken is a lifestyle,” Jaggi, 39, says with a chuckle, from his home in New York.

The significance of his grandfather’s endeavours aren’t lost on Jaggi, who warmly remembers Friday afternoons as a boy in Delhi,

India, that were spent eating creamy butter chicken – called murgh makhani in Hindi.

“Butter chicken is a very critical and important part of the Indian culinary journey,” Jaggi says. “If you really look at Indian food and how popular it is in the world, some of the creations that my grandfather made in his kitchen are the reason Indian food is so popular.”

The dish is so ubiquitous on menus outside the South Asian country today that people often mistake it as a Western invention, like chicken tikka masala. But butter chicken, traditionally made with marinated chicken cooked in a tandoor oven and served in a creamy tomato gravy, “is as authentically Indian as Indian food gets”, Jaggi says.

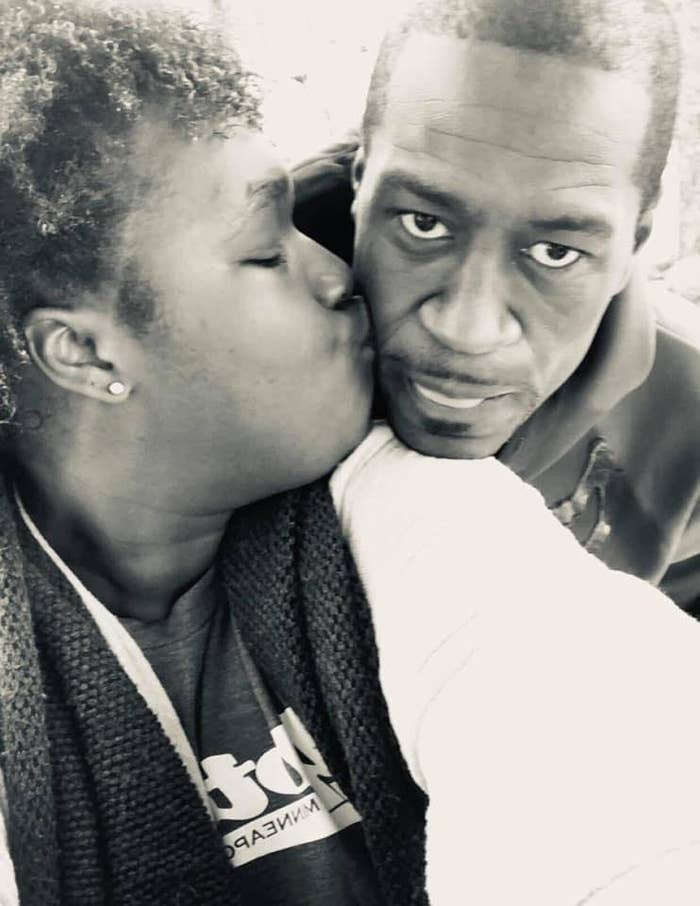

Kundan Lal Jaggi is one of three Punjabi Hindu refugees celebrated for creating butter chicken. Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

The story of butter chicken – which dates back to the late 1940s – is one of three hard-working refugees, a star-studded Delhi restaurant and an accidental flavour combination born out of necessity.

Partition of India in 1947, Kundan Lal Jaggi, Kundan Lal Gujral and Thakur Dass fled Peshawar – in northwest Pakistan today – for Delhi.

The division of British India into two independent states – Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan – displaced about 15 million people along religious lines. The death toll from that time of upheaval is still disputed, with figures ranging from 200,000 to 2 million.

In the pre-Partition days, Kundan Lal Jaggi and Kundan Lal Gujral had worked in a famed tandoori restaurant in Peshawar called Moti Mahal, while Thakur Dass worked across the road.

Mokha Singh Lamba (in the middle row, centre) and Kundan Lal Jaggi (far left, standing) in Peshawar. Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

“My grandad, like many other Hindu Punjabis, left everything that he had in what is now

Pakistan and moved to India. Delhi, particularly the area known as Daryaganj, became the hub for a number of these refugees,” says Jaggi, who describes his grandfather as an extremely resilient and humble man.

Working in kitchens is all Kundan Lal Jaggi knew. He left school at the age of 15 to make money, and began by cleaning tandoors, before moving up through the ranks to become a master of the clay oven, roasting meats and naans at extremely high temperatures.

Palash Mitra making butter chicken in a tandoor oven at Rajasthan Rifles restaurant in Hong Kong. Photo: K.Y. Cheng

Arriving in Delhi with few possessions, he decided to open a tandoori restaurant in the Daryaganj area with Kundan Lal Gujral and Thakur Dass. The trio named it Moti Mahal, after the closed restaurant from their hometown, with the blessing of its former owner, Mokha Singh Lamba.

One night, a few months after opening, a busload of refugees came late to the restaurant in search of a meal, but there were only a few dry tandoori chickens left.

“There were truckloads of refugees coming into the area, and at that time you never refused food to anyone,” Jaggi says.

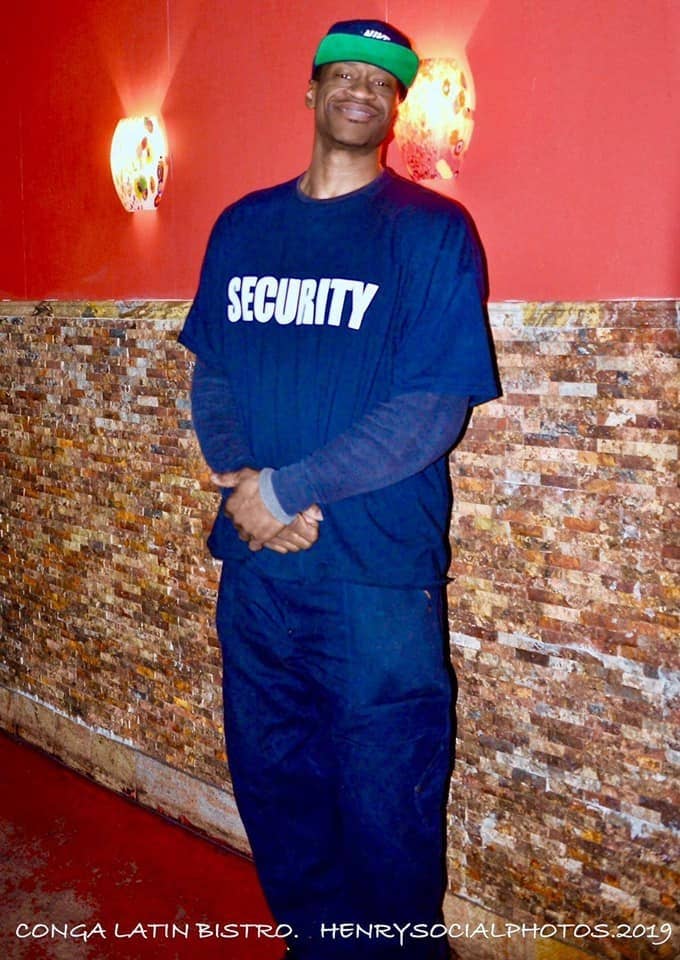

Moti Mahal’s original team in 1947 outside the restaurant.

Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

Kundan Lal Jaggi decided to create a simple sauce of cream, tomatoes and a few spices infused with the smoky tandoori chicken, “so that people could use the naan and dip it into the gravy if they were not able to get a bite of chicken”.

“It was rich enough to give them enough [sustenance] to survive another day, and it was totally by chance. Everyone loved the dish so much they asked for it again the next day. And the day after, the same thing happened,” Jaggi says. It was so popular, it was made a permanent fixture on the menu and became one of the dishes that defined the restaurant.

Moti Mahal was one of the most iconic restaurants in the Indian capital for the next 45 years, says Jaggi, and popularised tandoori cuisine.

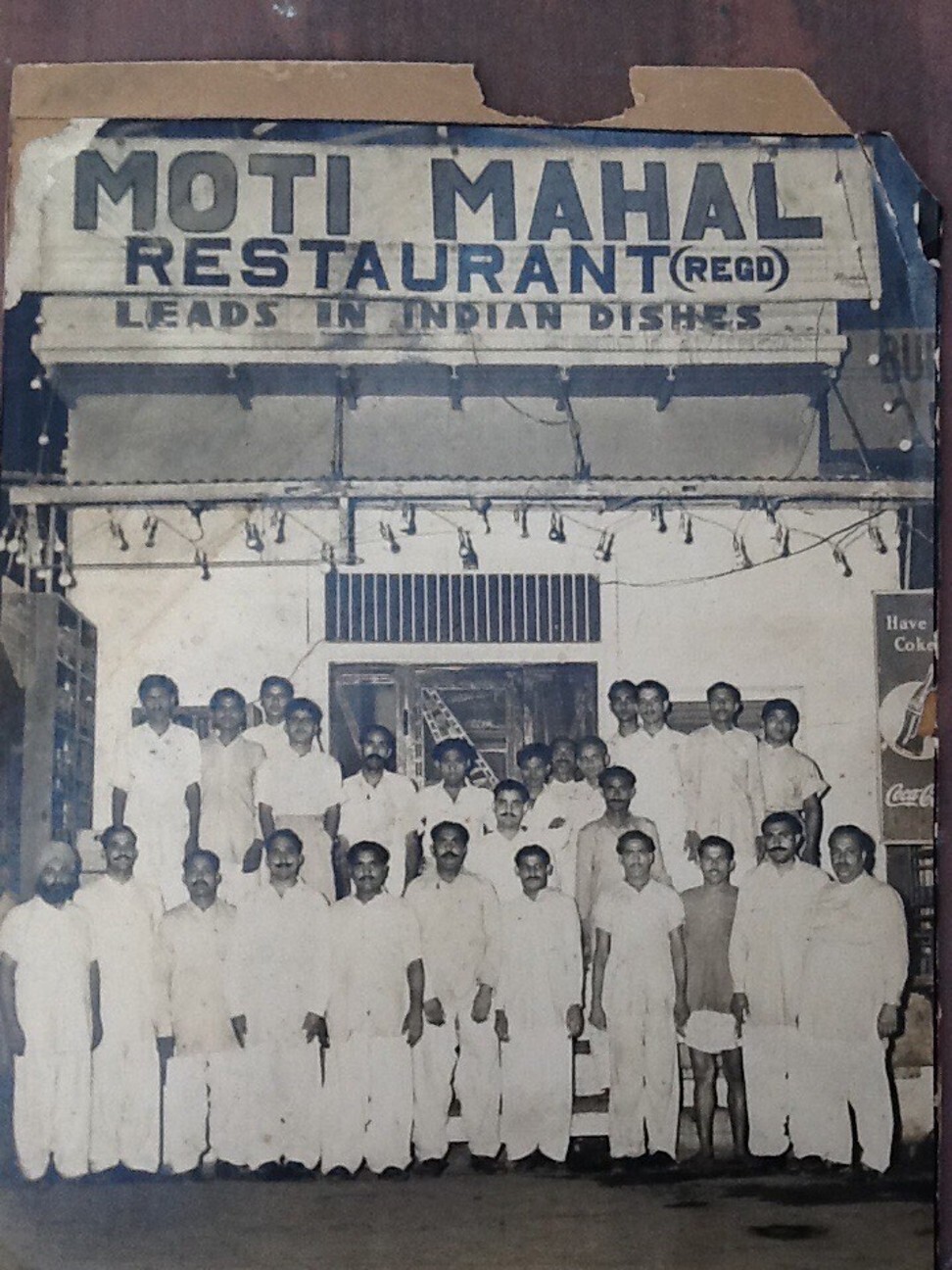

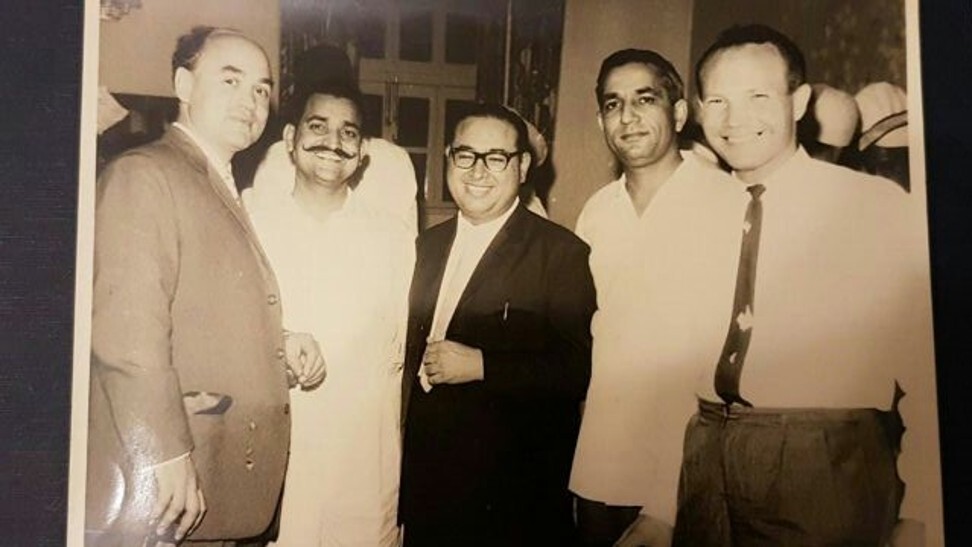

Kundan Lal Jaggi (second from left) with celebrity guests.

Kundan Lal Jaggi decided to create a simple sauce of cream, tomatoes and a few spices infused with the smoky tandoori chicken, “so that people could use the naan and dip it into the gravy if they were not able to get a bite of chicken”.

“It was rich enough to give them enough [sustenance] to survive another day, and it was totally by chance. Everyone loved the dish so much they asked for it again the next day. And the day after, the same thing happened,” Jaggi says. It was so popular, it was made a permanent fixture on the menu and became one of the dishes that defined the restaurant.

Moti Mahal was one of the most iconic restaurants in the Indian capital for the next 45 years, says Jaggi, and popularised tandoori cuisine.

Kundan Lal Jaggi (second from left) with celebrity guests.

Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

In the late 1940s in Delhi, most of the population was vegetarian, while the newly arrived migrants were meat eaters. To ensure vegetarians could enjoy a meat-free version of the dish, Jaggi says, his grandfather invented dal makhani, which has also found global fame.

“Moti Mahal was a turning point for India. People used to travel from abroad to eat there. It was a landmark,” says Palash Mitra, 39, head chef of the world’s first Michelin-starred Pakistani restaurant, New Punjab Club, in Hong Kong.

In the late 1940s in Delhi, most of the population was vegetarian, while the newly arrived migrants were meat eaters. To ensure vegetarians could enjoy a meat-free version of the dish, Jaggi says, his grandfather invented dal makhani, which has also found global fame.

“Moti Mahal was a turning point for India. People used to travel from abroad to eat there. It was a landmark,” says Palash Mitra, 39, head chef of the world’s first Michelin-starred Pakistani restaurant, New Punjab Club, in Hong Kong.

It attracted the likes of India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, former US President Richard Nixon, former US first lady Jackie Kennedy and countless Bollywood stars, Jaggi says.

Able to seat up to 350 people, Moti Mahal also helped introduce a dining-out culture to India. “Kundan Lal Jaggi represented his north Indian heritage really well and took Indian food out onto the world’s stage,” says Mitra, who is also the culinary director of Southeast Asian cuisine at the Black Sheep Restaurants group in Hong Kong.

“Kundan Lal [Jaggi] is probably one of the first Indian chefs-cum-restaurant owners in the true sense, like a French chef. He was the chef of his own restaurant, he was selling food commercially, he made a big business out of it.”

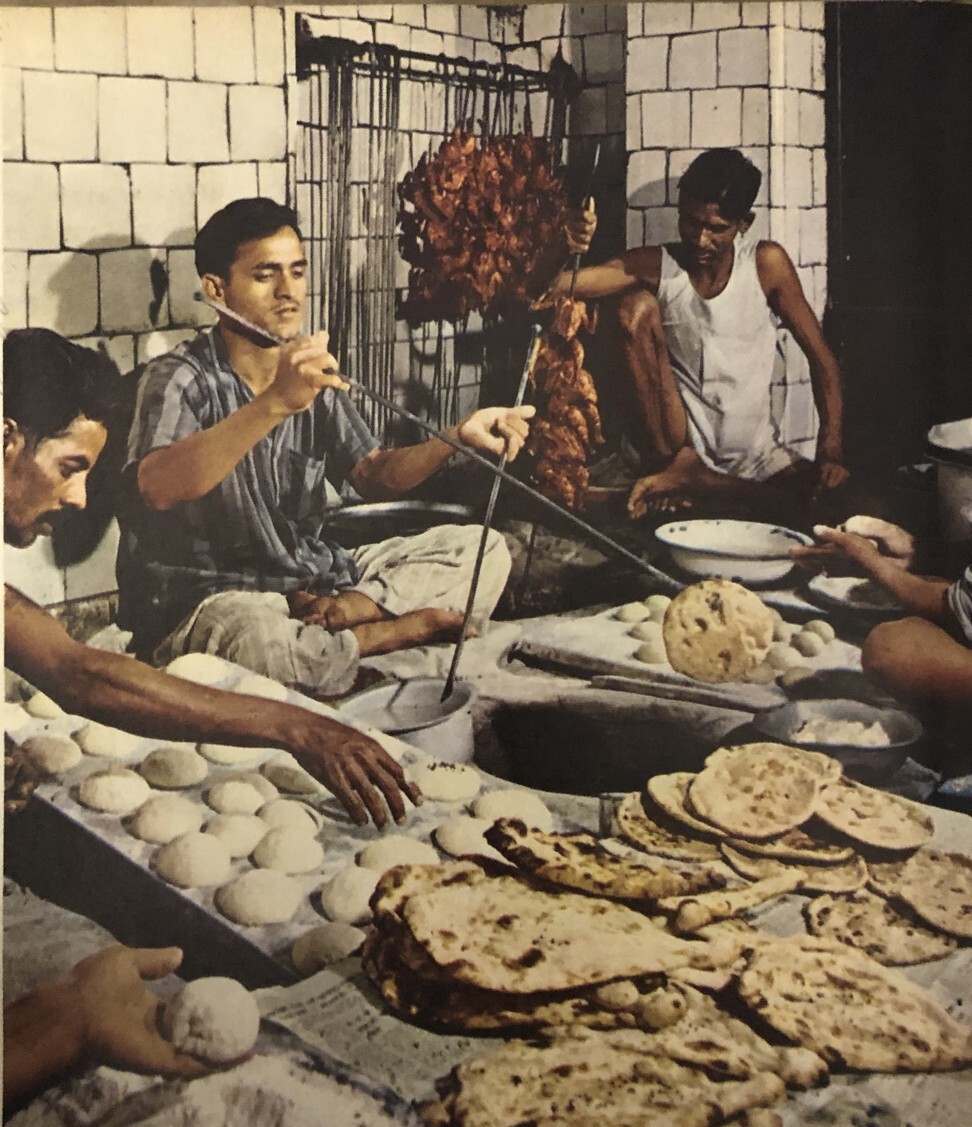

A picture of the Moti Mahal kitchen from the 1970s.

Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

To keep up with demand, the trio opened four venues across Delhi and even ran their own poultry farm, enabling them to acquire up to 600 chickens a day for their restaurants. In the 1950s, then-Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru appointed Moti Mahal as the official caterer of India’s Republic Day, meaning they needed to feed “a few thousand people in a single day”.

Mitra believes the invention of butter chicken was no accident. “He did a massive service to Indian cuisine and he should be celebrated more,” he says.

Mitra still remembers the first time he tried butter chicken as a 12-year-old. It was the first time he had eaten meat, and “the smokiness, the texture and flavour was something totally unique”.

“It was a turning point in my life. I said, ‘I am not going to eat vegetables any more,’” says Mitra, whose restaurants are known for their succulent meat offerings cooked in a tandoor oven.

Palash Mitra cutting up meat for butter chicken at Rajasthan Rifles. Photo: K.Y. Cheng

As chefs from Moti Mahal moved on to work at new restaurants or to open their own, they took the butter chicken recipe with them, says Jaggi – and the dish swept across India.

Mitra says the dish’s global spread coincided with migration of Indian labourers – specifically Punjabis – to the West.

“When they travelled, they took their food with them. You can take the Punjabi away from Punjab, but you can’t take the Punjab out of the Punjabi. So they will create butter chicken anywhere they go,” he says.

“Butter chicken is not the only dish that represents India or Punjabi food, but it significantly demonstrates the culinary history and landscape of the country.”

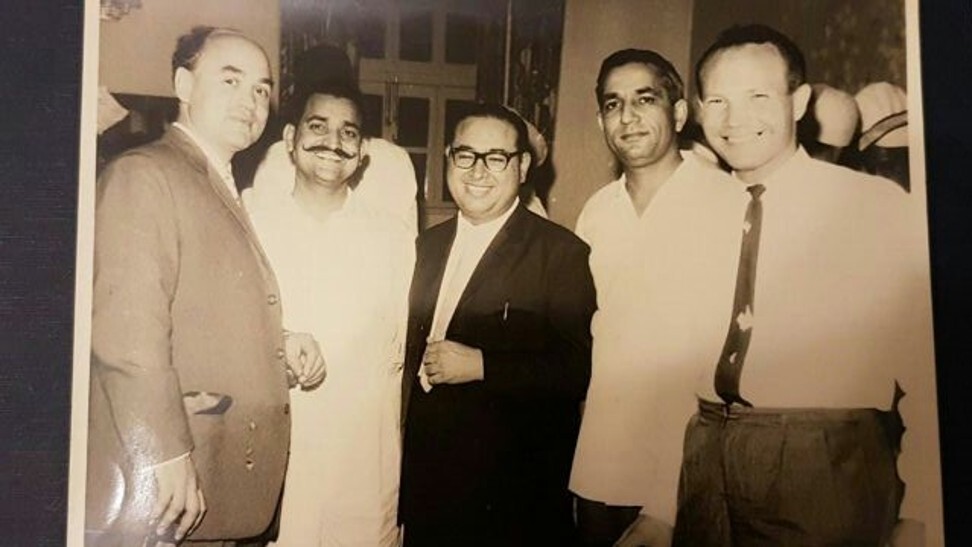

Last year, Raghav Jaggi (left) and Amit Bagga opened Daryaganj, a restaurant chain in Delhi. Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

The trio behind Moti Mahal eventually retired, selling their empire as a franchise in 1992. As ubiquitous as the dish is, so too is the name Moti Mahal. Thousands of Indian restaurants worldwide bear the name, although they have no affiliation with the original restaurants.

Last year, Jaggi and his childhood friend Amit Bagga opened Daryaganj, a new restaurant chain in Delhi, as a tribute to his grandfather’s legacy and named after the area where Kundan Lal Jaggi opened his first restaurant. Their four venues celebrate north Indian cuisine – including butter chicken – using Kundan Lal Jaggi’s original recipes. Unsurprisingly, butter chicken and dal makhani make up 43 per cent of all orders.

Kundan Lal Jaggi died in Delhi in 2018, aged 94, at peace and out of the limelight, as he would have wanted, his grandson says.

“Everything they [the three restaurateurs] did was out of pure love, ensuring they could share their love and food with the larger community,” Jaggi says. “What fortune my grandfather would have created, what empire he would have set, how the next generation and my generation would flourish, to be honest, he had zero clue.”

Additional reporting by Yang Yang and Bernice Chan

To keep up with demand, the trio opened four venues across Delhi and even ran their own poultry farm, enabling them to acquire up to 600 chickens a day for their restaurants. In the 1950s, then-Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru appointed Moti Mahal as the official caterer of India’s Republic Day, meaning they needed to feed “a few thousand people in a single day”.

Mitra believes the invention of butter chicken was no accident. “He did a massive service to Indian cuisine and he should be celebrated more,” he says.

Mitra still remembers the first time he tried butter chicken as a 12-year-old. It was the first time he had eaten meat, and “the smokiness, the texture and flavour was something totally unique”.

“It was a turning point in my life. I said, ‘I am not going to eat vegetables any more,’” says Mitra, whose restaurants are known for their succulent meat offerings cooked in a tandoor oven.

Palash Mitra cutting up meat for butter chicken at Rajasthan Rifles. Photo: K.Y. Cheng

As chefs from Moti Mahal moved on to work at new restaurants or to open their own, they took the butter chicken recipe with them, says Jaggi – and the dish swept across India.

Mitra says the dish’s global spread coincided with migration of Indian labourers – specifically Punjabis – to the West.

“When they travelled, they took their food with them. You can take the Punjabi away from Punjab, but you can’t take the Punjab out of the Punjabi. So they will create butter chicken anywhere they go,” he says.

“Butter chicken is not the only dish that represents India or Punjabi food, but it significantly demonstrates the culinary history and landscape of the country.”

Last year, Raghav Jaggi (left) and Amit Bagga opened Daryaganj, a restaurant chain in Delhi. Photo: courtesy of Amit Bagga

The trio behind Moti Mahal eventually retired, selling their empire as a franchise in 1992. As ubiquitous as the dish is, so too is the name Moti Mahal. Thousands of Indian restaurants worldwide bear the name, although they have no affiliation with the original restaurants.

Last year, Jaggi and his childhood friend Amit Bagga opened Daryaganj, a new restaurant chain in Delhi, as a tribute to his grandfather’s legacy and named after the area where Kundan Lal Jaggi opened his first restaurant. Their four venues celebrate north Indian cuisine – including butter chicken – using Kundan Lal Jaggi’s original recipes. Unsurprisingly, butter chicken and dal makhani make up 43 per cent of all orders.

Kundan Lal Jaggi died in Delhi in 2018, aged 94, at peace and out of the limelight, as he would have wanted, his grandson says.

“Everything they [the three restaurateurs] did was out of pure love, ensuring they could share their love and food with the larger community,” Jaggi says. “What fortune my grandfather would have created, what empire he would have set, how the next generation and my generation would flourish, to be honest, he had zero clue.”

Additional reporting by Yang Yang and Bernice Chan

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: A legacy to be savoured

Alkira Reinfrank is a digital production editor and reporter with the South China Morning Post, where she also co-hosts the award-winning podcast Eat Drink Asia. Before moving to Hong Kong, Alkira worked as a multiplatform reporter with ABC News and WIN News in Australia. Alkira has appeared on BBC World News, BBC World Service, The Project (Australia), i24 News (Israel) and triple J Hack (Australia).