Published: May 30, 2022

Since the New York Times published its recent series of bombshell articles about the crippling reparations that France imposed on Haiti after it won independence in 1804, much has been written about how this 150 million franc “indemnity” had virtually doomed the fledgling country before it had a chance to establish itself. The New York Times pieces outlined the huge long-term impact of these enforced payments and demonstrate that they cost the Haitian economy billions of dollars in lost economic growth, affecting the island well into the 21st century.

Historians of Haiti have remarked that the New York Times’ core claims are hardly groundbreaking. The long-term effects of the debt on the Haitian economy have long been acknowledged, researched and taught. Nevertheless the newspaper’s detailed account, with its additional evidence and fresh calculations, has allowed the story to achieve the kind of public visibility most professional historians can only dream of. This is undoubtedly positive.

But this account, for all its moral force and political relevance, also reinforces a longstanding public perception of Haitian history as a story of unremitting failure. Of course this is justified in many ways. To this day, Haiti remains one of the poorest countries in the world, for which France (along with the United States and others) bears undeniable responsibility. But Haitian independence deserves to be remembered for more than its long, tragic aftermath. It was, in fact, a stunningly innovative event which dramatically changed the course of world history.

Freedom fighters

Before the Haitian revolution, Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was then known) was France’s largest and richest colony. Its population primarily consisted of enslaved black people, who lived and worked under a small elite of white plantation owners. When the French revolution broke out in 1789, it triggered a series of revolts and conflicts on the island. These involved white colonists, black enslaved people, free black and mixed-race people, as well as the French, British and Spanish states.

By 1804, the black and mixed-race insurgents had joined forces and claimed victory. White colonists were driven out or killed. On January 1 1804 a former slave, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, proclaimed the independence of the island in the name of the Haitian people.

It was a complex, lengthy, shockingly violent process. For a long time, it was treated as a bloody footnote in Atlantic history, and left out of the triumphant accounts that narrated “the age of democratic revolutions”. But it is now increasingly being viewed by historians as a major turning point in world history. There are several reasons for this.

Emancipation in the New World

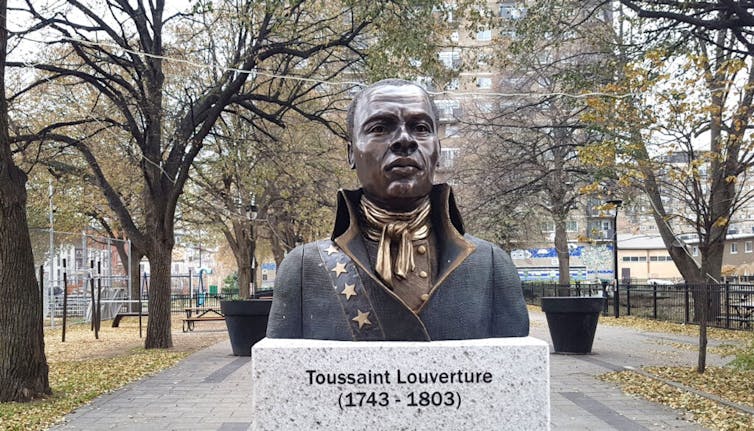

The first, and most immediately evident reason, relates to the history of colonial slavery. The Haitian revolution was a multifaceted conflict – but from 1791 its driving force was the great antislavery uprising spearheaded by the charismatic leader Toussaint Louverture. To this day it remains the only truly successful slave revolt in history.

It would be difficult to overstate the impact of the Haitian example on the history of emancipation in the New World. It raised the old spectre of slave rebellion and shocked slave owners across the Americas, but it also informed the British emancipation debate. In the 1810s the support Haiti provided to Simón Bolívar’s liberation movement played a major part in ending slavery in northern South America. Haitian emancipation also encouraged uprisings and rebellions in the US, Cuba and Barbados. It continued to inspire black people across the New World until the final abolition of slavery by Brazil in 1888.

The Haitian revolutionaries also durably transformed the international landscape. Emerging from an 18th-century world ruled by monarchies and colonial empires, Haiti became the first black republic in the world. It was only the second state to claim independence from a European empire, after the US.

Notably, it was the first to be ruled by formerly enslaved people. Independent Haiti was, in many ways, ahead of its time – it would take another century and a half for another significant decolonisation movement to emerge and finally topple the great European empires, in the second half of the 20th century.

Universal human rights

Amid all the tumult and upheavals of revolution, the Haitian people’s claim to independence was also philosophically groundbreaking. The Declaration of Independence of 1804 ended the Haitian revolution with a powerful assertion of national sovereignty:

We must, with one last act of national authority, forever assure the empire of liberty in the country of our birth … we must live independent or die.

By justifying independence in terms of the universal rights of mankind, Haitian leaders were deploying the same novel philosophical principles that underpinned the American and French revolutions. But, unlike the American and French republics, the new Haitian nation was to be rooted in its radical commitment to universal emancipation.

For all the above reasons, the Haitian revolution deserves to be remembered on its own terms – not only as the origin of a historical injustice, but also as one of the great revolutions of the Enlightenment, and a forerunner of modern decolonisation movements.

New York Times admits truth of Haitian coup

“A Haitian president demands reparations and ends up in exile”, declared the front-page of Wednesday’s New York Times. Eighteen years later those who opposed the US, French and Canadian coup have largely won the battle over the historical record.

French ambassador Thierry Burkard admits that President Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s call for the restitution of Haiti’s debt (ransom) of independence partly explains why he was ousted in 2004. Burkard told the Times the elected president’s removal was “a coup” that was “probably a bit about” Aristide’s campaign for France to repay Haiti.

Other major outlets have also investigated the coup recently. In 2020 Radio-Canada’s flagship news program “Enquête” interviewed Denis Paradis, the Liberal minister responsible for organizing the 2003 Ottawa Initiative on Haiti where US, French and Canadian officials discussed ousting the elected president and putting the country under UN trusteeship. Paradis admitted to Radio-Canada that no Haitian officials were invited to discuss their own country’s future and the imperial triumvirate broached whether “the principle of sovereignty is unassailable?” Enquête also interviewed long time Haitian Canadian activist and author Jean Saint-Vil who offered a critical perspective on the discussion to oust Aristide.

Radio-Canada and the Times’ coverage was influenced by hundreds of articles published by solidarity campaigners in left wing outlets. Damming the Flood: Haiti and the Politics of Containment: Repression and Resistance in Haiti, 2004–2006, Canada in Haiti: Waging War on the Poor Majority, Haiti’s New Dictatorship: The Coup, the Earthquake and the UN Occupation, An Unbroken Agony Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President provide richer documentation about the coup, as do documentaries Haiti: We Must Kill the Bandits, Haiti Betrayed and Aristide and the Endless Revolution.

The Times article on Aristide’s ouster was part of a series on imperialism in Haiti the paper published on its front page over four days. “The Ransom” detailed the cost to Haiti — calculated at between $21 billion and $115 billion — of paying France to recognize its independence. “A bank created for Haiti funneled wealth to France” showed how Crédit Industriel et Commercial further impoverished the nation in the late 1800s while “Invade Haiti, Wall Street urged, And American military obliged” covered the brutal 1915–34 US occupation, which greatly reshaped its economy to suit foreign capitalists.

The Times decision to spend tens, maybe hundreds, of thousands of dollars on the series was no doubt influenced by the Black Lives Matter movement and the paper’s 1619 project on slavery. Additionally, Saint-Vil and other Haitian-North American activists have been calling for France to repay the ransom for more than two decades. In 2010 a group of mostly Canadian activists published a fake announcement indicating that France would repay the debt. Tied to France’s Bastille Day and the devastating 2010 earthquake, the stunt by the Committee for the Reimbursement of the Indemnity Money Extorted from Haiti (CRIME) forced Paris to deny it, which the Times reported. The group also published a public letter that garnered significant international attention.

While these campaigns likely spurred the series, a number of academics made it about themselves. White Harvard professor Mary Lewis bemoaned that her research assistant was cited in “The Ransom” but she wasn’t. Another academic even apologized for sharing the important story. “I regret sharing the NYT article on Haiti yesterday. So many scholars are noting their egregious editorial practices. The writers of the article did not properly credit their sources.” Unfortunately, the academics’ tweets received thousands of likes.

Leaving aside the pettiness of academia, the series is not without questions and criticisms. First, will the Times apply the historical logic of the series to its future coverage of Haiti or continue acting as a stenographer for the State Department? More directly, why didn’t the series mention the “Core Group” that largely rules Haiti today? The series is supposed to show how foreign intervention has contributed to Haitian impoverishment and political dysfunction, but the Times ignores a direct line between the 2004 coup and foreign alliance that dominates the country today.

Last week Haitians protested in front of the Canadian embassy in Port-au-Prince. They chanted against the Core Group, which consists of representatives from the US, Canada, EU, OAS, UN, Spain, Brazil and France. A protester banged a rock on the gates. Previously, protesters have hurled rocks and molotov cocktails, as well as burned tires, in front of the Canadian Embassy.

The Times series has solidified the historical narrative regarding the 2004 coup and popularized the history of imperialism in Haiti. The series is a boon to North Americans campaigning for a radical shift in policy towards a country born of maybe the greatest victory ever for equality and human dignity.

But the point of activism is not simply to describe the world, but to change it.

No comments:

Post a Comment