SPACE/COSMOS

Photos: Astronomers capture the birth of planets around a baby sun outside our solar system

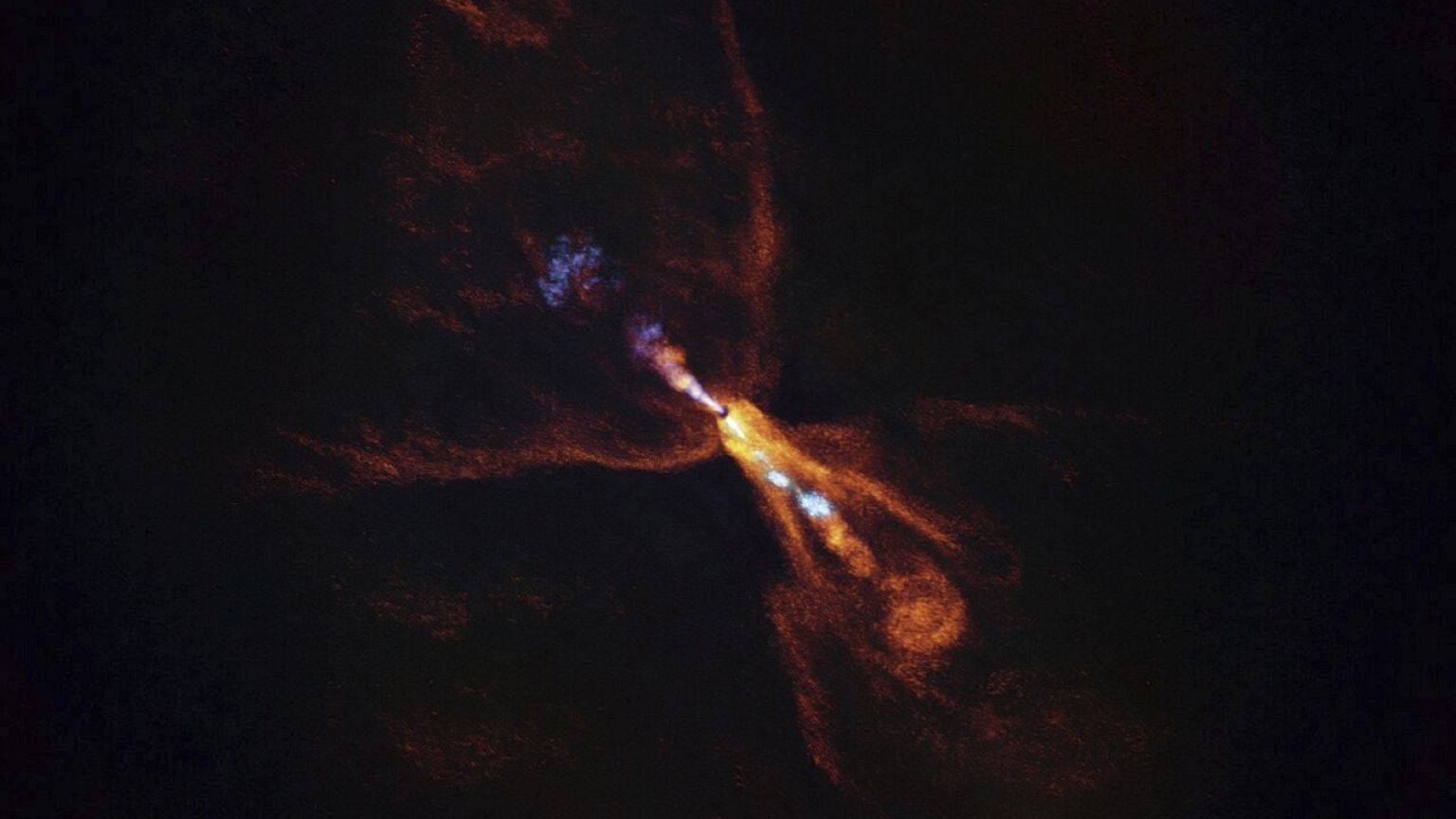

Copyright ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/M. McClure et al. via AP Photo

By Euronews with AP

Published on 16/07/2025

In a cosmic first, scientists identified signs of early planet formation by looking deep into the gas disk around a baby star far outside our solar system.

Astronomers have discovered the earliest seeds of rocky planets forming in the gas around a baby sun-like star, providing a precious peek into the dawn of our own solar system.

It’s an unprecedented snapshot of “time zero,” scientists reported Wednesday, when new worlds begin to gel.

“We’ve captured a direct glimpse of the hot region where rocky planets like Earth are born around young protostars," said Leiden Observatory’s Melissa McClure from the Netherlands, who led the international research team.

“For the first time, we can conclusively say that the first steps of planet formation are happening right now”.

The observations offer a unique glimpse into the inner workings of an emerging planetary system, said the University of Chicago’s Fred Ciesla, who was not involved in the study appearing in the journal Nature.

“This is one of the things we’ve been waiting for. Astronomers have been thinking about how planetary systems form for a long period of time," Ciesla said.

“There's a rich opportunity here”.

Related

How astronomers caught a glimpse

NASA’s Webb Space Telescope and the European Southern Observatory in Chile teamed up to unveil these early nuggets of planetary formation around the young star known as HOPS-315.

It’s a yellow dwarf in the making like the sun, yet much younger at 100,000 to 200,000 years old and some 1,370 light-years away. A single light-year is six trillion miles.

In a cosmic first, McClure and her team stared deep into the gas disk around the baby star and detected solid specks condensing — signs of early planet formation. A gap in the outer part of the disk gave allowed them to gaze inside, thanks to the way the star tilts toward Earth.

They detected silicon monoxide gas as well as crystalline silicate minerals, the ingredients for what’s believed to be the first solid materials to form in our solar system more than 4.5 billion years ago.

The action is unfolding in a location comparable to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter containing the leftover building blocks of our solar system’s planets.

The condensing of hot minerals was never detected before around other young stars, “so we didn’t know if it was a universal feature of planet formation or a weird feature of our solar system,” McClure said in an email.

“Our study shows that it could be a common process during the earliest stage of planet formation”.

First evidence of planetary origins

While other research has looked at younger gas disks and, more commonly, mature disks with potential planet wannabes, there’s been no specific evidence for the start of planet formation until now, McClure said.

In a stunning picture taken by the ESO's Alma telescope network, the emerging planetary system resembles a lightning bug glowing against the black void.

RelatedBehind the scenes on launch day for Biomass, ESA's latest mission | Euronews Tech Talks

It’s impossible to know how many planets might form around HOPS-315. With a gas disk as massive as the sun’s might have been, it could also wind up with eight planets a million or more years from now, according to McClure.

Merel van ’t Hoff, a co-author and assistant professor at Purdue University in the US, is eager to find more budding planetary systems. By casting a wider net, astronomers can look for similarities and determine which processes might be crucial to forming Earth-like worlds, she said.

“Are there Earth-like planets out there or are we like so special that we might not expect it to occur very often?"

NASA to launch SNIFS, Sun’s next trailblazing spectator

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

July will see the launch of the groundbreaking Solar EruptioN Integral Field Spectrograph mission, or SNIFS. Delivered to space via a Black Brant IX sounding rocket, SNIFS will explore the energy and dynamics of the chromosphere, one of the most complex regions of the Sun’s atmosphere. The SNIFS mission’s launch window at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico opens on Friday, July 18.

The chromosphere is located between the Sun’s visible surface, or photosphere, and its outer layer, the corona. The different layers of the Sun’s atmosphere have been researched at length, but many questions persist about the chromosphere. “There’s still a lot of unknowns,” said Phillip Chamberlin, a research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder and principal investigator for the SNIFS mission.

The chromosphere lies just below the corona, where powerful solar flares and massive coronal mass ejections are observed. These solar eruptions are the main drivers of space weather, the hazardous conditions in near-Earth space that threaten satellites and endanger astronauts. The SNIFS mission aims to learn more about how energy is converted and moves through the chromosphere, where it can ultimately power these massive explosions.

“To make sure the Earth is safe from space weather, we really would like to be able to model things,” said Vicki Herde, a doctoral graduate of CU Boulder who worked with Chamberlin to develop SNIFS.

The SNIFS mission is the first ever solar ultraviolet integral field spectrograph, an advanced technology combining an imager and a spectrograph. Imagers capture photos and videos, which are good for seeing the combined light from a large field of view all at once. Spectrographs dissect light into its various wavelengths, revealing which elements are present in the light source, their temperature, and how they’re moving — but only from a single location at a time.

The SNIFS mission combines these two technologies into one instrument.

“It’s the best of both worlds,” said Chamberlin. “You’re pushing the limit of what technology allows us to do.”

By focusing on specific wavelengths, known as spectral lines, the SNIFS mission will help scientists to learn about the chromosphere. These wavelengths include a spectral line of hydrogen that is the brightest line in the Sun’s ultraviolet (UV) spectrum, and two spectral lines from the elements silicon and oxygen. Together, data from these spectral lines will help reveal how the chromosphere connects with upper atmosphere by tracing how solar material and energy move through it.

The SNIFS mission will be carried into space by a sounding rocket. These rockets are effective tools for launching and carrying space experiments and offer a valuable opportunity for hands-on experience, particularly for students and early-career researchers.

“You can really try some wild things,” Herde said. “It gives the opportunity to allow students to touch the hardware.”

Chamberlin emphasized how beneficial these types of missions can be for science and engineering students like Herde, or the next generation of space scientists, who “come with a lot of enthusiasm, a lot of new ideas, new techniques,” he said.

The entirety of the SNIFS mission will likely last up to 15 minutes. After launch, the sounding rocket is expected to take 90 seconds to make it to space and point toward the Sun, seven to eight minutes to perform the experiment on the chromosphere, and three to five minutes to return to Earth’s surface.

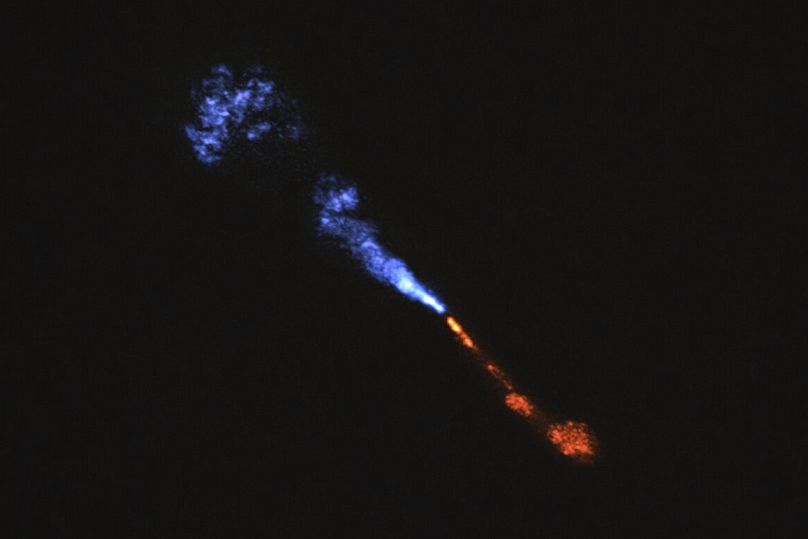

A previous sounding rocket launch from the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. This mission carried a copy of the Extreme Ultraviolet Variability Experiment (EVE).

Credit: NASA/University of Colorado Boulder, Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics/James Mason

The rocket will drift around 70 to 80 miles (112 to 128 kilometers) from the launchpad before its return, so mission contributors must ensure it will have a safe place to land. White Sands, a largely empty desert, is ideal.

Herde, who spent four years working on the rocket, expressed her immense excitement for the launch. “This has been my baby.”

By Harper Lawson

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Method of Research

Experimental study

New cryogenic shape memory alloy designed for outer space

image:

Mechanical heat switch using Cu-Al-Mn shape memory alloy

view moreCredit: Shunsuke Sato, Hirobumi Tobe, Kenichiro Sawada, Chihiro Tokoku, Takao Nakagawa, Eiichi Sato, Yoshikazu Araki, Sheng Xu, Xiao Xu, Toshihiro Omori, Ryosuke Kainuma

A study led by Tohoku University, Iwate University, The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), National Astronomical Observation of Japan, Tokyo City University, and Kyoto University developed a novel copper-based alloy that exhibits a special shape memory effect at temperatures as low as -200°C. Shape memory alloys can be deformed into different shapes when cold, but will revert back to their original shape when heated (as if "remembering" their default state, like memory foam). This exciting new alloy has the potential to be used for space equipment and hydrogen-related technologies, where challenging, cold environments below -100°C are the norm.

Previously studied shape memory alloys using Ni-Ti could not maintain their shape memory ability below -20°C, despite their otherwise practical characteristics. In contrast, the known existing shape memory alloys that can actually operate below -100°C aren't suitable for practical implementation. This study met the challenge of finding the first functional actuator material capable of large work output at temperatures below -100°C. Actuators are components that turn some sort of input into mechanical energy (movement). They can be found not only in machines bound for outer space, but in everyday devices all around us.

The team of researchers prototyped a mechanical heat switch using a new alloy (Cu-Al-Mn) as an actuator. This switch was shown to operate effectively at -170°C, controlling heat transfer by switching between contact and non-contact states based on temperature changes. The operating temperature of the alloy can be adjusted by modifying its composition.

"We were very happy when we saw that it worked at -170°C," remarks Toshihiro Omori (Tohoku University), "Other shape memory alloys simply can't do this."

The Cu-Al-Mn alloy is the first actuator material capable of large output at temperatures below -100°C. This development paves the way for the realization of high-performance actuators that can operate even under cryogenic conditions, which could not be realized before. Potential applications include a reliable mechanical heat switch for cooling system in space telescopes. The simplicity and compactness of such mechanical heat switches make them a crucial technology for future space missions and for advancing carbon-neutral initiatives like hydrogen transportation and storage.

Strain change during cooling and heating under stress in Cu-Al-Mn-based alloy

Comparison of work output with several actuator materials and the Cu-Al-Mn shape memory alloys.

(a) Mechanical heat switch using shape memory alloy and (b) temperature change during heating ©Shunsuke Sato et al.

Credit

Shunsuke Sato, Hirobumi Tobe, Kenichiro Sawada, Chihiro Tokoku, Takao Nakagawa, Eiichi Sato, Yoshikazu Araki, Sheng Xu, Xiao Xu, Toshihiro Omori, Ryosuke Kainuma

Journal

Communications Engineering

Article Title

Shape memory alloys for cryogenic actuators

Article Publication Date

16-Jul-2025

No comments:

Post a Comment