After Chile’s November 16th Election: Democracy, Authoritarian Populism, and 35 Years of Unresolved Tensions

NOVEMBER 29, 2025

The left faces immense challenges in the second round of Chile’s presidential election, argues Juan Andrés Mena.

Chile heads to a presidential election runoff on December 14th after no candidate achieved an absolute majority in the first round. This election is not simply another contest between left and right: it is the latest chapter in a 35-year struggle over the meaning of democracy, the legacy of the dictatorship, and the unresolved crisis of Chile’s neoliberal model.

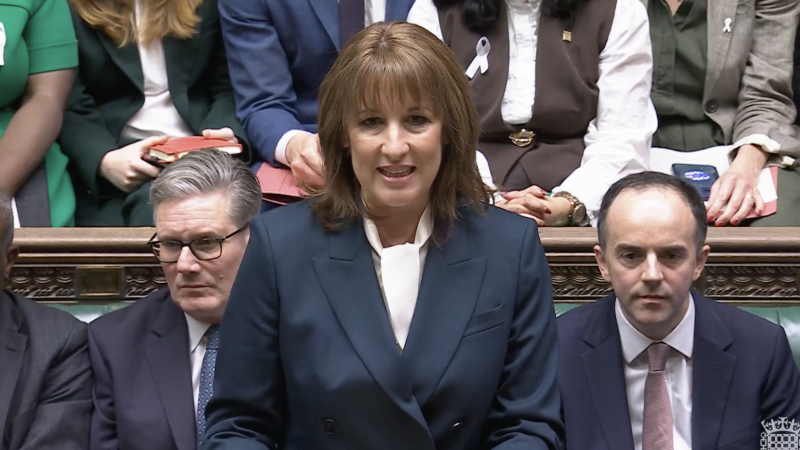

The two candidates who advanced to the next round – Jeannette Jara and José Antonio Kast – represent opposing historical projects. Jara, who obtained 26.8% of the vote, is a lawyer, public administrator, and former Minister of Labour. A moderate member of the Communist Party and winner of her coalition’s primary, she embodies the democratic, institutional path of reform.

Kast, with 23.9%, represents the consolidation of far-right authoritarian populism. His biography is inseparable from Chile’s authoritarian past: son of a Nazi who fled after the war, brother and apprentice of Pinochet’s closets collaborators, supporter of Pinochet in the 1988 referendum, and political heir of the most conservative faction of the dictatorship’s legacy. His third presidential attempt comes after aligning himself closely with Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán.

Behind them, Franco Parisi, a pragmatic, non-ideological outsider, came in third with 19.7%. He was followed by Johannes Kaiser, a disruptive far-right YouTuber with 13.9%, and Evelyn Matthei, daughter of a former member of the military junta and the candidate of the traditional right, with 12.5%. The rest of the candidates barely reached 3% of the votes. Taken together, these results make Kast the clear favourite to become Chile’s next president.

Although these dynamics echo global trends, Chile’s election cannot be understood without situating it within three interconnected historical phases, each with specific political conditions, actors, and grievances that directly shape the 2025 landscape: two decades of neoliberal ‘peace,’ one decade of challenges, and five years of anomie.

Two Decades of Neoliberal ‘Peace’ (1990–2010)

After the coup that ended Salvador Allende’s government, Chile lived 17 years under Pinochet, during which a radical neoliberal experiment was imposed. Guided by the Chicago Boys, the dictatorship transformed the State, privatized social services, and reconfigured politics under a constitution engineered by Jaime Guzmán to preserve this model well beyond the regime’s end.

This is the country that returned to democracy in 1990: an unequal, market-driven society with weak public institutions and an electoral system designed to neutralize change. For 20 years, the Concertación (coalition of parties) governed this inherited model with relative continuity. Despite important democratic advances and reductions in extreme poverty, the coalition did not fundamentally challenge the structure of the dictatorship’s reforms. The electoral system ensured that only two blocs – the centre-left and the right – had representation, generating near-perfect legislative deadlock and making structural reform nearly impossible.

Throughout these two decades, Chile experienced what international observers called the “Chilean Miracle” – an image sustained by a commodities boom and strict macroeconomic discipline. Yet beneath the surface, a fragile society was taking shape. Middle-class families, lacking robust social protections, went heavily into debt to finance education, health care, and pensions – goods provided by a private market that offered no guarantee of quality or security. The first generations retiring under the privatized pension system discovered their savings were insufficient to ensure a dignified old age. A precarious workforce, often trained in low-quality for-profit universities, struggled to find stable employment.

Although these grievances were growing, they did not translate into major political mobilization. Guzmán’s institutional architecture had effectively contained conflict and restricted political imagination.

This period laid the structural foundations of today’s crisis. The unresolved inequalities, social precarity, and weak public services, along with the citizens’ perception of the inefficacy of the political system to solve any of these issues, created fertile ground for both anti-elite outsiders like Parisi and authoritarian ‘law-and-order’ narratives like Kast’s to grow which contributed to the collapse of traditional parties in 2025.

A Decade of Challenges (2010–2019)

The first right-wing government since the return to democracy took office in 2010 under Sebastián Piñera. Within a year, the country erupted. The 2011 student movement – demanding free, high-quality public education – became the largest and most influential social mobilization since the dictatorship. It marked the beginning of a broader cycle of protest that included movements against the privatized pension system, powerful feminist mobilizations, and regionally rooted environmental struggles.

These mobilizations fundamentally changed the political landscape. A new generation of leaders emerged from the streets, including the future president Gabriel Boric, who won a seat in the lower chamber in 2013. Their critique was not simply about specific policies: it was an indictment of the entire post-authoritarian model and the Concertación’s stewardship of it.

Michelle Bachelet’s return to the presidency in 2014 with an absolute majority in Congress seemed to offer a moment of transformative potential. Yet her coalition lacked cohesion, internal conflicts stalled major reforms, and by 2018 the right returned to power with Piñera’s second government.

By then, frustration had reached a breaking point. In 2019, a combination of fare increases, rising living costs and insensitive remarks by authorities ignited nationwide protests of unprecedented scale. Millions took to the streets, demanding dignity and structural change. Piñera declared Chile “at war,” deployed the military – something unseen since the dictatorship – and imposed curfews, further inflaming tensions.

The uprising culminated in the November 2019 cross-party agreement to initiate a constitutional reform process, an outcome previously unimaginable. The decade closed with the political system under profound question, the legitimacy of the post-1990 model shattered, and the party system destabilized.

The decade of challenges produced the new political actors competing today, shaped the left that governs under Boric, and fuelled the polarization that Kast mobilizes. The mistrust toward traditional institutions born in this period is a direct driver of both the rise of the far right and the success of anti-system candidates like Parisi in 2021 and 2025.

Five Years of Anomie (2020–2025)

The years following the uprising were the most turbulent in recent Chilean history. The pandemic exposed the fragility of the privatized welfare system. The first constitutional reform process, despite its democratic spirit, produced a draft heavily criticized for overreach and was rejected by a large majority in a campaign marked by disinformation. A second process, dominated by Kast’s party, ended with another rejection. These failures produced deep exhaustion and disillusionment across the political spectrum.

Gabriel Boric’s 2021 victory – achieved with the highest turnout since 1990 – was largely the result of massive democratic mobilization against Kast, rather than a direct support for Boric. Thus, once in office, Boric confronted a fragmented Congress and required an alliance with the same former Concertación he had once harshly criticized. This forced pragmatic compromises that disappointed parts of his base and reinforced a sense that democratic institutions were incapable of solving people’s problems.

Politically, the right underwent a dramatic transformation. The death of former President Piñera in a helicopter accident symbolized the end of the ‘democratic right’. Similar to the 2021 election, in the 2025 first round, Kast and Kaiser decisively outperformed Evelyn Matthei, signalling the definitive collapse of the traditional right and the rise of a new authoritarian populist bloc.

A decisive turning point was the introduction of compulsory voting, which brought nearly 13.5 million Chileans – 52.5% more than the previous election – to the polls. Many of these new voters were politically distant, economically insecure, and distrustful of institutions. They became the main reservoir of support for Franco Parisi, who ran once again as an outsider, and for Kast, whose fundamentalist conservatism and authoritarian discourse resonated with demands for order and restoration amid chaos.

This period directly shaped the conditions of the first round: a vastly expanded electorate, a challenged new left and weakened traditional one, a discredited, almost non-existent centre, and a far right that has successfully redefined itself as the champion of order and stability to the detriment of the traditional right.

November 16th: A New Political Map

The first round of the 2025 election produced unprecedented outcomes. With the highest participation in Chile’s history under democracy, voters delivered several clear messages.

First, the traditional right collapsed, replaced by a consolidated authoritarian-populist right led by Kast. Matthei, considered Piñera’s political heir, was decisively overtaken by Kast and Kaiser, confirming that the historic centre-right no longer has a social or ideological base.

Second, Franco Parisi, running on a platform mixing anti-communism, anti-Pinochetism, and anti-elite resentment, captured a significant portion of the newly incorporated electorate. He even surpassed the left in regions historically associated with left-wing voting patterns.

These results reveal a new cleavage replacing the old democracy-versus-dictatorship divide that dominated Chilean politics for decades. Today, the electorate is split between an authoritarian-populist right offering order, identity politics, and punitive solutions; a large, volatile anti-elite, ideologically diffuse segment worried about insecurity and the cost of living; and a democratic left struggling to reconnect with disillusioned citizens.

The runoff between Jara and Kast is thus not about typical left-right competition. It is the crystallization of the long-term contradictions of Chile’s post-authoritarian trajectory. Kast represents the reaction to three decades of unresolved social tensions, institutional fragility, and disillusionment with democratic governance. Jara embodies the attempt to salvage democracy by addressing these grievances without renouncing pluralism.

The 2025 election is the culmination of 35 years of accumulated tensions. The neoliberal ‘peace’ created the inequalities, frustrations, and institutional constraints that later exploded. The decade of challenges delegitimized the post-1990 order and birthed new political actors. Yet it was unable to produce a new order capable of replace the existing one, satisfying the historically postponed social needs. The years of anomie fractured institutions, exhausted citizens and opened the door to authoritarian populism.

If the left wishes not only to win but to survive, it must defend democracy while confronting the demands of those who have lost faith in both the political system and in democracy as a tool for solving their daily problems. The challenge is immense, but so are the stakes: the future of Chile’s democratic path itself.

Juan Andrés Mena is a lawyer, MA in Public Policy, and researcher at Nodo XXI.

Image:Jeannette Jara, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Live_Especial_Mujeres_Comit%C3%A9_Pol%C3%ADtico,_Ministra_Jannette_Jara_%28crop2%29.jpg.

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/secretaria_general_de_gobierno/52354955101/. Author: Vocería de Gobierno, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Friday 28 November 2025, by Karina Nohales, Pablo Abufom

Everything indicates that Chile will be governed for the next four years by a coalition of right-wing parties, headed by one of its most extreme factions, with José Antonio Kast at the helm. That right wing —Pinochetism— has existed in the country for decades, but for the first time it would come to power through elections, with the support of popular sectors and in an international context marked by the global advance of far-right forces.

The election results of Sunday, November 16, clearly demonstrate the magnitude of the right-wing victory. In the presidential election, the right-wing bloc garnered 50.3% of the vote, distributed among José Antonio Kast (23.9%, Partido Republicano or Republican Party), Johannes Kaiser (13.9%, Partido Nacional Libertario or National Libertarian Party), and Evelyn Matthei (12.5%, Chile Vamos or Let’s Go, Chile).

At the same time, the right wing is consolidating its majority in Congress. Of the 155 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, the sector already aligned with Kast holds 76, compared to the 64 held by the left and centre-left. In the Senate, the right-wing bloc controls half of the seats.

If we take into account that the Partido de la Gente or Party of the People (PDG) won 14 seats in the Chamber, everything indicates that the right wing in government will be able to form a parliamentary majority capable of reaching even the 4/7 needed to promote constitutional reforms.

In this context, the traditional right wing —the Unión Demócrata Independiente or Independent Democratic Union, Renovación Nacional or National Renewal and Evolución Política known as Evópoli or Political Evolution, grouped in the Chile Vamos coalition— ends up aligning itself behind Kast after an internal dispute for the leadership of the sector and after suffering a resounding defeat. Their presidential candidate came in fifth, behind all other right-wing candidates; the bloc went from 12 to 5 seats in the Senate and from 52 to 23 in the Chamber of Deputies, and one of the coalition parties was dissolved.

Far from any policy of "cordon sanitaire" —such as those implemented by liberal-conservative sectors in other countries to isolate the far right—in Chile the traditional right maintains historical and organic ties with Pinochetism. This connection explains its rapid subordination to Kast’s leadership in the current political cycle.

Meanwhile, the official candidate Jeannette Jara —nominated by the Unidad por Chile or Unity for Chile pact and from the Communist Party — won by a narrow margin in a campaign that, despite being the only progressive candidacy, was not a left-wing campaign. The 26.7% she obtained fell short of the expectations generated by her position as Minister of Labour and even below the 38% that supported the 2022 constitutional proposal.

It is true that Jara faced an adverse scenario: an unfavourable international situation, the strain of being part of the ruling party at a time of widespread challenge, and the weight of an effective anti-communist narrative. But it is also true that neither the government nor the candidate developed a policy aimed at confronting the extreme right. On the contrary, in sensitive areas such as migration and security, they chose to appropriate part of the narrative and programme of their adversaries. She also made no attempt to distance herself from the persistent neoliberal consensus that all institutional forces have embraced since the defeat of the constitutional proposal in October 2022, beginning with Boric’s own government. This is one of the clearest expressions of the far right’s advance: it not only persuades the electorate but also manages to impose its political agenda across the board.

The surprise from the first round of the presidential election was the 19.7% obtained by Franco Parisi, candidate of the PDG, a party that appeals to the aspirations of middle sectors through a combination of monetary populism, securitised xenophobia and crypto-digital rhetoric against corruption and the "privileges" of public officials. Although all the polls placed him fifth, he finished third, ahead of Kaiser and Matthei. In his third presidential bid, Parisi tripled his 2021 vote and won the most votes in all four northern regions, a key mining area marked by a widespread anti-immigration agenda due to its border location through which migrants from the rest of the continent enter. Parisi has thus become the main source of votes that Jeannette Jara will try to capture, something she made explicit in her speech on the evening of Sunday, November 16.

Initial analyses show a marked territorial division of the vote. A report from the Faro UDD think tank shows that Parisi triumphed in the "mining north" (regions of Arica, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, and Atacama), Jara obtained a majority in "central metropolitan Chile" (Metropolitan and Valparaíso Regions, as well as the far south of Aysén and Magallanes), and Kast dominated in the "agricultural south" (O’Higgins, Maule, Ñuble, Biobío, Araucanía, Los Ríos, and Los Lagos).

This fragmentation is also socioeconomic. A particularly critical piece of data for the government candidate is that her performance in low- and middle-income municipalities was worse than in high-income ones, a trend opposite to that of Kast, whose vote increased in lower-income municipalities and fell in wealthier ones. These differences are even more significant when you consider that voting was mandatory in the election and had a participation rate of 85% of registered voters, the highest since 1989.

Another relevant fact for the scenario that opens up for the second round and for the next government is that, of the 25 parties legally constituted at the time of the election, 14 are to be dissolved under the Political Parties Law, which requires a minimum of 5% of the votes in the last election of deputies or, alternatively, obtaining at least four elected parliamentarians in two different regions. Of the 14 parties that will disappear, 8 are left-wing, 4 centrist, and 2 right-wing. The result is conclusive: after this election, all left-wing parties outside the governing coalition are legally dissolved. One of the causes of this debacle is the inability to build a unified list in an electoral system —based on the D’Hondt method— that rewards pacts and severely punishes dispersion, since the most voted lists attract candidacies that, even with equal or greater individual support, are left out if they compete in isolation.

Political processes—including electoral ones—have a direct impact on collective emotions, and today that impact is expressed in a strong disillusionment within the left-wing forces. We also know that the social and electoral rise of the far right is not an exclusively Chilean phenomenon. It has occurred with Bolsonaro in Brazil, it is happening with Milei in Argentina, and in the United States with Trump. This present moment demands that we learn from the experiences of the people and left-wing movements that have already weathered the reactionary advance from within the government. Not all trajectories are the same, but internationalist dialogue is a necessary condition for understanding the tasks that lie ahead in the next political cycle and in the face of the most likely governing scenario.

In the immediate future, with the second round of the presidential election on December 14th approaching, it is worth asking whether the margin by which Kast may win is irrelevant or not. Calling for a vote for Jara means explaining why we do so even while holding a deeply critical view of her and her millieu, and why we do so even knowing that it’s an election that will likely be lost. It’s not that difficult: after all, a policy of radical transformation almost never starts under favourable conditions, and yet we persist in it.

The first political task of this situation is to deploy an anti-fascist pedagogy that reaffirms the importance of putting all our vital forces into preventing the most extreme version of the programme of exploitation from being imposed without counterweight and without resistance. It is essential that those who feel discouraged today can consciously come together for shared reflection and a call to resume organising and mobilising. To build a broad base of opposition to the future far-right government, it matters how one loses: it is necessary to lose with one’s head held high and with the greatest possible strategic clarity.

The recovery of our strength along with the construction of a response to the crisis from the point of view of the working class — in opposition to both emboldened fascism and bankrupt progressivism — will require serious programmatic work, which must be developed within the collective action of popular movements, and not only in progressive think tanks or from opposition parliamentary benches. Faced with the conservative, authoritarian, nationalist, patriarchal, and capitalist program of the Chilean right, popular movements will have the responsibility to become the first line of defense and the main trench from which to organise a counter-offensive.

November 18, 2025

Translated by David Fagan for International Viewpoint from Revista Jacobin.The article is part of the series Latin American Situation and Argentine Elections 2025, a collaboration between Revista Jacobin and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Attached documentsfrom-progressive-decline-to-reactionary-advance-in-chile_a9282.pdf (PDF - 914.1 KiB)

Extraction PDF [->article9282]

Chile

After the 1973 Coup in Chile

The coup in Chile

The Chile Coup and after

The rising class consciousness of the proletariat and the problem of power

Debate on the counter revolution in Chile (1973)

Karina Nohales is a lawyer, member of the Chilean Committee of Women Workers and Trade Unionists and the Internationalist Committee/March 8 Feminist Collective. She is in the editorial collective of Jacobin América Latina

Pablo Abufo is Editor of Posiciones, Revista de Debate Estratégico, founding member of Centro Social and Librería Proyección and part of the editorial collective of Revista Jacobín.

International Viewpoint is published under the responsibility of the Bureau of the Fourth International. Signed articles do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Articles can be reprinted with acknowledgement, and a live link if possible.