Nuclear Weapons In Space: Orbital Bombardment And Strategic Stability – Analysis

September 25, 2025

Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Aaron Stein

Introduction

(FPRI) — The American scientific community was in “awe” on October 4, 1957. The Soviet Union had defied expectations and launched the satellite Sputnik 900 kilometers above the earth’s surface. The launch had ominous overtones: The Soviet Union used an intercontinental range ballistic missile to launch a satellite into orbit and the foreign body circled the earth 1800 times before falling back to earth and burning up in the atmosphere.

In 1957, the Soviet Union was the world’s space pioneer. Moscow recognized the value of space and invested considerable resources in beating the United States into orbit. The launch of Sputnik kicked off the space race, which culminated in America’s dash to the moon, and continues with the rapid – and unprecedented – breakthroughs now being witnessed in the private sector.

Humanity’s exploration of space has pushed the boundaries of science since the start of the rocket age. It has also blurred the lines of peace and war. Sputnik was a civilian satellite, designed for prestige and to carry out scientific experiments. It was also a technology demonstrator for intercontinental nuclear war. The Eisenhower administration understood its political vulnerabilities and sought to downplay the Russian achievement. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev did not and continued to boast that his country had a technological lead over the United States in rocketry and ballistic missiles.

Space technology is inherently dual-use: The platforms used to launch satellites can also be used to deliver atomic weapons. The same is true of defenses: The things built to shoot down incoming missiles can also be repurposed to shoot down satellites. The tensions between offense and defense have dominated how the United States has sought to manage access to space. On the one hand, space is a global common, and nations that make appropriate investments in rocketry and flight can one day take advantage of it. Yet, on the other hand, access to space is required to launch nuclear weapons trans-continental distances, supported by imaging and reconnaissance satellites that the entirety of the modern kill chain is now dependent on.

The Soviet Union pioneered novel and unique ways to hold U.S. space-based assets at risk. China is now following suit. The United States did dabble in the development of anti-satellite weapons, launching the world’s first direct ascent anti-satellite missile in October 1959. Moscow’s response, in retrospect, set in motion the drivers of the space race that is now threatening to return. In 1961, purportedly in response to U.S. actions in space, Khruschev directed his government to expand work on the militarization of space.[1]

In the early days of the Cold War, the superpowers’ conquering of the cosmos helped enhance deterrence. Both the United States and the Soviet Union focused, first, on developing reconnaissance satellites, followed by early warning satellites designed to monitor missile launches, and then integrated both into their monitoring of each other’s nuclear forces.

The basic idea of deterrence is mutual vulnerability, specifically that no side has an incentive to use nuclear weapons. Instead, a first strike would invite guaranteed retaliation, which in the aggregate would lead to a sub-optimal outcome for the first attacking state, thereby disincentivizing any nuclear power from launching first. To ensure that this balance remained in place, a defending state would need to ensure a second-strike capability. To enhance stability, it made sense for each side to watch the other and increase predictability.

The development of reconnaissance satellites allowed for each side to monitor the other, which added transparency to the type and number of nuclear forces each side was deploying. In the 1970s, the ability to monitor one another from space allowed for each side to agree to forego the deployment of military technology or limit the type and number of deployed systems.[2]

The pursuit of arms control, as John Maurer notes, was not solely some altruistic attempt to make the world safer. Instead, it was part of a series of offset strategies, designed to account for how the United States could retain military superiority over the Soviet Union, even at a time when Moscow had pulled even with the United States in terms of total numbers of nuclear warheads deployed. The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty was a lynchpin of this strategy. It was designed to cap the number of deployed anti-ballistic missile interceptors around Moscow. For Russia, it capped U.S. deployments, locking in a sense of mutual vulnerability that helped to enhance deterrence.

The Soviet Union, however, continued to test the limits and spirit of the arms control treaties it signed. The period of détente did not hinder Moscow’s interest in the militarization of space and the continued development of orbital platforms to evade U.S. early warning and nascent missile defense architecture.[3] Instead, Soviet designers continued to develop new and innovative ways to attack U.S. satellites and to deliver nuclear weapons to the U.S. homeland. Moscow also views international agreements as tools to add to national power. The Soviet leadership was not constrained by either the Outer Space Treaty or the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) when testing space-based weapons and new classes of medium-range missile.

This study will examine the new dynamics in space. For decades, government was the main driver of space innovation. Over the past two decades, the traditional way in which space technology is developed and launched has changed. The rise of companies like Blue Origin and SpaceX has completely altered the economics of space and has revolutionized how goods and humans are sent to the heavens.

The rapid decrease in the cost of launch and satellite construction has increased global connectivity, improved the global economy, and has changed the world profoundly. The growing use of space has also heightened efforts to further militarize the cosmos and creates an obvious incentive for American adversaries to explore ways to hold at risk orbiting constellations with nuclear weapons.

The U.S. military has long depended on space-based capabilities, with that dependence set to grow. The war in Ukraine has demonstrated the value of the commercial Starlink constellation, led to the development of the national security Starshield version, and probably also spurred Russia’s development of orbiting nuclear weapons to mass-kill smallsat constellations in the event of a wider war with NATO. The promise of decrease launch costs from SpaceX’s planned Starship also makes space-based missile defense more economically viable than ever, raising again the promise of novel ways to evade missile defense. China demonstrated one such technique in August 2021, when it tested an orbital bombardment system.

The United States has considerable opportunities to take advantage of this new space age. Its industry is far ahead of any competitor. The rapid decrease in launch costs will undercut Russia’s launch services industry, depriving its competitor of potential funds. However, U.S. adversaries will not simply sit back and let Washington retain such advantages unchallenged. The incentives for an adversary to develop anti-satellite weapon and orbital bombardment systems are considerable. There are also ample incentives for Russia to push ahead with a nuclear-armed, co-orbital anti-satellite weapon. However, with each such deployment, U.S. adversaries may also face weaknesses that, if exploited by proper investments, could ensure the United States retains its enviable lead in space launch capabilities and burgeoning space-based missile defense.

Circumvention and Hedging: Soviet Practice in Space

The Soviet space program provides a useful guide about how Moscow has historically sought to circumvent treaty agreements to gain military advantages vis-à-vis the United States. For much of the Cold War, the Soviet Union had fewer nuclear weapons than the United States. However, both sides have used mutual restraint to their advantage. The Soviet Union sought and received limits on American missile defense with the signing of the ABM Treaty, as part of the SALT I agreements.

Almost immediately, however, Russia violated the spirit of the agreement with the development of a Fractional Orbital Bombardment System, or FOBS. Moscow officially pledged not to place nuclear weapons in orbit when it agreed to the Outer Space Treaty in 1966. Article IV of the agreement clearly states that state parties “undertake not to place in orbit around the earth any object carrying nuclear weapons.”[4] The Soviet Union then promptly violated the spirit of the treaty. At the dawn of the missile age, Soviet planners viewed orbital weapons as potentially superior to missile-launched warheads. Military planners correctly argued that an orbital weapon would have an unlimited flight range, be able to strike targets simultaneously from two different directions, have unpredictable trajectories and faster flight times to targets. These advantages would obviate any advantage a defender could gain from missile defense, thereby ensuring the credibility of a retaliatory nuclear strike.[5]

At the dawn of the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union explored orbital bombardment concepts. The idea is that you can place something in orbit and, after a fraction of an orbit or a total orbit around the earth, it can then be de-orbited to strike targets on the ground. Orbit is a state of being. An object placed in orbit is moving fast enough that it continues to fall over the horizon faster than it does back to earth. To come back to earth, an object in space must slow down. This is how a FOBS would work: An object is inserted into orbit and then fires a small rocket to slow down and fall to its target. One advantage of such a system is that you do not have to fire a missile on a ballistic arc, therefore decreasing early warning time for the defending state. The other advantage is that an attacking state could insert an object into orbit over Antarctica (flying south) and have the object “take the long way around” the earth. This object then would avoid U.S. early warning radar and missile defense tracking, which remain pointed at the North Pole (the shortest distance between the United States and Russia and China).

In retrospect, Moscow’s interest in the ABM Treaty makes more sense. The Soviet Union agreed to place reciprocal limits on missile defense deployment. It did so knowing that it had other tools to hedge against any qualitative advancement in U.S. missile defense interceptors and that it could still hold at risk U.S. targets with nuclear weapons deployed in exotic ways.

The Soviet Union tested and deployed this FOBS in 1967, just months after the leadership in Moscow signed the Outer Space Treaty. The United States chose to accept the Soviet legalese explaining away the violation: The weapon did a fractional orbit but the treaty ostensibly only covered a full orbit, thereby giving some wiggle room to President Lyndon Johnson to ignore the violation.[6] The Soviet FOBS system remained operational for close to two decades, before being dismantled in 1983.

As we look back at the early days of the space race, the paranoia about Sputnik is often how Americans frame the U.S. government’s subsequent effort to conquer the cosmos. However, in Moscow, a similar paranoia had taken hold and drove its own ambitions in space. In a forgotten part of the early Cold War, the Soviet Union shot down numerous American surveillance aircraft over the Baltic Sea and over Hokkaido in the Pacific between 1950 and 1952.[7] Moscow’s belligerence prompted American innovation, sparking the development of the U-2 aircraft in 1954. The use of the U-2 to overfly the Soviet Union prompted Moscow’s push for more capable air defense, ending in the shooting down and capture of Francis Gary Powers in 1960.

The U.S. response, as is now well known, was to push forward with the development of reconnaissance satellites. Moscow noticed. In 1959, according to Dr. Asif A. Siddiqi, “Khruschev was reportedly personally upset over the possibility of ‘spy’ flights over the Soviet Union” and directed scientific and military personnel to develop the means to identify hostile satellites and to shoot them down. Shortly thereafter, in early 1960, Moscow settled on co-orbital maneuvering satellite that could hard kill satellites in orbit.[8] The Soviets envisioned, at first, this satellite carrying a nuclear warhead, but after studying the effects of nuclear explosions in space, scientists concluded that the blast was indiscriminate. Put simply: It would kill both American and Soviet satellites by frying their electronics.

The United States had reached the same conclusion as their Soviet counterparts. Following the Starfish Prime high-atmospheric nuclear test in 1962, the radiation level in the Van Allen Radiation belt increased. As Robert Vincent wrote in War on the Rocks:

The Van Allen radiation belts perform a crucial task of sweeping charged particles from the sun away from Earth to create a shield against charged particle radiation from low Earth orbit to the surface (below 1,000 kilometers in altitude). … commercial satellites in low Earth orbit take full advantage of the reduced particle radiation and may incorporate standard commercial electronics into their payloads. The use of these components sharply reduces costs.[9]

As a result, the world’s first commercial communications satellite, Telstar, lasted only 8 months in orbit before the residual radiation from the Starfish Prime test destroyed its electronic components.[10]

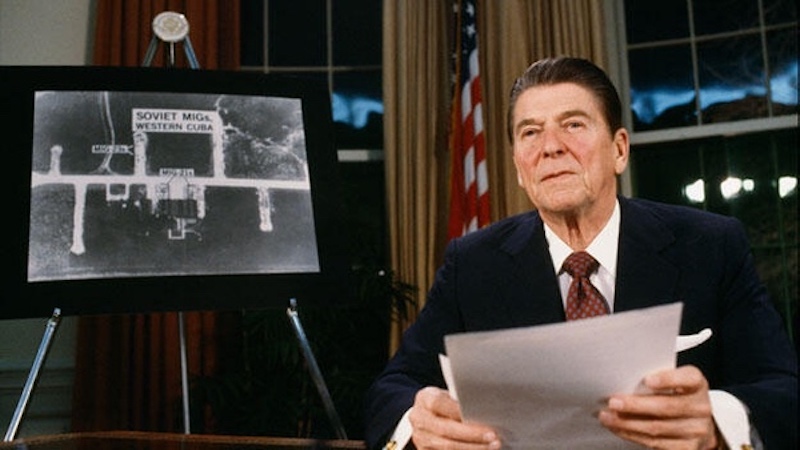

The Soviet Union settled on a conventional payload for its co-orbital satellite in response because of its own desire to protect its satellites in orbit. In the mid-1970s, it ramped up experiments of exo-atmospheric interception, which culminated in the first single orbit interception in 1976 – a milestone for the project. This period in Soviet space history is often overlooked. A half-decade before President Ronald Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), the Soviet leadership issued a decree to establish Fon, a program to develop orbiting lasers and missiles. The ambitious program was designed to attack orbiting satellites, rather than missiles, and was pursued with some ambition for close to a decade.[11] This program was beset by funding challenges, but a prototype was launched into orbit at the tail end of the Cold War.

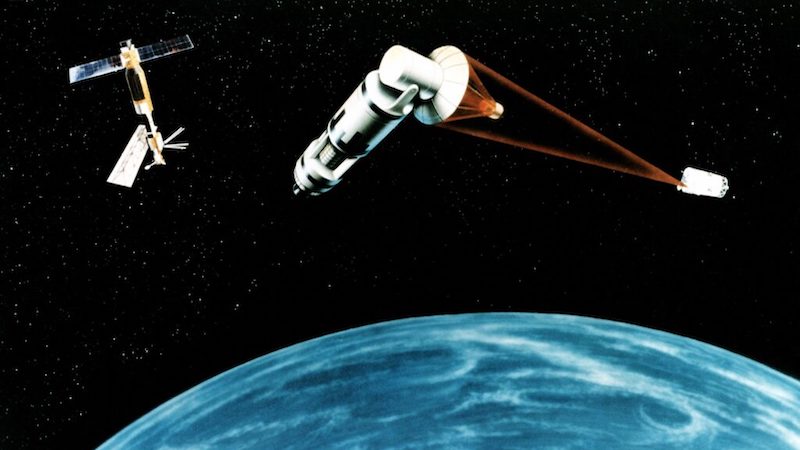

SDI codified U.S. policy in space. After decades of seeking to carve out a passive role for satellites, and therefore pushing the Soviets to agree to peaceful use of space, the Reagan administration pushed forward with an ambitious plan to overtly defend U.S. territorial interests with space-based assets. The Reagan administration’s pursuit of space-based missile defense was controversial – and continues to be to this day. However, the investments made in rocket technology has contributed to the development of the technology that has revolutionized space flight over the past decade. The basic idea of SDI was to build missile interceptors in space, capable of tracking and then striking missiles while they are being boosted into space. The program would require a radical leap forward in technology and major advances in rocketry to bring the cost of launch down considerably. The basic challenge with SDI is that the number of satellites required to protect the United States is considerable and the cost to launch each satellite also very high.[12] This made the project infeasible from an economic standpoint and the technology required was simply not mature enough during the program’s lifetime to deploy the entirety of the system.

The Soviet Union did seek to compete with SDI, matching the program’s ambitions with design-bureau led efforts of its own. However, in retrospect, the program’s launch coincided with the Soviet Union’s rapid decline. Moscow was simply unable to compete with the United States on a spending level during this period. Thus, while the Soviets clearly had the ambitions to match the United States in space, and had invested heavily in the militarization of space, the program atrophied alongside the decay of the Russian state. The final days of the Soviet Union coincided with Operation Desert Storm, the first true test of American-led doctrine pitted against a Soviet armed state, Iraq, outfitted with the latest air defense Moscow had to offer.

The rapid defeat of Saddam Hussein, primarily with air power, appeared to validate the Soviet concerns, first articulated in the 1970s, about the lethality of U.S.-made precision-guided weapons. These weapons, according to Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, could upend Soviet assumptions about ground combat and required rapid change within the Soviet armed forces to plan for future conflicts.[13] The so-called revolution in military affairs codified the success of the second offset. It also depended considerably on the connectivity of communications for almost all aspects of joint warfighting.

In the decades since the war, the United States has iterated on the lessons learned from the conflict, further deepened its reliance on precision weapons, and created a surveillance architecture to monitor combat zones around the world. The development of uncrewed platforms has contributed to this evolution – and those platforms are dependent on satellite communications to connect war planners in Washington with operators in theater.[15] U.S. adversaries also studied closely the lessons of the Gulf War and the follow-on air campaigns in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, and Iraq. The Russian and Chinese governments have, ever since, invested in weapons to offset U.S. advantages. They have also developed doctrines to challenge the American way of war. China, as Peter Mattis writes, is a good example of how observations informed the party’s thinking about conflict and coalesced around a “three warfare” concept. According to Mattis:

From the Gulf War onward, analysts in the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] saw a trend they described as “peacetime-wartime integration.” Victory in war, or at least achieving one’s political objectives, increasingly depended on the preparations made in peacetime. Success required shaping how other governments and their people as well as one’s own population viewed the conflict. Information operations needed external and internal dimensions … The importance of this trend was amplified by the ‘conventionalization of deterrence’.[16]

The focus on both influence operations and conventional weapons is instructive. It suggests a synergy between both the Russian Federation and Chinese Communist Party about basic concepts for war with the United States. These broad synergies do not necessarily lead to the same preferred tactics, but they do suggest a lesson incorporated from U.S. action in Iraq: the disruption of command and control with conventional attack.

This approach was the centerpiece of the American war effort against the Iraqi government. It was an attack on the Iraqi command-and-control infrastructure, following a months-long psychological warfare effort to convince individual Iraqis to capitulate and turn on Hussein. The air campaign worked well. The psychological campaign, perhaps not so much.[17] However, in both the Russian and Chinese cases, the appeal of such an approach is easy to understand: A conflict could be kept below the nuclear threshold, with the threat of nuclear escalation used as a mechanism to limit potential U.S. involvement in a localized territorial conflict. In extremis, both countries have sought to limit the potency of American aerospace attack. Russia has fallen back on its traditional approach to such a contingency: investing in air and missile defense, coupled with the development of a range of nuclear delivery systems to hold U.S. and Western targets at risk. In times of war, Russia has brandished its nuclear sword to deter U.S. involvement, albeit to varying degrees of success.[18] China has sought to physically change the space around it. It has built artificial islands. It has invested in longer range weapons to hold U.S. air and sea-based targets at risk at greater ranges. It has also recently invested in upgrading its nuclear forces, a signal that Beijing may consider using a larger arsenal to protect itself from future U.S. missile defense deployments and to sue for war termination on favorable terms.

These trends in Chinese and Russian military adaptation have had a direct impact on their approach to space warfare. The other part of these operations – hindering U.S. command and control – is also central to future contingencies. And it helps explain both countries’ aggressive return to the development and deployment of ground-based anti-satellite weapons.

Challenging U.S. Supremacy in the Heavens

In 2007, a Chinese ballistic missile fired from earth smashed into a satellite orbiting at the upper boundary of low earth orbit. The anti-satellite test destroyed its target and created nearly a thousand pieces of debris.[19] The test was not a shock for U.S. intelligence, which had warned consistently since 2003 that Beijing was working towards this type of capability. A Chinese analyst, writing at the time suggested that the test to enhance Chinese nuclear deterrence. A PLA colonel, writing months before the test, suggested that China needed an anti-satellite capability to challenge the United States in space. [20] The test was a watershed moment for U.S. security planning and thinking about operations in space. In response, the United States sought to demonstrate to China that it too could target satellites in space, ostensibly to prevent the uncontrolled reentry of a defunct satellite back to earth. However, the 2008 shootdown of a U.S. satellite with a modified SM-3 missile undoubtedly signaled that U.S. capabilities were on par, or greater than, those of its adversaries.

The SM-3 is the backbone of the U.S. missile defense architecture in Europe. It also underscores the undeniable linkages between hit-to-kill missile defense interceptors and direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons. In the 2004, the Bush administration set aside funds for the construction of a limited missile defense system. This decision came after the United States chose to withdraw from the ABM Treaty in 2002. The administration argued that the United States should develop ground and sea-based mid-course missile defense interceptors, along with updated terminal defenses, and a slew of new tracking satellites to defend the homeland from attack.[21] The inclusion of this language in the nuclear posture review, I believe, is why Chinese experts explicitly linked the 2007 ASAT test to its own nuclear deterrent. It also explains why adversaries would seek to blind U.S. sensors. The shooting down of a satellite would, of course, both hinder operational command and control for the U.S. military and blind early warning sensors, upending elements of U.S. missile defense, and enhancing the survivability of nuclear forces.

Russia pursued a slightly different strategy, albeit in cooperation with China. The Russian Federation faced economic calamity after the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, by 1999, the early signs of the breakdown of the post-Cold War order were evident. In response to Serbian ethnic cleansing, NATO began airstrikes in Kosovo. Russia vehemently protested the intervention, arguing that the United States’ power to intervene needed to be constrained, and litigated through the U.N. Security Council. The relationship was temporarily reset after the September 11, 2001 attacks, but quickly soured over the issue of missile defense in Europe.

The real turning point for Russia came in 2007, when President Vladimir Putin articulated the same concerns about the international community that his predecessors first began to raise in 1999. Putin suggested that the only international arbiter for the use of force should the United Nations – and not solely NATO or the European Union. He also created the groundwork for his future military invasions of his neighbors. He warned against inviting Ukraine and Georgia to join NATO and, critically, outlined his objections to the Bush administration’s pursuit of missile defense:

it is impossible to sanction the appearance of new, destabilizing high-tech weapons. Needless to say it refers to measures to prevent a new area of confrontation, especially in outer space. Star Wars is no longer a fantasy – it is a reality.[22]

Months later, Putin sanctioned the invasion of Georgia. Russia won the war, but the Russian performance on the battlefield was lacking.[23] In response, the country’s armed forces were reorganized and, importantly, a major rearmament plan was created to modernize the armed forces by 2020.[24] In retrospect, this was the start of a Russian military build-up that culminated in the second invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Thus, by 2009, the United States was staring down two adversaries that had made the strategic decision to build up their armed forces. China had started this process far earlier than the Russian Federation. The United States, in contrast, was still operating under assumptions from the post-Cold War era. Washington was distracted by two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and its efforts to counteract the build-up of these two powers only just began in or around 2022.

Novel Weapons, Nuclear Taunts, and the New Space Race

In 2015, a private company achieved a longstanding goal. A rocket built by Blue Origin landed gently back on the pad after launching 100 kilometers into space.[25] A month later, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket did the same. The technologies that may make this renewed effort more financially feasible all began as offshoots of the Reagan-era missile defense program. One such program, was the DC-X Clipper, which was part of the decades-long effort to build a single-stage to orbit launch platform to decrease the cost of vertical launch. This technology remains elusive, but the next best outcome is to reuse the booster. The results have made the concepts underpinning space-based missile defense more economically feasible than at any other point in human history.

The company has been able to perfect its Falcon launch system, reusing boosters and dramatically lowering the cost of launch. In the near future, the planned development of Starship – the world’s largest rocket – promises to further decrease costs. This rapid cost decrease enables human progress, particularly around communication and the launch of large numbers of satellites. SpaceX’s cost per kilogram launched is estimated at approximately $200. The Space Shuttle’s cost per kilogram launched was approximately $30,000.[26] The decrease in cost has enabled the launch of large constellations, now devoted to internet services, communications, and imagery. The same technology could be used to launch thousands of space-based interceptors, a concept that Reagan kicked off with SDI and President Donald Trump is now pursuing again as “Golden Dome.” The economics of space-based missile defense is now more favorable than ever before. It is no longer “economic fiction” to conceptualized large satellite constellations, orbiting the earth constantly and launched on demand via an efficient and proven booster.

In late 2019, Russia shifted its own operations in space. The United States accused Moscow of launching a single satellite that settled into the same orbit as a U.S. imaging satellite. The Russian satellite then released a second satellite, which could maneuver in orbit and get even closer to U.S. surveillance satellites.[27] A maneuvering co-orbital satellite is exactly what the Soviet Union built and tested in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Russia’s return to this technology, therefore, signaled an intention to revive dormant programs, presumably with the same intent: to integrate anti-satellite operations into nuclear war planning.

It is worth examining how the Soviets thought about the linkage between ground based anti-satellite weapons, missile defense, offensive nuclear strikes, and co-orbiting anti-satellite weapons. The Soviets conducted exercises as late as 1982 with simulated strategic and medium-range missile strikes against U.S. and NATO targets, paired with co-orbital satellites tasked with maneuvering towards a then defunct Soviet satellite to pass close by the target satellite. The Soviets, according to Siddiqi, intended to destroy the target satellite with the co-orbiting chase satellite, but the fusing mechanism failed as it passed by. Moscow also used its space-based assets to test an anti-ballistic missile interceptor.[28] It was only after this large-scale test, where Moscow validated a proof of concept, that the Soviet leadership then chose to embark on an international campaign to limit the weaponization of space. In keeping with historical precedent, in 2022, Russia followed through and tested an updated anti-satellite missile, the Nudol, and destroyed a satellite in orbit.

China also has reportedly developed similar capabilities to maneuver in orbit to get close to U.S. satellites. Beijing has also sanctioned a considerable increase in deployed nuclear weapons. In 2024, the Department of Defense estimated that China had plans to deploy 1,000 nuclear weapons in 2030.[30] The rapid increase would bring Beijing’s deployed arsenal approximately in line with the currently deployed warheads in the United States and Russia.

In October 2021, The Financial Times reported that China had tested in August a hypersonic weapons system that circled the globe and dropped off a munition as the space plane glided back to earth and crashed.[31] This test is the latest iteration of the Soviet orbital bombardment system. Just as was the case previously, the advantage of this system is that China can quickly launch a nuclear weapon into orbit and have it travel in a way that limits warning time and gives planners options about novel routes to attack targets. The advantage of an orbital bombardment system is that the attacker can map current missile defenses and design a way to evade them. This is what China appears to be doing. It is using an older Soviet-era idea, most probably updated with a space plane of some sort, and testing ways to evade missile defense.

It also suggests a change in how Beijing views nuclear-era fighting. The increase in nuclear forces indicates that Chinese planners are re-considering contingency planning for how China would fight a nuclear-armed conflict with the United States, or at least deter such a conflict from ever taking place. This would seem to fit with the investments in space, deployment of ground based anti-satellite missiles, and expansion of nuclear strike options.

American dependence on space for all facets of warfighting, combined with the explosion in the number of satellites in orbit, has once again changed how adversaries think about conflict with the United States. In the past, it was feasible to assign small numbers of anti-satellite missiles that, with the evolution of precision, could be conventionally armed. Thus, an adversary could cost-effectively build up its interceptor magazines to hold at risk space-based assets. This is now no longer feasible. Hitting 7,000+ objects in a Starlink constellation requires building thousands of ground-based interceptors, which is not cost-efficient for the attacker. However, rather than simply accept defeat, adversaries have returned to an efficient way to think about destroying a large number of targets with a correspondingly small number of missiles: the brute force of nuclear weapons.

The Soviet Union understood at the outset of their co-orbital anti-satellite program that a nuclear weapon’s blast would be indiscriminate and kill every satellite in range. However, given the new asymmetry in the numbers of satellites in orbit (there is simply no realistic competitor to U.S. privately owned space companies), the cost-exchange ratio shifts for a potential attacker. The loss of U.S. capabilities with a strike would be so disproportionally large when compared to the loss of other nations that the debate about holding these satellites at risk with nuclear weapons becomes more salient. It also raises interesting questions about how best to defend against this new dynamic. In the past, the United States was at a disadvantage because its satellites would be risked should it target other nation’s satellites – it had much more to lose in a conflict in space than an adversary because it had more satellites and relied more heavily on them.

If Russia pushes forward again with a nuclear armed co-orbital system, the cost of deploying such a satellite is higher than the cost of launching a Starlink-like satellite. Thus, does it now make more sense for U.S. planners to dedicate forces to striking what is certain to be a small constellation of nuclear-armed satellites? The cost exchange may, in fact, come to favor the United States, the defense justified because of the need to protect U.S. orbiting platforms, and the resilience of any future satellite architecture may be considerable given the evolution of SpaceX’s launchers. Such a change will have an impact on nuclear stability and is worthy of further examination.

It is also important for the United States to consider assigning an anti-satellite role to the SM-3 and SM-6 missiles and to increase future purchases to allow for a portion of all future weapon buys to have a dual-deployment role. The United States should assume that any deployment of a Russian or Chinese nuclear-armed, co-orbital satellite will be small. Thus, dedicating a small amount of the total SM-3/6 buy to holding these weapons at risk would be beneficial to the United States. It would also be cost effective and allow for already fielded capabilities to be used to hold adversary assets at risk in space.

The economics of vertical launch should spur considerable work on how to decrease the cost of any proposed kill vehicle for a space-based missile defense. The cost of a large satellite constellation is no longer the barrier to missile defense deployment – instead, it is the cost of the kill vehicle. Working hard towards driving the purchase cost of any such system to a reasonable number would unlock the promise of SDI and Golden Dome and add yet more complexity to Russian and Chinese efforts to “out build” potential missile defense deployments. As part of this approach, the United States may need to consider how to more rapidly design, build, and launch early warning sensors. The idea would be to be able to get off the ground capabilities to augment the current U.S. sensor infrastructure. Such an approach could also give more capabilities for monitoring novel attack profiles, specifically the longer way around the earth to attack U.S. targets from the south.

It is important to think through how Russia and China would respond to any deployment of more capable U.S. missile defenses in space. The first and most obvious way to respond is to build up more nuclear forces. This is why continued engagement on arms control, per the thinking that guided the second offset, is worth undertaking. It would be wise to try and negotiate a trilateral cap on deployed strategic forces, perhaps at the 1,000-warhead mark. This would complicate Russian and Chinese targeting challenges, at a time when U.S. advantages in access to space remain considerable.

China and Russia may also consider developing short burn-time missiles to decrease the amount of time that their forces are in boost phase. This would negate some advantages to a space-based missile defense system and allow for attacking forces to get into mid-course flight more quickly, which is when they can launch countermeasures and decoys. This is yet another reason to consider further improvements to U.S. sensor architecture to increase warning time from launch to detection.

The United States could also update its nuclear doctrine. A nuclear blast in space, targeting U.S.-built products used for U.S. military purposes and in support of U.S. military operations, should be considered a nuclear attack on U.S. forces. This would allow for the United States to hold a reciprocal target at risk to a retaliatory strike, which could help deter an attacking leader from using a nuclear weapon in space.

Finally, the U.S. government should consider becoming the “insurer of last resort” for these companies. The new space industry is worth about $600 billion today, with projections for it to grow to more than $1 trillion in the 2030s. The increasing military contestation described in this paper puts commercial and civil constellations at great risk. This risk is only poorly appreciated by the new space industry, which for the most part is not insured against acts of war. The issue of orbital debris created from military tests is more ambiguous. Insurance companies are beginning to review their coverage and consider what sorts of products are appropriate for an increasingly contested environment. These changes will have a major impact on new space companies. It is in the government’s interest to ensure that innovation does not slow down. One way to do so is to provide further incentives through the provision of insurance, if indeed it does become a hindrance to future space flight.

The rapid changes in space have spurred American adversaries to return to concepts and ideas first tested and deployed during the Cold War. The United States should consider carefully how it plans to compete in space. The economics of space launch has placed the United States in an advantageous position to win this new space race.

[1] Asif Siddiqi, “Soviet Space Power During the Cold War,” in Harnessing the Heavens: National Defense Through Space, eds. Paul G. Gillespie and Grant T. Weller (United States Air Force Academy, 2008), 135-150.

[2] John D. Maurer, “The Forgotten Side of Arms Control: Enhancing U.S. Competitive Advantage, Offsetting Enemy Strength,” War on the Rocks, June 27, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/the-forgotten-side-of-arms-control-enhancing-u-s-competitive-advantage-offsetting-enemy-strengths/.

[3] Asif Siddiqi, “Soviet Space Power During the Cold War.”

[4] “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies,” United Nations, October 1967, https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html.

[5] Asif Siddiqi, “The Soviet Fractional Orbiting Bombardment System (FOBS): A Short Technical History,” Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly, no. 4 (Spring 2000): 22-32.

[6] “Russia Building Space A-Missile, McNamara says,” CIA Reading Room, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP70B00338R000300110028-3.pdf.

[7] Gregory W. Pedlow and Donald E. Welzenbach, The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance (Skyhorse Publishing, 2016).

[8] Asif A. Siddiqi, “The Soviet Co-Orbital Anti-Satellite System: A Synopsis,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 50, no. 6 (1997): 225-240, https://www.asifsiddiqi.com/s/Siddiqi-Soviet-Co-Orbital-Anti-Satellite-System-1997-1.pdf.

[9] Robert “Tony” Vincent, “Getting Serious About the Threat of High Altitude Nuclear Detonations,” War on the Rocks, September 23, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/09/getting-serious-about-the-threat-of-high-altitude-nuclear-detonations/.

[10] Robert “Tony” Vincent, “Getting Serious About the Threat of High Altitude Nuclear Detonations.”

[11] Dwayne A. Day and Robert Kennedy, “Barbarian in space: the secret space-laser battle station of the Cold War,” The Space Review, June 5, 2023, https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4598/1.

[12] “Report of the American Physical Society Study Group on Boost-Phase Intercept Systems for National Missile Defense: Scientific and Technical Issues,” American Physical Society, October 5, 2004, https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/71781/Barton-2004-Report%20of%20the%20American%20physical%20society%20study%20group.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[13] Rose E. Gottemoeller, “Conflict and Consensus in the Soviet Armed Forces,” RAND, 1989, https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R3759.html.

[14] Richard Whittle, Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2020).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Peter Mattis, “China’s ‘Three Warfares’ in Perspective,” War on the Rocks, January 30, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/01/chinas-three-warfares-perspective/.

[17] Steve Coll, The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the C.I.A. and the Origins of America’s Invasion of Iraq (Penguin Press, 2024).

[18] Jeffrey Lewis and Aaron Stein, “Who is Deterring Whom? The Place of Nuclear Weapons in Modern War,” War on the Rocks, June 16, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/06/who-is-deterring-whom-the-place-of-nuclear-weapons-in-modern-war/.

[19] Shirley Kan, “China’s Anti-Satellite Test,” Congressional Research Service, April 23, 2007, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA468025.pdf.

[20] Shirley Kan, “China’s Anti-Satellite Test.”

[21] Nuclear Posture Review Report, U.S. Congress, January 8, 2002, https://uploads.fas.org/media/Excerpts-of-Classified-Nuclear-Posture-Review.pdf.

[22] “Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy,” President of Russia, February 7, 2007, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034.

[23] Michael Kofman, “Russian Performance in the Russo-Georgian War Revisited,” War on the Rocks, September 4, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/09/russian-performance-in-the-russo-georgian-war-revisited/.

[24] “Russia announces major arms buildup,” CNN, March 17, 2009, https://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/03/17/russia.rearmament/index.html.

[25] Kenneth Chang, “Blue Origin Launches Bezos’s Space Dreams and Lands a Rocket,” New York Times, November 24, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/25/science/space/blue-origins-rocket-launches-and-lands.html;

[26] James Pethokoukis, “Moore’s Law Meet Musk’s Law: The Underappreciated Story of SpaceX and the Stunning Decline in Launch Costs,” American Enterprise Institute, March 7, 2025, https://www.aei.org/articles/moores-law-meet-musks-law-the-underappreciated-story-of-spacex-and-the-stunning-decline-in-launch-costs/.

[27] Chelsea Gohd, “2 Russian satellites are stalking a US spysat in orbit,” Space, February 11, 2020, https://www.space.com/russian-spacecraft-stalking-us-spy-satellite-space-force.html

[28] Siddiqi, “The Soviet Co-Orbital Anti-Satellite System: A Synopsis,” 235.

[29] Chelsea Gohd, “Russian anti-satellite missile test was the first of its kind,” Space, August 10, 2022, https://www.space.com/russia-anti-satellite-missile-test-first-of-its-kind

[30] “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” Department of Defense, 2024, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Dec/18/2003615520/-1/-1/0/MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2024.PDF.

[31] Demetri Sevastopulo and Kathrin Hille, “China tests new space capability with hypersonic missile,” Financial Times, October 16, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/ba0a3cde-719b-4040-93cb-a486e1f843fb.

FacebookTwitterEmailFlipboardMastodonLinkedInShare

Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

Founded in 1955, FPRI (http://www.fpri.org/) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests and seeks to add perspective to events by fitting them into the larger historical and cultural context of international politics.

NASA-ISRO Satellite Sends First Radar Images Of Earth’s Surface

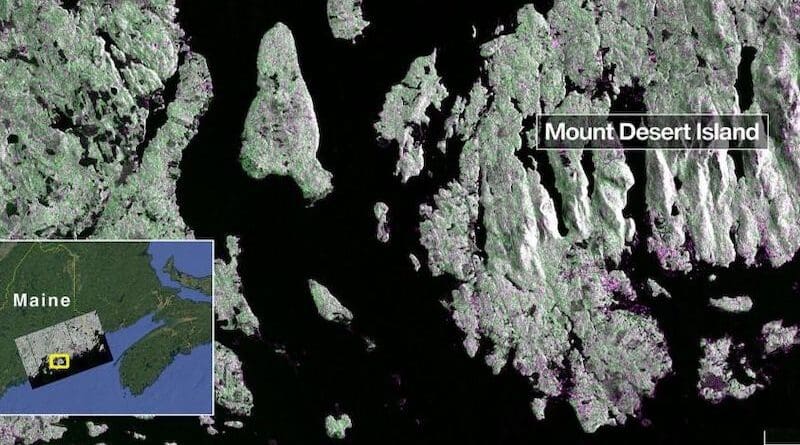

Captured on Aug. 21, this image from NISAR’s L-band radar shows Maine’s Mount Desert Island. Green indicates forest; magenta represents hard or regular surfaces, like bare ground and buildings. The magenta area on the island’s northeast end is the town of Bar Harbor. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The NISAR (NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar) Earth-observing radar satellite’s first images of our planet’s surface are in, and they offer a glimpse of things to come as the joint mission between NASA and ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation) approaches full science operations later this year.

“Launched under President Trump in conjunction with India, NISAR’s first images are a testament to what can be achieved when we unite around a shared vision of innovation and discovery,” said acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy. “This is only the beginning. NASA will continue to build upon the incredible scientific advancements of the past and present as we pursue our goal to maintain our nation’s space dominance through Gold Standard Science.”

Images from the spacecraft, which was launched by ISRO on July 30, display the level of detail with which NISAR scans Earth to provide unique, actionable information to decision-makers in a diverse range of areas, including disaster response, infrastructure monitoring, and agricultural management.

“By understanding how our home planet works, we can produce models and analysis of how other planets in our solar system and beyond work as we prepare to send humanity on an epic journey back to the Moon and onward to Mars,” said NASA Associate Administrator Amit Kshatriya. “The successful capture of these first images from NISAR is a remarkable example of how partnership and collaboration between two nations, on opposite sides of the world, can achieve great things together for the benefit of all.”

On Aug. 21, the satellite’s L-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) system, which was provided by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, captured Mount Desert Island on the Maine coast. Dark areas represent water, while green areas are forest, and magenta areas are hard or regular surfaces, such as bare ground and buildings. The L-band radar system can resolve objects as small as 15 feet (5 meters), enabling the image to display narrow waterways cutting across the island, as well as the islets dotting the waters around it.

Then, on Aug. 23, the L-band SAR captured data of a portion of northeastern North Dakota straddling Grand Forks and Walsh counties. The image shows forests and wetlands on the banks of the Forest River passing through the center of the frame from west to east and farmland to the north and south. The dark agricultural plots show fallow fields, while the lighter colors represent the presence of pasture or crops, such as soybean and corn. Circular patterns indicate the use of center-pivot irrigation.

The images demonstrate how the L-band SAR can discern what type of land cover — low-lying vegetation, trees, and human structures — is present in each area. This capability is vital both for monitoring the gain and loss of forest and wetland ecosystems, as well as for tracking the progress of crops through growing seasons around the world.

“These initial images are just a preview of the hard-hitting science that NISAR will produce — data and insights that will enable scientists to study Earth’s changing land and ice surfaces in unprecedented detail while equipping decision-makers to respond to natural disasters and other challenges,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “They are also a testament to the years of hard work of hundreds of scientists and engineers from both sides of the world to build an observatory with the most advanced radar system ever launched by NASA and ISRO.”

The L-band system uses a 10-inch (25-centimeter) wavelength that enables its signal to penetrate forest canopies and measure soil moisture and motion of ice surfaces and land down to fractions of an inch, which is a key measurement in understanding how the land surface moves before, during, and after earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and landslides.

The preliminary L-band images are an example of what the mission team will be able to produce when the science phase begins in November. The satellite was raised into its operational 464-mile (747-kilometer) orbit in mid-September.

The NISAR mission also includes an S-band radar, provided by ISRO’s Space Applications Centre, that uses a 4-inch (10-centimeter) microwave signal that is more sensitive to small vegetation, making it effective at monitoring certain types of agriculture and grassland ecosystems.

The spacecraft is the first to carry both L- and S-band radars. The satellite will monitor Earth’s land and ice surfaces twice every 12 days, collecting data using the spacecraft’s drum-shaped antenna reflector, which measures 39 feet (12 meters) wide — the largest NASA has ever sent into space.

The NISAR mission is a partnership between NASA and ISRO spanning years of technical and programmatic collaboration. The successful launch and deployment of NISAR builds on a strong heritage of cooperation between the United States and India in space.

The Space Applications Centre provided the mission’s S-band SAR. The U R Rao Satellite Centre provided the spacecraft bus. The launch vehicle was provided by Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, and launch services were through Satish Dhawan Space Centre. Key operations, including boom and radar antenna reflector deployment, are now being executed and monitored by the ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network’s global system of ground stations.

Tumbleweed rover tests demonstrate transformative technology for low-cost Mars exploration

Europlanet

image:

Team Tumbleweed with scaled prototype rovers at the wind tunnel at Aarhus.

view moreCredit: Team Tumbleweed.

A swarm of spherical rovers, blown by the wind like tumbleweeds, could enable large-scale and low-cost exploration of the martian surface, according to results presented at the Joint Meeting of the Europlanet Science Congress and the Division for Planetary Sciences (EPSC-DPS) 2025.

Recent experiments in a state-of-the-art wind tunnel and field tests in a quarry demonstrate that the rovers could be set in motion and navigate over various terrains in conditions analogous to those found on Mars.

Tumbleweed rovers are lightweight, 5-metre-diameter spherical robots designed to harness the power of martian winds for mobility. Swarms of the rovers could spread across the Red Planet, autonomously gathering environmental data and providing an unprecedented, simultaneous view of atmospheric and surface processes from different locations on Mars. A final, stationary phase would involve collapsing the rovers into permanent measurement stations dotted around the surface of Mars, providing long-term scientific measurements and potential infrastructure for future missions.

“Recent wind-tunnel and field campaigns have been a turning point in the Tumbleweed rover’s development,” said James Kingsnorth, Head of Science at Team Tumbleweed, who presented the results at EPSC-DPS2025 in Helsinki. “We now have experimental validation that Tumbleweed rovers could indeed operate and collect scientific data on Mars.”

In July 2025, Team Tumbleweed conducted a week-long experimental campaign, supported by Europlanet, at Aarhus University’s Planetary Environment Facility. Using scaled prototypes with 30-, 40- and 50-centimetre diameters, the team carried out static and dynamic tests in a wind tunnel with a variety of wind speeds and ground surfaces under a low atmospheric pressure of 17 millibars.

Results showed that wind speeds of 9-10 metres per second were sufficient to set the rover in motion over a range of Mars-like terrains including smooth and rough surfaces, sand, pebbles and boulder fields. Onboard instruments successfully recorded data during tumbling and the rover’s behaviour matched fluid-dynamics modelling, validating simulations. The scale-model prototypes were able to climb up a slope of 11.5 degrees in the chamber – equivalent to approximately 30 degrees on Mars – demonstrating that the rover could traverse even unfavourable slopes.

“Experiments with the prototypes in the Aarhus Wind Tunnel have provided big insights into how Tumbleweed rovers would operate on Mars,” said Mário João Carvalho de Pinto Balsemão, Team Tumbleweed’s Mission Scientist, who led the experimental campaign. “The results are conservative, as the weights of the scaled prototypes used in the experiments are exaggerated compared to the real thing, so the threshold wind speeds for setting the rovers rolling could be even less.”

Near-surface winds on Mars are currently not well understood due to the relatively sparse data collection. While data from rovers and landers on the surface show average wind speeds are generally in single digits, wind-generated vibrations recorded by NASA’s Insight mission over more than two martian years, as well as measurements gathered during the flights of the Ingenuity helicopter, show that higher wind-speeds can occur near the surface quite frequently.

“Data from Insight suggests that in Mars’s northern hemisphere during summer, daytime wind speeds are characterised by a wide distribution and are positively skewed toward higher wind speeds of around 10 metres per second, and while the nights are calmer, speeds of more 10 metres per second can sometimes be reached,” said Balsemão. “The results from Aarhus support our modelling, which shows that an average Tumbleweed rover – following the daily shifts and day-night cycles of the wind – could travel about 422 kilometres over 100 martian sols, with an average overall speed of about 0.36 kilometres per hour. In favourable conditions, the maximum range could be as much as 2,800 kilometres.”

Back in April, a 2.7-metre-diameter rover prototype, the Tumbleweed Science Testbed, was deployed in field tests in an inactive quarry in Maastricht in the Netherlands. The rover’s modular payload bay carried a suite of off-the-shelf sensors including a camera, a magnetometer, an inertial measurement unit and a GPS. These experiments confirmed that the platform could successfully gather and process environmental data in real time while tumbling over natural terrain.

The organisation behind the rovers, Team Tumbleweed, is an interdisciplinary group of young, entrepreneurial scientists. With main branches in Vienna in Austria and Delft in the Netherlands, Team Tumbleweed brings together people from over 20 countries.

The next steps for the team will include integrating more sophisticated instruments into the Tumbleweed Science Testbed payload, including radiation sensors, soil probes and dust sensors, refining the rover’s dynamics models, and scaling up the platform to higher technology readiness levels (TRLs). A further field campaign will take place in the Atacama Desert, Chile, in November, during which at least two Science Testbed rovers will carry instruments supplied by researchers from external partner organisations and will test swarm coordination strategies in Mars-like environments.

Scaled prototype Tumbleweed Rover in the wind tunnel at Aarhus.

Field tests with the Tumbleweed Science Testbed in a quarry in Maastricht in April 2025.

Field tests with the Tumbleweed Science Testbed in a quarry in Maastricht in April 2025.

Field tests with the Tumbleweed Science Testbed in a quarry in Maastricht in April 2025.

Credit

Team Tumbleweed/Sas Schilten

High Orbit, High Stakes: Germany’s Geopolitical Gamble In Space – Analysis

European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt near Frankfurt. Photo Credit: European Space Agency, Wikipedia Commons

By Scott N. Romaniuk and László Csicsmann

In February 2022, engineers across northern Germany stared in disbelief as thousands of wind turbines went dark—not from mechanical failure, but a cyberattack on the KA-SAT satellite network known as AcidRain. The hack disabled remote control for nearly 5,800 ENERCON turbines across Germany and Central Europe, cutting over 10 gigawatts of power. Wind generation had hit a record high that month, averaging more than 30,000 megawatts and sharply reducing reliance on coal and gas.

The disruption extended beyond Germany: in France, nearly 9,000 satellite internet customers lost connectivity, and about a third of subscribers across several European countries—including Germany, France, Hungary, Greece, Italy, and Poland—were affected. What initially appeared to be a technical glitch in green energy was, in fact, a stark warning shot from orbit, occurring nearly simultaneously with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

A Bold Policy Shift

Three years later, Berlin has answered. In a dramatic move, Germany pledged €35 billion (US$41 billion) to military space defense over the next decade—the largest commitment of its kind in the country’s history. The investment signals that space is no longer a peripheral concern but a frontline of national security, NATO defense, and Europe’s strategic autonomy.

German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius has sounded the alarm on the vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure in space. Speaking at a Berlin space conference, he stressed that Germany must defend itself in orbit just as fiercely as it does on land, sea, and air. Pistorius warned that Russia and China have rapidly expanded their space warfare capabilities: they can disrupt satellite operations, blind satellites, manipulate them, or even destroy them kinetically. The German military has already felt the sting of jamming attacks—proof that space is no longer a safe frontier.

A Shock from Orbit

The ViaSat hack was a watershed moment. For the first time, millions of Germans saw that satellite vulnerabilities were not abstract—they could ripple into daily life, turning off turbines, disrupting internet access, and threatening energy security. In a country heavily invested in renewable energy and digital infrastructure, the attack served as a jarring reminder that a hostile act in orbit can instantly cascade into terrestrial disruption.

For Berlin, it marked the end of strategic complacency. Space could no longer be treated as a benign or secondary theater. The scale of the funding—€35 billion—represents an unprecedented investment in a single capability domain, rivaled only by broader defense spending increases since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is not merely about buying satellites; it is a recognition that in 21st-century warfare, the frontlines now extend 36,000 kilometres above Earth.

Building Autonomous Capabilities

The German plan is ambitious and comprehensive, including:

- Resilient satellite systems designed to withstand jamming, hacking, and kinetic threats.

- Advanced orbital surveillance networks to detect and track hostile maneuvers or debris.

- A dedicated military satellite operations centre, the first of its kind in Germany, under the Bundeswehr’s Space Command, integrated into the Air Force since 2021.

Berlin’s shift goes beyond passive systems. The program may extend into launch capabilities—ensuring Germany can deploy its own assets—and potentially into offensive tools designed to deter adversaries. Such a move would have been unthinkable only a decade ago.

Pistorius has made the rationale clear: repeated instances of Russian reconnaissance satellites shadowing German military communications satellites—proximity operations that could tip into aggression—justify the potential for offensive deterrence. Germany intends to defend its assets with more than words.

Strengthening NATO and EU Security

For NATO, Germany’s move could reshape space defense. Independent German assets provide redundancy in communications and reconnaissance if US systems are degraded, spreading risk across the alliance. Stronger German space capabilities allow NATO to integrate space with cyber, land, sea, and air operations more effectively.

Berlin’s commitment resonates across the EU. Space is increasingly seen not just as a defense asset but as a pillar of resilience. Navigation, communications, banking, and even agriculture depend on satellites. By taking the lead, Germany embeds space into the EU’s drive for strategic autonomy. Shared frameworks—from satellite defense to ensuring the continuity of Galileo, the EU’s GNSS operational since December 2016—stand to benefit directly.

The symbolism matters too. Europe has often struggled to translate economic weight into military clout. Germany’s move demonstrates leadership, signaling to allies and rivals alike that Europe will not remain a junior partner in space.

Legal and Normative Context

Germany’s pivot raises questions in international law. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty bans WMDs in orbit but is silent on conventional weapons or electronic warfare. By exploring offensive deterrence, Berlin enters a grey zone.

Supporters argue Germany is responding to an already dangerous reality: Russia has tested anti-satellite missiles, China has conducted kinetic strikes on its own satellites, and the U.S. has created a Space Force. Critics warn that Berlin risks accelerating the erosion of norms that once sought to keep space peaceful.

Either way, Germany is now a rule-shaper. Its choices will influence EU and NATO debates on arms control, responsible conduct, and crisis management in orbit, and may even help shape new international codes of conduct for space security.

Industrial and Economic Dimension

Germany’s aerospace and defense industries stand to gain. Airbus Defence & Space and OHB SE are likely frontrunners for contracts, while smaller firms in software, sensors, cybersecurity, and AI-guided satellite systems will grow alongside them.

Military-driven innovations—hardened encryption, autonomous navigation, advanced debris-tracking, resilient satellite power grids—often spin off into civilian markets, strengthening telecommunications, logistics, and climate monitoring. The €35 billion investment is thus as much strategic industrial policy as military spending, helping Europe compete with the U.S. and China in the global aerospace race.

Public Opinion and Political Debate

Domestically, the announcement has divided opinion. Germany’s post-war culture has long been wary of militarization, especially in new domains. Opposition parties question the wisdom of spending billions on orbital weapons amid economic pressures.

Yet geopolitical developments—Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s assertive behavior in Asia—have shifted sentiment. Polls suggest growing acceptance that defense spending is necessary to protect infrastructure and deter coercion. In March 2025, Germany’s Bundestag approved a €500 billion defense and infrastructure package to counter ‘Putin’s war of aggression’, loosening constitutional debt limits. Passed with broad bipartisan support, the measure signals a growing consensus on strengthening national security.

Alliance Politics: Cooperation and Rivalry

Germany’s initiative reshapes alliance politics. France, with its advanced space program, may see Berlin as both collaborator and competitor. The U.S. has long urged allies to step up in high-tech domains. By taking responsibility, Germany contributes to collective deterrence, strengthens NATO cohesion, and underscores the strategic importance of emerging domains.

The Risk of Escalation

The real fear is escalation. Developing offensive space capabilities risks a classic security dilemma, where defensive measures can be seen as threatening. Moscow and Beijing could respond, fueling a spiral of competition. Even minor incidents—misinterpreted satellite maneuvers—could ignite crises.

Pistorius has stressed that Russian and Chinese activities pose tangible threats. Neutrality in space is no longer viable; Germany must build offensive capabilities to deter rivals rather than embolden them through restraint.

Entering the Military Space Race

Germany’s announcement places Europe in the modern space race, where dominance, survivability, and deterrence matter. Russia and China already field anti-satellite weapons; the U.S. has a Space Force. Germany signals it will not be left behind, potentially spurring other EU states to accelerate programs and laying groundwork for a collective European approach to space defense.

Long-Term Strategic Vision

Germany’s investment is more than satellites. It embeds space into an integrated defense ecosystem combining cyber, AI, and autonomous systems with traditional assets. Analysts see early building blocks of an EU Space Defence Doctrine—a framework that could make Europe a key player in orbital security by the 2030s.

A New Era in European Space Strategy

Germany’s billion-euro orbit gamble represents a fundamental recalibration of security thinking, placing orbit alongside land, sea, and air as a core domain of conflict and deterrence. The benefits are clear: strengthened NATO resilience, enhanced EU autonomy, industrial growth, and a louder German voice in shaping global norms. The risks are equally stark: escalation, domestic opposition, and the militarization of a domain once envisioned as peaceful.

Yet Berlin has concluded that the greater danger lies in inaction. By embracing space as a contested domain, Germany is not only defending its satellites—it is redefining Europe’s role in the next phase of global security. In doing so, it sends a clear signal: deterrence in space is essential, and shaping the rules of this emerging domain is as vital as protecting national territory. Germany’s move may set the template for European defense thinking for decades, balancing ambition, caution, and foresight in a rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape.

About the authors:

- Scott N. Romaniuk: Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Contemporary Asia Studies, Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies (CIAS), Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary

- László Csicsmann: Full Professor and Head of the Centre for Contemporary Asia Studies, Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies (CIAS), Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary; Senior Research Fellow, Hungarian Institute of International Affairs (HIIA)