How Hindu supremacists are tearing India apart

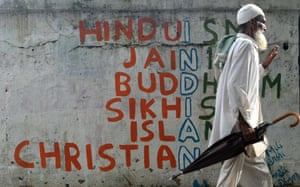

For seven decades, India has been held together by its constitution, which promises equality to all. But Narendra Modi’s BJP is remaking the nation into one where some people count as more Indian than others.

By Samanth Subramanian Thu 20 Feb 2020 The long read

Soon after the violence began, on 5 January, Aamir was standing outside a residence hall in Jawaharlal Nehru University in south Delhi. Aamir, a PhD student, is Muslim, and he asked to be identified only by his first name. He had come to return a book to a classmate when he saw 50 or 60 people approaching the building. They carried metal rods, cricket bats and rocks. One swung a sledgehammer. They were yelling slogans: “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” was a common one. Later, Aamir learned that they had spent the previous half-hour assaulting a gathering of teachers and students down the road. Their faces were masked, but some were still recognisable as members of a Hindu nationalist student group that has become increasingly powerful over the past few years.

The group, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidya Parishad (ABVP), is the youth wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Founded 94 years ago by men who were besotted with Mussolini’s fascists, the RSS is the holding company of Hindu supremacism: of Hindutva, as it’s called. Given its role and its size, it is difficult to find an analogue for the RSS anywhere in the world. In nearly every faith, the source of conservative theology is its hierarchical, centrally organised clergy; that theology is recast into a project of religious statecraft elsewhere, by other parties. Hinduism, though, has no principal church, no single pontiff, nobody to ordain or rule. The RSS has appointed itself as both the arbiter of theological meaning and the architect of a Hindu nation-state. It has at least 4 million volunteers, who swear oaths of allegiance and take part in quasi-military drills.

The word often used to describe the RSS is “paramilitary”. In its near-century of existence, it has been accused of plotting assassinations, stoking riots against minorities and acts of terrorism. (Mahatma Gandhi was shot dead in 1948 by an RSS man, although the RSS claims he had left the organisation by then.) The RSS doesn’t, by itself, engage in electoral politics. But among its affiliated groups is the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), the party that has governed India for the past six years, and that has, under the prime minister Narendra Modi, been remaking India into an authoritarian, Hindu nationalist state.

It was nearly 7pm when Aamir saw the approaching mob. At that time in mid-winter, the campus of JNU, perhaps India’s most influential state-run university, is unnervingly dark. It spreads over more than 400 hectares of wooded land, sealed off by a wall from the rest of south Delhi. Residence halls sit in groves of acacia and borage. To get anywhere from the gate requires a bicycle, an auto rickshaw or a long walk. The university’s 8,000 students appear to occupy a remote world unto themselves. Since its founding in 1969, though, JNU has functioned as a microcosm of national politics. The ideologies of its students and faculty – exhibited in its hyperactive student politics – have traditionally been liberal, leftist and secular. Through its academics, JNU frequently moulded government policy; its graduates went into the media, major non-profits, the law or leftist parties. Over the years, JNU has stood for much of what the conservative, ethnocentric BJP has resented about the country it governs today. The university has been like a stone in the boot of the BJP, hobbling the party with every step.

When he spotted the mob, Aamir ran into the dorms, up the stairs and into his friend’s room. They locked the door, then hid on the balcony. They heard the attackers shattering panes of glass, barging into rooms and beating students. Aamir silenced his phone. “I was sure they’d break my arms and legs if they caught me,” he said. The mob had come with clear intent, targeting students and faculty who had been critical of the BJP: a Muslim student from Kashmir, teachers with ties to the political left, members of groups that championed underprivileged castes. The president of the JNU student union, Aishe Ghosh, received a deep gash to her head and her arm was broken. The rooms of ABVP allies, though, were spared.

Later, it emerged that the university’s own cadre of ABVP had been bolstered by students from other universities – and perhaps by people who weren’t students at all, people who were just RSS muscle. Rohit Azad, who has spent two decades at the university, first as a student and then a professor of economics, told me that although he had seen his share of violence between student groups, “this thing – this act of bringing in attackers from outside – that was unprecedented”. It was as if the Young Republicans had invited some alt-right thugs to join them in running amok through Berkeley, beating up black and Hispanic students, Young Democrats and anyone who’d expressed support for Bernie Sanders.

Play Video

1:32 Masked mob storms top Delhi university, injuring staff and students – videoVideos of the attacks leaked out through social media in real time. The police were called, but they didn’t move to stop the violence. Instead, a posse of policemen installed itself at JNU’s gate, allowing no one in. Yogendra Yadav, a political activist, arrived at the gate at 9pm. Ninety minutes later, the attackers emerged, still masked and armed. Even then, the police detained no one. Instead, they were permitted to walk away as if nothing had happened. When Yadav’s colleague took photos, Yadav was set upon by a knot of men, knocked down and kicked in the face. The police did nothing. Later, from a video, Yadav identified a local ABVP official among those who had hit him. In a statement, the ABVP blamed the attacks on “leftist goons,” but on television members admitted that the masked, armed men and women on campus were part of the ABVP. Still, the Delhi police pressed no charges. “The police gave the goons cover, gave them free rein on campus,” Yadav said. A JNU professor went further, claiming that: “The police are complicit.”

The onslaught on JNU marked the middle of a season of nationwide protest, provoked by a new law. The Citizenship Amendment Act, passed by parliament on 11 December 2019, provides a fast track to citizenship for refugees fleeing into India from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Refugees of every south Asian faith are eligible – every faith, that is, except Islam. It is a policy that fits neatly with the RSS and the BJP’s demonisation of Muslims, India’s largest religious minority. To votaries of Hindutva, the country is best served if it is expunged of Islam. The act was both a loud signal of that ambition and a handy tool to help achieve it.

Since December, millions of Indians have turned out on to the streets to object to this vision of their country. The government has fought them by banning gatherings, shutting off mobile internet services, detaining people arbitrarily, or worse. After protests flared at Jamia Millia Islamia, an Islamic university in Delhi, cops fired teargas and live rounds, assaulted students and trashed the library. As demonstrations spread across the state of Uttar Pradesh, police raided and vandalised Muslim homes by way of reprisal. Detainees in custody were beaten; one man reported hearing screams in a police station all night long. (In various statements, the police claimed to be acting in self defence, or to prevent violence, or to root out conspiracy.) At least 20 protesters died of bullet wounds. Police officials denied firing at the crowds, even though the police carried the only visible guns at these rallies.

Still, the protests have persisted well into February. At Shaheen Bagh, a neighbourhood in south-eastern Delhi, hundreds of thousands of people have turned up over nine weeks to take part in an indefinite sit-in. The BJP has taken a ruthless view of all this dissent. On one occasion, Yogi Adityanath, a Hindu cleric who is chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, said: “If they won’t understand words, they’ll understand bullets.” One of Modi’s ministers used “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” as a call-and-response at a rally – the same slogan the ABVP had raised in JNU.

In its 72 years as a free country, India has never faced a more serious crisis. Already its institutions – its courts, much of its media, its investigative agencies, its election commission – have been pressured to fall in line with Modi’s policies. The political opposition is withered and infirm. More is in the offing: the idea of Hindutva, in its fullest expression, will ultimately involve undoing the constitution and unravelling the fabric of liberal democracy. It will have to; constitutional niceties aren’t compatible with the BJP’s blueprint for a country in which people are graded and assessed according to their faith. The ferment gripping India since the passage of the citizenship act – the fever of the protests, the brutality of the police, the viciousness of the politics – has only reflected how existentially high the stakes have become.

The RSS and the BJP’s success, over the past six years, is owed in part to its adept poisoning of the public discourse. Politicians, indoctrinated media outlets and squadrons of social media trolls lie, polarise and demonise all day long. Among their stratagems is the invention of categories of abuse for their opponents, to convey with a single label why such people should not be trusted to have India’s interests at heart. “Presstitute” is one, applied to liberal journalists to accuse them of selling their coverage for money or influence. “Sickular” is another, born of the RSS’s opinion that Indian secularism is a demented version of minority appeasement.

The term “JNU type” refers to leftists of every stripe – from Maoists yearning for the revolution, to moderates who abhor Hindutva. Traditionally, JNU has specialised in the humanities, so “JNU types” also came to be scorned for their soft humanism – for their opposition to capital punishment, to the army’s human-rights abuses, or to the state’s repressions in Kashmir. All while studying for years and years on the government’s dime, the BJP’s supporters complain. It’s enough to slot JNU types into the mother category: “anti-national”.

Soon after the violence began, on 5 January, Aamir was standing outside a residence hall in Jawaharlal Nehru University in south Delhi. Aamir, a PhD student, is Muslim, and he asked to be identified only by his first name. He had come to return a book to a classmate when he saw 50 or 60 people approaching the building. They carried metal rods, cricket bats and rocks. One swung a sledgehammer. They were yelling slogans: “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” was a common one. Later, Aamir learned that they had spent the previous half-hour assaulting a gathering of teachers and students down the road. Their faces were masked, but some were still recognisable as members of a Hindu nationalist student group that has become increasingly powerful over the past few years.

The group, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidya Parishad (ABVP), is the youth wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Founded 94 years ago by men who were besotted with Mussolini’s fascists, the RSS is the holding company of Hindu supremacism: of Hindutva, as it’s called. Given its role and its size, it is difficult to find an analogue for the RSS anywhere in the world. In nearly every faith, the source of conservative theology is its hierarchical, centrally organised clergy; that theology is recast into a project of religious statecraft elsewhere, by other parties. Hinduism, though, has no principal church, no single pontiff, nobody to ordain or rule. The RSS has appointed itself as both the arbiter of theological meaning and the architect of a Hindu nation-state. It has at least 4 million volunteers, who swear oaths of allegiance and take part in quasi-military drills.

The word often used to describe the RSS is “paramilitary”. In its near-century of existence, it has been accused of plotting assassinations, stoking riots against minorities and acts of terrorism. (Mahatma Gandhi was shot dead in 1948 by an RSS man, although the RSS claims he had left the organisation by then.) The RSS doesn’t, by itself, engage in electoral politics. But among its affiliated groups is the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), the party that has governed India for the past six years, and that has, under the prime minister Narendra Modi, been remaking India into an authoritarian, Hindu nationalist state.

It was nearly 7pm when Aamir saw the approaching mob. At that time in mid-winter, the campus of JNU, perhaps India’s most influential state-run university, is unnervingly dark. It spreads over more than 400 hectares of wooded land, sealed off by a wall from the rest of south Delhi. Residence halls sit in groves of acacia and borage. To get anywhere from the gate requires a bicycle, an auto rickshaw or a long walk. The university’s 8,000 students appear to occupy a remote world unto themselves. Since its founding in 1969, though, JNU has functioned as a microcosm of national politics. The ideologies of its students and faculty – exhibited in its hyperactive student politics – have traditionally been liberal, leftist and secular. Through its academics, JNU frequently moulded government policy; its graduates went into the media, major non-profits, the law or leftist parties. Over the years, JNU has stood for much of what the conservative, ethnocentric BJP has resented about the country it governs today. The university has been like a stone in the boot of the BJP, hobbling the party with every step.

When he spotted the mob, Aamir ran into the dorms, up the stairs and into his friend’s room. They locked the door, then hid on the balcony. They heard the attackers shattering panes of glass, barging into rooms and beating students. Aamir silenced his phone. “I was sure they’d break my arms and legs if they caught me,” he said. The mob had come with clear intent, targeting students and faculty who had been critical of the BJP: a Muslim student from Kashmir, teachers with ties to the political left, members of groups that championed underprivileged castes. The president of the JNU student union, Aishe Ghosh, received a deep gash to her head and her arm was broken. The rooms of ABVP allies, though, were spared.

Later, it emerged that the university’s own cadre of ABVP had been bolstered by students from other universities – and perhaps by people who weren’t students at all, people who were just RSS muscle. Rohit Azad, who has spent two decades at the university, first as a student and then a professor of economics, told me that although he had seen his share of violence between student groups, “this thing – this act of bringing in attackers from outside – that was unprecedented”. It was as if the Young Republicans had invited some alt-right thugs to join them in running amok through Berkeley, beating up black and Hispanic students, Young Democrats and anyone who’d expressed support for Bernie Sanders.

Play Video

1:32 Masked mob storms top Delhi university, injuring staff and students – videoVideos of the attacks leaked out through social media in real time. The police were called, but they didn’t move to stop the violence. Instead, a posse of policemen installed itself at JNU’s gate, allowing no one in. Yogendra Yadav, a political activist, arrived at the gate at 9pm. Ninety minutes later, the attackers emerged, still masked and armed. Even then, the police detained no one. Instead, they were permitted to walk away as if nothing had happened. When Yadav’s colleague took photos, Yadav was set upon by a knot of men, knocked down and kicked in the face. The police did nothing. Later, from a video, Yadav identified a local ABVP official among those who had hit him. In a statement, the ABVP blamed the attacks on “leftist goons,” but on television members admitted that the masked, armed men and women on campus were part of the ABVP. Still, the Delhi police pressed no charges. “The police gave the goons cover, gave them free rein on campus,” Yadav said. A JNU professor went further, claiming that: “The police are complicit.”

The onslaught on JNU marked the middle of a season of nationwide protest, provoked by a new law. The Citizenship Amendment Act, passed by parliament on 11 December 2019, provides a fast track to citizenship for refugees fleeing into India from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Refugees of every south Asian faith are eligible – every faith, that is, except Islam. It is a policy that fits neatly with the RSS and the BJP’s demonisation of Muslims, India’s largest religious minority. To votaries of Hindutva, the country is best served if it is expunged of Islam. The act was both a loud signal of that ambition and a handy tool to help achieve it.

Since December, millions of Indians have turned out on to the streets to object to this vision of their country. The government has fought them by banning gatherings, shutting off mobile internet services, detaining people arbitrarily, or worse. After protests flared at Jamia Millia Islamia, an Islamic university in Delhi, cops fired teargas and live rounds, assaulted students and trashed the library. As demonstrations spread across the state of Uttar Pradesh, police raided and vandalised Muslim homes by way of reprisal. Detainees in custody were beaten; one man reported hearing screams in a police station all night long. (In various statements, the police claimed to be acting in self defence, or to prevent violence, or to root out conspiracy.) At least 20 protesters died of bullet wounds. Police officials denied firing at the crowds, even though the police carried the only visible guns at these rallies.

Still, the protests have persisted well into February. At Shaheen Bagh, a neighbourhood in south-eastern Delhi, hundreds of thousands of people have turned up over nine weeks to take part in an indefinite sit-in. The BJP has taken a ruthless view of all this dissent. On one occasion, Yogi Adityanath, a Hindu cleric who is chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, said: “If they won’t understand words, they’ll understand bullets.” One of Modi’s ministers used “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” as a call-and-response at a rally – the same slogan the ABVP had raised in JNU.

In its 72 years as a free country, India has never faced a more serious crisis. Already its institutions – its courts, much of its media, its investigative agencies, its election commission – have been pressured to fall in line with Modi’s policies. The political opposition is withered and infirm. More is in the offing: the idea of Hindutva, in its fullest expression, will ultimately involve undoing the constitution and unravelling the fabric of liberal democracy. It will have to; constitutional niceties aren’t compatible with the BJP’s blueprint for a country in which people are graded and assessed according to their faith. The ferment gripping India since the passage of the citizenship act – the fever of the protests, the brutality of the police, the viciousness of the politics – has only reflected how existentially high the stakes have become.

The RSS and the BJP’s success, over the past six years, is owed in part to its adept poisoning of the public discourse. Politicians, indoctrinated media outlets and squadrons of social media trolls lie, polarise and demonise all day long. Among their stratagems is the invention of categories of abuse for their opponents, to convey with a single label why such people should not be trusted to have India’s interests at heart. “Presstitute” is one, applied to liberal journalists to accuse them of selling their coverage for money or influence. “Sickular” is another, born of the RSS’s opinion that Indian secularism is a demented version of minority appeasement.

The term “JNU type” refers to leftists of every stripe – from Maoists yearning for the revolution, to moderates who abhor Hindutva. Traditionally, JNU has specialised in the humanities, so “JNU types” also came to be scorned for their soft humanism – for their opposition to capital punishment, to the army’s human-rights abuses, or to the state’s repressions in Kashmir. All while studying for years and years on the government’s dime, the BJP’s supporters complain. It’s enough to slot JNU types into the mother category: “anti-national”.

The Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) campus in New Delhi.

Photograph: Hindustan Times/Getty

In its earliest years, JNU soaked up the ideology of the man it was named after – Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister – and of his party, the Congress. It was still only a generation since independence, and Nehru and the Congress, having led the freedom struggle, exerted enormous moral authority. The university’s ethos and its very curriculum were built on Nehru’s values, says Rakesh Batabyal, the author of JNU: The Making of a University. It was secular in its worldview, left of centre in its economics and technocratic in its thinking on policy. “Students came from all over the country,” Batabyal told me. “There was a pluralism to the university that Nehru wanted for India.”

Over the next few decades, the locus of power in student politics migrated further leftwards, into groups that allied themselves with national communist parties. The ABVP, which opposed all these -isms – secularism, pluralism, socialism, communism – remained on the margins, just like its counterparts in national politics. The Hindu right had done nothing of note during the freedom struggle; in fact, the RSS didn’t take part in the mass movements that forced the British out of India. For almost half a century after independence, the political parties backed by the RSS remained in the political wilderness. “They used to say that, back in the 1980s, if you were a supporter at an ABVP event, you went to it with a blanket covering your face,” Azad, the JNU professor, told me. “That was how embarrassing it was considered to be.”

Then a mosque was destroyed, and India changed. For years, the RSS had claimed that the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in the town of Ayodhya, stood on the very spot where the Hindu deity Ram was born. The location warranted a temple, the RSS declared, not a mosque built by an invading Muslim king. Late in 1990, a BJP leader toured India’s heartland for two months, in an air-conditioned Toyota mocked up to resemble a chariot, to rouse Hindus to demand that a temple replace the mosque. (The man who sat in the Toyota’s cabin, serving as the rally’s logistician, was Narendra Modi.) In December 1992, a crowd of men from the RSS and BJP razed the mosque, watched but unhindered by the police. In the following weeks, religious riots erupted across India, particularly in Mumbai. Two thousand people were killed. The BJP’s obsession with the Babri mosque was bloody and divisive, but it also earned them new political capital. In 1996, the BJP came to power for the first time.

On the campus of JNU, in tidy parallel, the fortunes of the ABVP bloomed: it won its first seat in the student union in 1992, three key union posts in 1996, and in 2000, the presidency of the union itself. The man who won that plum post, Sandeep Mahapatra, entered JNU in 1997 – a time, he told me, when the ABVP’s supporters were proud and vocal about their allegiances. No one wrapped blankets around their faces any more. Part of the reason for the ABVP’s rise, Mahapatra said, was fatigue with leftist ideas. “The Soviet Union had disintegrated. Even there, the left had been defeated,” Mahapatra, now a lawyer in Delhi, said. “The students thought there was some space for nationalist thought.”

Photograph: Hindustan Times/Getty

In its earliest years, JNU soaked up the ideology of the man it was named after – Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister – and of his party, the Congress. It was still only a generation since independence, and Nehru and the Congress, having led the freedom struggle, exerted enormous moral authority. The university’s ethos and its very curriculum were built on Nehru’s values, says Rakesh Batabyal, the author of JNU: The Making of a University. It was secular in its worldview, left of centre in its economics and technocratic in its thinking on policy. “Students came from all over the country,” Batabyal told me. “There was a pluralism to the university that Nehru wanted for India.”

Over the next few decades, the locus of power in student politics migrated further leftwards, into groups that allied themselves with national communist parties. The ABVP, which opposed all these -isms – secularism, pluralism, socialism, communism – remained on the margins, just like its counterparts in national politics. The Hindu right had done nothing of note during the freedom struggle; in fact, the RSS didn’t take part in the mass movements that forced the British out of India. For almost half a century after independence, the political parties backed by the RSS remained in the political wilderness. “They used to say that, back in the 1980s, if you were a supporter at an ABVP event, you went to it with a blanket covering your face,” Azad, the JNU professor, told me. “That was how embarrassing it was considered to be.”

Then a mosque was destroyed, and India changed. For years, the RSS had claimed that the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in the town of Ayodhya, stood on the very spot where the Hindu deity Ram was born. The location warranted a temple, the RSS declared, not a mosque built by an invading Muslim king. Late in 1990, a BJP leader toured India’s heartland for two months, in an air-conditioned Toyota mocked up to resemble a chariot, to rouse Hindus to demand that a temple replace the mosque. (The man who sat in the Toyota’s cabin, serving as the rally’s logistician, was Narendra Modi.) In December 1992, a crowd of men from the RSS and BJP razed the mosque, watched but unhindered by the police. In the following weeks, religious riots erupted across India, particularly in Mumbai. Two thousand people were killed. The BJP’s obsession with the Babri mosque was bloody and divisive, but it also earned them new political capital. In 1996, the BJP came to power for the first time.

On the campus of JNU, in tidy parallel, the fortunes of the ABVP bloomed: it won its first seat in the student union in 1992, three key union posts in 1996, and in 2000, the presidency of the union itself. The man who won that plum post, Sandeep Mahapatra, entered JNU in 1997 – a time, he told me, when the ABVP’s supporters were proud and vocal about their allegiances. No one wrapped blankets around their faces any more. Part of the reason for the ABVP’s rise, Mahapatra said, was fatigue with leftist ideas. “The Soviet Union had disintegrated. Even there, the left had been defeated,” Mahapatra, now a lawyer in Delhi, said. “The students thought there was some space for nationalist thought.”

The demolishing of the Babri Masjid mosque in 1992.

Photograph: India Picture/Alamy

The 90s were a decade of disillusionment with socialism and communism, and so too in JNU. Mahapatra’s opponents, he said, “were always talking about abstract things – what Mao had said, or what Marx had said”. The ABVP, for its part, mined the same faultlines on campus that the BJP exploited in Indian society. “We talked about Kashmir, about the Ram temple, about the Hindu nation.” These were all crucial items on the RSS wishlist: to take full possession of the disputed region of Kashmir, defeating Pakistan in the process; to build the temple in Ayodhya; to give Hindus primacy in India. Dust-ups and brawls between student parties, Mahapatra said, were common. Once, while speaking on a stage, he was injured by stones hurled at him by his opponents.

In the 21st century, the tracks of India’s politics and JNU’s politics diverged somewhat. Across the country, the old communist parties fell out of favour. In West Bengal, a citadel of the left, the communists were voted out of the state government in 2011, having held it for 34 years. The Congress, run as a family shop by Nehru’s dynasty, turned complacent and highly corrupt. In the 2014 parliamentary elections, it won just 44 seats – a historic low. The slide was swift and brutal. On campus, the leftist student groups splintered; new caste-based factions arose. But they all decided, Mahapatra said, to band together against the ABVP. Its numbers grew, but its electoral triumphs stalled. There hasn’t been an ABVP union president since Mahapatra, but the group’s power and authority have expanded in ways that tracked the havoc let loose by the Hindu right under Modi.

When Modi won his first term as prime minister in 2014, it was difficult to know how to read the result. Were those who voted for the BJP frustrated with the alternatives, or did they believe Modi to be the economic miracle-worker he claimed to be? Had they simply chosen to disregard the fact that he had allowed mobs of Hindu fanatics to murder hundreds of Muslims in riots during his chief ministership of Gujarat in 2002, or did they actively approve of this overt anti-Muslim agenda?

Only after Modi settled into power did many BJP voters begin to clearly voice their sympathies for Hindutva. These revelations felt sudden and shocking, to the point that you wondered if these voters had silently longed for a pure Hindu nation well before Modi. Relationships ruptured the way they did after Trump’s election or the Brexit referendum. Families bickered on WhatsApp groups, and friends fell out. “Before 2014, you’d have found a pro-ABVP student and a pro-left student who were friends with each other,” Cheri Che, a PhD student in history, told me. “After 2014, that was increasingly difficult.”

At JNU, the ABVP’s influence swelled. Che claimed that faculty and administration positions were filled with people who had RSS or ABVP connections. At one point, he said, the “wardens” – or supervisors – of nearly every residence hall were shunted out and replaced with ABVP sympathisers. Beyond the campus, Hindu nationalists felt so empowered that they formed gangs to lynch Muslims and lower-caste Hindus, on flimsy suspicions that their victims were smuggling cows or in possession of beef. (In Hinduism, the cow is revered as sacred.) Since 2014, at least 44 people have been murdered and 280 injured. The gangs acted with impunity, sometimes filming themselves, as if they’d never be prosecuted – and they were proven correct. In one Uttar Pradesh town, a Muslim man, beaten so badly that he would eventually die, was dragged injured along the ground. A photo showed a policeman clearing a path through the crowd as the mob hauled the body behind him.

On the JNU campus, Muslim students felt more and more anxious. On the day in 2017 when Yogi Adityanath, the Hindutva hardliner, was elected chief minister, a Kashmiri Muslim student was walking to a canteen. It was close to midnight. “I saw a guy, a hardcore ABVP supporter,” said the student, who asked not to be named. “As soon as he saw me, he said: ‘Now that Yogi’s here, we’ll cut down and devour the Muslims.’ He said it openly. There were a lot of people standing around. You wouldn’t have heard anything like that earlier.”

In February 2016, Kanhaiya Kumar, a communist who was then the student union’s president, was part of a campus protest against the hanging of a Kashmiri man dubiously convicted of terrorism. The ABVP called in news crews from pro-BJP channels. Over the next few days, these channels aired footage that seemed to show Kumar and others yelling slogans calling for the break-up of India. For viewers, the videos confirmed what they already suspected: that JNU was a hothouse of treason. A few weeks later, the videos were found to have been doctored.

Regardless, the BJP’s leaders kept referring to JNU’s students – and to anyone who supported them – as “anti-nationals” and traitors. The Delhi police arrested Kumar and charged him under a century-old sedition law. When the police took him to the courthouse for his hearing, they encountered a mob of dozens of lawyers and at least one BJP legislator hollering slogans. “Shoot him!” they shouted. Then, inside the courthouse, while the police stood by, the mob beat Kumar up. Afterwards, a news report said, one of the attackers claimed with satisfaction: “Our job is done.”

Photograph: India Picture/Alamy

The 90s were a decade of disillusionment with socialism and communism, and so too in JNU. Mahapatra’s opponents, he said, “were always talking about abstract things – what Mao had said, or what Marx had said”. The ABVP, for its part, mined the same faultlines on campus that the BJP exploited in Indian society. “We talked about Kashmir, about the Ram temple, about the Hindu nation.” These were all crucial items on the RSS wishlist: to take full possession of the disputed region of Kashmir, defeating Pakistan in the process; to build the temple in Ayodhya; to give Hindus primacy in India. Dust-ups and brawls between student parties, Mahapatra said, were common. Once, while speaking on a stage, he was injured by stones hurled at him by his opponents.

In the 21st century, the tracks of India’s politics and JNU’s politics diverged somewhat. Across the country, the old communist parties fell out of favour. In West Bengal, a citadel of the left, the communists were voted out of the state government in 2011, having held it for 34 years. The Congress, run as a family shop by Nehru’s dynasty, turned complacent and highly corrupt. In the 2014 parliamentary elections, it won just 44 seats – a historic low. The slide was swift and brutal. On campus, the leftist student groups splintered; new caste-based factions arose. But they all decided, Mahapatra said, to band together against the ABVP. Its numbers grew, but its electoral triumphs stalled. There hasn’t been an ABVP union president since Mahapatra, but the group’s power and authority have expanded in ways that tracked the havoc let loose by the Hindu right under Modi.

When Modi won his first term as prime minister in 2014, it was difficult to know how to read the result. Were those who voted for the BJP frustrated with the alternatives, or did they believe Modi to be the economic miracle-worker he claimed to be? Had they simply chosen to disregard the fact that he had allowed mobs of Hindu fanatics to murder hundreds of Muslims in riots during his chief ministership of Gujarat in 2002, or did they actively approve of this overt anti-Muslim agenda?

Only after Modi settled into power did many BJP voters begin to clearly voice their sympathies for Hindutva. These revelations felt sudden and shocking, to the point that you wondered if these voters had silently longed for a pure Hindu nation well before Modi. Relationships ruptured the way they did after Trump’s election or the Brexit referendum. Families bickered on WhatsApp groups, and friends fell out. “Before 2014, you’d have found a pro-ABVP student and a pro-left student who were friends with each other,” Cheri Che, a PhD student in history, told me. “After 2014, that was increasingly difficult.”

At JNU, the ABVP’s influence swelled. Che claimed that faculty and administration positions were filled with people who had RSS or ABVP connections. At one point, he said, the “wardens” – or supervisors – of nearly every residence hall were shunted out and replaced with ABVP sympathisers. Beyond the campus, Hindu nationalists felt so empowered that they formed gangs to lynch Muslims and lower-caste Hindus, on flimsy suspicions that their victims were smuggling cows or in possession of beef. (In Hinduism, the cow is revered as sacred.) Since 2014, at least 44 people have been murdered and 280 injured. The gangs acted with impunity, sometimes filming themselves, as if they’d never be prosecuted – and they were proven correct. In one Uttar Pradesh town, a Muslim man, beaten so badly that he would eventually die, was dragged injured along the ground. A photo showed a policeman clearing a path through the crowd as the mob hauled the body behind him.

On the JNU campus, Muslim students felt more and more anxious. On the day in 2017 when Yogi Adityanath, the Hindutva hardliner, was elected chief minister, a Kashmiri Muslim student was walking to a canteen. It was close to midnight. “I saw a guy, a hardcore ABVP supporter,” said the student, who asked not to be named. “As soon as he saw me, he said: ‘Now that Yogi’s here, we’ll cut down and devour the Muslims.’ He said it openly. There were a lot of people standing around. You wouldn’t have heard anything like that earlier.”

In February 2016, Kanhaiya Kumar, a communist who was then the student union’s president, was part of a campus protest against the hanging of a Kashmiri man dubiously convicted of terrorism. The ABVP called in news crews from pro-BJP channels. Over the next few days, these channels aired footage that seemed to show Kumar and others yelling slogans calling for the break-up of India. For viewers, the videos confirmed what they already suspected: that JNU was a hothouse of treason. A few weeks later, the videos were found to have been doctored.

Regardless, the BJP’s leaders kept referring to JNU’s students – and to anyone who supported them – as “anti-nationals” and traitors. The Delhi police arrested Kumar and charged him under a century-old sedition law. When the police took him to the courthouse for his hearing, they encountered a mob of dozens of lawyers and at least one BJP legislator hollering slogans. “Shoot him!” they shouted. Then, inside the courthouse, while the police stood by, the mob beat Kumar up. Afterwards, a news report said, one of the attackers claimed with satisfaction: “Our job is done.”

Students protesting against the arrest of union president

Kanhaiya Kumar at the JNU campus in February 2016.

Photograph: Hindustan Times/Getty

After the February 2016 protest, the Kashmiri JNU student learned that police had visited his home in Srinagar, in Kashmir, and taken down a host of details about him and his family. He hadn’t even been at the protest, he said. Then he discovered that every Kashmiri student he knew in JNU had a similar story to tell. It shook him. “We decided – a group of us – that we’d just stay out of things having to do with politics,” he said. “We’re vulnerable here.” A little over a year ago, when he was going to the campus library one morning, he saw a big truck filled with people shouting slogans about the Ram temple in Ayodhya. Out of a set of loudspeakers on the truck, music from the Hindutva songbook poured out. Accompanying the truck, he said, were “people on bikes, people on foot – and they were outsiders, not students,” he said. “I thought: ‘The goons have come inside.’”

In 2016, Modi’s government installed at the head of JNU an engineering professor named M Jagadesh Kumar. The students and the press described Kumar as an RSS loyalist – part of the government’s wider campaign to seed universities and cultural institutions with RSS appointees. Kumar denied any links with the RSS.

On the evening of 5 January, as the attacks on campus escalated, Kumar messaged the police via WhatsApp, according to a police enquiry report. Instead of requesting help in curbing the mob, though, he asked for police to be stationed outside the gate. (Later, to a reporter, he said that he’d wanted campus security to tackle the assaults, which he called “unfortunate.”) Only at 7.45pm did a JNU official ask the police into the campus to intervene, but by then the violence had ended. The attackers were still on the premises hours later, but the university and the police let them leave, as if they’d dropped by for a visit and were now hurrying to catch the last bus home.

Even before the ABVP attacks, JNU had been seething. For weeks, the student union had been aggressively opposing a fee hike, boycotting registrations and forcing classes to be suspended. When the nationwide demonstrations against the citizenship act began, that was folded into the mobilisations on campus. To many students, the JNU administration, the RSS and the BJP were part of the same machine.

By itself, the new law defies India’s constitution, which is a long document steeped in the resolve to treat castes and religions with scrupulous equality. Written between 1946 and 1949, it was an exercise in nation-making – in gluing together a giant modern state from fragmented communities living across the land. To effect this, one of its chief promises was that citizenship would bear no connection to religion. The citizenship act’s exclusion of Muslims violates that promise.

But the act is most menacing when read in tandem with other recent government measures, which in totality aim to redefine who does and does not belong on Indian soil. These measures can be perplexing, even for Indians. For one, some of their functions seem to overlap. For another, they’re constantly referred to by the kind of abbreviations that are unavoidable in Indian life. The Citizenship Amendment Act is the CAA; the National Register of Citizens is the NRC; the National Population Register is the NPR. On Twitter, hashtags about the #CAA-NPR-NRC issue devolve into a thick alphabet soup.

Kanhaiya Kumar at the JNU campus in February 2016.

Photograph: Hindustan Times/Getty

After the February 2016 protest, the Kashmiri JNU student learned that police had visited his home in Srinagar, in Kashmir, and taken down a host of details about him and his family. He hadn’t even been at the protest, he said. Then he discovered that every Kashmiri student he knew in JNU had a similar story to tell. It shook him. “We decided – a group of us – that we’d just stay out of things having to do with politics,” he said. “We’re vulnerable here.” A little over a year ago, when he was going to the campus library one morning, he saw a big truck filled with people shouting slogans about the Ram temple in Ayodhya. Out of a set of loudspeakers on the truck, music from the Hindutva songbook poured out. Accompanying the truck, he said, were “people on bikes, people on foot – and they were outsiders, not students,” he said. “I thought: ‘The goons have come inside.’”

In 2016, Modi’s government installed at the head of JNU an engineering professor named M Jagadesh Kumar. The students and the press described Kumar as an RSS loyalist – part of the government’s wider campaign to seed universities and cultural institutions with RSS appointees. Kumar denied any links with the RSS.

On the evening of 5 January, as the attacks on campus escalated, Kumar messaged the police via WhatsApp, according to a police enquiry report. Instead of requesting help in curbing the mob, though, he asked for police to be stationed outside the gate. (Later, to a reporter, he said that he’d wanted campus security to tackle the assaults, which he called “unfortunate.”) Only at 7.45pm did a JNU official ask the police into the campus to intervene, but by then the violence had ended. The attackers were still on the premises hours later, but the university and the police let them leave, as if they’d dropped by for a visit and were now hurrying to catch the last bus home.

Even before the ABVP attacks, JNU had been seething. For weeks, the student union had been aggressively opposing a fee hike, boycotting registrations and forcing classes to be suspended. When the nationwide demonstrations against the citizenship act began, that was folded into the mobilisations on campus. To many students, the JNU administration, the RSS and the BJP were part of the same machine.

By itself, the new law defies India’s constitution, which is a long document steeped in the resolve to treat castes and religions with scrupulous equality. Written between 1946 and 1949, it was an exercise in nation-making – in gluing together a giant modern state from fragmented communities living across the land. To effect this, one of its chief promises was that citizenship would bear no connection to religion. The citizenship act’s exclusion of Muslims violates that promise.

But the act is most menacing when read in tandem with other recent government measures, which in totality aim to redefine who does and does not belong on Indian soil. These measures can be perplexing, even for Indians. For one, some of their functions seem to overlap. For another, they’re constantly referred to by the kind of abbreviations that are unavoidable in Indian life. The Citizenship Amendment Act is the CAA; the National Register of Citizens is the NRC; the National Population Register is the NPR. On Twitter, hashtags about the #CAA-NPR-NRC issue devolve into a thick alphabet soup.

BJP supporters at a rally in New Delhi in December 2019.

Photograph: Prakash Singh/AFP via Getty Images

The government started to create a register of citizens five years ago, in the north-eastern state of Assam. The riverine deltas and paddy fields of Assam lie across a porous border with Bangladesh, and migrants have crossed in both directions for decades. The arrival of Bangladeshis – many of them Muslims – became a heated political issue in Assam through the 70s and 80s. The migrants were blamed for taking jobs, usurping land and signing up for welfare benefits despite being ineligible for them.

Previous governments, as well as India’s supreme court, had agreed that a citizens’ register was necessary to distinguish migrants from locals. Citizenship isn’t always simple to prove in India; in a country of more than 1 billion people, fewer than 100 million hold passports, while other documents, issued at local levels by corrupt or inefficient officers, can be unreliable. For the BJP, the idea of a citizen’s register served as both a profitable electoral tactic and a religious wedge. In a stump speech in 2014, Modi told an audience in Assam that while Hindu migrants would be accommodated, other “infiltrators” would be sent back to Bangladesh. In April 2019, Amit Shah, now Modi’s home minister, said that Bangladeshi immigrants were “eating the grain that should go to the poor”. They were “termites”, Shah added. The BJP would pick them up, one by one, and “throw them into the Bay of Bengal”.

To get into the register, people had to prove first that an ancestor lived in Assam before 1971 and then that they were related to that ancestor. In a country of spotty electoral rolls and property deeds, of inconsistent name spellings and patchy documentation, this was always going to be difficult. When the registration of citizens began in 2015, Assam scrambled for its papers. Poor families, worried about being rendered stateless, spent their money on lawyers and documents. Some committed suicide. The so-called foreigners’ tribunals, set up to hear appeals, were incentivised to strike people off the register; the more foreigners you identified, the better your chances of staying on the tribunal.

In 2019, a Vice News examination of five of these tribunals found that nine out of 10 cases involved Muslims. Of the Muslims who appealed, 90% were declared illegal immigrants; for Hindus, the figure was 40%. The government plans to round up all these “foreigners” and transport them to fill nearly a dozen internment camps in the state. (One is already being built: a 28,000 sq metre, double-walled complex for 3,000 people, not far from the border with Bhutan. The centre has six watchtowers and a 100-metre-high light tower.) The BJP is so pleased with this process that it wants to compile a pan-Indian register of citizens, extending the exclusionary power of the process across a population of 1.3 billion.

The government started to create a register of citizens five years ago, in the north-eastern state of Assam. The riverine deltas and paddy fields of Assam lie across a porous border with Bangladesh, and migrants have crossed in both directions for decades. The arrival of Bangladeshis – many of them Muslims – became a heated political issue in Assam through the 70s and 80s. The migrants were blamed for taking jobs, usurping land and signing up for welfare benefits despite being ineligible for them.

Previous governments, as well as India’s supreme court, had agreed that a citizens’ register was necessary to distinguish migrants from locals. Citizenship isn’t always simple to prove in India; in a country of more than 1 billion people, fewer than 100 million hold passports, while other documents, issued at local levels by corrupt or inefficient officers, can be unreliable. For the BJP, the idea of a citizen’s register served as both a profitable electoral tactic and a religious wedge. In a stump speech in 2014, Modi told an audience in Assam that while Hindu migrants would be accommodated, other “infiltrators” would be sent back to Bangladesh. In April 2019, Amit Shah, now Modi’s home minister, said that Bangladeshi immigrants were “eating the grain that should go to the poor”. They were “termites”, Shah added. The BJP would pick them up, one by one, and “throw them into the Bay of Bengal”.

To get into the register, people had to prove first that an ancestor lived in Assam before 1971 and then that they were related to that ancestor. In a country of spotty electoral rolls and property deeds, of inconsistent name spellings and patchy documentation, this was always going to be difficult. When the registration of citizens began in 2015, Assam scrambled for its papers. Poor families, worried about being rendered stateless, spent their money on lawyers and documents. Some committed suicide. The so-called foreigners’ tribunals, set up to hear appeals, were incentivised to strike people off the register; the more foreigners you identified, the better your chances of staying on the tribunal.

In 2019, a Vice News examination of five of these tribunals found that nine out of 10 cases involved Muslims. Of the Muslims who appealed, 90% were declared illegal immigrants; for Hindus, the figure was 40%. The government plans to round up all these “foreigners” and transport them to fill nearly a dozen internment camps in the state. (One is already being built: a 28,000 sq metre, double-walled complex for 3,000 people, not far from the border with Bhutan. The centre has six watchtowers and a 100-metre-high light tower.) The BJP is so pleased with this process that it wants to compile a pan-Indian register of citizens, extending the exclusionary power of the process across a population of 1.3 billion.

India’s Narendra Modi addressing the BJP

campaign rally ahead of Delhi state elections

in New Delhi earlier this year.

Photograph: Manish Swarup/AP

Assam’s register was made public last August, and 1.9 million people, finding themselves omitted, had to hurry to file appeals. Four months later, the government passed the citizenship act. In this grand mechanism to determine “Indianness”, there will be one further component: a population register, hoovering up demographic data on the “usual residents” of India. But even this seemingly passive count of the population can transmute into yet another sieve for citizenship. After the population register is updated in September, lists of residents will be posted in each locality. Then anyone in the locality – officials, neighbours, vigilantes, RSS informers – can lodge an objection to your name’s inclusion. In such cases, you will be marked out as a “doubtful” citizen – a “D-voter” – with the prospect of being interned endlessly or thrown out of India. In this fug of paranoia, anyone might theoretically find themselves tagged “doubtful”: Muslims, dissidents, journalists and opposition political workers. The BJP knows its priorities. “No Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, Christian or Parsi,” a new BJP booklet assures readers, “will find their name in the D-voter list.” Muslims, again, are conspicuous by their absence.

The end game isn’t to rinse 180 million Muslims out of India. It can’t be, for practical reasons. Where would they go? Even those speculatively identified as illegal Bangladeshi immigrants cannot be sent back home unless Bangladesh accepts them. What the BJP is aiming for is what its founders have always wanted: a country that is Hindu before anything else. In the 1940s, both Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and Vinayak Savarkar, a leading RSS ideologue, were proponents of a two-nation theory. “The only difference,” says Niraja Jayal, a political scientist who studies Indian democracy, “was that Jinnah wanted the territory of undivided India to be cut into two, with one part for Muslims. Whereas Savarkar wanted Hindus and Muslims in the same land, but with the Muslim living in a subordinate position to the Hindu.” That unequal citizenship was what the RSS considered – and still considers – right and proper, Jayal said. “So you get a graded citizenship, a citizenship with hierarchies. You don’t need genocide, you don’t need ethnic cleansing. This does the job well enough.”

Modi’s first and second terms have now come to feel distinctly different. After 2014, the BJP consolidated its success by winning a series of state elections. The government began its citizenship registry in Assam, but its other prominent policies affected every Indian uniformly: a new tax on goods and services, chaotically implemented; a cancellation of high-value currency notes, intended to curb corruption but melting the economy down instead; and an Orwellian biometric identification scheme. The worst acts of rightwing violence – the beef lynchings – were committed by vigilantes emboldened by the BJP’s rise, and often supported by party leaders. (Two years ago, after eight convicted lynchers were released on bail, one of Modi’s ministers invited them to his house and draped floral garlands on them.) But the lynchings were not directly ascribable to the government in the way that events since Modi’s re-election last year have been.

In August 2019, three months into its second term, the government suspended a constitutional provision that has long granted special autonomies to the disputed border state of Jammu and Kashmir. Further, the state was split in two, and the halves brought under federal control. To forestall resistance, troops poured into the already heavily militarised Kashmir valley, and internet services across the state were shut down. They haven’t yet been properly restored; each passing day sets a new record for the longest shutdown of the internet by a government anywhere in the world. Kashmir’s leading opposition politicians were arrested; they haven’t been heard from since. Justifying a draconian detention order, the government argued that one of these politicians deserved to be held because of his ability “to convince his electorate to come out and vote in huge numbers”.

The RSS got the solution it wanted in Ayodhya as well. Since 1992, a legal battle has raged to determine what should be done with the site of the flattened mosque. In November, the supreme court – which appears increasingly pliant to the government’s needs – ruled that the mosque had been destroyed illegally, but that the land should nevertheless host a temple. It was as if a burglar, having been dressed down, was then invited to move into the house he’d robbed. The citizenship act was passed in December. Within half a year, with a speed and brazenness that left India dazed, the government had fulfilled some of the chief items on the RSS wishlist.

Assam’s register was made public last August, and 1.9 million people, finding themselves omitted, had to hurry to file appeals. Four months later, the government passed the citizenship act. In this grand mechanism to determine “Indianness”, there will be one further component: a population register, hoovering up demographic data on the “usual residents” of India. But even this seemingly passive count of the population can transmute into yet another sieve for citizenship. After the population register is updated in September, lists of residents will be posted in each locality. Then anyone in the locality – officials, neighbours, vigilantes, RSS informers – can lodge an objection to your name’s inclusion. In such cases, you will be marked out as a “doubtful” citizen – a “D-voter” – with the prospect of being interned endlessly or thrown out of India. In this fug of paranoia, anyone might theoretically find themselves tagged “doubtful”: Muslims, dissidents, journalists and opposition political workers. The BJP knows its priorities. “No Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, Christian or Parsi,” a new BJP booklet assures readers, “will find their name in the D-voter list.” Muslims, again, are conspicuous by their absence.

The end game isn’t to rinse 180 million Muslims out of India. It can’t be, for practical reasons. Where would they go? Even those speculatively identified as illegal Bangladeshi immigrants cannot be sent back home unless Bangladesh accepts them. What the BJP is aiming for is what its founders have always wanted: a country that is Hindu before anything else. In the 1940s, both Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and Vinayak Savarkar, a leading RSS ideologue, were proponents of a two-nation theory. “The only difference,” says Niraja Jayal, a political scientist who studies Indian democracy, “was that Jinnah wanted the territory of undivided India to be cut into two, with one part for Muslims. Whereas Savarkar wanted Hindus and Muslims in the same land, but with the Muslim living in a subordinate position to the Hindu.” That unequal citizenship was what the RSS considered – and still considers – right and proper, Jayal said. “So you get a graded citizenship, a citizenship with hierarchies. You don’t need genocide, you don’t need ethnic cleansing. This does the job well enough.”

Modi’s first and second terms have now come to feel distinctly different. After 2014, the BJP consolidated its success by winning a series of state elections. The government began its citizenship registry in Assam, but its other prominent policies affected every Indian uniformly: a new tax on goods and services, chaotically implemented; a cancellation of high-value currency notes, intended to curb corruption but melting the economy down instead; and an Orwellian biometric identification scheme. The worst acts of rightwing violence – the beef lynchings – were committed by vigilantes emboldened by the BJP’s rise, and often supported by party leaders. (Two years ago, after eight convicted lynchers were released on bail, one of Modi’s ministers invited them to his house and draped floral garlands on them.) But the lynchings were not directly ascribable to the government in the way that events since Modi’s re-election last year have been.

In August 2019, three months into its second term, the government suspended a constitutional provision that has long granted special autonomies to the disputed border state of Jammu and Kashmir. Further, the state was split in two, and the halves brought under federal control. To forestall resistance, troops poured into the already heavily militarised Kashmir valley, and internet services across the state were shut down. They haven’t yet been properly restored; each passing day sets a new record for the longest shutdown of the internet by a government anywhere in the world. Kashmir’s leading opposition politicians were arrested; they haven’t been heard from since. Justifying a draconian detention order, the government argued that one of these politicians deserved to be held because of his ability “to convince his electorate to come out and vote in huge numbers”.

The RSS got the solution it wanted in Ayodhya as well. Since 1992, a legal battle has raged to determine what should be done with the site of the flattened mosque. In November, the supreme court – which appears increasingly pliant to the government’s needs – ruled that the mosque had been destroyed illegally, but that the land should nevertheless host a temple. It was as if a burglar, having been dressed down, was then invited to move into the house he’d robbed. The citizenship act was passed in December. Within half a year, with a speed and brazenness that left India dazed, the government had fulfilled some of the chief items on the RSS wishlist.

Photograph: Indranil Mukherjee/AFP via Getty

Given the ferocity and stamina of the anti-government protests since December, it seems bewildering that no similar mobilisations met any of the government’s previous moves. From the 2019 election onwards, for several months, it seemed as if most Indians were implicitly in favour of this galloping onset of Hindutva. Why was it the citizenship act that electrified the public into protest? It may have partly been “the straw that broke the camel’s back”, Jayal said, but it also induced a broader, more primal kind of insecurity.

“With Kashmir, large segments of India have been persuaded over time that it’s a troubled region – which is an unfair stereotype, but maybe that made it harder for people to respond to its change in status,” she said. “With the Babri Masjid, it was fatigue over an issue that has dragged on for decades.” The citizenship act, though, “promises a whole range of unpleasant possibilities”. Despite the government’s assurances to Hindus and other non-Muslims, “everyone is anxious to be told they have to search for papers, although of course it’s worse for Muslims”, she said. “There’s the prospect of harassment. There’s the fear of being declared illegal. There’s the fear of the unknown.”

This sense of personal peril is matched by a sense of national peril. India can appear to be inured to injustices – the miscarriages of law, the iniquities of wealth and caste, the venality, the wounds and bruises to the body politic. What it still resists is any attempt to claw into the body and rearrange its very bones – its constitution. Nehru, Ambedkar and the other framers of India’s constitution engineered the country to be a liberal, secular democracy. Until recently, that idea had come to seem so impossible to dislodge that even patently unsecular politicians feel compelled to pay lip service to it. “Secularism is an article of faith for us,” Modi said during his 2014 campaign. By then, as an RSS member, he’d already been committed to the concept of a Hindu nation for 43 years.

'We are not safe': India's Muslims tell of wave of police brutality

When governments have threatened to split away from this constitutional foundation, they’ve met widespread popular opposition. After the prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended civic freedoms – of speech, of assembly, of due process – in 1975, she had to suppress waves of protest for the next 18 months, until she called off her declared state of emergency. The recent agitations against the citizenship act are similar: defiance of a law that meddles with the fundamental design of India.

For the first time since 1947, when the subcontinent went through its bloody partition into India and Pakistan, a politics is being constructed entirely around the premise of exclusion – of deciding who can’t be Indian, or calibrating how Indian anyone can be. The rabid focus on identity is a piece of a global pattern, of course, but it is especially dangerous in a country that is as tenuous a construct as India. This is still, as it was in 1947, a land teeming with so many identities – plotted multi-dimensionally along the axes of caste, gender, class, religion, language and ethnicity – that the only way to make it work is to accept that everyone belongs equally to India.

This egalitarian principle, therefore, has not been just an ideal; it has been a compact necessary for India’s survival. When a government starts to make the case for some to be considered less Indian than others, subtracting first one identity and then another as if they were Jenga blocks, the structure turns unsteady. Either the union dissolves, or it is kept together only by an iron-fisted, authoritarian regime – the kind that unleashes violence through the police, as in Uttar Pradesh, or through party auxiliaries under police protection, as at JNU. The danger posed by the BJP is that it is both preparing itself to be that regime and guiding India into an instability from which it may never recover.

Given the ferocity and stamina of the anti-government protests since December, it seems bewildering that no similar mobilisations met any of the government’s previous moves. From the 2019 election onwards, for several months, it seemed as if most Indians were implicitly in favour of this galloping onset of Hindutva. Why was it the citizenship act that electrified the public into protest? It may have partly been “the straw that broke the camel’s back”, Jayal said, but it also induced a broader, more primal kind of insecurity.

“With Kashmir, large segments of India have been persuaded over time that it’s a troubled region – which is an unfair stereotype, but maybe that made it harder for people to respond to its change in status,” she said. “With the Babri Masjid, it was fatigue over an issue that has dragged on for decades.” The citizenship act, though, “promises a whole range of unpleasant possibilities”. Despite the government’s assurances to Hindus and other non-Muslims, “everyone is anxious to be told they have to search for papers, although of course it’s worse for Muslims”, she said. “There’s the prospect of harassment. There’s the fear of being declared illegal. There’s the fear of the unknown.”

This sense of personal peril is matched by a sense of national peril. India can appear to be inured to injustices – the miscarriages of law, the iniquities of wealth and caste, the venality, the wounds and bruises to the body politic. What it still resists is any attempt to claw into the body and rearrange its very bones – its constitution. Nehru, Ambedkar and the other framers of India’s constitution engineered the country to be a liberal, secular democracy. Until recently, that idea had come to seem so impossible to dislodge that even patently unsecular politicians feel compelled to pay lip service to it. “Secularism is an article of faith for us,” Modi said during his 2014 campaign. By then, as an RSS member, he’d already been committed to the concept of a Hindu nation for 43 years.

'We are not safe': India's Muslims tell of wave of police brutality

When governments have threatened to split away from this constitutional foundation, they’ve met widespread popular opposition. After the prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended civic freedoms – of speech, of assembly, of due process – in 1975, she had to suppress waves of protest for the next 18 months, until she called off her declared state of emergency. The recent agitations against the citizenship act are similar: defiance of a law that meddles with the fundamental design of India.

For the first time since 1947, when the subcontinent went through its bloody partition into India and Pakistan, a politics is being constructed entirely around the premise of exclusion – of deciding who can’t be Indian, or calibrating how Indian anyone can be. The rabid focus on identity is a piece of a global pattern, of course, but it is especially dangerous in a country that is as tenuous a construct as India. This is still, as it was in 1947, a land teeming with so many identities – plotted multi-dimensionally along the axes of caste, gender, class, religion, language and ethnicity – that the only way to make it work is to accept that everyone belongs equally to India.

This egalitarian principle, therefore, has not been just an ideal; it has been a compact necessary for India’s survival. When a government starts to make the case for some to be considered less Indian than others, subtracting first one identity and then another as if they were Jenga blocks, the structure turns unsteady. Either the union dissolves, or it is kept together only by an iron-fisted, authoritarian regime – the kind that unleashes violence through the police, as in Uttar Pradesh, or through party auxiliaries under police protection, as at JNU. The danger posed by the BJP is that it is both preparing itself to be that regime and guiding India into an instability from which it may never recover.

IS FASCISM, CASTISM AND RACISM

No comments:

Post a Comment