Decentralisation can serve as deterrence to terrorism and violent extremism in a society.

Updated 2 days ago

There is a growing realisation even at the top leadership of the state that perhaps nothing else poses a bigger threat to the stability of Pakistan than violent extremism and terrorism. It has damaged the tolerant culture using self-proclaimed religious superiority by some to harm those who hold differing views or follow different faiths. Despite the fact that radicalism has been spreading widely in our society, we still have little understanding of what motivates people to engage in militancy. Who is more likely to join the extremist groups? Do financial hardships, victimisation, marginalisation, stress, or traumatic life events push individuals into extremist beliefs? How do militant groups succeed in attracting others to join their ranks? Can people change their minds and walk away from such violence-promoting elements? Can local communities engage residents in positive activities and counter polarising ideologies? All of these questions demand serious deliberation.

We try to explore whether a representative, autonomous local body system can reduce the risks of someone indulging in political violence, including terrorism. According to the existing research evidence for countries confronted with such threats, the answer is a resounding yes. Multiple channels appear to play a role. In contrast to central control, decentralisation empowers the representative local governments to exercise greater autonomy over their own affairs. It provides decision-making authority to the elected representatives, improves service delivery, addresses minority concerns, and prioritises fiscal allocations to more pressing needs. In essence, it serves as a catalyst to identify and address grievances and issues early on, before they spiral out of control. The built-in feedback mechanism through community engagement and inclusive governance facilitates peaceful resolutions of conflicts.

Before digging further into the topic at hand, it is worth noting that typically three methods are used for devolving authority to lower tiers of government. Deconcentration redistributes central power across many levels of government offices, ensuring that distinct bureaucracies are responsible for distinct tasks and duties. Delegation involves the transfer of powers, mainly administrative duties, to semi-autonomous public agencies or third parties like housing authorities, transportation and waste disposal services, to name a few. Decentralisation, however, constitutes a major devolution of administrative, fiscal, and legislative responsibilities to the representative bodies elected from and by the local constituents. The constituents can vote the elected bodies out of office if they feel unsatisfied with their performance. The fear of retribution fosters healthy competition among the competing candidates. Participatory governance can thereby promote work efficiency, reduce social divisions and promote mutual trust.

Let us take a relevant example to understand how local leadership through community participation may act as a vanguard in monitoring suspicious activities in their areas. The governments of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2014 and Punjab in 2015 enacted a law, requiring property owners and managers —whether a house, hotel, or hostel — to provide information about any new tenant to the local police station. The purpose of the law was to develop a database that could help with the investigation of any terrorist or criminal activities. Although the right step, its implementation faced several practical issues. First, hardly any awareness campaign was launched to raise public understanding of the law. Second, both the fear of falling into uninvited trouble and public distrust of the police, the property owners hesitated from reporting information about the renters. Third, already resource-crunched, it was impossible for the police to go door to door for seeking information about any tenants in the area. Therefore, in order to identify individuals who may embrace an extremist ideology or pose a threat of violence, it is important for the police to work with the local leadership under a formal legal framework.

The question now is why has a representative local body system failed to take roots in Pakistan. This is despite the fact that Article 140-A of the constitution clearly states that, "Each Province shall, by legislation, create a local government system and transfer political, administrative, and financial responsibility and power to the elected representatives of the local governments". Furthermore, the constitution mandates the Election Commission to hold local body elections, meaning that only elected representatives can form such a government. At times, we see the federal government running effective programmes to support provincial governments, such as battling the Covid-19 pandemic, disbursing funds through the Ehsaas programme, or combating aftermaths of any natural calamity with the help of the armed forces of Pakistan. While such efforts greatly help in dealing with large-scale crises, they cannot substitute for the service delivery matters or governance issues in districts, tehsils or union councils.

A detailed study by Cheema, Khwaja and Qadir (2006), titled, “Local government reforms in Pakistan: context, content and causes”, examines why the local body system has been ineffective. They argue that to understand the current state of decentralisation in Pakistan, one must first comprehend its historical context. The British established local governments in India not by building on the traditional panchayat system and empowering locals, but by setting up a powerful, nominated office of Deputy Commissioner (DC) in districts. This colonial legacy continued post-independence, where the military regimes had been proactive in enacting local government reforms, while political governments either undermined or ignored these reforms. Because of the weak local body system and centrally controlled DCs, the power focus shifted towards maximising parliamentary seats in the federal and provincial assemblies to form a government. Moreover, the rivalry between the provincial and local governments over constituency politics did not bode well for the implementation of the decentralisation programme. Therefore, controlling districts through nominated and pliable bureaucracy became politically expedient for the ruling elites, whether military or civilian.

Albeit, the "Devolution of Power" plan of General Pervaiz Musharraf, launched in January 2000 and implemented following a series of local government elections, is widely regarded as the most radical decentralisation reforms effort in Pakistan. It restructured the sub-provincial government significantly by delegating the administrative and expenditures responsibilities to the elected local bodies. The newly formed office of District Coordination Officer (DCO), formerly DC, now reported to the elected head of the local government. Furthermore, DCO also could no longer exercise the executive magistracy and revenue collection powers of the old DC system. While most public service delivery matters came under the purview of the local governments, their ability to raise revenue remained limited with a heavy dependence on funds on the discretion of the central or provincial governments. Clearly, as with any other system, a solid foundation of the local government system needed further structural changes in order to be truly independent and autonomous. Yet, this devolution plan made the local government system both effective and responsive to local needs. However, following the waning power of Musharraf after 2007, this system started to lose its ground. Unnecessary delays in the approval and disbursement of funds for projects planned by the local governments hindered their ability to serve the people at the grassroots level.

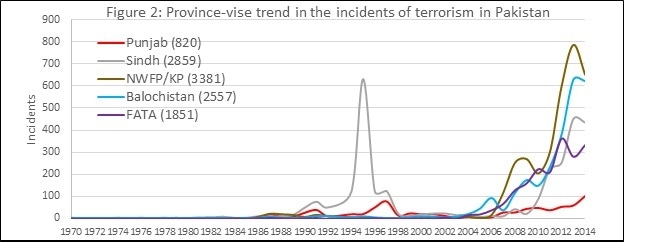

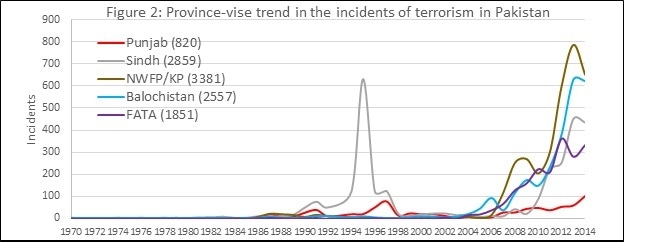

Nearly all data sources on terrorism show that after 1990 the incidents of both domestic and transnational terrorism were lowest during the period 2000-2007 in Pakistan. Figures 1 and 2 on the trends in number of overall terrorist incidents in Pakistan as well as in its provinces confirm this fact (data for these graphs come from the Global Terrorism Database). Despite its other flaws, this period is recognised as the best era for decentralisation in the country, where the local governments enjoyed substantial budgetary, administrative, and political control. While correlation does not imply causation, research evidence from a panel of countries supports the terrorism-mitigating effect of decentralisation.

Decentralisation can serve as deterrence to terrorism and violent extremism in a society. On one hand, communities acting as watchdogs make it more difficult for someone to engage in organised violence. On the other hand, alternative work opportunities, generated by improved governance and market incentives, yield greater financial rewards. The bottom line is that unless we make structural changes to the way we govern ourselves, we may just continue to stumble from one tragedy to another, whether caused by internal or external forces.

The Analytical Angle is a monthly column where top researchers bring rigorous evidence to policy debates in Pakistan. The series is a collaboration between the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan and Dawn.com. The views expressed are the authors’ alone.

Dr Javed Younas is a Professor of Economics at American University of Sharjah and a Research Fellow at Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan. Currently, he is spending his sabbatical leave for working on projects at Syracuse University and with the World Bank. His professional information can be found at https://sites.google.com/site/javedyounas

Dr Akbar Nasir Khan is a graduate of Harvard Kennedy School and he is currently working as DG NACTA Monitoring, Evaluation and Capacity Building. His earlier work includes National Internal Security Policy of Pakistan and Establishment of Punjab Safe Cities Authority in Punjab. He tweets at @akbarnasirkhan

There is a growing realisation even at the top leadership of the state that perhaps nothing else poses a bigger threat to the stability of Pakistan than violent extremism and terrorism. It has damaged the tolerant culture using self-proclaimed religious superiority by some to harm those who hold differing views or follow different faiths. Despite the fact that radicalism has been spreading widely in our society, we still have little understanding of what motivates people to engage in militancy. Who is more likely to join the extremist groups? Do financial hardships, victimisation, marginalisation, stress, or traumatic life events push individuals into extremist beliefs? How do militant groups succeed in attracting others to join their ranks? Can people change their minds and walk away from such violence-promoting elements? Can local communities engage residents in positive activities and counter polarising ideologies? All of these questions demand serious deliberation.

We try to explore whether a representative, autonomous local body system can reduce the risks of someone indulging in political violence, including terrorism. According to the existing research evidence for countries confronted with such threats, the answer is a resounding yes. Multiple channels appear to play a role. In contrast to central control, decentralisation empowers the representative local governments to exercise greater autonomy over their own affairs. It provides decision-making authority to the elected representatives, improves service delivery, addresses minority concerns, and prioritises fiscal allocations to more pressing needs. In essence, it serves as a catalyst to identify and address grievances and issues early on, before they spiral out of control. The built-in feedback mechanism through community engagement and inclusive governance facilitates peaceful resolutions of conflicts.

Before digging further into the topic at hand, it is worth noting that typically three methods are used for devolving authority to lower tiers of government. Deconcentration redistributes central power across many levels of government offices, ensuring that distinct bureaucracies are responsible for distinct tasks and duties. Delegation involves the transfer of powers, mainly administrative duties, to semi-autonomous public agencies or third parties like housing authorities, transportation and waste disposal services, to name a few. Decentralisation, however, constitutes a major devolution of administrative, fiscal, and legislative responsibilities to the representative bodies elected from and by the local constituents. The constituents can vote the elected bodies out of office if they feel unsatisfied with their performance. The fear of retribution fosters healthy competition among the competing candidates. Participatory governance can thereby promote work efficiency, reduce social divisions and promote mutual trust.

Let us take a relevant example to understand how local leadership through community participation may act as a vanguard in monitoring suspicious activities in their areas. The governments of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2014 and Punjab in 2015 enacted a law, requiring property owners and managers —whether a house, hotel, or hostel — to provide information about any new tenant to the local police station. The purpose of the law was to develop a database that could help with the investigation of any terrorist or criminal activities. Although the right step, its implementation faced several practical issues. First, hardly any awareness campaign was launched to raise public understanding of the law. Second, both the fear of falling into uninvited trouble and public distrust of the police, the property owners hesitated from reporting information about the renters. Third, already resource-crunched, it was impossible for the police to go door to door for seeking information about any tenants in the area. Therefore, in order to identify individuals who may embrace an extremist ideology or pose a threat of violence, it is important for the police to work with the local leadership under a formal legal framework.

The question now is why has a representative local body system failed to take roots in Pakistan. This is despite the fact that Article 140-A of the constitution clearly states that, "Each Province shall, by legislation, create a local government system and transfer political, administrative, and financial responsibility and power to the elected representatives of the local governments". Furthermore, the constitution mandates the Election Commission to hold local body elections, meaning that only elected representatives can form such a government. At times, we see the federal government running effective programmes to support provincial governments, such as battling the Covid-19 pandemic, disbursing funds through the Ehsaas programme, or combating aftermaths of any natural calamity with the help of the armed forces of Pakistan. While such efforts greatly help in dealing with large-scale crises, they cannot substitute for the service delivery matters or governance issues in districts, tehsils or union councils.

A detailed study by Cheema, Khwaja and Qadir (2006), titled, “Local government reforms in Pakistan: context, content and causes”, examines why the local body system has been ineffective. They argue that to understand the current state of decentralisation in Pakistan, one must first comprehend its historical context. The British established local governments in India not by building on the traditional panchayat system and empowering locals, but by setting up a powerful, nominated office of Deputy Commissioner (DC) in districts. This colonial legacy continued post-independence, where the military regimes had been proactive in enacting local government reforms, while political governments either undermined or ignored these reforms. Because of the weak local body system and centrally controlled DCs, the power focus shifted towards maximising parliamentary seats in the federal and provincial assemblies to form a government. Moreover, the rivalry between the provincial and local governments over constituency politics did not bode well for the implementation of the decentralisation programme. Therefore, controlling districts through nominated and pliable bureaucracy became politically expedient for the ruling elites, whether military or civilian.

Albeit, the "Devolution of Power" plan of General Pervaiz Musharraf, launched in January 2000 and implemented following a series of local government elections, is widely regarded as the most radical decentralisation reforms effort in Pakistan. It restructured the sub-provincial government significantly by delegating the administrative and expenditures responsibilities to the elected local bodies. The newly formed office of District Coordination Officer (DCO), formerly DC, now reported to the elected head of the local government. Furthermore, DCO also could no longer exercise the executive magistracy and revenue collection powers of the old DC system. While most public service delivery matters came under the purview of the local governments, their ability to raise revenue remained limited with a heavy dependence on funds on the discretion of the central or provincial governments. Clearly, as with any other system, a solid foundation of the local government system needed further structural changes in order to be truly independent and autonomous. Yet, this devolution plan made the local government system both effective and responsive to local needs. However, following the waning power of Musharraf after 2007, this system started to lose its ground. Unnecessary delays in the approval and disbursement of funds for projects planned by the local governments hindered their ability to serve the people at the grassroots level.

Nearly all data sources on terrorism show that after 1990 the incidents of both domestic and transnational terrorism were lowest during the period 2000-2007 in Pakistan. Figures 1 and 2 on the trends in number of overall terrorist incidents in Pakistan as well as in its provinces confirm this fact (data for these graphs come from the Global Terrorism Database). Despite its other flaws, this period is recognised as the best era for decentralisation in the country, where the local governments enjoyed substantial budgetary, administrative, and political control. While correlation does not imply causation, research evidence from a panel of countries supports the terrorism-mitigating effect of decentralisation.

Decentralisation can serve as deterrence to terrorism and violent extremism in a society. On one hand, communities acting as watchdogs make it more difficult for someone to engage in organised violence. On the other hand, alternative work opportunities, generated by improved governance and market incentives, yield greater financial rewards. The bottom line is that unless we make structural changes to the way we govern ourselves, we may just continue to stumble from one tragedy to another, whether caused by internal or external forces.

The Analytical Angle is a monthly column where top researchers bring rigorous evidence to policy debates in Pakistan. The series is a collaboration between the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan and Dawn.com. The views expressed are the authors’ alone.

Dr Javed Younas is a Professor of Economics at American University of Sharjah and a Research Fellow at Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan. Currently, he is spending his sabbatical leave for working on projects at Syracuse University and with the World Bank. His professional information can be found at https://sites.google.com/site/javedyounas

Dr Akbar Nasir Khan is a graduate of Harvard Kennedy School and he is currently working as DG NACTA Monitoring, Evaluation and Capacity Building. His earlier work includes National Internal Security Policy of Pakistan and Establishment of Punjab Safe Cities Authority in Punjab. He tweets at @akbarnasirkhan

No comments:

Post a Comment