The Conversation

August 5, 2023

NASA/Eyes on Asteroids

Asteroids are chunks of rock left over from the formation of our Solar System. Approximately half a billion asteroids with sizes greater than four meters in diameter orbit the Sun, traveling through our Solar System at speeds up to about 30 kilometres per second – about the same speed as Earth.

Asteroids are certainly good at capturing the public imagination. This follows many Hollywood movies imagining the destruction they could cause if a big one hits Earth.

Almost every week we see online headlines describing asteroids the size of a “bus”, “truck”, “vending machine”, “half the size of a giraffe”, or indeed a whole giraffe. We have also had headlines warning of “city killer”, “planet killer” and “God of Chaos” asteroids.

Of course, the threats asteroids pose are real. Famously, about 65 million years ago, life on Earth was brought to its knees by what was likely the impact of a big asteroid, killing off most dinosaurs. Even a four-meter object (half a giraffe, say) traveling at a relative speed of up to 60 kilometers per second is going to pack a punch.

But beyond the media labels, what are the risks, by the numbers? How many asteroids hit Earth and how many can we expect to zip past us?

What is the threat of a direct hit?

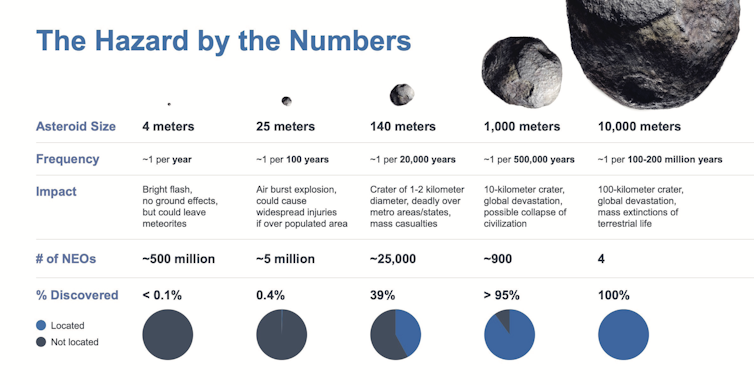

In terms of asteroids hitting Earth, and their impact, the graphic below from NASA summarizes the general risks.

ADVERTISEMENT

There are far more small asteroids than large asteroids, and small asteroids cause much less damage than large asteroids.

Asteroid statistics and the threats posed by asteroids of different sizes. NEOs are near-Earth objects, any small body in the Solar System whose orbit brings it close to our planet. NASA

So, Earth experiences frequent but low-impact collisions with small asteroids, and rare but high-impact collisions with big asteroids. In most cases, the smallest asteroids largely break up when they hit Earth’s atmosphere, and don’t even make it down to the surface.

When a small asteroid (or meteoroid, an object smaller than an asteroid) hits Earth’s atmosphere, it produces a spectacular “fireball” – a very long-lasting and bright version of a shooting star, or meteor. If any surviving bits of the object hit the ground, they are called meteorites. Most of the object burns up in the atmosphere.

How many asteroids fly right past Earth?

A very simplified calculation gives you a sense for how many asteroids you might expect to come close to our planet.

The numbers in the graphic above estimate how many asteroids could hit Earth every year. Now, let’s take the case of four-meter asteroids. Once per year, on average, a four-meter asteroid will intersect the surface of Earth.

If you doubled that surface area, you’d get two per year. Earth’s radius is 6,400km. A sphere with twice the surface area has a radius of 9,000km. So, approximately once per year, a four-meter asteroid will come within 2,600km of the surface of Earth – the difference between 9,000km and 6,400km.

Double the surface area again and you could expect two per year within 6,400km of Earth’s surface, and so on. This tallies pretty well with recent records of close approaches.

A few thousand kilometers is a pretty big distance for objects a handful of meters in size, but most of the asteroids covered in the media are passing at much, much larger distances.

Astronomers consider anything passing closer than the Moon – approximately 300,000km – to be a “close approach”. “Close” for an astronomer is not generally what a member of the public would call “close”.

In 2022 there were 126 close approaches, and in 2023 we’ve had 50 so far.

Now, consider really big asteroids, bigger than one kilometer in diameter. The same highly simplified logic as above can be applied. For every such impact that could threaten civilization, occurring once every half a million years or so, we could expect thousands of near misses (closer than the Moon) in the same period of time.

Such an event will occur in 2029, when asteroid 153814 (2001 WN5) will pass 248,700km from Earth.

How do we assess threats and what can we do about it?

Approximately 95% of asteroids of size greater than one kilometer are estimated to have already been discovered, and the skies are constantly being searched for the remaining 5%. When a new one is found, astronomers take extensive observations to assess any threat to Earth.

The Torino Scale categorizes predicted threats up to 100 years into the future, the scale being from 0 (no hazard) to 10 (certain collision with big object).

Currently, all known objects have a rating of zero. No known object to date has had a rating above 4 (a close encounter, meriting attention by astronomers).

So, rather than hearing about giraffes, vending machines, or trucks, what we really want to know from the media is the rating an asteroid has on the Torino Scale.

Finally, technology has advanced to the point we have a chance to do something if we ever do face a big number on the Torino Scale. Recently, the DART mission collided a spacecraft into an asteroid, changing its trajectory. In the future, it is plausible that such an action, with enough lead time, could help to protect Earth from collision.

Steven Tingay, John Curtin Distinguished Professor (Radio Astronomy), Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment