Formed by Jack Poulson and other Silicon Valley dissidents, Tech Inquiry uncovers the tech industry’s role in weaponry and surveillance.

Jack Poulson, cofounder of Tech Inquiry

[Source images: Mark Sommerfeld; DeSa81/Pixabay]

Jack Poulson has developed an encyclopedic knowledge of how tech companies are evolving into military contractors. Tracking such intricate connections has become a full-time—though unpaid—job for the former Google research scientist as head of Tech Inquiry, a small nonprofit tackling the giant task of exposing ties between Silicon Valley and the U.S. military.

“Google, and tech companies in general, transitioning into weapons development is something that should be paid close attention to,” says Poulson. “And certainly employees of the company should have a voice in whether that work is performed.”

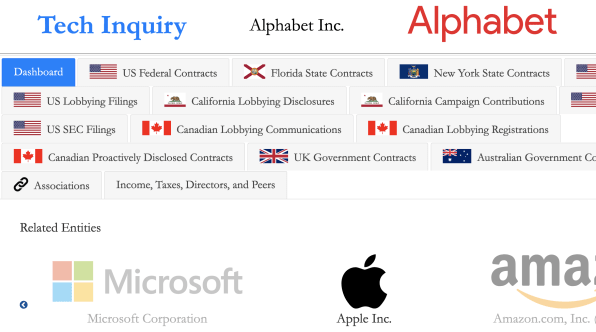

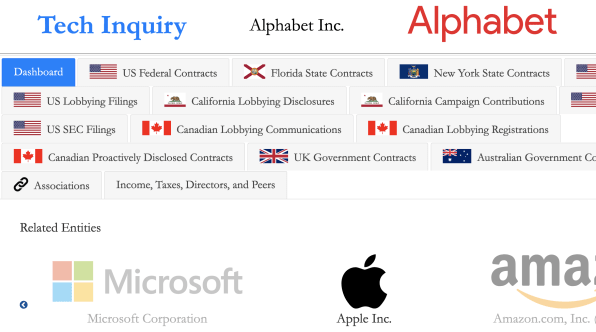

By delving through government contracting information and lobbying disclosures, and filing FOIA requests, Tech Inquiry has produced a set of custom databases for activists, journalists, and other researchers to probe tech-government connections. Its research covers the U.S. government as well as close intelligence allies, such as the U.K. and Canada. The group has also put out three dense reports that have been the foundation for many news articles. And it’s collaborating with advocacy groups to research the complex dealings and structures of tech firms.

Tech Inquiry’s latest report reveals (among many other things) Microsoft’s substantial role in a military drone AI program called Project Maven. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because the same program caused a huge rift at Google in 2018 when thousands of employees objected to the “Don’t be evil” company contributing AI tech to a killer drone program. Google ultimately left Maven, but its peers in tech continued on, with little public notice.

FROM TEAM PLAYER TO DISSIDENT

It was another Google controversy that gave Poulson international status. In 2018, when he was an AI researcher at the company, he encountered source code for Project Dragonfly, a version of Google’s namesake search engine being developed for mainland China. It contained a blacklist of forbidden queries, including the term “human rights.” Google’s facilitation of Chinese government censorship was well known within the company, but Poulson made news by taking a stand against it in a public resignation.

Poulson’s resignation letter quickly made him a spokesperson for tech worker opposition, with appeal to both the left and the right. “It was a reasonably bipartisan issue—actually, if anything, Republicans cared more about it than Democrats,” he says. “I wasn’t criticizing the United States. From my perspective, I was criticizing Google. But I’m sure from a lot of people’s perspectives, they were onboard because it included a critique of China.”

Poulson’s advocacy extended beyond censorship to also opposing Google’s work on military contracts, such as Maven. And he found himself invited to confidential meetings between tech CEOs and senior officials from the Department of Defense and intelligence agencies, who looked to him as the voice of techies opposed to working on weapons systems. “I’m not quite so sure I had any significant impact on what their opinions were,” he says. “But I certainly learned a lot about what sorts of relationships existed and who attended those sorts of meetings.”

Jack Poulson has developed an encyclopedic knowledge of how tech companies are evolving into military contractors. Tracking such intricate connections has become a full-time—though unpaid—job for the former Google research scientist as head of Tech Inquiry, a small nonprofit tackling the giant task of exposing ties between Silicon Valley and the U.S. military.

“Google, and tech companies in general, transitioning into weapons development is something that should be paid close attention to,” says Poulson. “And certainly employees of the company should have a voice in whether that work is performed.”

By delving through government contracting information and lobbying disclosures, and filing FOIA requests, Tech Inquiry has produced a set of custom databases for activists, journalists, and other researchers to probe tech-government connections. Its research covers the U.S. government as well as close intelligence allies, such as the U.K. and Canada. The group has also put out three dense reports that have been the foundation for many news articles. And it’s collaborating with advocacy groups to research the complex dealings and structures of tech firms.

Tech Inquiry’s latest report reveals (among many other things) Microsoft’s substantial role in a military drone AI program called Project Maven. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because the same program caused a huge rift at Google in 2018 when thousands of employees objected to the “Don’t be evil” company contributing AI tech to a killer drone program. Google ultimately left Maven, but its peers in tech continued on, with little public notice.

FROM TEAM PLAYER TO DISSIDENT

It was another Google controversy that gave Poulson international status. In 2018, when he was an AI researcher at the company, he encountered source code for Project Dragonfly, a version of Google’s namesake search engine being developed for mainland China. It contained a blacklist of forbidden queries, including the term “human rights.” Google’s facilitation of Chinese government censorship was well known within the company, but Poulson made news by taking a stand against it in a public resignation.

Poulson’s resignation letter quickly made him a spokesperson for tech worker opposition, with appeal to both the left and the right. “It was a reasonably bipartisan issue—actually, if anything, Republicans cared more about it than Democrats,” he says. “I wasn’t criticizing the United States. From my perspective, I was criticizing Google. But I’m sure from a lot of people’s perspectives, they were onboard because it included a critique of China.”

Poulson’s advocacy extended beyond censorship to also opposing Google’s work on military contracts, such as Maven. And he found himself invited to confidential meetings between tech CEOs and senior officials from the Department of Defense and intelligence agencies, who looked to him as the voice of techies opposed to working on weapons systems. “I’m not quite so sure I had any significant impact on what their opinions were,” he says. “But I certainly learned a lot about what sorts of relationships existed and who attended those sorts of meetings.”

Tech Inquiry’s Procurement and Lobbying Explorer allows anyone to probe the connections between companies and several national and state governments–with more to come.

Exposing those relationships became the goal of Tech Inquiry, which Poulson formed in summer 2019 along with four other tech experts. They include fellow Google dissidents Irene Knapp and Laura Nolan, anti-surveillance advocate Liz O’Sullivan, and tech consultant Shauna Gordon-McKeon. “Both Liz and Laura have played very significant roles in the campaign to stop killer robots,” says Poulson. Knapp is also a privacy advocate. And Gordon-McKeon develops open-source software to help groups govern themselves online.

Unsurprisingly given its founders’ backgrounds, the organization employs a fair amount of technology. Working at Google, Poulson specialized in natural language processing and recommendation systems. While we mostly encounter recommendation engines in features, such as Netflix suggestions and TikTok feeds, the tech goes much further. Tech Inquiry sets it loose on data, such as federal procurement records, to understand connections between companies and the government. It also analyzes language on company websites to find similarities between them.

The result is a recommendation system that guides research by Tech Inquiry or anyone who uses its tools. “Maybe they know about [data analysis firm] Palantir, but they don’t know about, say, a Black Cape or a Fivecast or one of those companies,” says Poulson. “Having a recommendation system helps fill in some of those similarities.”

But there’s still plenty of manual labor. Tech Inquiry’s previous report, Death and Taxes, documented how technology and defense companies benefited from the Trump corporate tax cuts and how much they have been able to avoid in federal taxes. The report, which covered 57 publicly traded companies, required reading through and collating over 1,000 financial filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Exposing those relationships became the goal of Tech Inquiry, which Poulson formed in summer 2019 along with four other tech experts. They include fellow Google dissidents Irene Knapp and Laura Nolan, anti-surveillance advocate Liz O’Sullivan, and tech consultant Shauna Gordon-McKeon. “Both Liz and Laura have played very significant roles in the campaign to stop killer robots,” says Poulson. Knapp is also a privacy advocate. And Gordon-McKeon develops open-source software to help groups govern themselves online.

Unsurprisingly given its founders’ backgrounds, the organization employs a fair amount of technology. Working at Google, Poulson specialized in natural language processing and recommendation systems. While we mostly encounter recommendation engines in features, such as Netflix suggestions and TikTok feeds, the tech goes much further. Tech Inquiry sets it loose on data, such as federal procurement records, to understand connections between companies and the government. It also analyzes language on company websites to find similarities between them.

The result is a recommendation system that guides research by Tech Inquiry or anyone who uses its tools. “Maybe they know about [data analysis firm] Palantir, but they don’t know about, say, a Black Cape or a Fivecast or one of those companies,” says Poulson. “Having a recommendation system helps fill in some of those similarities.”

But there’s still plenty of manual labor. Tech Inquiry’s previous report, Death and Taxes, documented how technology and defense companies benefited from the Trump corporate tax cuts and how much they have been able to avoid in federal taxes. The report, which covered 57 publicly traded companies, required reading through and collating over 1,000 financial filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

UNTANGLING THE CONNECTIONS

Tech Inquiry’s latest report, Easy as PAI, reveals complex defense and law-enforcement programs that use publicly available information (PAI), such as social media postings, satellite imagery, and location data. Some of these deals are revealed for the first time. Others, such as Project Maven, are fleshed out in greater detail.

One trend is how consumer technologies have migrated into military applications. For example, a company called SmileML made an iOS game in which people win points by mimicking the look of emojis. That produced data to train an AI in recognizing facial expressions—tech that smileML supplies to companies to assess the performance of their salespeople. SmileML also sold the tech for $235,000 to the Special Operations Command, which oversees special ops by four branches of the U.S. military, for projects involving “intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance,” per government documents.

Another case is X-Mode Social, which harvested location data from consumer mobile apps, such as a prayer app called Muslim Pro. The company later won a $200,000 contract to provide location data to the Defense Intelligence Agency, the military intel wing of the Pentagon. (According to a report in Motherboard, it’s unclear what the military did with this data.)

Neither of these deals was publicized, nor was there a direct link between the Pentagon and the companies. Instead, SmileML was a subcontractor to a British defense firm called BAE Systems. And X-Mode Social, which later changed its name to Outlogic, contracted through a company called Systems & Technology Research.

I must confess that my eyes glazed over at times as I struggled through the obtuse structures and relationships detailed in Poulson’s report. The tech-military connections are dense, often involving little-known companies or subsidiaries, running through obscure middlemen, and linking to unfamiliar government agencies in order to fulfill vaguely described, acronym-laden objectives.

But Poulson enjoys the challenge of decrypting these corporate dealings. “If you’re interested in a company, of course you’re interested in who owns them and what’s under them,” he says. “Because if you don’t know those things, then you’re not actually knowing what that company is doing.”

Unraveling the Project Maven ball of yarn was one of the biggest components of Tech Inquiry’s new report. The issue gained prominence because of the Google connection, coming at a time when employee activism, on a number of issues at the company, was spiking. And when Google pulled out of Maven in 2019, the program faded from public view. But it continued under the radar, involving dozens of tech companies. “Press attention given to different companies is kind of wildly off the mark as to what their roles have been in military contracting,” says Poulson.

As usual, these ties were filtered through contractors: Booz Allen Hamilton (Edward Snowden’s former employer) and a tech provider called ECS Federal. The latter managed three contracts that involved 33 tech companies. Microsoft tops the list, receiving $31.6 million last year to supply AI for analyzing video and motion. Other name brands on the list include Amazon Web Services, IBM, and Peter Thiel’s Palantir. But the second-biggest contractor (receiving $25.2 million) was Clarifai, a boutique AI company that’s providing facial recognition tech to the Pentagon. (Unlike some companies, Clarifai has been very up front about its work with the military.)

CHALLENGING THE MEDIA

The press has been key to Poulson’s personal rise as a tech critic, as well as publicizing Tech Inquiry’s research. The New York Times, for instance, has covered Poulson’s Google advocacy, run an opinion piece he wrote, and quoted him in several articles, such as one about Intel and Nvidia’s ties to Chinese government oppression.

But the Times now finds itself under Tech Inquiry’s microscope. Easy as PAI points out the paper’s collaboration with the nonprofit think tank Center for Advanced Defense Studies on an article about North Korean oil deliveries. That organization uses technology from controversial firm Palantir and has also contracted with the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency to provide what the records call “bulk datasets.” The think tank has also collaborated with Buzzfeed News, including on a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of detention centers in China’s Xinjiang region.

Tech Inquiry also publicizes the links between military contractors and media organizations ProPublica, MIT Technology Review, and The Washington Post. The three are partners in an association called The Center for New Data. The Center also includes two location-tracking data brokers: Outlogic, which harvested data from the Muslim prayer app; and Veraset, a company with ties to Saudi intelligence.

In some cases, news outlets that expose the activities of data harvesting technologies are utilizing the same or similar technologies. “Why is it that journalists are off limits for pointing out their usage of surveillance technology?” says Poulson.

GOING GLOBAL

Critical as he may be, Poulson recognizes the media as a key constituency for Tech Inquiry’s research tool. “I definitely know there are journalists that use it,” he says.

The group also aims to serve advocacy organizations. Recently, it helped the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE) with a project called Big Tech Sells War. Opposed to the military and surveillance projects of the 20-year “War on Terror,” ACRE built a website to document the tech industry’s role in that war. It draws heavily on data collected by Tech Inquiry.

Poulson’s group is currently working on a project to map the global footprint of cloud-computing companies. That’s a paid gig for worker union UNI Global, funded by the German government’s Friedrich Ebert Foundation, and it will bring some much-needed income. Tech Inquiry is very picky about where it gets funding, and doesn’t solicit or accept money from corporations or from foundations linked to tech billionaires, such as the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative or the Gates Foundation. Its most common funding is from individuals sending in $50 per month.

As a result, the organization has been an all-volunteer effort till now. Poulson says that it now has enough money to fund a part-time position, likely his. “That’s exciting to not just be burning cash,” he says, with a laugh. Not that he’s likely to limit his hours to those he’s paid for. “[This is] the only thing I’ve done for the past year,” he says.

And he intends to do a lot more. Tech Inquiry started out providing insight into companies’ dealings with national governments. Now it’s digging into state governments, with information on Florida and New York State procurement and California lobbying filings, for instance. Each state has its own system for making information available, which requires a lot of tweaking to automate data collection

The group is also going international. It already has data on the so-called “Five Eyes” intel alliance of the U.S., the U.K., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Now it’s setting sights on the European Union and China. It’s developing a machine-translation system to render these countries’ complex documents into English, which likely requires training their own AI models to handle the task.

As Tech Inquiry has evolved, it’s had to evaluate the identity it projects. On a personal level, its members favor restrictions on military technologies and on the role of Silicon Valley in developing them. But it wants to be seen as an objective source of data, available to anyone.

“We started out [with] advocacy. And so I don’t think you can ever really fully shake that as an organization,” says Poulson. But he’s trying to strike a neutral tone in his reporting, letting the information speak for itself without commentary. “I find more and more that if you find something that’s actually interesting, you don’t have to really infer anything from it,” he says. “You can just state the facts, and that’s enough.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sean Captain is a business, technology, and science journalist based in North Carolina. Follow him on Twitter @seancaptain.

No comments:

Post a Comment