Monsters by Barry Windsor-Smith – a great, grim slab of postwar angst

This long-awaited epic makes superhuman strength an unsettling backdrop to family drama

There are epic waits, and there’s the wait for Barry Windsor-Smith’s new epic. This great, grim 366-page slab of postwar angst began its life as a Hulk story that Windsor-Smith planned for Marvel in 1984. Now, 37 years later, it finally emerges, its striking cover bearing the ruined face of a man, a Stars and Stripes thrust in one ear, his torn lip exposing a cavernous jaw, a tear trickling from one half-open eye. This is Bobby Bailey, the young man at the centre of this forcefully told and thoroughly affecting drama.

Windsor-Smith’s return is big news. The Londoner got his break after sending sketches to Marvel in the late 60s. He drew staples such as the Avengers and Daredevil, and brought romanticism and style to the award-winning Conan series. But Windsor-Smith has always had his own vision, and his relationship with an industry that has historically kept creatives on a tight leash has rarely been easy. “The business,” he declared in a 2013 interview, “stinks.” In the 70s and beyond, Windsor-Smith spent spells within the industry – writing and drawing the Wolverine origin story Weapon X for Marvel, working on several series for Valiant and creating the Storyteller anthology for Dark Horse – and long stretches out of it. He has published virtually no new work for 15 years; his website’s news section stops in 2011.

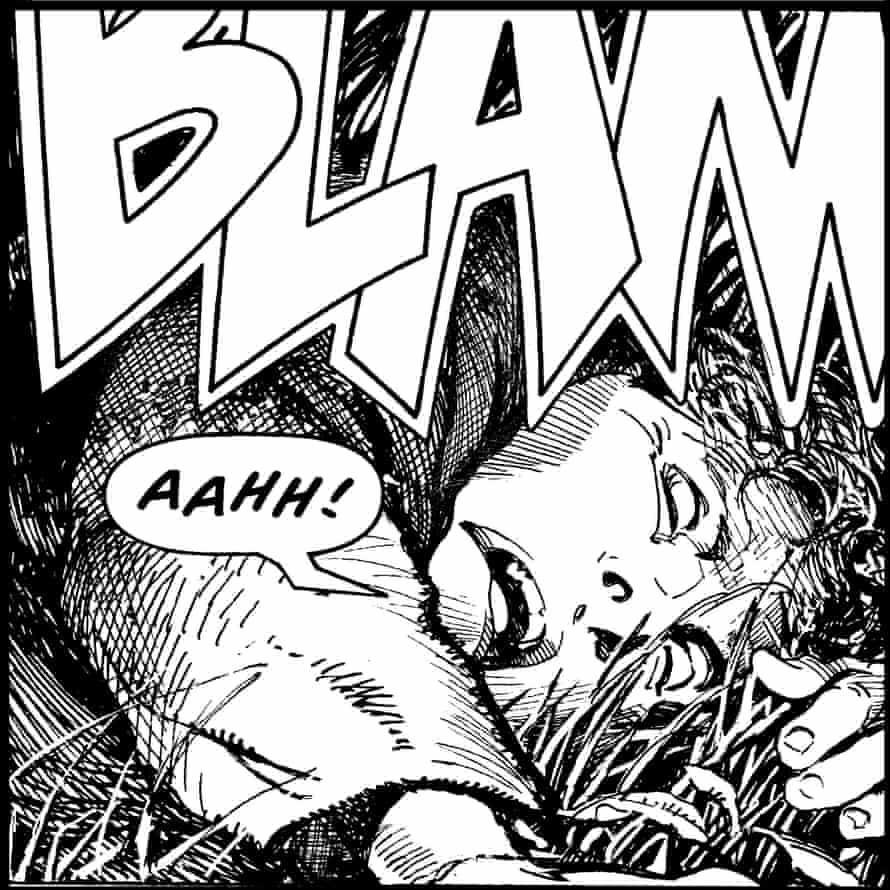

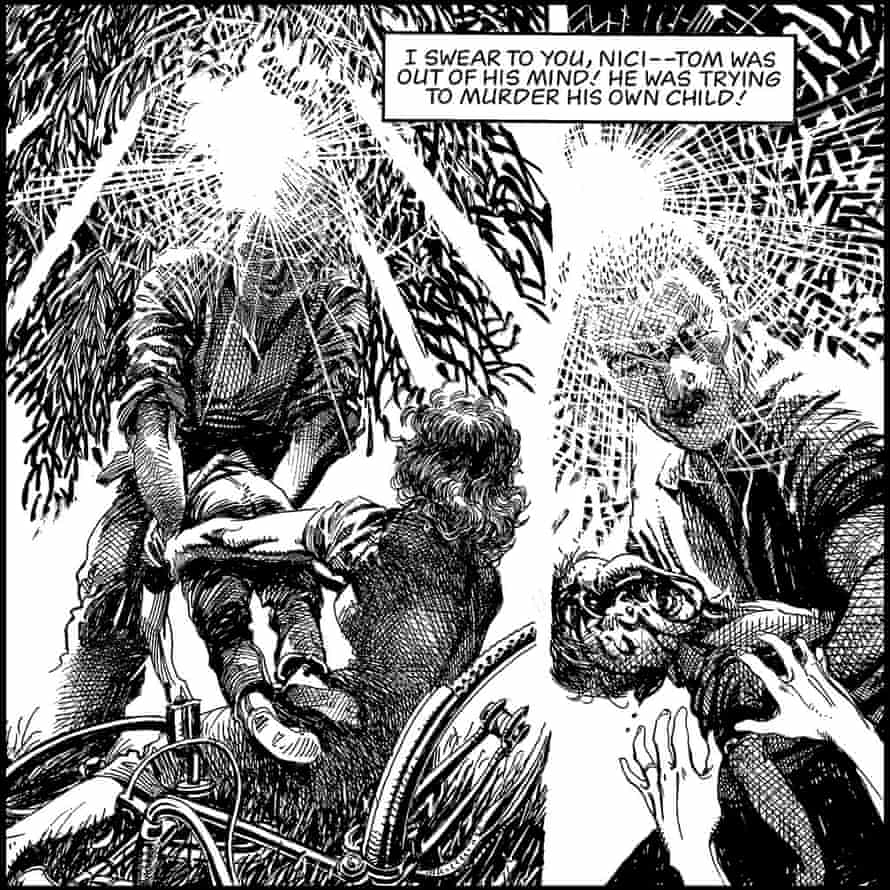

Fittingly, the ambitious Monsters uses time lapses to great effect. It opens in 1949 with brutal violence, as Bobby’s mother, Janet, defends her young son against his raging father, Tom. Fifteen years later, Bobby follows in his veteran father’s footsteps, and walks into an army recruitment office. His claim that he has no family or qualifications sees him chosen for an ominous trial. A few months later, he is dotted with wires and suspended in a stinking pool, his skin swollen with muscles and gouged with scars. His chemically enhanced body is now an army investment, but Bailey has an unexpected ally with an escape plan.

It feels a well trodden set-up, part Captain America, part Frankenstein’s monster. The secret project begins with a Nazi scientist who adjusts his glasses with a claw-hand, while Bailey’s noble saviour is an African American man with “hoodoo” powers. A lesser writer might crank up the cliches another notch, and focus on the violence and drama of a super-soldier on the loose in 60s America. Windsor-Smith does give us shootouts, stakeouts and chases, but Monsters is more interested in turning back the clock. It’s a book about how we got here; a story about a lost boy, his put-upon mother and his brutal, traumatised father, about fraught dinners and PTSD, and about how it takes a monster to make one. And its telling is often brilliant.

Windsor-Smith’s brooding, dramatic panels later show a young Tom and Janet, happy before the war. The new father sends tender notes back from the front, his eye for a scene such that he “could describe the French countryside and the sounds of war in the same sentence”. But after a shock discovery in the chaos of the German retreat, he returns a changed man. The hands that once penned love letters instead reach for the whiskey bottle, and lash out at his wife and son.

Monsters hums with suppressed violence and regret, and Windsor-Smith renders both with real power. His command of pose and gesture – Tom’s thick arms bunching with tension, Janet’s shoulders slumping in resignation – brings his cast to life. Some images stay with you: a bike with buckled wheels in long grass, smoke oozing over a dinner table in an officer’s mess, cross-hatched shadow stretching across a face like a cowl. Alongside the naturalism sits stranger stuff: sausages turn into severed fingers and memories swirl into the present, their echoes turning simple conversations into a deafening hubbub. At the heart of the book, the adult Barry relives his childhood traumas, his great, twisted face and freakish frame balled up on the stairs as arguments burst out around him.

Perhaps inevitably, given its long gestation period and ambitious scope, Monsters can feel disjointed. Its mix of sci-fi, body horror, fateful coincidences, psychic powers and family drama isn’t always coherent; at times the dialogue falls flat. Windsor-Smith’s grotesque visions of butchered cadavers and dark experiments seem distant and almost comedic when set against the real menace and claustrophobia of domestic violence.

Yet that dissonance helps illuminate the book. Pulp fiction has asked again and again what might happen if you could create someone who was more than human. Windsor-Smith’s answer is that such a birth would be a trauma, not the spark for quips and pyrotechnics, but the heart of a very American tragedy. Fittingly for a writer who’s never felt comfortable spending too long in the comics mainstream, he has created a tale in which wild moments of excess and scenes of superhuman strength form an unsettling backdrop rather than the main event. Instead, a family drama of kindness, cruelty and redemption takes centre stage, offering the chance for a broken man to shed his skin, and begin again.

Monsters by Barry Windsor-Smith is published by Jonathan Cape (£25)

No comments:

Post a Comment