JANUARY 9, 2022

ECONOMY

How Healthy Are US Public Pensions?

While news media coverage – and critics of public pensions – often draw attention to the large unrestricted liabilities, a new study Provides a new way of looking at those liabilities from a public-pension business group – the economy and market they say is more relevant to the SPXWork.

The group, the National Conference on Public Employees Retirement Systems (NCPERS), argues for a new approach to considering liabilities in the context of economic development, known as “sustainability assessment”.

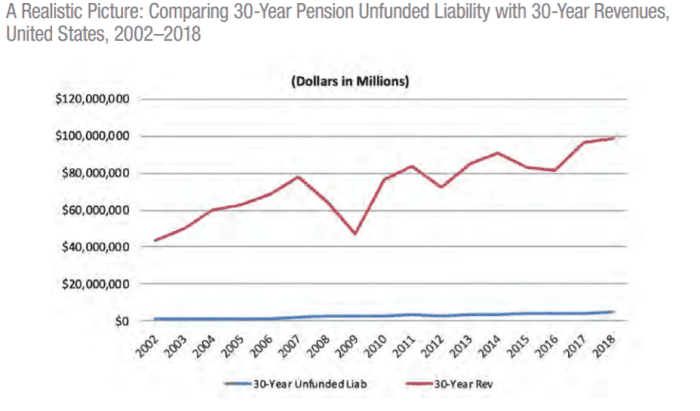

Critics of public pensions compare “30 years of pension liabilities, i.e. liabilities that are amortized in 30 years, with one year of state and local revenues. They then argue that public pensions are not sustainable,” says NCPER. The report’s author, Michael Kahn, writes.

“Comparing 30 years of pension liabilities to one year of state and local revenue is like a bank telling a borrower that his 30-year mortgage is due at the end of this year,” he said.

NCPERS argues that traditional methods of presenting pension liabilities are often misleading.

Instead, Kahn writes, outstanding public pension liabilities should be placed in the context of the 30-year period in which they are amortized, not considered something that must be paid immediately.

NCPERS argues that its approach to analyzing revenue and liabilities is more accurate.

Source: NCPRS

Kahn argues that such an approach should be an additional tool for monitoring how well-funded and sustainable a pension plan is, in addition to existing, familiar approaches such as actuarial analysis and stress testing.

It urges “to monitor stability on an ongoing basis and to make fiscal adjustments to keep the ratio between unfunded liabilities and economic capacity stable, on average, over the past two decades.”

As an example, he indicates a 2020 opinion piece From the Chicago Tribune, which claims that pension liabilities in Illinois total 10 times state and local revenues. “It certainly sounds terrible,” Kahn writes, “but it is a false comparison. When we compare pension liabilities amortized over 30 years with 30 years of revenue (an apples-to-apples comparison), then They account for only 8% of the revenue.

While it may be tempting to find a new and more compelling way to frame liabilities, the NCPERS report adds to a recent wave of public-pension research that argues there are good reasons to bring broader context to the issue of pension funding.

a 2021 Working Papers from the Brookings Institution Challenged the idea that state and local governments should fund pensions in full—that is, for the entire 30-year period as Kahn refers to above.

“Governments don’t have to pay off their debt like a house,” said Lewis Sheiner, one of the co-authors of the Brookings paper, in an interview with Businesshala. “They can just keep turning it around. They are never going out of business and they have to pay all at once.”

Public pensions don’t need to be fully funded to be sustainable, paper finds

To be sure, there are some public-pension schemes whose funding levels are not sustainable, and which must be addressed urgently. The Kentucky Employee Retirement System is one of the least funded systems in the nation, according to statistics from Retirement Research Center at Boston CollegeAs of 2019, only 16.5% was funded.

He runs the worst funded public pension in the country. Here’s the story of his ‘good news’

What’s more, any analysis of sustainability relies on governments making the necessary contributions to them in both good times and bad, something that hasn’t always happened.

But there are also solid reasons to criticize those details as severely framed as a push to fully fund pension conditions. Among them: dedicating a large portion of an operating budget to future expenses that can meet actual current needs, such as schools or capital projects.

In addition, the perceived need to fully fund 30-year liabilities may cause municipalities to engage in financial practices that are arguably more risky or harmful, such as taking out loans to plug the pension gap.

Read further: State and local governments have issued more pension bonds this year than ever before

Kahn argues that such an approach should be an additional tool for monitoring how well-funded and sustainable a pension plan is, in addition to existing, familiar approaches such as actuarial analysis and stress testing.

It urges “to monitor stability on an ongoing basis and to make fiscal adjustments to keep the ratio between unfunded liabilities and economic capacity stable, on average, over the past two decades.”

As an example, he indicates a 2020 opinion piece From the Chicago Tribune, which claims that pension liabilities in Illinois total 10 times state and local revenues. “It certainly sounds terrible,” Kahn writes, “but it is a false comparison. When we compare pension liabilities amortized over 30 years with 30 years of revenue (an apples-to-apples comparison), then They account for only 8% of the revenue.

While it may be tempting to find a new and more compelling way to frame liabilities, the NCPERS report adds to a recent wave of public-pension research that argues there are good reasons to bring broader context to the issue of pension funding.

a 2021 Working Papers from the Brookings Institution Challenged the idea that state and local governments should fund pensions in full—that is, for the entire 30-year period as Kahn refers to above.

“Governments don’t have to pay off their debt like a house,” said Lewis Sheiner, one of the co-authors of the Brookings paper, in an interview with Businesshala. “They can just keep turning it around. They are never going out of business and they have to pay all at once.”

Public pensions don’t need to be fully funded to be sustainable, paper finds

To be sure, there are some public-pension schemes whose funding levels are not sustainable, and which must be addressed urgently. The Kentucky Employee Retirement System is one of the least funded systems in the nation, according to statistics from Retirement Research Center at Boston CollegeAs of 2019, only 16.5% was funded.

He runs the worst funded public pension in the country. Here’s the story of his ‘good news’

What’s more, any analysis of sustainability relies on governments making the necessary contributions to them in both good times and bad, something that hasn’t always happened.

But there are also solid reasons to criticize those details as severely framed as a push to fully fund pension conditions. Among them: dedicating a large portion of an operating budget to future expenses that can meet actual current needs, such as schools or capital projects.

In addition, the perceived need to fully fund 30-year liabilities may cause municipalities to engage in financial practices that are arguably more risky or harmful, such as taking out loans to plug the pension gap.

Read further: State and local governments have issued more pension bonds this year than ever before

No comments:

Post a Comment