Many American chess enthusiasts regard FM Alisa Melekhina as one of the strongest female players in the United States. Melekhina has participated in eight different U.S. Women's Championships and has represented the country abroad in two different Women's World Team Championships.

While the 28-year-old has achieved a myriad of accomplishments in the chess world, she has been extremely successful off the board as well. While she was at the peak of her chess career, she was pursuing a J.D. (Doctor of Law) at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Today, Melekhina works as an attorney for a large corporate law firm practicing white-collar, commercial, and intellectual property litigation.

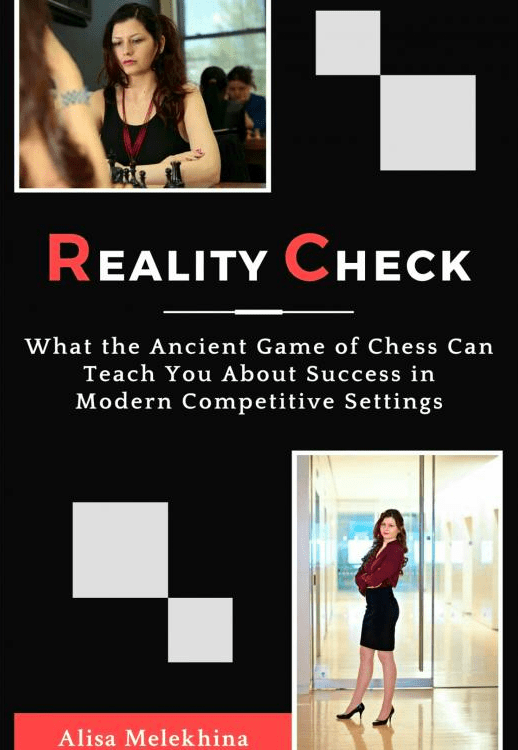

Since becoming a full-time attorney, Melekhina has been outspoken about how chess has helped her professional development. She even wrote the book Reality Check: What the Ancient Game of Chess Can Teach You About Success in Modern Competitive Settings in 2017, discussing the crossover between chess and the modern workplace.

Currently, Melekhina runs the New York City Corporate Chess League (NYCCL), a corporate chess league which she founded, featuring teams from esteemed companies like Google, Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, and Debevoise & Plimpton LLP. The NYCCL finished its second season last November and features a healthy mix of titled and untitled players.

Chess.com: Can you tell us about what made you choose a career as an attorney? Did chess play a role in influencing your decision?

Alisa Melekhina: Law seemed like the natural career option when considering my varied interests. When I was young, I was always intellectually curious and enjoyed puzzle-solving and detective stories. During my high school years, I focused more on science but renewed my interest in writing and logic upon studying philosophy. From there, law was the natural progression given that it draws on essential skills for analytical thinking and persuasive reasoning.

Unsurprisingly, these are also skills prevalent in chess. The skill of planning and anticipating an adversary’s response especially overlap in both fields. Thus, I do credit chess as influencing my decision. On a practical level, at the time I was considering law school, I was also intrigued by the various intellectual property issues present in chess (for example, copyrights over games or player images) and was excited to study this field in law.

How did balancing chess and your academic career help you grow (in both pursuits)? Did you have any setbacks along the way?

I went straight to law school after graduating with my bachelor’s degree in philosophy (summa cum laude) in two years in 2011. I graduated from Penn Law in 2014. Indeed, during this time I was very active in chess and achieved several chess career highlights. Those who were aware of my academic pursuits might have underestimated how seriously I could still compete in chess. However, that inspired me even more because I thought I had to “prove myself” in being able to succeed in both fields

How did balancing chess and your academic career help you grow (in both pursuits)? Did you have any setbacks along the way?

I went straight to law school after graduating with my bachelor’s degree in philosophy (summa cum laude) in two years in 2011. I graduated from Penn Law in 2014. Indeed, during this time I was very active in chess and achieved several chess career highlights. Those who were aware of my academic pursuits might have underestimated how seriously I could still compete in chess. However, that inspired me even more because I thought I had to “prove myself” in being able to succeed in both fields

However, my chess play was very volatile during this time, and I had as many “downs” as “ups.” It is easy to blame the setbacks on lack of time. Yet, I found that time was not the culprit. It was the lack of prioritization on my part and seeking “escapes” in one field when the other wasn’t going well. For example, if I had a lamentable tournament, I would bury myself in my law casebooks the next day and forget about the tournament (at the exclusion of taking the time to analyze and learn from my games). Conversely, if I had a setback with law applications, I would refocus on chess and enter an all-consuming, long tournament. This created a toxic cycle.

To exit, I ultimately had to decide what I wanted to prioritize, and importantly, why. I explored this dilemma in one of my debut articles for the United States Chess Federation's Chess Life Online (“Legal Moves: Melekhina on Chess & Law School”) in 2014, which turned out to resonate with many readers and has inspired my subsequent chess journalism.

Looking back, do you think chess has helped your professional growth? How might it help others who have a career outside of law?

Chess 100 percent contributed to my professional growth. Coming from an immigrant family and being a first-generation lawyer, I was coming into the corporate world with a blank slate. Especially for a field that depends as much on networking as it does on academic excellence, I had limited resources to consult and had to figure out everything —from law school admissions to internships, to the job application process — on my own.

Chess 100 percent contributed to my professional growth. Coming from an immigrant family and being a first-generation lawyer, I was coming into the corporate world with a blank slate. Especially for a field that depends as much on networking as it does on academic excellence, I had limited resources to consult and had to figure out everything —from law school admissions to internships, to the job application process — on my own.

Chess 100 percent contributed to my professional growth.—Alisa Melekhina

I credit chess for the strategic and planning skills required to navigate this process. All job candidates have different strengths, and chess equipped me with a unique skill set that helped put me at least on a level playing field with colleagues much older and with more distinguished pedigrees than I had.

In 2017, you wrote and published your book, which discusses why you believe chess helps navigate the modern workplace. What inspired you to write this book?

The book is a collection of my thoughts and introspection on the connections between chess and other competitive fields. Its incipiency was my early writings on chess.

The book is a collection of my thoughts and introspection on the connections between chess and other competitive fields. Its incipiency was my early writings on chess.

The book adopts a meta-perspective on the motivations behind chess, the mindset required to succeed—whatever that means, a concept also discussed—and what we can glean from those lessons as applied to the external world.

In your book, you write:

"Rather than reacting to every obstacle or dashed expectation, incorporate the event into your overall plan. Real-life setbacks like rejections, broken promises, and unfair disadvantages will happen. Rethink the meaning behind the emotional triggers and how your reaction will further your purpose. Manage emotions by recognizing their place, but do not allow them to control your moves."

Can you give an example of how managing your emotions and decision-making process at the board has translated into your day-to-day responsibilities as an attorney?

The day-to-day of an attorney includes —if not already working on meeting a tight deadline—requests for immediate responses from clients or senior team members. When first assimilating to such a demanding work environment, the intuitive reaction is to crank out a hurried response. Chess, on the other hand, teaches you to stay calm in the face of pressure and competing demands.

The day-to-day of an attorney includes —if not already working on meeting a tight deadline—requests for immediate responses from clients or senior team members. When first assimilating to such a demanding work environment, the intuitive reaction is to crank out a hurried response. Chess, on the other hand, teaches you to stay calm in the face of pressure and competing demands.

I’d like to think that chess reinforces a default setting where I’ll first contemplate the best way to approach a demanding situation from all angles of substance and timing, rather than making an impulsive reaction.

Your experience as both a top chess player and a successful attorney is unique in that both fields are traditionally dominated by men. What advice would you offer young women looking to follow in your footsteps? What were some obstacles you had to overcome to get to where you are now?

Indeed, the chess and law fields share many parallels concerning overall female participation and retention in more senior roles. Similar to scholastic levels in chess, the starting law school and firm associate classes tend to be evenly split among men and women. When considering ascension into senior roles such as partnership, however, the numbers begin to dwindle. Last I checked the stats, the number of female equity partners at law firms was less than 20 percent. In chess, I believe women comprise about less than three percent of all national masters and less than two percent of grandmasters worldwide.

Your experience as both a top chess player and a successful attorney is unique in that both fields are traditionally dominated by men. What advice would you offer young women looking to follow in your footsteps? What were some obstacles you had to overcome to get to where you are now?

Indeed, the chess and law fields share many parallels concerning overall female participation and retention in more senior roles. Similar to scholastic levels in chess, the starting law school and firm associate classes tend to be evenly split among men and women. When considering ascension into senior roles such as partnership, however, the numbers begin to dwindle. Last I checked the stats, the number of female equity partners at law firms was less than 20 percent. In chess, I believe women comprise about less than three percent of all national masters and less than two percent of grandmasters worldwide.

Because I grew up playing in mixed open tournaments since the age of seven, when I regularly won against men eight to 10 times my age, I was never even cognizant of gender disparities until I got older. Chess is an opportunity to resolve all battles over the board, regardless of age, gender, or background. It is an excellent tool for instilling confidence, in all kids, to level with adults, precisely because the moves speak for themselves.

In corporate settings, on the other hand, information is not as transparent as a recording of chess moves. Implicit biases based on gender and youth are significantly more difficult to overcome because the “results” are not as definitive and there is no inherent “rating” that you can rely on as an indication of your strength.

Chess is an opportunity to resolve all battles over the board, regardless of age, gender, or background.—Alisa Melekhina

Chess reinforces self-reliance, and likewise in the real world, you have to be your number one biggest advocate. Regardless of the setting, don’t ever be shy about speaking up to either offer your opinions or else vouch for yourself. (Because if you don’t, it’s not likely that someone else will).

What inspired you to run the New York City Corporate Chess League? What does the league's popularity say about how these companies view chess as an asset for potential incoming talent?

I am very pleased with the success of the NYCCL to date. It initially formed as the natural next step in finding a common forum for myself and my friends—all longtime chess players who found themselves at major NYC financial/business institutions. We all came across other chess enthusiasts at our respective companies but needed a formal outlet to share our common interest.

I am very pleased with the success of the NYCCL to date. It initially formed as the natural next step in finding a common forum for myself and my friends—all longtime chess players who found themselves at major NYC financial/business institutions. We all came across other chess enthusiasts at our respective companies but needed a formal outlet to share our common interest.

As you mentioned and as I discussed recently on the Ladies Knight podcast with WGM Jennifer Shahade, the NYCCL facilitates play among corporate professionals of all skill and seniority levels. It’s not that the league led to its popularity; rather, the league came to be because of the existing popularity of chess among various players at these large institutions.

Because of how large the participating banks and companies are, it is impossible for a particular person to know everyone within the company. The league offers a medium for reaching out to chess players in any role within the company in order to represent the company as a collective team. Thus, the NYCCL arose primarily as a way to harness and organize that existing shared interest. For example, it created a sustained network among otherwise decentralized information.

I am most proud that the league accomplishes the goal by providing a forum for chess players of all skill and seniority levels to compete. It’s a way to look past the traditional corporate hierarchies and bring people together within companies and among the external teams. The common factor is that chess is highly respected, and a setting such as the NYCCL helps elevate the status of chess as a mainstay in corporate culture. Our goal is for this sentiment to spread, which would then organically inform staffing or hiring considerations down the line.

For novice players interested in learning chess to boost their professional development, what advice would you offer? Does one have to become master-strength to grow?

The goals in learning chess differ depending on whether you decide to play to be competitive, as a scholastic extra-curricular, or as a working professional. In the latter category, the greatest takeaways that chess can offer, in my opinion, are skills enhancing sustained focus, patience, and organization.

The goals in learning chess differ depending on whether you decide to play to be competitive, as a scholastic extra-curricular, or as a working professional. In the latter category, the greatest takeaways that chess can offer, in my opinion, are skills enhancing sustained focus, patience, and organization.

It is certainly not necessary to be master-level to appreciate these aspects. However, it is important to keep in mind that progressing in chess requires more than just playing online. I meet many working professionals whose experience in chess is limited to playing quick, online games. That will only take you so far, and in fact, will become detrimental to your overall growth because it will reinforce bad habits. If you are considering playing chess on an adequate level to compete among colleagues, you have to be prepared to budget in time for studying in addition to playing. It doesn’t have to be a major time commitment so long as when you do focus on chess, you are focusing on the right things.

Of all the games you've played, which is your favorite?

I’m most proud of my win over Alexander Shabalov because I figured out a new move order over the board, and had numerous successes with this line of the Alapin opening later in my chess career:

No comments:

Post a Comment